This is the last of four briefs in The Commonwealth Fund’s Medicare at 50 Years series that explore the key issues confronting the Medicare program and policy options for addressing them. The first brief discussed the potential of value-based payment to improve beneficiary care and achieve savings; the second outlined policy options for modernizing Medicare’s benefits and limiting costs for low-income beneficiaries; and the third assessed how projections of future program costs have changed since 2000 and how legislative reforms have affected the sources and levels of Medicare financing.

The Commonwealth Fund’s Medicare at 50 Years series is now available in its entirety for viewing and download as an e-book.

Abstract

Medicare was originally designed to protect beneficiaries from the financial burden of acute episodes of illness. As lifespans lengthen, Medicare must adapt to serve beneficiaries with substantial long-term physical or cognitive impairment who need personal care assistance. These beneficiaries often incur high out-of-pocket costs for Medicare-covered services as well as home and community care not covered by Medicare. This latter category of care is often key to continued independence. To improve Medicare’s capacity to serve such beneficiaries, and to prevent unnecessary institutionalization, this issue brief, one in a series on Medicare’s future challenges, proposes a complex care benefit option that would include home and community services, and describes how it might be structured to balance the goals of improving care for beneficiaries and ensuring affordability.

Background

Analysts of the Medicare program have long noted that it does a poor job serving those with multiple chronic illnesses. Most conspicuous is its lack of coverage for home- and community-based services, which enable seniors with complex conditions to live independently.

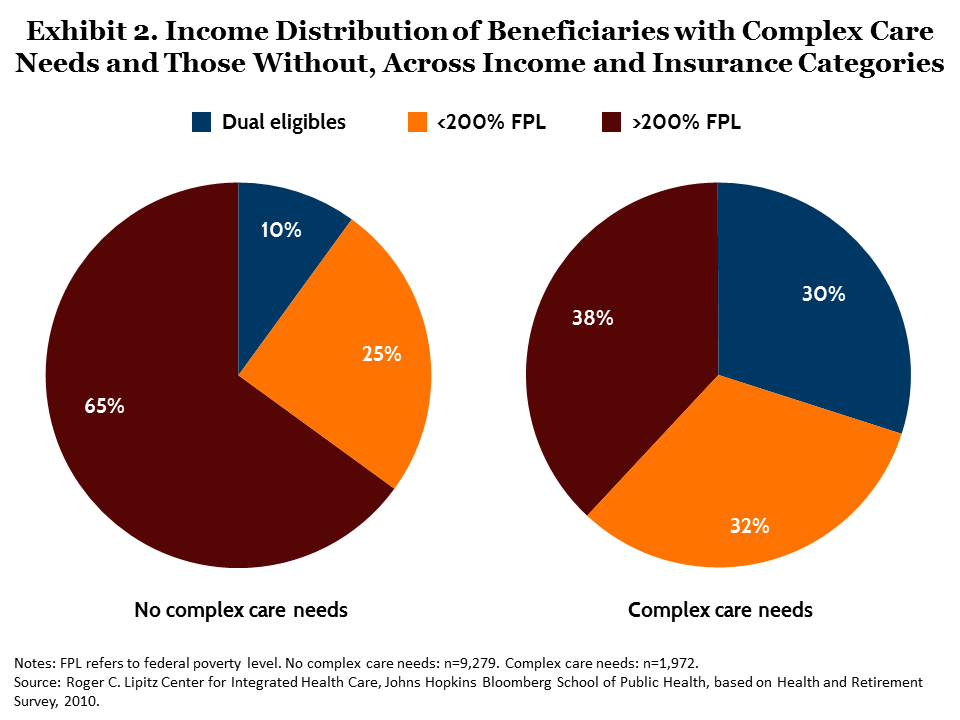

While home- and community-based services are covered through state Medicaid programs, less than a third of Medicare beneficiaries with complex care needs are covered by Medicaid (the so-called dual eligibles). Low- and modest-income Medicare beneficiaries not covered by Medicaid face significant obstacles—financial and otherwise—to obtaining these services. Even beneficiaries who can afford to pay out of pocket for noncovered services can find it challenging to identify reliable, competent personal care providers. Physicians, nurses, and other traditional health care providers often cannot make knowledgeable recommendations about community services, such as senior day care centers, support for caregivers, or other personal care providers. This can even be true for individuals in Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plans (Medicare managed care plans that cover dual eligibles and facilitate coordination with Medicaid benefits), unless the contracting entity offers its enrollees a highly coordinated program.

