|

by Deborah Lorber

What's perhaps most surprising, however, is that Richmond is a doctor, with her own private practice in Dayton, Ohio. She knew how important it was to keep her diabetes under control, and she had the income to allow her to do it, paying in cash for doctors' visits, labs, and medications. Still, Richmond lived in fear of the possibility of a car accident or serious illness. "I would have had insurmountable medical bills," she said. On the very first day coverage was available under the new law, Richmond went online to her state's marketplace and signed up. "I feel safer now," she said. "I went for so long walking a tight rope without a net."

Tanisha Richmond's experience mirrors those of millions of Americans and highlights just one of the problems with our country's health system prior to health reform: insurers' ability to discriminate against applicants with conditions like diabetes—and heart disease, cancer, and depression. It is because of this inequity and many others that Congress passed the Affordable Care Act, also known as the ACA or Obamacare, in March 2010. On this fifth anniversary of the law, we look back to its original goals, acknowledge its accomplishments and challenges, and turn toward its future.

Why Do We Need Health Reform?

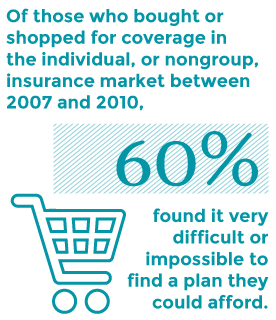

In addition to the millions who could not get health insurance because of preexisting medical conditions, millions more simply could not afford it. For working-age Americans who had to shop for insurance on their own—because they weren't offered or eligible for employer health benefits or didn't qualify for Medicaid or other public coverage—premiums were often steep. Of those who bought or shopped for coverage in the individual, or nongroup, insurance market between 2007 and 2010, 60 percent, or 16 million people, said they found it very difficult or impossible to find a plan they could afford. When people did find a health plan, often they found their premiums went up and up year after year—10 percent or more per year during the three years before the ACA went into effect. People who lost their jobs and their employer-sponsored health plans could find themselves and their entire families an illness or accident away from financial crisis.

Even with health insurance, many Americans found that certain services, like maternity care, were excluded from their policy, or that they lacked adequate protection from costs. There were annual and lifetime dollar limits on care and plans without prescription drug benefits. In some cases, people had their policies rescinded, or cancelled, because they had illnesses that required expensive treatments.

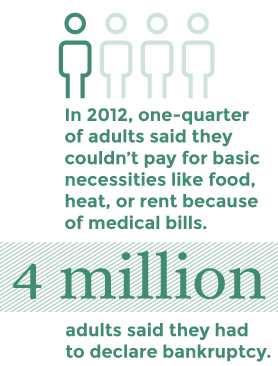

Having poor insurance coverage, or going without health insurance altogether, has financial and health consequences. In 2012, one-quarter of adults said they couldn't pay for basic necessities like food, heat, or rent because of medical bills. Four million adults said they had to declare bankruptcy. In addition, people were increasingly going without needed care because of cost.

Finally, as a country we were, and still are, devoting an astonishing amount of our total spending to health care. In 2009, the U.S. spent nearly $8,000 per person on health care, far more than other high-income nations—even though Americans aren't any healthier as a result.

Enter the Affordable Care Act

The primary goals of the ACA are pretty simple: enable many more people to gain access to affordable health care coverage and make sure that coverage pays for the kind of health services everyone needs, from preventive care to mental health services. Its reforms are also intended to prevent insurers from turning down people like Tanisha Richmond for health reasons, or from charging them more or dropping them from policies. Now, insurers must charge people the same premiums, with limited exceptions based on your age, where you live, and whether you use tobacco.

The ACA helps people get coverage in a few ways. First, it allows young adults to stay on a parent's health plan until age 26 if their parents' employers and insurers offer dependent coverage.

Second, it extends eligibility for the Medicaid program to adults who earn less than about $16,000 (or $33,000 for a family of four). In 2012, the Supreme Court made this part of the law optional, giving states the choice to expand the program or not. So far, about half the states—22 states and the District of Columbia, plus six others with customized waiver programs—have done so. Others are still considering the option and may follow suit.

Third, the law establishes insurance exchanges, called marketplaces, where consumers can compare health plans and sign up for coverage. States have the option of running their own marketplaces, or they can default to the federal marketplace, healthcare.gov. Families of four earning less than about $95,400 a year (or individuals earning under $47,000) who buy plans in the marketplaces are eligible for subsidies to help cover the cost of the premiums. For those with incomes under about $30,000 for an individual and $60,000 for a family of four, cost-sharing subsidies reduce the amount people pay in deductibles and copays for doctor visits and other health care services.

All plans purchased in the marketplaces must include, at a minimum, 10 categories of medical services, ranging from doctors office visits and hospital stays to preventive, rehabilitative, and mental health care.

These plans are not subject to annual or lifetime benefit limits, meaning enrollees are protected in case of a catastrophic illness or injury requiring extensive treatment.

The law also requires all citizens and legal residents to purchase health insurance, with an exemption given to people who can't find affordable coverage. In addition, businesses with 100 or more full-time employees this year and 50 or more next year are required to offer affordable coverage, or face penalties if an employee becomes eligible for a subsidized plan through the marketplace.

