Introduction

For nearly two decades, the Commonwealth Fund has tracked health and health care in each state, seeking both to understand how the policy choices we make affect people’s health outcomes and to motivate the change needed to improve the health of all communities across the United States. But assessing how well a state performs on average can mask the profound inequities that many people experience.

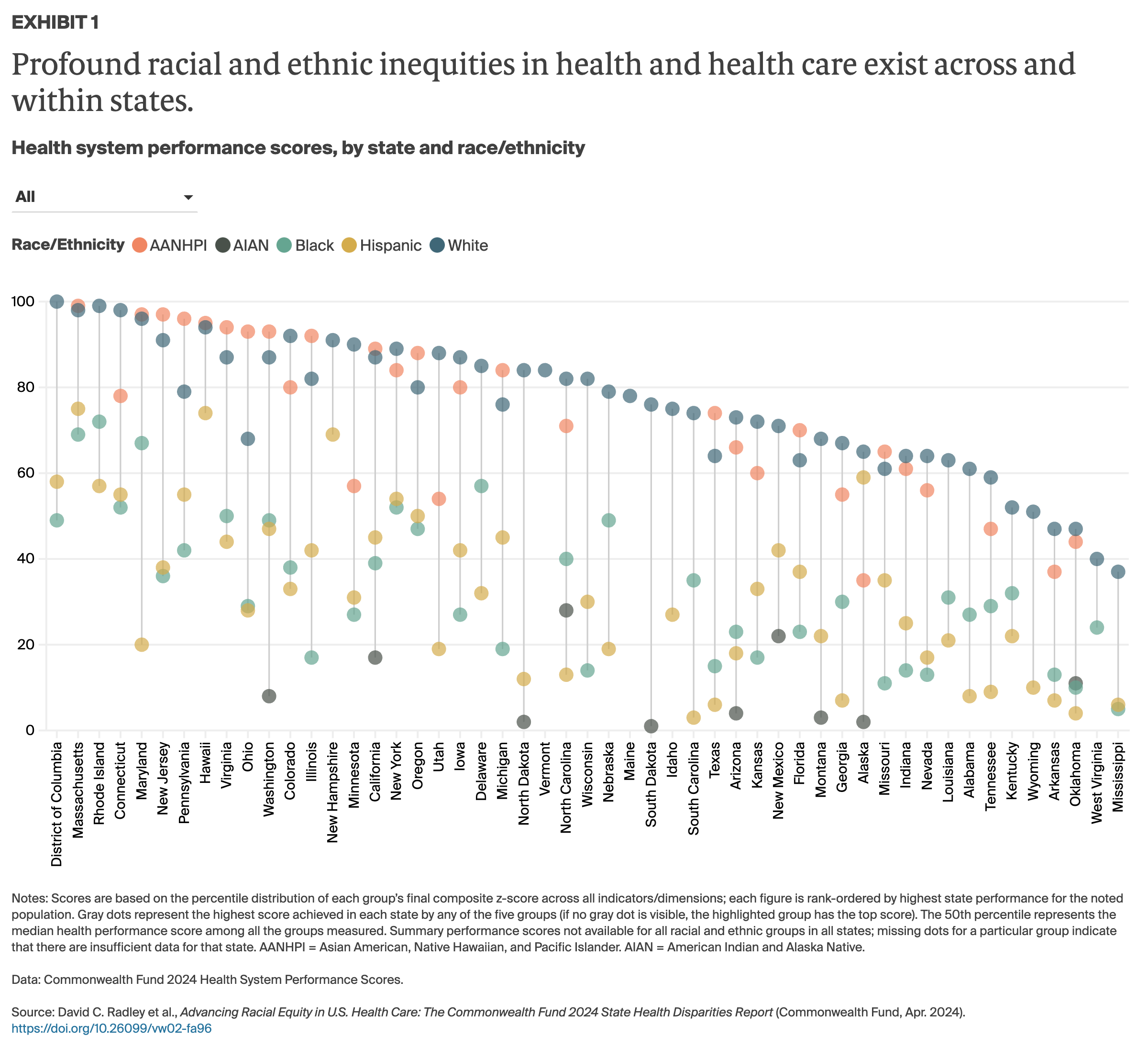

This report evaluates disparities in health and health care across racial and ethnic groups, both within states and between U.S. states. We collected data for 25 indicators of health system performance, specifically focusing on health outcomes, access to health care, and quality and use of health care services for Black, white, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (AANHPI) populations. We then produced a health system performance “score” for each of the five racial and ethnic groups in every state where we were able to make direct comparisons between those groups and between groups in other states. (For complete details on our methods, see How We Measure Performance of States’ Health Care Systems for Racial and Ethnic Groups.)