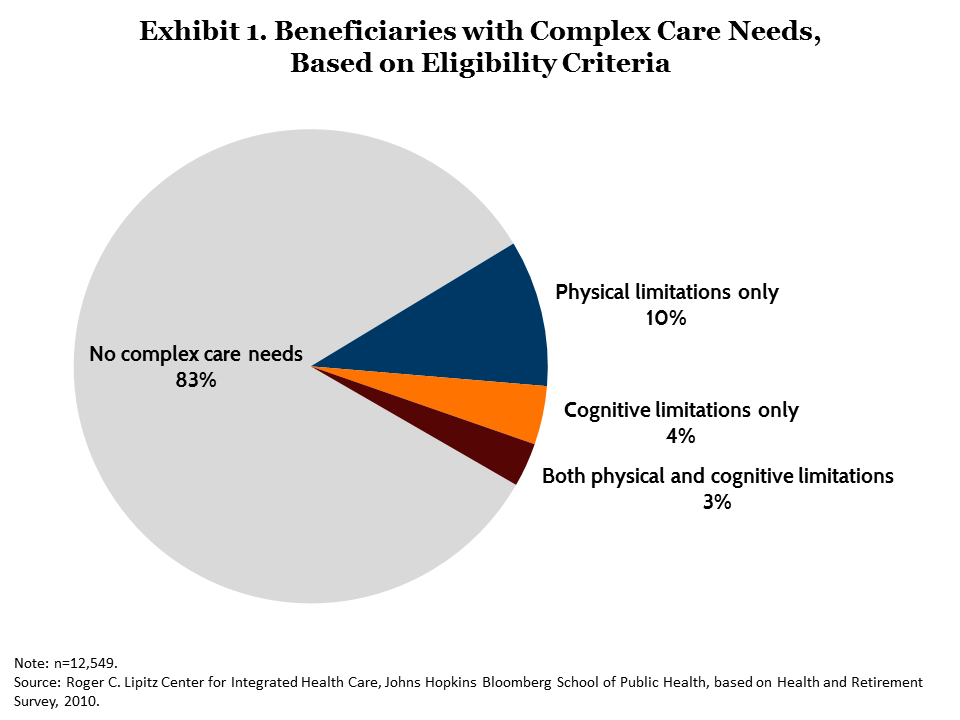

Medicare has tried an array of approaches to delivering care more effectively to high-risk Medicare beneficiaries, with mixed results. Although the proportion of beneficiaries requiring complex care for multiple conditions is relatively small—an estimated 17 percent—care provided to this group accounts for 32 percent of Medicare spending on noninstitutionalized beneficiaries. Figuring out how to improve benefits for this population could have a positive impact on the entire Medicare program and on overall costs.

A new complex care benefit option for Medicare beneficiaries could improve patient and caregiver experience, help beneficiaries continue living at home, and reduce burdens on families who now try to patch together the resources needed to pay for care. One challenge is how to design a payment structure for a broader set of services that appropriately rewards providers of home and community care, thus helping to spread successful models of care more broadly.1

This issue brief describes the characteristics and needs of Medicare beneficiaries who require complex care, the goals of a new benefit option that could be made available to this population, and a proposed structure that would both improve care and achieve savings.

Complex Beneficiaries and Their Needs

Medicare beneficiaries meet our definition of “complex care beneficiaries” if they live at home or in the community, are not long-term residents of an institution such as a nursing, residential care, or assisted living facility, and have one or both of the following characteristics:

- Significant impairment in physical functioning—some difficulty with two or more activities of daily living, such as eating or bathing.

- Severe impairment in cognitive functioning (based on a summary cognitive impairment score covering immediate and delayed word recall, counting, naming, and vocabulary tasks), a self-reported diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or dementia, or the inability to complete the Health and Retirement Survey Questionnaire because of poor comprehension.

