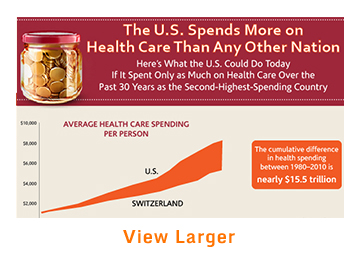

Even if you’re not an expert on health care or the Affordable Care Act, you’ve probably heard that the costs of care in the United States are high—really high. Maybe you’ve even heard that the U.S. spends more on health care than any other country. But what does it mean? Why does it happen? And can we do anything about it?

For starters, the $2.9 trillion we spend annually on health care—a whopping $9,200 per person—isn’t necessarily buying us the best care or ensuring good health. In fact, not only does the U.S. fare worse in terms of infant mortality and life expectancy than other developed nations, it also tops the list for deaths that are considered preventable with timely and appropriate treatment. What’s more, a hospital stay or common diagnostic tests, like MRIs, cost many times more in the U.S. than in countries like Germany or Japan.

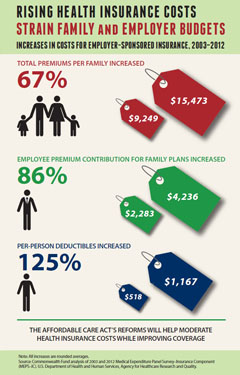

These high costs place a heavy burden on government, which funds Medicare, Medicaid, and other public insurance programs; on employers, who help pay for the health coverage of workers and their families; and on American households, who feel the pain in their pocketbooks, through higher taxes and reduced wages.

Getting at the Root of the Problem

Before we learn about these new approaches to paying for health care, let’s take a closer look at where costs really pile up.

Paying for More Doesn't Always Get You More

Many experts point to the way health care providers in the U.S. are typically paid for the services they deliver as a major culprit in driving our out-of-control costs. Under our fee-for-service system, most physicians, hospitals, and other providers receive a payment for each service, be it an office visit, lab test, or medical procedure—regardless of whether or not they help (or harm) the patient. In other words, provider payment is based on the quantity of care provided, rather than the care actually needed by the patient, or the effectiveness of the treatment.

Providers usually don’t feel pressure to limit themselves from prescribing services that may not be necessary. And physicians’ fear of malpractice lawsuits may actually contribute to the problem by encouraging the practice of “defensive medicine.” Likewise, since most patients are shielded from the bulk of costs by their health insurance coverage, they may be inclined to welcome any medical service that has even the slightest chance of doing some good.

Poorly Coordinated Care

It surprises many people to discover that a very small portion of the U.S. population—just 5 percent—accounts for nearly half of total spending on health care, while 20 percent accounts for four-fifths of total spending. This relatively small slice of the population incurs such high costs because most of these individuals have complex medical problems. The problems include common but difficult-to-manage chronic diseases like diabetes and heart failure, as well as mental and behavioral health issues. Chronically ill people take more prescription drugs, undergo more tests and procedures, and are hospitalized more often than people in good health.

But the costs for these patients really skyrocket when the care they receive is poorly coordinated: when patients are referred by their primary care provider to a specialist, move in and out of the hospital, and transition from the hospital to home care or a long-term care facility, all with little oversight or communication between providers. In this environment, patients may undergo the same lab tests multiple times, they may get the wrong combination of medications, and serious conditions may get misdiagnosed. This not only leads to unnecessarily high costs, it also means poor care for the patients who most need help.

Avoidable Hospital Readmissions

One of five elderly patients discharged from hospitals in the United States ends up being readmitted within 30 days, costing Medicare alone upwards of $17 billion each year. Many of these readmissions could be prevented, and billions saved, if hospitals, doctors, and community health programs worked together to assist patients who are returning home or moving on to a nursing home or rehab facility. Discharged patients need clear instructions on how to care for themselves at home, as well as help in scheduling and keeping follow-up appointments, sticking to a prescribed medication plan, and making necessary lifestyle changes.

High Prices

In the U.S., costs for office visits, lab tests, medical procedures, hospital stays, and prescription drugs are often much higher than in other countries. For example, the average cost for a day in a U.S. hospital is $4,287; in France, it’s $853. The total price for a normal birth is nearly $10,000 in the U.S.; in the United Kingdom, it’s $2,641. A knee replacement? Over $25,000 here—more than twice the cost in Switzerland.

The price discrepancy extends to doctors' bills, too. U.S. physicians receive substantially more for office visits—for example, by Medicare and Medicaid—than their counterparts in other high-income countries. To make matters worse, prices for the same services, such as lab tests or mammograms, vary significantly between providers, even in the same city or county.

It is estimated that the U.S. spends up to one-third of its health care dollars on medical services that do nothing to improve our health—and which may even be harmful. This “excess care” can be a byproduct of poor care coordination, such as when a patient has an MRI in his doctor’s office and then another one two weeks later in the hospital.

Excess care also stems from quality and safety problems. Each year, thousands of patients are treated for problems that shouldn’t have occurred in the first place, such as a serious infection picked up in the hospital. Overtreatment is also a big problem: opting for surgery, when medication or a less-invasive procedure would be equally effective (and less risky), is just one example.

