Abstract

- Issue: Rising prices for hospital services paid by private insurance plans have led to interest in government-administered and -regulated pricing systems for commercial payers or regulated rate systems that apply to all payers.

- Goal: To provide background on state-level, government-administered regulated pricing systems, focusing on the characteristics and potential benefits of all-payer hospital global budgets.

- Methods: Review of published literature and analysis of past and existing global budget models.

- Findings and Conclusions: A flexible global budget pays hospitals based on their variable costs for incremental increases or decreases in volumes. This approach may help remove fee-for-service incentives that induce hospitals to provide unnecessary and low-value care, while at the same time giving states a tool to effectively constrain hospital expenditure growth for all payers. Such a payment system is also less complex than systems that set explicit prices or price caps for every service.

Introduction

High hospital prices are responsible for most of the difference between health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries.1 Fueled by increasing levels of hospital consolidation and negotiating leverage, hospital prices paid by commercial health plans in the U.S. have increased rapidly since the early 2000s. In 2018, commercial hospital prices were two-and-a-half times the rates that Medicare pays. There is also strong evidence showing that multiple rounds of hospital consolidation have raised hospital payment levels without improving quality of care or operating efficiency.2

Proposed solutions to the U.S. health care cost problem fall along a continuum from procompetitive initiatives (for example, greater price transparency, tiered- and narrow-provider networks, greater antitrust enforcement) to government regulation of provider prices. While beneficial, strategies to promote competition on their own have not been successful in controlling hospital price and cost growth, because these initiatives do not directly address the market power accumulated by hospitals and other providers.3 Given these circumstances, state and federal policymakers and legislators have voiced renewed interest in the development of government-administered pricing systems.4

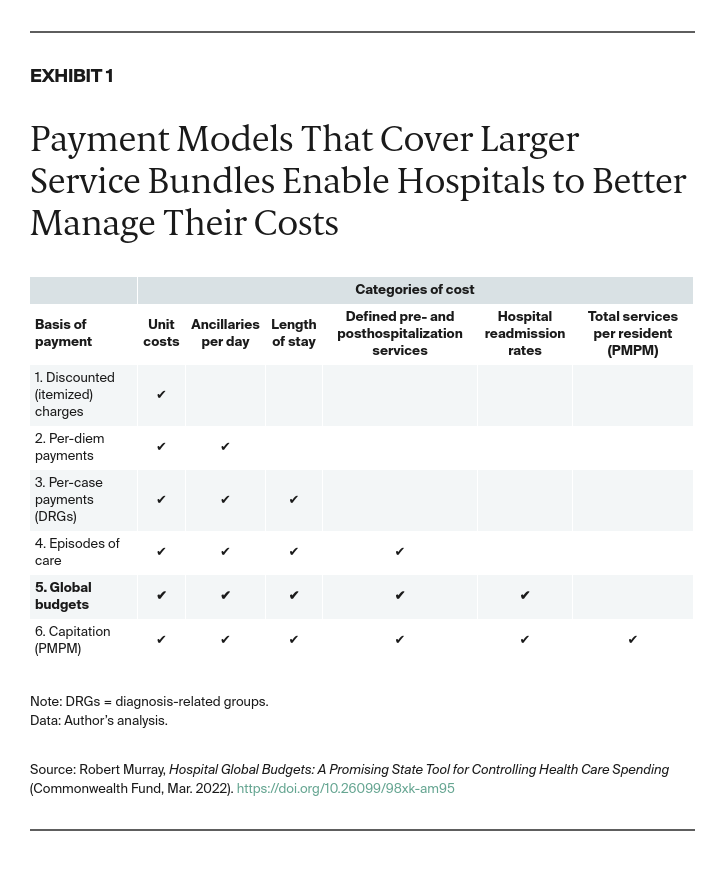

How Global Budgets Expand Opportunities to Manage Costs

Five categories of administered pricing systems applicable to hospital services have been examined in the research literature in recent years:

- Direct itemized pricing: Explicit prices are set for every service or service bundle. Diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments are one example.

- Rate update limits: Restricting the amount by which rates can be increased during negotiations with commercial insurers.

- Price caps for all hospital services: A regulatory agency sets caps on how much hospitals can be paid for specific services; there is usually a rate update limit as well.

- Price caps for out-of-network services only.

- All-payer hospital global budgets: Total revenues are capped for a specified period (typically one year) for all services provided to a patient population.5

While all five of these prospective payment models provide incentives to control costs, the first four pay on a fee-for-service basis (that is, for each test, hospital day, hospital case). This leads to misaligned incentives — providers make more money by providing more services. The more fixed costs a hospital has — for example, building and equipment expenses, administrative overhead, and stand-by staffing costs — the more lucrative it is for the hospital when volumes are increasing. Conversely, hospitals with higher proportions of fixed costs tend to lose money when volumes are contracting (see sidebar) Thus, fee-for-service payment systems tend to induce hospitals to increase the services they provide.6