Our hope is that policymakers, health system leaders, and community stakeholders will use this tool to investigate the impact of current and past health policies on different racial and ethnic groups and to take steps to ensure an equitable health care system for the future.

Overview of Health Disparities in the United States

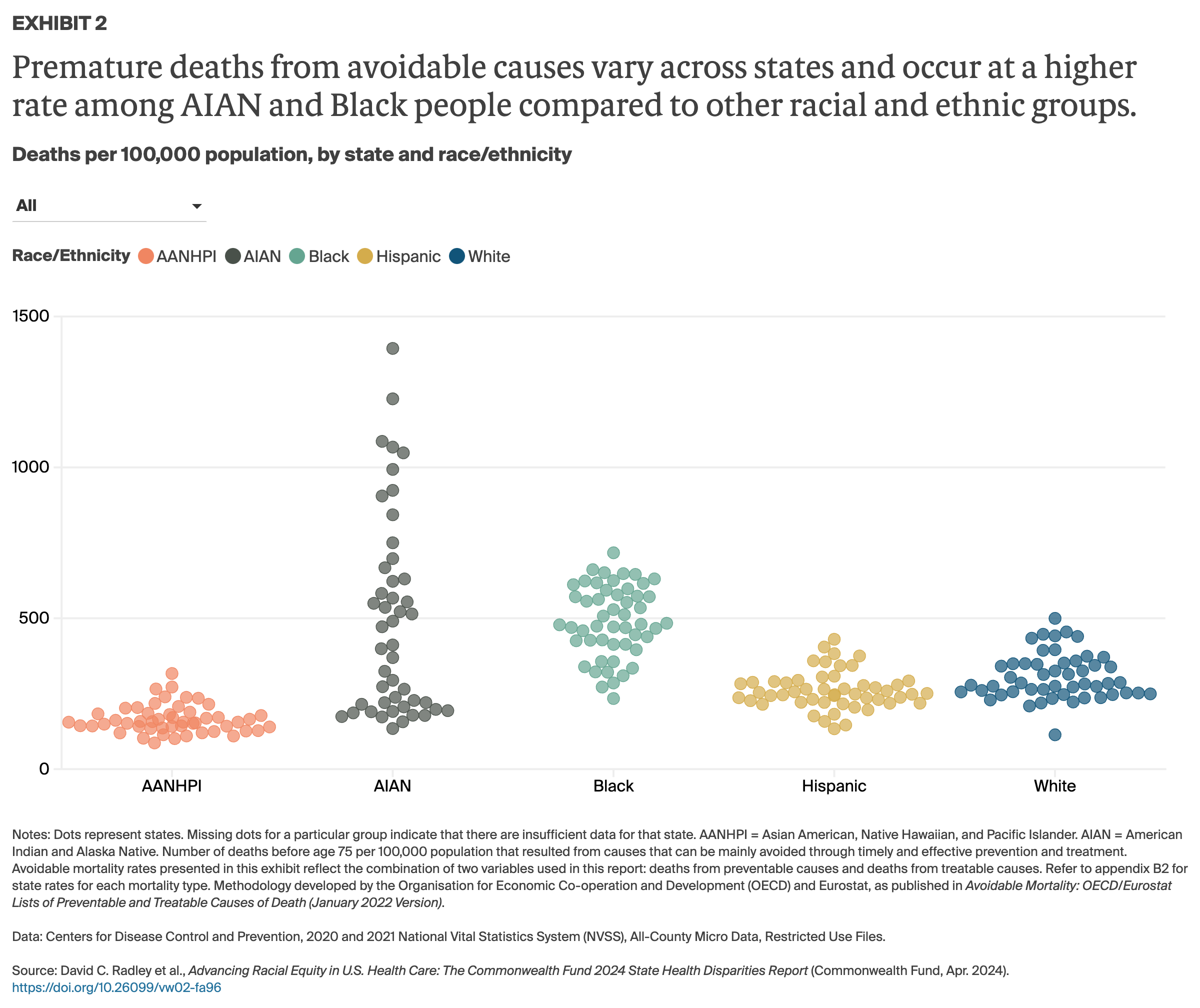

Profound racial and ethnic disparities in health, well-being, and life expectancy have long been the norm in the United States. These disparities are especially stark for Black and AIAN people, who live fewer years, on average, than white and Hispanic people1 and are more likely to die from treatable conditions, more likely to die during or after pregnancy and suffer serious pregnancy-related complications, more likely to lose children in infancy,2 and are at higher risk for many chronic health conditions, from diabetes to hypertension.3