Less well known are the parts of the ACA that seek to improve the way care is delivered to patients and how providers are paid. Many of these reforms are testing ways of getting patients the right care at the right time, while discouraging hospitals and physicians from providing services that are not only unnecessary and costly, but can do real harm. You can find out much more about these changes, and how providers, payers, and patients are responding to them, here.

What's Working So Far?

Before the Affordable Care Act went into effect, nearly 43 million working-age Americans—more than one-fifth of adults under age 65—were uninsured. According to federal surveys and The Commonwealth Fund's most recent estimates, that number is down to about 30 million, or about 16 percent of the under-age-65 adult population.

Overall, more than 25 million people are estimated to have new or improved insurance through different provisions of the Affordable Care Act: about 11.7 million have selected plans through the insurance marketplaces; another 11.2 million gained coverage because of the expanded Medicaid program; 8 to 12 million purchased insurance directly from an insurer, most of which now comply with the consumer protections in the law; and another 3 million more young adults ages 19 to 25 had coverage under their parents' health plans compared to 2010.

To be sure, not all of the people with new health insurance were previously uninsured; some were simply switching sources of coverage. But according to Commonwealth Fund survey data, more than three of five adults who enrolled in private plans through the marketplaces or signed up for Medicaid had previously lacked any coverage. The uninsured rate for adults ages 19 to 64 fell from 20 percent, just prior to the first open enrollment period in the fall of 2013, to 16 percent by the second half of 2014. Today, the overall uninsured rate is at its lowest level since 2003. That rate is expected to continue to fall as more people continue to enroll in plans sold through the marketplaces and Medicaid in the years to come.

For people who have been without health coverage for a long time—or never had it at all—the initial enrollment process can be a bewildering experience. Graciela Guzman, a "health care navigator" trained to help consumers explore their coverage options in the new marketplaces, said that a lot of the people she talks to in Chicago are a bit wary at first. "Affordability is their primary concern," Guzman explained. "They're very hesitant." However, most are able to find plans that work for them: as many as 90 percent of the people she counsels will receive subsidies. "I have younger guys who are able to walk away with a silver plan and say, ‘Oh, that's the cost of a few pizzas a month. I can handle that,'" Guzman said.

Peter Lee, the executive director of Covered California, the state’s health insurance marketplace, talks about plan choice for individuals and families in his state.

Peter Lee, the executive director of Covered California, the state’s health insurance marketplace, talks about plan choice for individuals and families in his state.In Chicago, Guzman works with a mainly Latino population. "We're trying to change the health status of neighborhoods in urban Chicago that have been without insurance for decades," she said. Their efforts are beginning to help: the uninsured rate among Latinos nationally dropped from 39 percent in 2010 to 34 percent in the second half of 2014.

Subsidies and expanded coverage are having the biggest effects on the people who were previously at the greatest risk of being uninsured: people with low incomes. The uninsured rate for people with low incomes—that is, those earning less than about $48,000 for a family of four—fell from 36 percent in 2010 to 24 percent in 2014.

Having access to coverage is one thing, but being able to pay for it is another. According to survey data, three of five adults with marketplace health plans are finding it somewhat easy or very easy to pay their premiums. People with low and moderate incomes who are eligible for federal subsidies are more likely to find their marketplace plans affordable than are people with higher incomes. Those with higher incomes tend to fare better in employer-based plans, if they are available.

However, even for individuals who are ineligible for premium subsidies, the ability to get coverage through the marketplaces offers a distinct advantage: the freedom to leave a job and strike out on your own, without worrying about health insurance. For Mark Sullivan, the marketplace provided much-needed security when he left his office job to start his own company. The Texas-based technology entrepreneur said that in doing his research, he found "the one cost that was going to go up was health insurance—everything else was going to stay the same or go down."

Sullivan left his job anyway in September 2013, electing expensive COBRA coverage in the months before the marketplace opened, before enrolling in a bronze marketplace plan as soon as he could. The switch saved him more than $200 a month. "It's nice to see a little help for people who are starting businesses," he said. "Anything that increases the mobility of workers and entrepreneurs is something we want in our society. Don't we want people taking calculated risks on new ideas?"

Overall, Americans who have purchased marketplace coverage appear to be satisfied with their new plans. More than two-thirds of adults with marketplace coverage said their health insurance was excellent, very good, or good, according to recent survey data. Sixty percent of adults with new coverage said they had used their new plans to go to a doctor or hospital or to pay for prescription drugs; of those, about the same percentage said they wouldn't have been able to access or afford this care prior to getting their new insurance.

This includes people like Virginia Lindahl of Alexandria, Va. After separating from her partner in 2006, the self-employed clinical psychologist, who suffers from migraines and restless leg syndrome, had few options available to her when she shopped for coverage in the individual market. Eventually Lindahl was able to find a bare-bones plan, one with a $5,000 deductible and an annual limit on coverage. But fearing massive medical bills, she put off getting needed, albeit not urgent, care—a test recommended by her gynecologist, a visit to her allergist, an MRI for her migraines.

