This blog post was updated on August 27, 2021.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act creates a state option to extend Medicaid eligibility to the uninsured for COVID-19 diagnostic testing. This special eligibility option is fully funded by the federal government and in effect as long as the nation is operating under a declared public health emergency. This declaration was recently renewed with no end date specified. Given the magnitude of the pandemic, it is likely that the national state of emergency will be in effect for the foreseeable future.

The option covers both diagnostic tests and testing-associated visits. The subsequently passed Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act clarifies the range of tests covered. The Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act, passed by the House in May and now pending in the Senate, would further expand the option to cover treatment and health conditions that could complicate COVID treatment, as well as vaccines.

Medicaid has a long history as a public health “first responder.” The option to cover COVID-19 testing for the uninsured builds on this history. It is groundbreaking for several reasons: it is tied to a public health emergency declaration, connected to a specific diagnosis, and fully funded by the federal government. The legislation also makes clear that this option is not tied to most traditional Medicaid eligibility rules. Specifically, the statute says that “notwithstanding any other provision of this title,” the option extends to individuals who are uninsured; people with short-term plans are defined as uninsured. The option does contain a state residency test; eligibility ends if an individual moves out of state. Otherwise, the law’s express use of “notwithstanding any other provision of this title” means that it overrides other normal eligibility factors such as income, resources, or status as a citizen or long-term legal resident. Historically, Medicaid’s long-standing emergency coverage provision overrides the legal status test; this provision goes further by eliminating other normally applicable rules.

This special treatment makes sense. During a public health emergency involving a highly communicable disease, the only factor that matters — not just to individual people but to entire communities — is rapid access to testing and treatment.

