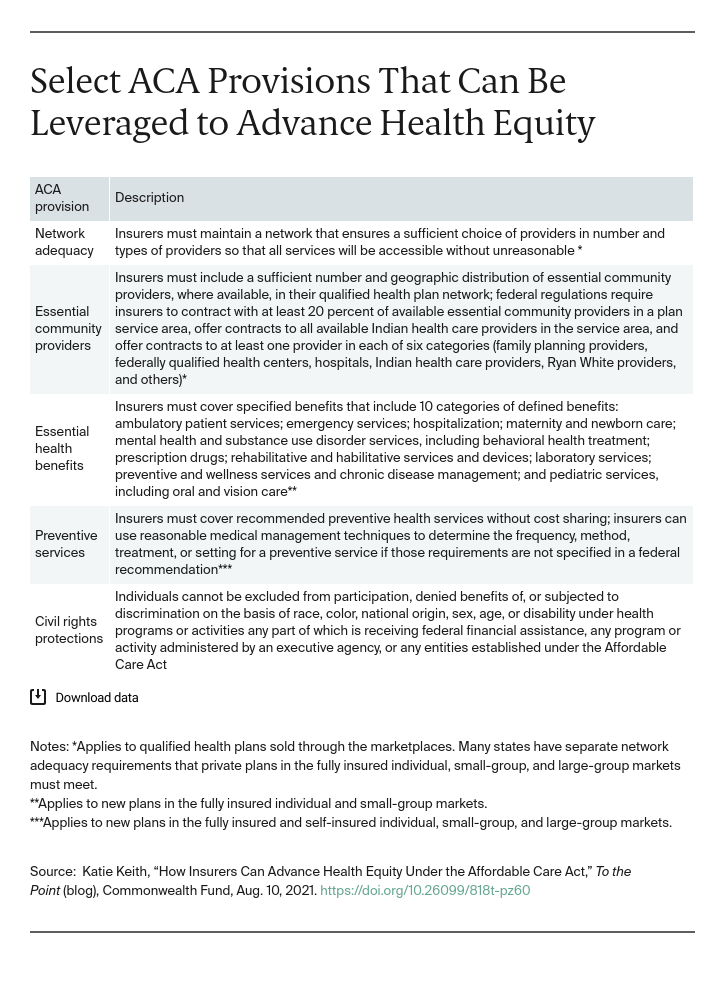

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes many requirements that advance health equity in the commercial coverage market and has contributed to significant progress in narrowing racial and ethnic health disparities. While health insurers alone cannot close disparities, insurance stakeholders play a key role and have committed to doing more to address systemic racism.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners and the American Academy of Actuaries created new committees on health equity while AHIP and Blue Cross Blue Shield Association have pledged to reduce disparities. Yet, to date, insurers have focused primarily on philanthropy and social needs over systemic policies that better serve people of color.

This post highlights several ACA requirements that have not been fully utilized by insurers — resulting in gaps that exacerbate disparities. Insurers and regulators can do more to turn commitment into action.

Provider Contracting and Network Design

The ACA requires marketplace plans to have an adequate provider network and contract with essential community providers (ECPs). Consistent with these requirements, insurers can develop provider networks that better reflect the needs of enrollees of color, as well as other underserved communities such as LGBTQ people and people with disabilities, who often lack access to culturally competent providers and face bias and discrimination in health care settings.

Take, for instance, maternal health disparities for Black and Indigenous people. Insurers could better ensure culturally competent and thus safer care by including a broader range of providers and perinatal workers — such as midwives and doulas — in plan networks. But many insurers do not, even though the services provided by these workers are linked to better outcomes and the ACA requires plans to have an adequate provider network.

Insurers also could do more to meet or exceed weak federal regulatory standards for contracting with ECPs that serve predominantly low-income, medically underserved individuals. These trusted providers, which include federally qualified health centers and Indian health care providers, have a long history of serving people of color. Many provide specific services that help improve care, like translation and interpretation; benefits that may historically carry stigma, such as HIV/AIDS treatment; and coordination of social services. Their critical role in serving people of color has been especially visible during COVID-19 vaccination efforts. Despite ACA requirements, not all insurers contract with a full range of ECPs.

In addition, insurers can help ensure that all providers in their networks are trained to serve diverse enrollees and can deliver care to those with limited English proficiency. Without these actions, regulators should consider whether plan networks are truly adequate under the ACA.

Benefit Design

Under the ACA, most plans must cover preventive services — such as tobacco cessation — without cost sharing. This has already reduced some racial and ethnic disparities in access to preventive care. But insurers can do more to increase utilization by eliminating remaining financial barriers to care.

Consider the coverage of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a medication that prevents the transmission of HIV in high-risk populations (e.g., gay and bisexual men of color). Insurers were required to cover PrEP without cost sharing beginning in 2021, but not all extended cost-sharing protections to the ancillary services needed for a PrEP regimen, like regular labs and provider visits. People who use PrEP had to pay out-of-pocket for these services. These higher costs led, in turn, to lower utilization of PrEP. By extending cost-sharing protections to ancillary services, insurers could have eliminated this cost barrier and made it easier to access this lifesaving care. Instead, federal officials stepped in to clarify that insurers must cover these services and office visits without cost sharing. Insurers could similarly broaden cost-sharing protections to increase access to other preventive services where disparities (and financial barriers) continue to exist, such as colorectal cancer screening.