The COVID-19 pandemic only made things worse. Its disproportionate impact on Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people caused a sharper decline in average life expectancy since 2020 for these groups compared to white people.4

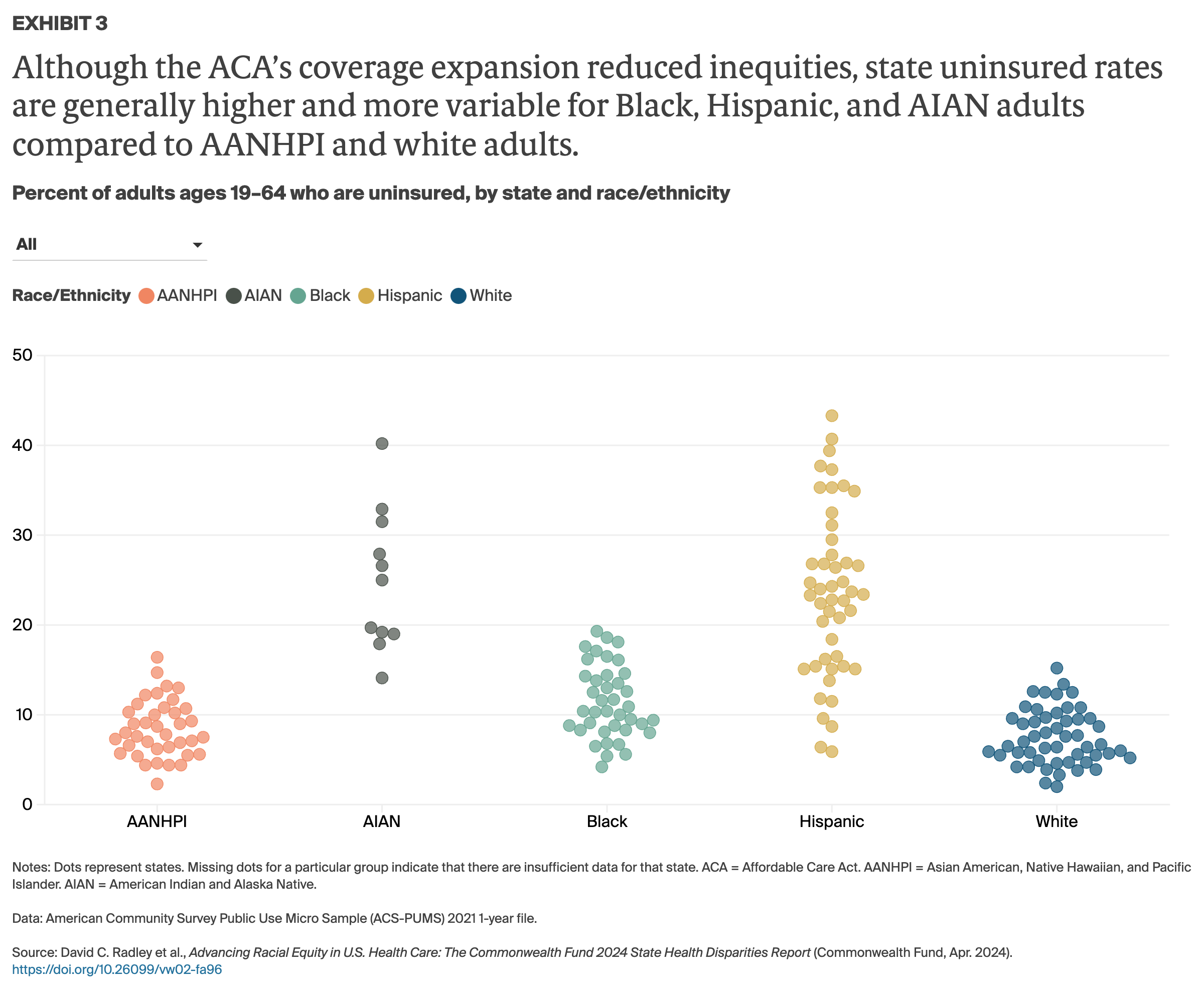

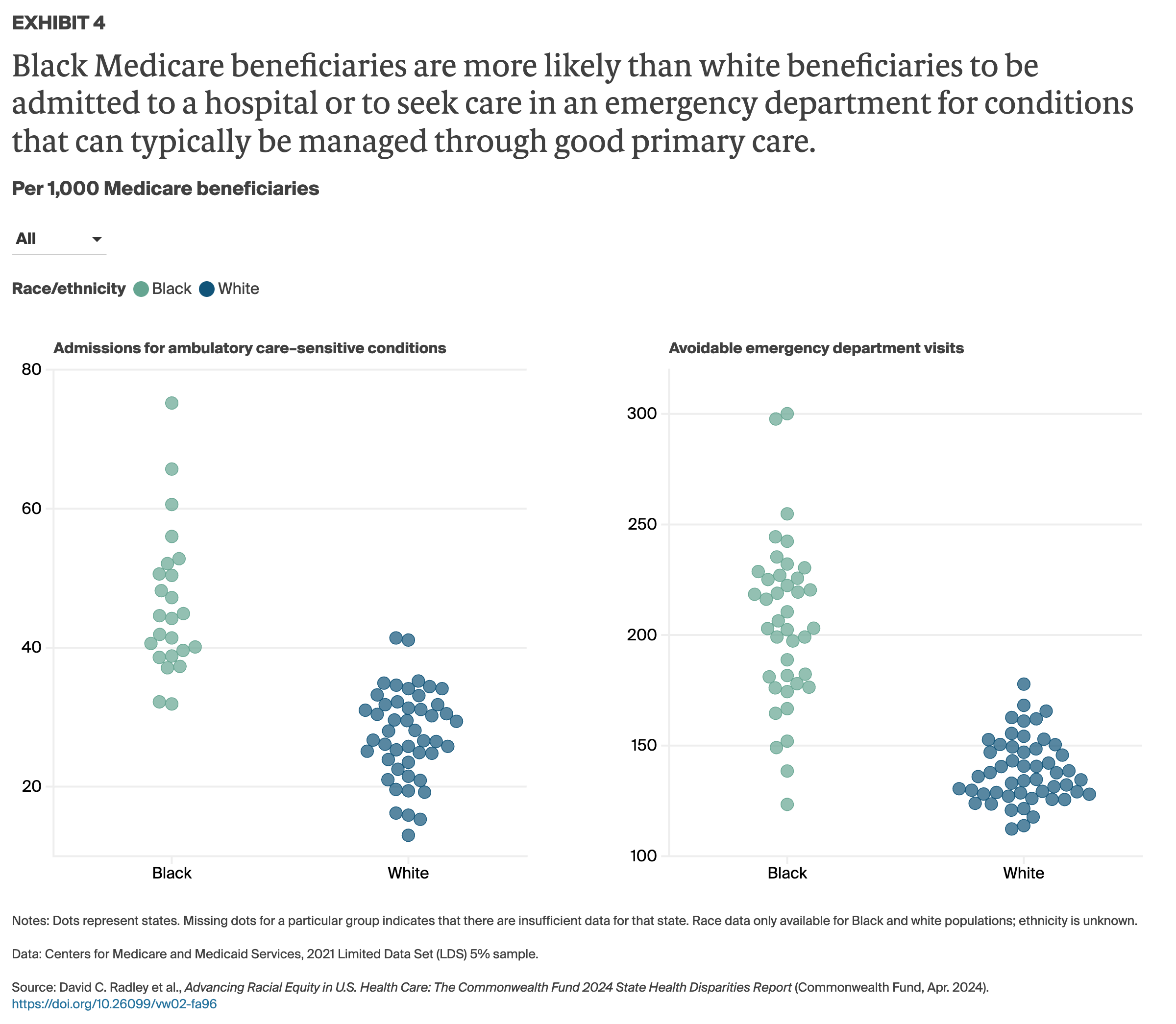

Factors contributing to health disparities. Deep racial and ethnic disparities in health are driven by factors inside and outside state health care systems. For example, in many communities where people of color live, poverty rates are higher than average, levels of pollution and crime are elevated, and green spaces are few — all key contributors to health disparities.5 A lack of affordable, quality health care options, meanwhile, can make it difficult to get timely treatment — a barrier that people of color disproportionately face. Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people are also less likely than other groups to have health insurance, more likely to delay care because of costs, and more likely to incur medical debt.6 And they are less likely to have a usual source of care or to regularly receive timely preventive services like vaccinations.7

Studies show as well that many people of color contend with interpersonal racism and discrimination in health care settings and more often receive worse medical care than white patients.8 According to an assessment by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Black patients received worse care than white patients on 52 percent of quality measures in 2023.9 The study also found marked disparities in quality of care and patient safety with respect to heart disease, cancer, stroke,10 maternal health outcomes,11 pain management,12 and surgery.13

The policy choices that federal, state, and local leaders have made over many decades have led to economic suppression, unequal educational access, and widespread housing segregation, all of which have contributed in their own ways to worse health outcomes for people of color.14 While the nation’s steady and slow progress toward universal, comprehensive coverage has narrowed racial and ethnic disparities in coverage and access to care, it has not eliminated them. In particular, the 10 states that have yet to expand eligibility for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), have the largest coverage gaps by race and ethnicity.