About 9 million Medicare beneficiaries meet this definition (Exhibit 1), of which 30 percent are eligible for Medicaid and about 32 percent are living below 200 percent of the federal poverty level but not covered by Medicaid (Exhibit 2).2 This latter group is most at risk for being unable to pay for home and community services directly out-of-pocket, exhausting their limited savings, and entering a nursing home. where they can qualify for Medicaid after a short period.

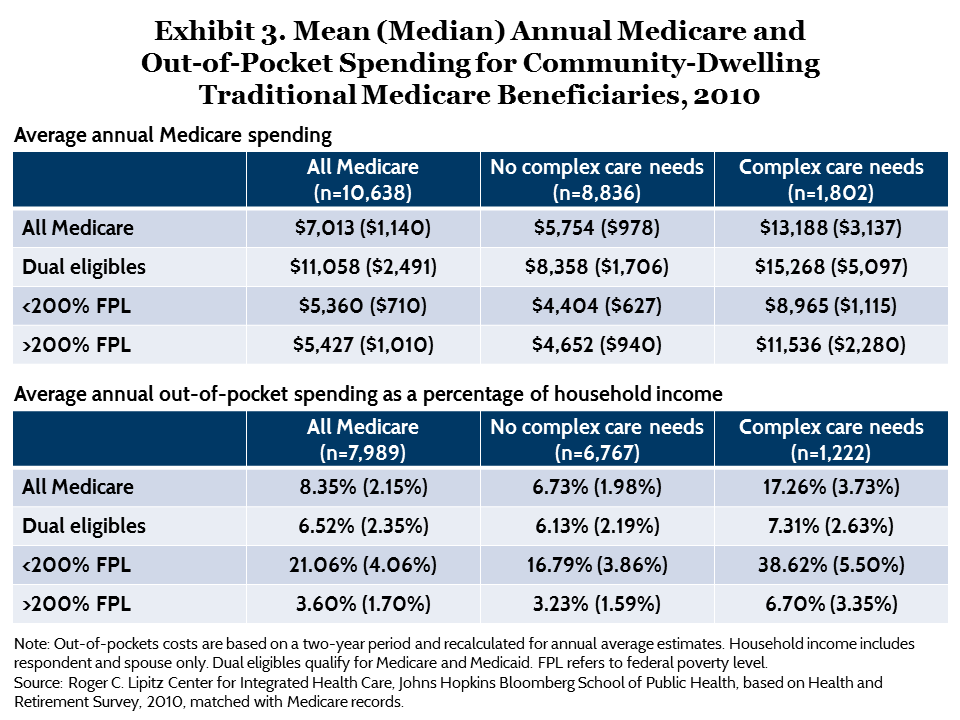

In 2010, Medicare’s mean payment for complex-needs beneficiaries was $13,188, compared with the mean payment of $5,754 for noncomplex beneficiaries (Exhibit 3). Out-of-pocket spending was also higher for the complex-needs group, with average annual spending at 17 percent of their income versus 7 percent for beneficiaries without complex needs. The spending gap between the two groups widens among beneficiaries who live below 200 percent of the federal poverty level but do not qualify for Medicaid.

Why More Comprehensive Benefits Are Needed for Complex Care

Medicare provides better coverage (with less cost-sharing) for higher levels of care, and more restricted coverage for lower levels of care such as skilled nursing or outpatient therapy (which are subject to relatively low, arbitrary limits) and home health care (for which patients must meet criteria such as being homebound and requiring care of skilled nurses). In addition, some social services that might be essential for patient care, quality of patient experiences, and independent functioning are not covered by Medicare if they are not deemed medical in nature and intended to meet acute care needs.

Medicare does not provide an opportunity to substitute home and community care for more costly medical care, nor does it support models of delivery that employ both home care and acute care, such as the Hospital at Home model of care.3 Consequently, the handoff from one setting (such as a hospital) to another (like home health) is awkward at best. Medical records do not follow the patient between settings, so needs assessments must be repeated in each setting. In addition, professionals in one setting are generally poorly informed about care plans in the next round of care. The patient and his or her caregiver face a bewildering array of choices at a time when the pressures of a health crisis can reduce the ability to make good decisions.

