Summary: After receiving failing grades on composite measures of birth outcomes released by organizations such as the March of Dimes for years, Louisiana funded a comprehensive program to improve the health of women of child-bearing age. This initiative has fostered collaboration among state agencies, provider associations, and community groups, creating the momentum needed to solve what has historically been an intractable health care quality problem.

By Vida Foubister

Issue: Louisiana performs worse than nearly every other state in the nation on measures of infant mortality, preterm birth, low birth weight, and caesarian sections. These poor maternal outcomes take a tremendous social and financial toll on the state and its residents. Many premature infants born to Louisiana mothers die shortly after birth, and those that survive often suffer from physical, neurological, or educational disabilities. The average cost of caring for these premature infants ($33,000) is more than eight times the average for term infants nationally.1 As Louisiana's Medicaid program covers nearly 70 percent of all births—the country’s second-highest Medicaid birth rate—the state spends more than $200 million annually on these additional medical services.2

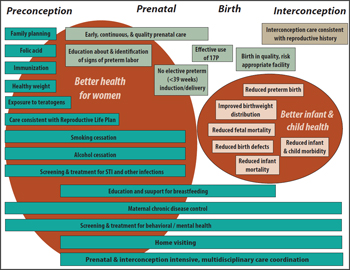

To address these challenges, the state launched a multifaceted effort to improve the health of mothers and their children in November 2010. The Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative has worked to create baseline measures of maternal and child health and to identify and implement evidence-based interventions. These include changes in data measurement, hospital standards and medical practices, as well as assessments of mothers' and families' needs to enable health care providers and others to address the social, behavioral, biological, and genetic factors associated with poor birth outcomes (see figure).

Figure: Range of Interventions to Improve Women's Health

Source: Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative

Population Served: The Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative (BOI) aims to improve care—and expand its availability—to women of child-bearing age before, during, immediately after, and between pregnancies. The women the program serves are predominately African American and poor (Louisiana has the nation's second-highest poverty rate). They not only suffer from tremendous social challenges including violence, racism, crime, and poor education but also have high rates of drug and alcohol addiction, behavioral health problems, obesity, HIV, and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Program and Leadership: Governor Bobby Jindal initiated the state’s focus on birth outcomes by establishing a 16-member Commission on Perinatal Care and Prevention of Infant Mortality to identify key performance indicators and aggressive public health strategies to address them. This led Bruce D. Greenstein, secretary of the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals (DHH), to champion the issue and designate poor birth outcomes as his top priority for improvement. The Birth Outcomes Initiative that resulted from these efforts has three staff members: Rebekah E. Gee, M.D., M.P.H., its director, is the state’s medical director of Medicaid and an assistant professor of public health and obstetrics and gynecology at Louisiana State University; Michelle M. Alletto, M.P.A., is the program’s deputy director and clinical services manager of the state’s Bureau of Family Health within the Office of Public Health; and Caroline Brazeel is the program coordinator. The BOI is housed within the DHH Office of the Secretary, enabling the team to work across agencies to assess what each is doing to improve birth outcomes and to find ways they can work together to reduce duplication and have greater effects on care.

Process: Relying on input from a panel of national leaders in maternal and child health and Childbirth Connection’s Blueprint for Action, which identifies 11 strategies for achieving a high-quality, high-value maternity care system, the BOI decided to focus on:

- data and measurement;

- patient safety and health care quality;

- care coordination;

- health disparities; and

- behavioral health.

The BOI then engaged five statewide "action teams"—together composed of more than 80 representatives from medical professional organizations, hospitals, health plans, providers, consumers, and community partners—to make recommendations on how best to achieve change in each of these focus areas. Based on the action teams' recommendations, multiple projects were initiated.

Prevent Elective Deliveries Prior to 39 Weeks

Elective, preterm deliveries in Louisiana and elsewhere are a leading cause of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions. A key focus of the BOI has been to prevent mothers and physicians from scheduling deliveries—without medical indications—prior to 39 weeks gestation. The BOI chose a collaborative approach to address this issue, one that focuses on a voluntary commitment from hospitals, giving them time to review their policies and reach consensus on documenting medical necessity for inductions and cesarean deliveries, and education and coaching of providers and patients, helping them to understand the negative health implications of preterm deliveries. By January 2012, all of the state's 58 birthing hospitals had pledged to work toward the BOI’s goal.