Together, the combination of overuse and misuse of medical services, along with elevated prices, helps explain why quality of health care in the U.S. doesn’t match our nation’s high level of spending.

A Solution: Bringing Accountability to Health Care

To get to a health care system that’s affordable yet provides high quality, we need to tackle the issues that have made things so expensive in the first place. Wholesale cuts to Medicare and Medicaid might reduce spending in the short term, but they would also mean slashing benefits and reducing access to care.

A better solution might be found in the dozens of innovative and promising experiments already under way in both the public and private sectors to transform how patient care is delivered and how we pay for it. Here are some of the more promising ideas, along with real-world examples of how they work.

Bundled payments. By paying health care providers one lump sum for all the services needed to treat a patient with a particular condition or illness, the incentive to do more simply to earn more disappears. Instead, the emphasis shifts to providing care that helps the patient get well quickly—and stay well. For a patient requiring cardiac bypass surgery, rather than making one payment to the hospital, a second payment to the surgeon, and a third to the anesthesiologist, the insurer combines these payments into a single, bundled payment to be divided among all the clinicians. In a similar fashion, a bundled payment for treating a diabetes patient might represent a year’s worth of primary care visits, blood glucose monitoring tests, preventive services, and hospitalization.

Bundled or “episode-based” payments are most often used for common, high-cost procedures, including bypass surgery, joint replacement, or maternity care and delivery. Functioning as a team, providers coordinate patients’ care, rely only on cost-effective treatments, and keep tabs on patients once they leave the hospital to monitor for complications. If the cost of effective treatment is less than the bundled payment, the provider team can share the savings.

Recently, Medicare announced that more than 500 hospitals and related health care organizations agreed to bundled payments for all the care associated with four dozen conditions and procedures, including stroke and joint replacement.

Global payments. While bundled payments cover all health services used to treat a particular illness, condition, or injury, global payments are paid to a single health care organization for providing all needed care for a specific population—the employees of a large company, say, or people living in a certain geographic area.

Global payments—sometimes called capitated payments—have been used in health maintenance organizations, or HMOs, for years. In the 1990s, consumers chafed against HMOs’ limited choices of providers and denials of care that seemed to be based solely on cost. Although costs did go down, to many people quality of care suffered.

The new global payment model is fundamentally different, because we have tools to make sure that the focus isn’t just on saving money. Health care providers must also meet certain quality criteria, like offering timely preventive screenings and promptly following up on test results with patients. They also receive bonuses if their patients stay healthy and avoid costly hospitalizations—an incentive that benefits everybody.

Accountable care organizations. A new way of delivering and paying for patient care that is starting to take hold is the accountable care organization, or ACO. Typically, an ACO is a partnership between a payer, like a health insurance plan, and a group of providers—primary care physicians, hospitals, specialists, rehabilitation centers, and long-term care facilities—that agree to share responsibility, and sometimes the financial risk, for delivering quality health care to a population of patients.

The ACO receives a payment from the insurer, whether Medicare or a private plan, to cover the cost of providing all the care needed by these patients. In addition, the ACO providers get to share in the savings if they meet cost and quality targets for their patients. On the flip side, providers that participate in some ACOs also agree to accept penalties if they go over budget. Unlike HMO enrollees, ACO patients have the choice of seeing doctors outside the organization.

Although the accountable care concept is still evolving, already one of every 10 Americans gets their care from one of more than 400 ACOs nationwide. ACOs strive to deliver care that is most appropriate for the patient rather than providing as many services as possible. The goal is to reward providers for keeping patients healthy—and out of the hospital.

What's in it for Me?

Private insurers—as well as the government, through the Medicare program—are starting to see some results. If progress continues, people enrolled in ACOs and other programs will receive better overall care and be in better health.

For employers, a healthier workforce means cost savings. Under the health reform law, all businesses with more than 50 full-time employees will have to provide coverage to their workers or face fines. But if insurance plans that adopt the new payment models can reduce costs and keep enrollees in better health, employers could see higher productivity and lower premiums for themselves and their employees.

Final Thoughts

In the battle to control health care spending, the stakes are high. The more the government devotes to health costs, the less it has available for investing in jobs, education, and other pressing societal needs. Businesses—large and small alike—are hamstrung, too. With health insurance premiums running so high, many small employers simply cannot afford to offer health coverage and raise wages for their workers. And large firms in many industries must contend with crippling obligations to thousands of retirees with health benefits.

We know for certain that more spending does not translate into better care or a better-functioning health care system. Although there have been some recent signs of a leveling off in spending, that doesn’t mean the problem has been fixed. Not even close.

The good news is that a lot of activity is already taking place in the private and public sectors to obtain greater value for our health care dollars. These include not only the accountable care systems you’ve read about here, but also new incentives that encourage providers and patients to make the best health care choices, efforts to expand access to medical homes and primary care, and initiatives to promote greater use of information technologies to focus health care resources where they’re needed most.

The good news is that a lot of activity is already taking place in the private and public sectors to obtain greater value for our health care dollars. These include not only the accountable care systems you’ve read about here, but also new incentives that encourage providers and patients to make the best health care choices, efforts to expand access to medical homes and primary care, and initiatives to promote greater use of information technologies to focus health care resources where they’re needed most.

It will be an uphill battle, but it’s within our grasp if we all play our part.