Abstract

- Issue: Hospitals’ negotiating leverage with commercial insurers and self-funded health plans has led to high and rapidly rising hospital prices. This had led to escalating interest in addressing high prices, including through government intervention in cases where markets have failed.

- Goal: To propose a model of price limits, or caps, on out-of-network hospital services and describe the characteristics, benefits, and limitations of such an approach.

- Method: Review of published literature and analysis of existing models.

- Key Findings: Evidence from the Medicare Advantage program and various state legislative initiatives demonstrate that the use of price caps on out-of-network hospital services indirectly influences in-network negotiated rates. Basing the out-of-network caps on a fixed external benchmark, such as Medicare fee-for-service prices, can help constrain in-network negotiated rates.

- Conclusion: Out-of-network price caps on hospital services may be a straightforward, low-intensity regulatory intervention for reducing in-network prices without direct regulation of in-network rates. As such, it could help improve insurers’ leverage in hospital–insurer price negotiations.

Introduction

Given the extremely high and rapidly rising hospital prices that commercial insurers pay in the United States, prominent health policy experts are now calling for some form of hospital price regulation.1 In particular, a recent proposal to regulate provider prices called for the establishment of price caps (regulated upper dollar limits) on the highest commercial prices along with direct government regulation of provider rate increases.2

Although such a rate regulatory approach has the potential to constrain hospital price growth, a lower-intensity regulatory strategy also can achieve this goal. Capping prices of out-of-network hospital services only, with gradual reductions to those cap levels over time, may also reduce in-network negotiated rates. Hospitals — stand-alone facilities as well as hospitals within health systems — have long exercised their ability to demand large in-network rate increases by threatening to terminate their health plan contracts. Most hospitals use this negotiating strategy to retain their in-network status at high prices. This issue brief discusses a way to reverse the out-of-network negotiating leverage that hospitals currently have.

How Greater Hospital Negotiating Leverage Affects the Market

The U.S. has not had a functionally competitive, efficient private health care market for many decades. Its dysfunction has been greatly exacerbated over the past 20 years by two interrelated factors. The first is the consolidation of hospitals into health systems, likely stimulated by the dominance of managed care in the 1980s and 1990s. Since the early 2000s, this consolidation has allowed hospitals to use their market dominance to extract large rate increases from private payers.

The second factor is the bargaining power of large health systems to set inflated charges for out-of-network care. Many hospitals back up their demands for high in-network rate increases with threats of canceling their existing contracts, which would force the plans to pay high out-of-network charges — often more than 500 percent of Medicare payments.3 This circumstance, which some researchers have referred to as hospitals’ “dynamic negotiating leverage,” is one of most debilitating instances of market failure in U.S. health care.4

When faced with a hospital’s demands for outlandish in-network rate increases, health plans must compare the financial cost of agreeing to the increase versus canceling the hospital contract and paying much higher prices (approximating the hospital’s posted charges) for care to members who use the hospital on an out-of-network basis — principally through the facility’s emergency room. If a substantial proportion of a plan’s members continue to use this hospital, a plan may be reluctant to deny the hospital’s in-network rate demand, because doing so could result in increased total plan costs and a diminished network.5 An example of the negotiating dilemma that plans face in their negotiations over in-network rates is shown in Exhibit 1.

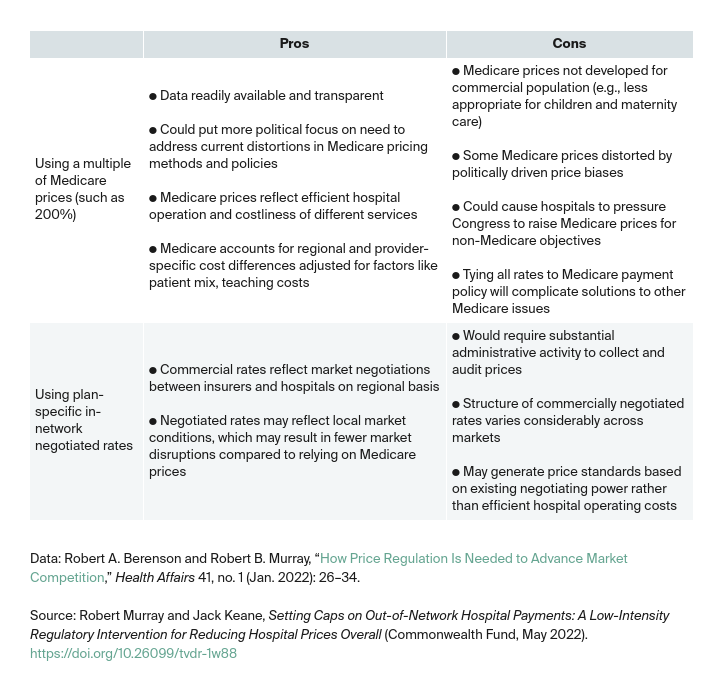

Exhibit 1. Dilemma Facing Health Plan Confronted with Hospital’s Demand for In-Network Rate Increase

A hypothetical health plan currently pays its contracted hospitals 250 percent of Medicare rates. Hospital A suddenly demands an immediate 10 percent increase to its in-network rates with no demonstrated need or justification. The hospital’s posted charges (and the amounts it requires out-of-network insurers to pay for care to the insurer’s members) equals 450 percent of Medicare.