Learning Collaborative Engagement

Through a partnership between the BOI and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), 28 of Louisiana’s 58 birthing hospitals have participated in the IHI’s Perinatal Improvement Community. (The financial costs to hospitals were minimal, as the BOI negotiated a reduced rate for the group and the state and other organizations paid for some or all of the hospitals costs). Collaborative leaders first helped participating hospitals identify opportunities for improvement and then coached them, both directly and through peer-learning opportunities, on implementing proven improvement tools and practices.

The IHI’s Perinatal Improvement Community is focused on four key areas to eliminate harm to mothers and their children: leadership support, reliable design, effective teamwork, and engaging with patients and families. The initial aim defined by the Louisiana hospitals was to decrease—to zero—the rate of early elective deliveries, using the IHI’s elective induction bundle of evidence-based interventions. Many hospitals that are participating in the collaborative for the second year have begun working to reduce the cesarean section rate among mothers delivering their first child at term, a rate that varies widely and carries significant costs, says Sue Gullo, R.N., M.S., a director at IHI.

Hospitals participating in the IHI collaborative report their outcomes monthly, providing an early indication of the initiative’s effectiveness. Among 14 hospitals participating for the second year in the collaborative, the rate of elective deliveries prior to 39 weeks have decreased from a weighted average of 15 percent to a current weighted average of less than 2 percent.3 There has also been a reduction in NICU admissions at many of these hospitals. Woman’s Hospital in Baton Rouge, for example, saw a 23 percent decrease in NICU admissions and North Oaks Medical Center in Hammond a 25 percent decrease. Lafayette General Medical Center's elective-delivery rate prior to 39 weeks dropped from nearly 30 percent in November 2011 to 4 percent by June 2012.

Improved Data Collection on Medical Indications for Early Elective Deliveries

The state has been working to establish baseline maternity quality metrics, without which it will be unable to validate improvements. One of these efforts focused on modifying the Louisiana Electronic Event Registration System (LEERS), a Web-based vital records system that records data on births, deaths, fetal deaths, marriage, and divorce, to enable the state to document the reason deliveries are done prior to 39 weeks. The LEERS Birth Module now includes a number of medical indications, developed with input from national clinical and quality experts, the state registrar, the state Maternal and Child Health epidemiologist, and Louisiana hospitals and providers, to specify why a preterm birth was appropriate. The state began collecting data on these early deliveries in March 2012 and plans to release its findings once the data have been validated.

Institute Statewide, Comprehensive Behavioral Health Screening

To address Louisiana’s high rates of behavioral illness—which exceed national averages—and mitigate their contribution to the state’s poor birth outcomes, the BOI developed an online tool to streamline the screening and referral process for alcohol, tobacco, and substance abuse and domestic violence. Called LaHART for Louisiana Health Assessment, Referral and Treatment, it was modeled on a World Health Organization tool and is being launched in stages, starting with a pilot site last June. The goal is for providers to use the screening tool during the first prenatal visit “to identify any problems as early as possible,” Brazeel says. Providers are reimbursed $14.49 for using the screen, and $33.81 for a brief intervention. LaHART facilitates easier referrals for several cases: for women who want to quit smoking, providers can click a button to initiate contact with the Louisiana Tobacco Quit Line, which provides 10 calls with a quit coach throughout a woman’s pregnancy; for alcohol and drug abuse, women are connected to a recovery care manager at Magellan, the state’s managed behavioral health plan, which connects them with expanded case management and provider network options; and women suffering from domestic violence are referred to the state’s Domestic Violence Hotline to develop a safety plan if they are not ready to leave their abuser.

As more hospitals and clinics implement LaHART, the BOI plans to begin collecting data on the number of women screening positive in each category and, of those identified, the number who are referred for treatment.

Improve the Continuum of Care

Recognizing that woman of child-bearing age need to be healthy not only during their pregnancy but also before, immediately after, and between pregnancies to ensure good birth outcomes, the BOI initiated several programs to address women’s overall health needs. Some of these programs focus on identifying women with prior poor birth outcomes and ensuring they have access to the health and social services necessary to prevent such outcomes from occurring again.