When the ACA's first open enrollment period began, she signed up in the marketplace immediately, determined to find coverage that better met her needs. "On that first Monday of January 2014 [after the plan went into effect], I got on the phone with all my doctors and made appointments with all of them," Lindahl said.

In addition to getting more of the care she needs herself, Tanisha Richmond—the self-employed physician who was denied coverage because of her diabetes—is providing it for her patients. Many of her patients who were previously uninsured are now covered under her state's Medicaid expansion. "Now I can give them complete care, compared to the Band-Aid care I had to give," she said. Her business is also doing better. "It increased my cash flow. I had to hire two new employees (medical assistants). It's benefited me, the community, the tax base."

Survey data indicate the ACA is also alleviating personal financial struggles related to medical bills. The number of adults who reported they'd had problems paying their medical bills in the past 12 months or were paying off medical debt, declined from 75 million, or 41 percent, in 2012, to 64 million, or 35 percent, in 2014—the lowest rate in nearly a decade.

Bumps in the Road

Dr. Tanisha Richmond talks about her previously uninsured patients, now covered because of the Affordable Care Act.

Dr. Tanisha Richmond talks about her previously uninsured patients, now covered because of the Affordable Care Act.A lot has gone right with the Affordable Care Act. But no law is perfect—especially one as complex and far-reaching as this one. For starters, most people remember the botched launch of the federal online marketplace. The healthcare.gov website was plagued with problems related to high volume, but there were system and software flaws as well, and many people were unable to sign up. "I woke up at 5 a.m. on October 1st because I was so excited and tried to log on, and you know how that went," said Virginia Lindahl.

It was close to a month before healthcare.gov would be fully operational, but its problems are largely in the past. Similarly, states whose marketplaces functioned poorly in 2014 used the federal website this year to enroll their residents or adopted other states' technology.

Other issues remain, however. The inability of millions of the poorest Americans to purchase affordable coverage is a major one. As we discussed, the Supreme Court made it optional for states to expand Medicaid eligibility, resulting in significant consequences for people in states that have opted out. Millions in those states are now caught in a coverage gap: they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough for subsidies offered in the marketplaces. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that nearly 4 million Americans fall into this gap, most working either full-time or part-time or in a family with a worker. If they remain uninsured, many are likely to defer needed care or, in the case of an accident or emergency, face huge medical bills that put them in debt. In states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility, the rate of uninsured adults with incomes under the poverty level is now 19 percent, compared with 35 percent in states that have not expanded eligibility. Moreover, undocumented immigrants are excluded from the law, meaning they cannot shop for marketplace coverage or qualify for Medicaid. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2020, 30 percent of the remaining uninsured will be unauthorized immigrants.

While the ACA is helping many lower-income people pay for their health care coverage, some people with higher incomes are having more problems affording their premiums and deductibles. That's because, in the marketplaces, subsidies become less generous the higher up the income scale you are. Sixty-five percent of individuals with annual incomes just under $30,000, or $60,000 for a family of four, reported it was very or somewhat easy to afford their premiums. But just over half (54%) with incomes above this level said it was very or somewhat easy to pay.

Again, these higher earners are usually better off with employer-sponsored coverage, when it's available. Nearly 80 percent of higher-income people with health benefits through their job said it was very or somewhat easy to pay their premiums.

What's Next for the ACA?

As the Affordable Care Act passes its fifth birthday, it's clear that the law has met its major goal: increasing the number of Americans with good-quality health care coverage. Some 10 million people have health coverage who didn't have it before. Reaching the millions more who remain uninsured will be a continuing challenge, however, as will ensuring that all those with coverage can afford the out-of-pocket costs that come with getting care.

There are also challenges related to the future of the ACA itself. In June, the Supreme Court is expected to decide the case of King v. Burwell, a challenge to the legality of the subsidies available to people who buy health insurance in the 34 states that chose to have the federal government run their marketplace. The decision has huge implications. Some 11.4 million Americans have selected health plans through the marketplaces, with 8.6 million doing so through a federally run marketplace; of these, more than 7 million receive subsidies. Losing that financial assistance would make insurance unaffordable for many, if not most, of these adults. And if large numbers of relatively healthy people drop their coverage—leaving only the sickest, who can't afford not to be covered—premiums may go up fast, leading still others to cancel their policies.

| * | E. Saltzman and C. Eibner, The Effect of Eliminating the Affordable Care Act's Tax Credits in Federally Facilitated Marketplaces (Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2015). |

| † | B. D. Sommers, S. K. Long, and K. Baicker, "Changes in Mortality After Massachusetts Health Care Reform: A Quasi-experimental Study," Annals of Internal Medicine, May 2014 160(9):585–93. |

Finally, a number of Republicans in Congress continue to promise a repeal of the ACA. While previous attempts haven't gained traction, repeal—or wholesale changes—remains a possibility. A dismantling of the ACA's reforms would mean that millions who have gained coverage and access to affordable health care might once again join the ranks of the uninsured.

Contributors to this report include Sara Collins, Petra Rasmussen, Sophie Beutel, Chris Hollander, Paul Frame, and Joshua Tallman

Designed by Jen Wilson

Developed by Joon Bai