If the hospital goes without a contract, 30 percent of plan members will continue to use this facility, primarily on an emergency basis. The plan can divert the remaining 70 percent of members, previously using the hospital, to other in-network hospitals at the original contracted rate of 250 percent of Medicare.

Scenario 1: Grant the hospital its 10 percent demanded rate increase to its in-network contracted rates.

Scenario 2: Hospital cancels its contract with the health plan, and the plan pays the hospital billed charges for members continuing to use the hospital.

Given these circumstances, the health plan concludes it would be more cost-effective to grant Hospital A its demanded 10 percent in-network rate increase (Scenario 1). That is because the alternative scenario, letting the hospital go out-of-network, would result in the plan paying 310 percent of Medicare for patients who previously used this hospital.

Based on the assumptions used in this example, Hospital A could theoretically demand an in-network negotiated rate increase as high as 24 percent — from 250 percent to 310 percent of Medicare — before it would make economic sense for the plan to refuse the hospital’s rate request and terminate the contract. This potential in-network negotiated rate increase is a marker of Hospital A’s dynamic negotiating leverage over the plan.

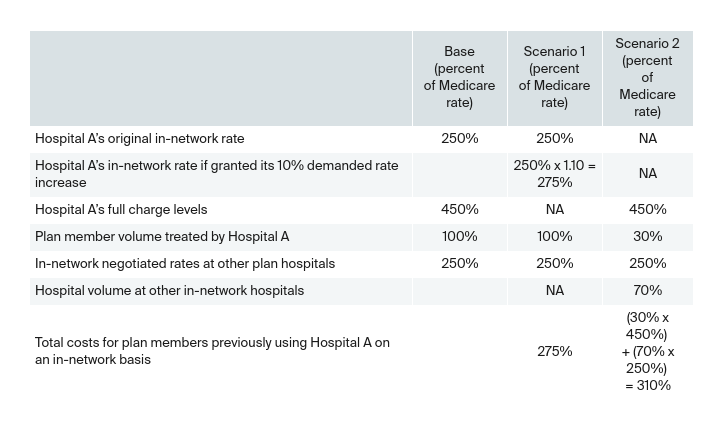

Out-of-Network Price Caps Can Help Insurers Negotiate Lower In-Network Rates

The imposition of out-of-network price caps can counteract the dynamic illustrated in Exhibit 1 and increase health plans’ leverage in two ways. First, with prices regulated, hospitals are less motivated to remain out of network, giving insurers additional negotiating leverage that could result in lower in-network rates.

Second, once an out-of-network price cap has been established, an insurer has the ability to break off negotiations with a hospital and pay only the capped price for services rendered on an out-of-network basis. Having this leverage, the insurer can now insist on in-network price levels that are at or near the level of the out-of-network price cap.6

These indirect impacts of out-of-network caps on in-network negotiated rates seem to occur in the private Medicare Advantage market. Thanks to a federal prohibition on the balance-billing of patients and a statutory requirement that out-of-network providers be paid at traditional Medicare (fee-for-service) price levels, Advantage plans have been able to negotiate in-network rates at or very close to traditional Medicare rates.7 Other studies indicate that states with caps on out-of-network billing, established through comprehensive legislation to combat surprise billing, have experienced drops in in-network negotiated prices.8

While the No Surprises Act should help reduce in-network negotiated rates by placing limits on out-of-network prices (see box), more action is needed to counter hospitals’ negotiating leverage.9 Introducing state-legislated price caps for out-of-network services, at or slightly below current in-network negotiated price median levels, could restore negotiating balance to the commercial market. Moreover, a system of gradually reduced out-of-network price caps, from the initial levels recommended above, could further enhance plan negotiating leverage and result in reductions in in-network negotiated rates over time.

A system of gradually reduced out-of-network price caps also would allow a state to monitor any associated impacts on patient access, quality of care, and provider financial condition. States may also be attracted to this approach because, from a regulatory standpoint, it is the least intrusive with regard to negotiations between providers and insurers (regulated price caps would apply to out-of-network care only, a small segment of the market).