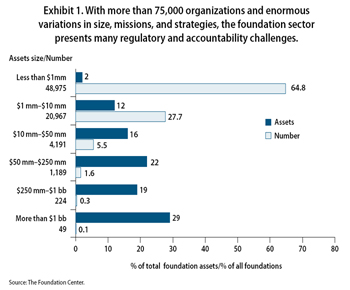

Today there are more than 75,000 private foundations in the United States, with total assets of around $565 billion.1 The size distribution of these organizations is highly skewed: 273 large foundations with endowments of $250 million or more account for 48 percent of the sector’s total resources (Exhibit 1). On the other end of the distribution, some 49,000 very small foundations with assets under $1 million hold about 2 percent of the sector’s wealth, and another group of 21,000 with assets between $1 million and $10 million hold 12 percent. This diversity of size is more than matched by diversity of missions, operating models, goals, and strategies—making the objective of ensuring the accountability and performance of these important institutions a formidable one.

Today there are more than 75,000 private foundations in the United States, with total assets of around $565 billion.1 The size distribution of these organizations is highly skewed: 273 large foundations with endowments of $250 million or more account for 48 percent of the sector’s total resources (Exhibit 1). On the other end of the distribution, some 49,000 very small foundations with assets under $1 million hold about 2 percent of the sector’s wealth, and another group of 21,000 with assets between $1 million and $10 million hold 12 percent. This diversity of size is more than matched by diversity of missions, operating models, goals, and strategies—making the objective of ensuring the accountability and performance of these important institutions a formidable one.

Private foundations exist under the watchful eye of the United States Congress, which has delegated their oversight to the Internal Revenue Service. In each state, offices of the state attorneys general also bear regulatory responsibility, but because of the limited resources typically available for this purpose, the IRS is by default the only real regulator of foundations—except in instances where an attorney general has been alerted to the possibility of significant misbehavior by a foundation.

To obtain the information needed to exercise its regulatory responsibilities, the IRS relies principally on an annual filing by private foundations—the Form 990-PF tax return. While it also conducts periodic audits of individual foundations, the sheer number of organizations, together with the IRS’s record of reaping minimal revenue from costly audits, makes the 990-PF filing the overwhelming choice of regulatory tool. The 990-PF also provides foundations with an important tool for self-regulation, helps journalists serve as accountability watchdogs, and generates data used by the Foundation Center to maintain its databases and research reports on the foundation sector.2

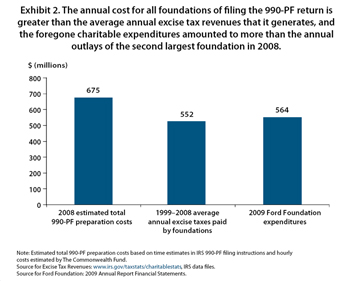

If the 990-PF is a necessary requirement of private foundations, it is also a costly one: estimated total filing costs in 2008 for all foundations was $675 million (Exhibit 2).3 To put this number in perspective, it is the equivalent of the required payout for charitable purposes of a perpetual foundation with $13 billion in assets. Such a foundation would be the second largest, falling somewhere in between the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Ford Foundation. Further, combined 990-PF preparation costs are greater than the $552 million in average total annual excise tax receipts generated by the return.4 Clearly, the return should be structured for maximum efficiency so that it can meet its regulatory aims while minimizing forgone charitable expenditures.

As described below, the 990-PF has served its principal purpose of eliminating the abuses in the foundation field that existed prior to 1970 and has helped steer foundations away from inappropriate activities since that time. But it has failed to keep up with the evolution of the foundation sector over the last 40 years. As both an instrument of basic regulation and tax collection and a tool for promoting strong performance among private foundations, the 990-PF is seriously flawed. Its modernization could yield many benefits to the sector and, more important, to the hundreds of thousands of nonprofit organizations that foundations serve.

As described below, the 990-PF has served its principal purpose of eliminating the abuses in the foundation field that existed prior to 1970 and has helped steer foundations away from inappropriate activities since that time. But it has failed to keep up with the evolution of the foundation sector over the last 40 years. As both an instrument of basic regulation and tax collection and a tool for promoting strong performance among private foundations, the 990-PF is seriously flawed. Its modernization could yield many benefits to the sector and, more important, to the hundreds of thousands of nonprofit organizations that foundations serve.

This essay traces the history of the 990-PF to reveal how its current structure and content came to be. It then analyzes the return’s shortcomings and discusses how the 990-PF could be transformed into a more effective instrument for promoting accountability and best practices in the foundation sector. Although it will not be possible to implement all of the recommendations, in the debate over reform and simplification of our federal tax code, modernizing Form 990-PF should be given serious consideration.

To read the complete essay, download Modernizing the 990-PF to Advance the Accountability and Performance of Foundations: A Modest Proposal.

1 Foundation Yearbook, 2010 Edition, (New York: The Foundation Center), foundationcenter.org. Data are for 2008.

2 The privately funded and nonprofit Foundation Center maintains the most comprehensive database on U.S. and, increasingly, global grantmakers and their grants and operates

research, education, and training programs to advance knowledge of philanthropy.

3 Based on IRS estimates of average time requirements for different aspects of the filing process, in Internal Revenue Service, 2010 Instructions for Form 990-PF, p. 30, Paperwork Reduction Act Notice. Using the IRS’s time calculations and estimated hourly preparer rates, the average cost of filing the return is $9,000. Costs for individual foundations, of course, vary widely, depending on their size and complexity of operations. With a $650 million endowment, The Commonwealth Fund, for example, spends about $18,000 in preparing its annual tax return. The author thanks Commonwealth Fund controller Jeffry Haber for these estimates and for his other contributions to this paper.

4 See www.irs.gov/taxstats/charitablestats , IRS data files, average for the 1998–2008 filing years.