Given these realities, there is a threefold rationale for providing home and community care services such as personal care, senior day care, and caregiver training and support to a targeted group of beneficiaries with complex care needs:

- The cost of such services represents a major financial burden on beneficiaries with modest incomes.

- Without better support in the home, complex beneficiaries are more likely to require long-term institutional care, eventually qualifying for Medicaid and increasing long-run federal and state Medicaid expenditures.

- Even higher-income individuals often lack information about and assistance with obtaining high-quality, coordinated home and community services that are tailored to fit their needs and circumstances; such individuals could benefit from a new complex-care benefit even if they must pay the full actuarial cost.

The Long-Term Care Commission and numerous research studies have confirmed these observations.4 Moreover, the U.S. lags other countries in addressing the issue. Denmark, for example, made a major commitment to home care and preventing nursing home placement in 1987, leading to a major shift in long-term care expenditures away from institutional care.5 The Canadian province of Ontario just launched a major expansion of home care.6 And the Dutch have implemented innovative models of self-directed nursing care for home care residents that include both skilled nursing care and personal care services.7

Previous Efforts to Improve Complex Care

The needs of this vulnerable population are broad, and so is the range of approaches to meeting those needs. Past efforts have generally shared two primary goals: 1) to prevent or delay admission to a nursing home by improving care provided in the home or community, and 2) to improve coordination across acute and long-term care needs.8 Two major obstacles currently challenge these goals. One is the difficulty of paying for and coordinating nonmedical services and personnel.9 The other is the lack of financial incentives for all those participating to reduce use of services, including long-term nursing home care.

Past demonstration projects, such as Care Management for High-Cost Beneficiaries and the Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration (MCCD), have focused on specific chronic conditions, disease management, and care coordination rather than on functional and cognitive limitations and in-home services.10 In fact, MCCD specifically excluded people with cognitive limitations. The same holds for states participating in the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ State Innovation Models (SIM) initiative.11 While the Arkansas SIM program does target Medicaid beneficiaries with complex needs, it is designed to provide performance-based payments tied to the level of care coordination achieved. The Oregon model, meanwhile, creates “coordinated care organizations” to assist those with complex conditions.

Envisioning a New Complex Care Need Benefit

Our approach to a complex care benefit is guided by the fact that most older adults with complex care needs have significant out-of-pocket costs for essential noncovered services and are often at risk of institutional placement. As envisioned, the benefit would target beneficiaries with physical or cognitive impairment or those who experience serious difficulty navigating multiple sources of acute care and social services.

Coordinate Complex Care. A new entity, which we call a complex care organization (CCO), would form the backbone of the new complex care benefit. Similar to accountable care organizations (ACOs), CCOs would have a strong primary care foundation. They would:

- deliver a comprehensive range of health care services, including in-home care;

- develop individualized care plans in consultation with each beneficiary;

- provide care management services;

- coordinate all care patients receive; and

- ensure that care is both appropriate and of high quality.

As with ACOs, participating providers would be eligible for a share of the health care savings generated from the expected reduction in nursing home placements. CCOs also would be eligible to receive the new chronic care coordination fees that Medicare began offering to primary care providers in January 2015.12

In addition, financial support would be made available to caregivers, whether they are family members or friends—who provide the lion’s share of personal services for patients at home—or hired professionals. While family and friends are likely to be preferred by the patient in most instances, many beneficiaries will not have access to a network of family caregivers. Further, caregiver burnout is a well-established phenomenon; at some point, paid support is likely to be needed to relieve the burden on family caregivers.

Cover Nonmedical Services That Support Independence. Additional nonmedical services would be offered to support independent living, including personal care assistance and respite care. Services such as meal support, medication reminders, and interventions to evaluate and address safety in the home could reduce falls or medication mishaps that often lead to preventable hospital admissions and expensive follow-up care. In some states, these and similar services are already available to dual eligibles through Medicaid, but not to those who are not impoverished enough to be covered by Medicaid.

Ensure Flexibility. Medicare benefits are very prescriptive and involve myriad regulations and limitations. Although these are intended to prevent coverage abuses, they also can be barriers to needed care, at times doing more harm than good. To serve the needs of the complex-care population effectively, flexibility is essential. Therefore, in our approach benefits would be creatively bundled and tailored to specific needs.