Better Perinatal Care

In partnership with the Louisiana Hospital Association, the BOI established a Web site to make it easier for providers to order and be reimbursed for administering 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate, also called 17P or Makena. Mothers who have prior preterm births are 2.5 times as likely to have another; treatment with this hormone has been shown to reduce the rate of repeat preterm birth by about 33 percent in appropriate candidates. Preliminary state estimates suggest that about 6,000 Louisiana women are eligible for the injectable drug, but billing data show that less than 1 percent of them are being prescribed it. To encourage the drug’s use, the Web site provides information to providers in a centralized place on ordering 17P and receiving reimbursement from various health plans.

Expand Access to Interconception Care

Nearly three-quarters of the women receiving health care through Medicaid lose their eligibility for the program 60 days after their babies are born, which makes it difficult for them to receive care for any chronic or acute diseases until their next pregnancy, putting their future infants at risk.

A federal demonstration waiver approved in September 2010 following Hurricane Katrina enables uninsured New Orleans residents ages 19 to 64 who fall under the 200 percent federal poverty level to receive care through Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection clinics, which operate as primary care medical homes. Beginning in July 2012, these services were expanded through a state pilot program to include comprehensive interconception care for Medicaid-eligible women in New Orleans who have recently given birth to a preterm or low birth weight baby or who experienced a fetal or infant death. “To have a healthy pregnancy, you need to be healthy before pregnancy,” Gee says. “There’s only so much that can be done when you’re already pregnant.”

Through door-to-door outreach to 439 households, Healthy Start New Orleans has enrolled 56 women in intensive, inter-pregnancy care case management. Healthy Start case managers connect them to primary care services at the Greater New Orleans Community Health Connection clinics, with the goal of improving their management of any chronic conditions as well as their overall health. They also educate these women about family planning and help them to receive additional services such as nutrition and weight counseling, immunizations, STD screening and treatment, and substance abuse and mental health referrals and treatment.

Improve Postpartum Care

CMS recently awarded the Louisiana BOI a two-year, $2-million Adult Quality Measures Grant to ensure postpartum visits occur, to improve the quality of those visits, and to measure postpartum health. Gee is currently working to execute the grant, which will use 39-week birth data to support quality improvement initiatives involving the five health plans that make up Bayou Health, the state’s new Medicaid managed care plan.

Participate in National, State, and Local Collaborations

Based on its belief that the public sector’s effectiveness can be enhanced through partnerships, the BOI has made participation in multiple initiatives and collaborations a priority. This includes partnerships that focus on racial, economic and social determinants of disease, which are believed to significant contributors to disparities and infant mortality.

Best Babies Zone

New Orleans was one of four cities to receive a $400,000 grant from the W. K. Kellogg Foundation to improve birth outcomes. Using that funding, New Orleans has embarked on a community-based initiative to reduce infant mortality, household poverty, high school dropout rates, father absence, and racial-ethnic and socioeconomic disparities. “The Best Babies Zone approach is unique in that it seeks to address the social determinants of health by building partnerships across multiple sectors to address a health issue,” says Kim Williams, M.P.P., program director at Healthy Start New Orleans. It is modeled on the Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership in Harlem, a 10-year initiative that reduced African American infant mortality by 50 percent. (Central Harlem’s infant mortality rate decreased from 27.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 6.1 deaths in 2008.)

In New Orleans, Best Babies Zone grantees are working in the Hollygrove-Dixon neighborhood, an area with above-average rates of low birth weight babies and community leaders interested in engaging in the project. From 2006 to 2010, 18.4 percent of all births to women in Hollywood-Dixon were low birth weight, or less than 5.5 pounds, compared with 12.5 percent in Orleans Parish. Since July 2012, Best Babies Zone has initiated door-to-door outreach—engaging 18 women through an initial needs assessment. These women have agreed to receive monthly home visits and work with a case manager to access primary care and family planning services. The Best Babies Zone initiative is also conducting an environmental assessment of the neighborhood and strengthening partnerships with local providers and organizations. This includes working with the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority to reduce blight and increase affordable housing and with Job One to increase access to job readiness and placement. “In New Orleans, where violence is prevalent, many of the neighborhoods with high rates of low birth weight also experience high crime,” says Williams. “I believe the two are inextricably linked. When babies are born too small, or too soon, they face developmental challenges, particularly brain development that can lead to behavior problems and later violence.”

