Twelve years ago, I traveled around the country meeting individuals and families who were scraping by without health insurance. Last year, I returned to the communities I visited to hear how the people I had met earlier were faring in the era of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The five people featured in these video essays—Taneila, Cindy, Laura, Joyce, and Marcellus—live in small and midsized towns in south-central Illinois. These five—like all 31 of the formerly uninsured Illinois residents who I interviewed in 2003—were insured in 2015.

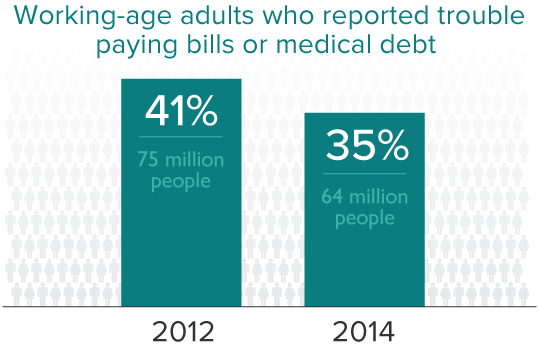

In 2003, all five seemed stuck in spirals of deteriorating health, low-wage employment, and medical debt, with no obvious way forward. Taneila was a young part-time college student with diabetes who was supporting herself with a part-time job. Cindy, fully immersed in caring for her special-needs baby, had left the workforce. Laura was working in the hotel industry. Joyce was working on and off as a nursing home aide and her husband, Marcellus, was working full time in a warehouse. All had applied for Medicaid but did not qualify under pre-expansion rules that limited coverage to low-income parents and severely disabled adults.

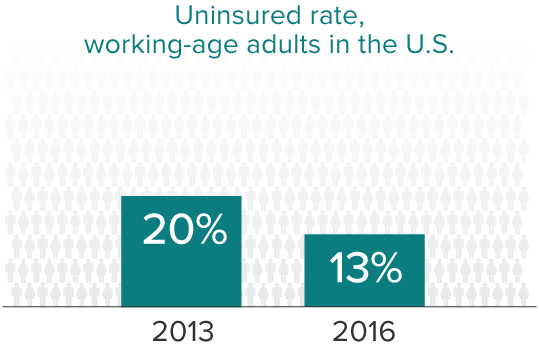

The Affordable Care Act has opened several paths forward. Many people can purchase reasonably affordable insurance through insurance marketplaces that lay out the costs of health plans and provide subsidies for low- and moderate-income consumers. Although the Supreme Court decision made Medicaid expansion a choice for states, low-income residents of states like Illinois that have expanded coverage—such as Laura and Joyce—have Medicaid as an affordable option as the law intended. Unfortunately, many of the people I caught up with in Texas, Mississippi, and Idaho—states that have so far declined the Medicaid expansion—are still uninsured.

In addition, thanks to the ACA, young adults can stay on their parents’ coverage until age 26 and employers of 50 or more full-time employees are now required to cover their workers. Today, Taneila works for an employer with health insurance benefits. While Cindy continues to cycle on and off coverage with her seasonal job, Marcellus is now insured through both Medicare and Medicaid. Yet all live with the repercussions of having been uninsured for long periods. I encourage you to hear their stories.

Taneila

A Young Adult's Limited Access to Coverage Before the ACA

Taneila grew up with reliable health insurance. As the daughter of a member of the military, she never thought about being unable to go to the doctor. She had easy access to high-quality care, which is why when she was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at age 16 she assumed that she would always be able to keep her health under control.

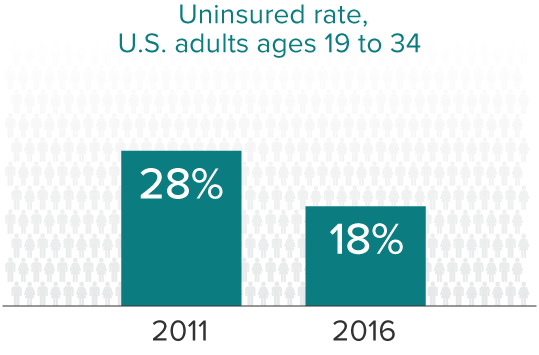

What she did not realize at the time was that she would soon lose her coverage. Prior to the ACA, many young adults were not able to stay on their parents’ insurance beyond age 18. In fact, allowing all young adults to remain on their parents’ insurance up to age 26 has been one of the biggest successes of the ACA. In just the first three years after the law went into effect, nearly 8 million additional young adults enrolled in a parents’ health plan.

Taneila had looked forward to going to college in the university town of Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, where she’d grown up. But her college life was dominated by her lack of insurance and declining health. Working part time at Walgreens while attending school full time, she often did not have the $100 to pay for her monthly insulin. Even more important, Taneila says, she didn’t learn how to manage her diabetes. “I wasn’t well informed,” she says.