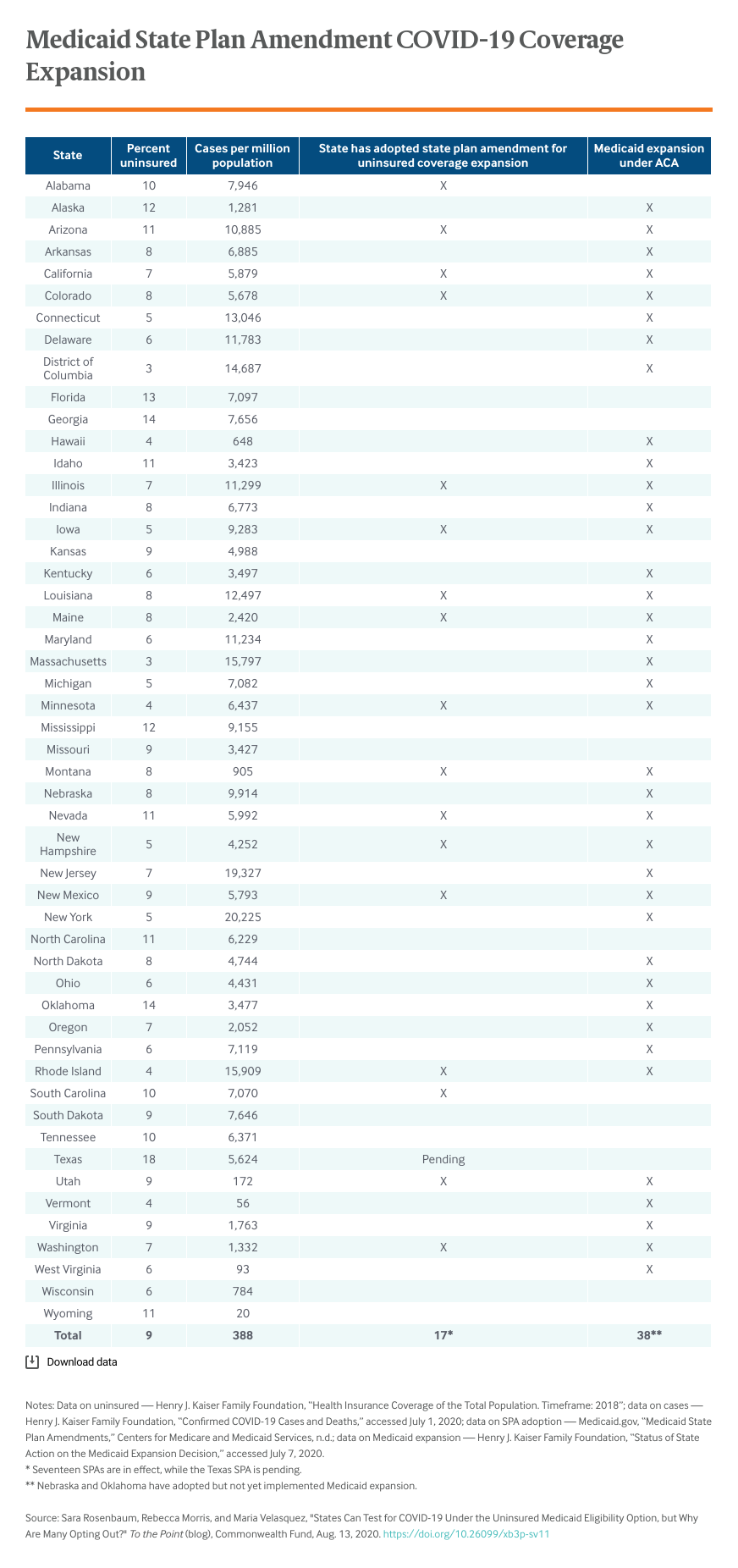

As of the end of July, 18 states had added this eligibility option to their state plans. The majority of these — 16 of 18 — are states that have already shown a commitment to getting people insured by expanding Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

A number of factors may be propelling these low adoption rates. For one, the uninsured testing eligibility option is temporary; despite what is likely to be a lengthy state of emergency, some states may prefer to use emergency appropriation funding rather than set up a new Medicaid eligibility system until grant funding is exhausted. And yet, states are accustomed to short-term Medicaid plan modifications, especially during emergencies. During this pandemic, virtually all states have taken advantage of special HHS emergency powers to modify one or more Medicaid provider payment and participation rules for the duration of the declared emergency.

Another reason may be that the eligibility option covers diagnostic testing only; state adoption may increase if Congress ultimately expands the option to include treatment, as in the HEROES Act.

Yet another explanation may be the work burden that state Medicaid agencies now face in light of an enrollment surge. As noted, states are already pursuing a host of other emergency program modifications, such as adjusting provider payments, adding benefits and covered care settings, and revising managed care contracts to enable plans to better address pandemic-related health needs.

Another factor may be that states are choosing to rely on the emergency funding Congress has appropriated directly to health care providers and governments. This includes grants to states or a special Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)–administered COVID-19 Uninsured Claims Reimbursement Fund or the HHS Provider Relief Fund. Little is known about the Uninsured Claims Fund or claims paid to date, but according to HRSA, payments are “generally” paid at the Medicare rate. Thus, this funding source may be preferable to the extent that Medicare rates exceed those payable under state Medicaid programs. But it is unclear when this fund will run out or whether it will be replenished.

Finally, the Trump administration’s implementation of the eligibility option may be playing a part. Despite the law’s explicit language, CMS guidelines specify that states must “collect contact information, applicant Social Security number, [and] attestation of citizenship/immigration status.” Further, CMS requires states to collect a full declaration of legal status from applicants. These requirements are at odds with the plain language of the law and may be adding to states’ reluctance to adopt the option. CMS’s policy cannot be squared with Medicaid’s traditional policies where emergency care is concerned.

The COVID-19 pandemic is surely an emergency, especially given its disproportionate impact in the poorest communities where immigrants — who may likely be uninsured —tend to reside. Even the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has exempted Medicaid enrollment for COVID treatment from its rules that otherwise allow the agency to bar green card status for legal residents who use most forms of Medicaid. CMS’s policy contradicts not only the law but the pressing nature of the need.

Controlling the pandemic relies on testing. With appropriations beginning to run out, the Medicaid uninsured option presents an important element in state’s approaches to testing and public health.