Base Cost-Sharing on Income. Cost-sharing would be affordable and based on the ability to pay, with larger subsidies provided to beneficiaries with low and moderate incomes. Affordable cost-sharing is particularly important for those with modest incomes, whose resources may be too high to qualify for Medicaid but are insufficient to pay for the additional services that support independent living.

All of the above goals must be developed within a realistic context: A broad expansion of services even for the most needy of Medicare beneficiaries is likely not feasible in the current fiscal and political climate. A well-designed benefit with reasonable limits on spending for additional services, but with better coordination of care and more support for independent living, would lead to savings elsewhere in Medicare and Medicaid. As an example, the Maximizing Independence at Home model of care, which supports people with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, has reduced or delayed nursing home placement by an average of 110 days, yielding savings of $26,000 over three years.13

Of course, even a careful and frugal approach to improving services for beneficiaries could lead to higher costs. Policymakers need to be assured that these changes are well managed and not simply opening Medicare to substantial new costs. Requiring higher-income beneficiaries to finance most of the cost of their services through premiums or copayments, and setting affordable copayments for modest-income beneficiaries, would further limit government outlays.

Advantages and Vulnerabilities

One advantage of covering home and community care through the complex care organizations we envision is that CCOs could relax the sometime arbitrary rules that currently govern the providers of these services. In place of these rules, more meaningful quality standards, such as achieving patient satisfaction goals and demonstrating the effectiveness of their care, could be created. For example, by combining outpatient rehabilitation and home health rehabilitation service, CCOs might be able to meet patients’ needs better and eliminate some of the restrictions on providers of these services. What is not yet known is whether this would result in genuine cost savings—particularly to the extent that there are currently substantial unmet needs.

There is also the possibility that CCOs would have an incentive to skimp on care, or place undue burdens on family caregivers, if they were at risk for the full cost per person. One possible safeguard is to have the CCO share risk with Medicare, rather than bear full financial risk. Mandatory reporting on quality of care, including data on beneficiary and family caregiver experiences, also would help in this regard.

Another concern is that paid in-home care would substitute for family caregiving. But income-based cost-sharing would likely temper demand for in-home paid services. A reduced cash allowance also could be made available to families able and willing to directly provide services in lieu of formal paid in-home care.

Determining Eligibility and Expanding Services

Clear and carefully considered eligibility requirements are a necessity. Policymakers would need to decide which functional limitations would qualify, which in-home and community services are needed in combination with more traditional medical care to optimize independence and health, and under what conditions beneficiaries could move in and out of the benefit. For instance, a transient illness may require a temporary enrollment in the CCO.

Just as CMS is now implementing and monitoring the impact of ACOs, it also could undertake demonstrations of CCOs. These pilots would generate evidence on: which beneficiaries stand to gain the most from a complex care benefit; the qualifications an organization needs to serve as a CCO; the types of services that CCOs should offer; the benefit’s effects on quality of care and health outcomes; and cost impact.14

The structure of beneficiaries’ financial incentives must be carefully considered as well. Two goals must be balanced: helping beneficiaries avoid the devastating financial burdens that complex illness or frailty often bring about, and preventing excessive reliance on paid services. Incentives should be geared to maintaining beneficiaries in a home setting at an affordable cost. In determining who should qualify for benefits and what the level of benefits should be for beneficiaries in different situations, the role of caregivers must be addressed. Beneficiaries without a family support system are most likely to be at risk. But even when family members are available as caregivers, they should be supported in that role.

Conclusion

Cost, potential savings, financing, eligibility criteria, quality of care, and patient experience—these are some of the critical issues that must be explored and addressed to move forward with a Medicare complex care benefit. Accelerated testing of the CCO concept is important, however, and should begin soon. With more than 10,000 Americans turning 65 every day, the need for services to care for Medicare beneficiaries with complex needs will grow markedly over the coming decade. Devising affordable, high-quality programs that can allow these individuals to remain at home both raises overall quality of life and potentially reduces spending on institutional care. Each is a worthy goal; combined, they create a powerful incentive for progress.

