An unexpected outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic is the immense progress the U.S. has made in expanding health insurance coverage. More people are insured now than ever before thanks in large part to the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) of 2020. Passed by a bipartisan Congress, the law, among other provisions, provided states with enhanced federal matching funds if they agreed to keep people continuously enrolled in Medicaid through the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). All states — both Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states — accepted the match. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that this provision has increased Medicaid enrollment by nearly 13 million people.

But these gains will dissipate when the PHE ends, likely in 2023, when regular Medicaid operations resume. Under Medicaid rules, states must assess whether those currently enrolled remain eligible, a process that could trigger disenrollment for up to 16 million people.

Now is an opportune time for Congress to apply the lessons of the pandemic and make it easier for states to keep those who remain eligible for Medicaid enrolled for longer periods of time.

Why did the continuous enrollment requirement drive enrollment so much higher than in prior years?

In the absence of FFCRA, existing state and federal policies make it hard for eligible people to stay enrolled in Medicaid. People become eligible for Medicaid because of their income or need for health care services, like being pregnant or having a disability. Under federal law, states must verify that Medicaid enrollees remain eligible for coverage at least once a year. But throughout the year, enrollees are required to report income fluctuations that may affect their eligibility and many states conduct periodic checks on income and other criteria. Even small bumps in people’s income, such as from seasonal work, can trigger disenrollment, even though their income might fall in a few months and make them eligible again.

Consequently, the average length of enrollment in Medicaid before the pandemic was less than 10 months. Many people are disenrolled only to reenroll when their income drops or they secure necessary documents to prove eligibility. Most don’t immediately find other coverage. One study found that among people who lost Medicaid over a two-year period, three-quarters became uninsured for part or all of the remaining time period and nearly one-quarter regained Medicaid coverage.

Does continuous enrollment in Medicaid make a difference in terms of access to care and financial protection?