Other Collaboratives

- Louisiana was the second state to join the March of Dimes/Association of State and Territorial Health Officials partnership to reduce preterm births to 8 percent or less by 2014, as measured against 2009 data. (According to the March of Dimes, which bases these rates on National Center for Health Statistics data and defines preterm birth as less than 37 completed weeks of gestation, Louisiana’s preterm birth rate was 14.7 percent in 2009 and, most recently, 15.6 percent in 2012).

- In December 2012, Louisiana was one of four states selected to participate in the National Governors Association Learning Network on Improving Birth Outcomes, which aims to help states develop, implement, and align policies to improve birth outcomes, both through in-state and networking conferences.

- Louisiana is one of 13 states (from Public Health Regions IV and VI) participating in the Health Resources and Services Administration Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (COIN) to Reduce Infant Mortality, which grew out of an Infant Mortality Summit held in New Orleans last year.

Initiative Financing: DHH Secretary Greenstein funded the BOI as $1 million standing budget item, beginning with fiscal year 2011; funding has been maintained at this level for three years. Recognizing the financial challenges facing state governments, and with additional funding coming from federal and foundation sources, the BOI has requested about half this amount for 2014. “We want to be as fiscally tight as possible,” says Alletto.

Lessons Learned: Louisiana chose a voluntary approach to build trust with state providers. “If we had started with a stick, the project would have failed,” says Gee. (Medicaid agencies in other states have taken a more punitive approach. South Carolina and Texas, for example, chose to deny reimbursement for non–medically indicated deliveries prior to 39 weeks, something that might have the unintended effect of discouraging medically appropriate preterm deliveries.)

The BOI is also taking a collaborative approach in its development of a hospital-based report card for maternity and NICU care. Four quality measures—rates of very low birth weight babies, preterm births, c-sections, and low-risk c-sections—have been developed and are being piloted in a limited number of hospitals. They are also working with a DHH analytics team to develop appropriate risk adjustments for providers who, by nature of their location or specialty, handle higher-risk deliveries. Once they have enough confidence in their data collection methods and metrics, the BOI plans to release the data publicly. However, as the local provider culture is resistant to public reporting, it remains unclear what this public-facing report will look like and when it will be released. “The end goal is to make providers and hospitals improve their quality and be held responsible for good outcomes for moms and babies,” says Alletto.

Another area the BOI has focused on is collaborating with other state agencies and organizations to share best practices. Initially, this required Gee to call others working on improving birth outcomes. However, since the initiative was launched, several formal networks have been established.

Partnerships with community organizations including the Best Babies Zone initiative, which focuses on social determinants of birth outcomes, have been a critical component of the state’s efforts to address issues that fall outside of health care. “Stress such as that experienced due to racism, community violence, lack of access to resources, poor housing, etc. can impact women’s health and subsequently their pregnancies and newborn children,” says Williams.

Gee admits that the BOI approach was perhaps too far-reaching, as it failed to develop approaches to address health disparities—one of its five priority areas and a problem that is systemic to the state. “I don’t think you can talk about health outcomes in the South without talking about disparities,” says Gee. Still, this breadth enabled team members to focus on projects that were moving forward fast and put off those that met roadblocks. “You’ve got to attack multiple targets to effect change because there’s more than one thing that goes into a poor birth outcome, but you can’t win on all fronts,” she says.

For further information, contact Rebekah E. Gee, M.D., M.P.H., Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative director, at [email protected].

1 R. E. Gee, M. M. Alletto, and A. E. Keck, "A Window of Opportunity: The Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative," Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, June 2012 37(3):551–57.

2 Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative, Case Study, October 2012. (Washington, D.C., National Governors Association; 2012). Available at: http://statepolicyoptions.nga.org/sites/default/files/casestudy/pdf/Louisiana%20-%20Birth%20Outcomes%20Initiative.pdf. R. E. Gee, M. M. Alletto, and A. E. Keck, "A Window of Opportunity: The Louisiana Birth Outcomes Initiative," Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, June 2012 37(3):551–57.

3 This is measured in accordance with the Joint Commission National Quality Measures manual. Perinatal core measure 1 (PC-01) is a process measure for elective deliveries that is determined by dividing the number of patients with elective deliveries by the number of patients delivering newborns between 37 weeks and 38 weeks and 6 days gestation. Please see the manual for further details.