Notes

1 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Chronic Care Management Services: CY 2015 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (Washington, D.C.: CMS, Feb. 18, 2015), http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/NPC/Downloads/2015-02-18-Chronic-Care-Presentation.pdf.

2 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare Enrollment—National Trends 1966–2013 (Washington, D.C.: CMS), https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/MedicareEnrpts/Downloads/SMI2013.pdf.

3 K. Davis, C. Buttorff, B. Leff, et al., “Innovative Care Models for High-Cost Medicare Beneficiaries: Delivery System and Payment Reform to Accelerate Adoption,” American Journal of Managed Care, 2015 21(5):71–78; B. Leff, L. Burton, S. L. Mader et al., “Hospital at Home: Feasibility and Outcomes of a Program to Provide Hospital-Level Care at Home for Acutely Ill Older Patients,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Dec. 2005 143(11):798–808; K. Davis, C. Buttorff, B. Leff et al, “For High-Risk Medicare Beneficiaries: Targeting CMMI Demonstrations on Promising Delivery Models,” Health Affairs Blog, April 22, 2014, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/04/22/for-high-risk-medicare-beneficiaries-targeting-cmmi-demonstrations-on-promising-delivery-models/.

4 Commission on Long-Term Care, Report to the Congress, Sept. 18, 2013; Alliance of Community Health Plans, Supporting Well-Being for an Aging Population, May 12, 2015, https://www.achp.org/resource/research/taking-better-care-supporting-well-being-for-an-aging-population/; A. Dodd and R. Malsberger, Home- and Community-Based Service Use Among Medicare-Medicaid Enrollees with Functional Limitations, 2007–2008, Medicaid Policy Brief no. 20 (Washington, D.C.: CMS, Sept. 2013), http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/Downloads/MAX_IB20_MCBS_HCBS.pdf.

5 N. K. Raffel and M. W. Raffel, “Elderly Care: Similarities and Solutions in Denmark and the United States,” Public Health Report, Sept.–Oct. 1987 102(5):494–500; G. W. Leeson, “Services for Supporting Family Carers of Elderly People in Europe: Characteristics, Coverage and Usage,” in Eurofamcare National Background Report for Denmark, July 2004.

6 Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Patients First: A Roadmap to Strengthen Home and Community Care, catalogue no. 020047 I, May 2015.

7 B. H. Gray, D. O. Sarnak, and J. S. Burgers, Home Care by Self-Governing Nursing Teams: The Netherlands’ Buurtzorg Model (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, May 2015).

8 C. Boult, A. F. Green, L. B. Boult et al., “Successful Models of Comprehensive Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s ‘Retooling for an Aging America’ Report,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Dec. 2009 57(12):2328–37; M. D. Fretwell, J. S. Old, K. Zwan et al., “The Elderhaus Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly in North Carolina: Improving Functional Outcomes and Reducing Cost of Care: Preliminary Data,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, March 2015 63(3):578–83.

9 Davis, Buttorff, Leff et al., “Innovative Care Models,” 2014.

10 R. Brown, D. Peikes, A. Chen et al., The Evaluation of Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration: Findings for the First Two Years (Washington, D.C.: CMS, March 21, 2007), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/Evaluation-of-Medicare-Coordinated-Care.pdf.

11 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, State Innovation Models Initiative: Model Test Awards Round One (Washington, D.C.: CMS), https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/State-Innovations/State-Innovation-Models-Initiative-Round-One-Frequently-Asked-Questions.html.

12 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Chronic Care Management Services, 2015; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: First Annual Report (Washington, D.C.: CMS, Jan. 2015), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/CPCI-EvalRpt1.pdf.

13 Q. M. Samus, D. Johnston, B. S. Black et al., “A Multidimensional Home-Based Care Coordination Intervention for Elders with Memory Disorders: The Maximizing Independence at Home (MIND) Pilot Randomized Trial,” American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, April 2014 22(4):398–414.

14 K. Davis, C. Buttorff, B. Leff et al., “For High-Risk Medicare Beneficiaries: Targeting CMMI Demonstrations on Promising Delivery Models,” Health Affairs Blog, April 22, 2014, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/04/22/for-high-risk-medicare-beneficiaries-targeting-cmmi-demonstrations-on-promising-delivery-models/.