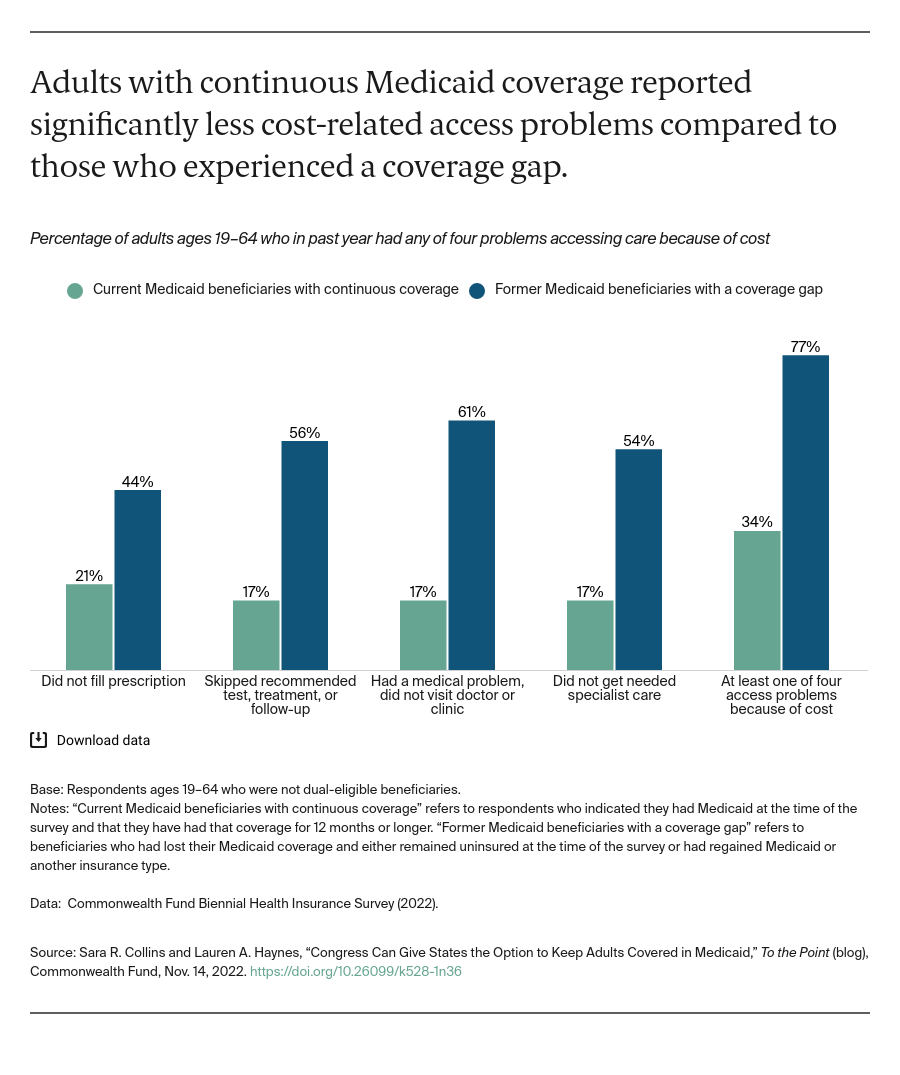

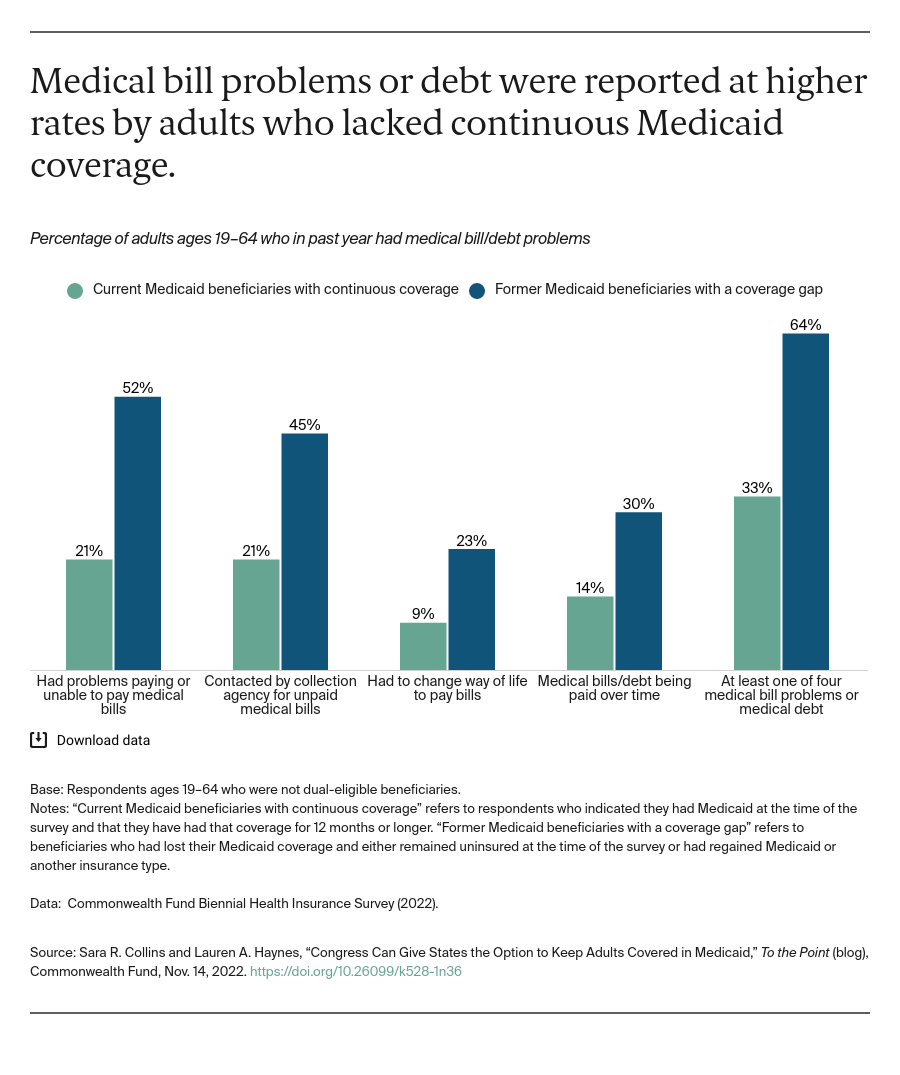

Yes, a dramatic difference. New data from the 2022 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey finds stark differences in the health care experiences of people with continuous Medicaid coverage compared with those who had lost their coverage and either remained uninsured at the time of the survey or had regained insurance, either Medicaid or another type. Those who had lost their Medicaid coverage and had a coverage gap reported delaying or skipping needed health care or prescriptions because of cost at more than two times the rate of adults who had Medicaid continuously for the prior 12 months (77% vs. 34%).