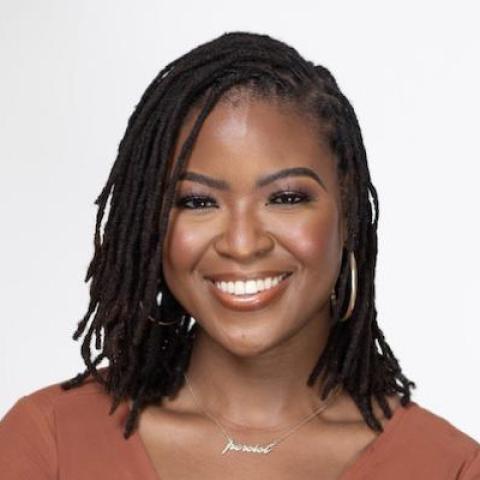

Daphne, a young Black woman from a highly segregated, low-income neighborhood in New York, was insured through Medicaid for much of her life. In an interview conducted several years ago, Daphne was asked whether Medicaid beneficiaries had the power to change the health system. She said:

I don’t know if they do have any power to change it, but I believe they would like to change things . . . . But I just think a lot of people . . . they have jobs . . . some people work like two to three jobs just to make ends meet so I don’t even think they have time . . . . I know our population deal with mass incarceration, so even that too. So, I feel like sometimes the system, it’s made for us to stay down.

Daphne incisively underscored structural barriers preventing Medicaid beneficiaries from influencing systems that acutely affect their lives and communities. In recent research that included conversations with more than 200 Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries, we found such sentiments were common. Participants echoed each other, captured succinctly by an interviewee in Kentucky: “Our voice don’t really get heard.”

Voice is key for advancing equity. It is a central consideration in the Racial Equity and Policy (REAP) framework — a tool used for assessing racial equity in developing, implementing, and evaluating policy. This blog post focuses on the logic and process of incorporating voice to support racially equitable policymaking.

Voice, Equity, and Power

Racial and class marginalization hinders people’s ability to exercise adequate control over outcomes that profoundly shape their lives. Americans racialized as White as well as wealthy Americans are better represented politically and have a disproportionate capacity to shape policy agendas. Such power imbalances have concrete consequences in arenas ranging from housing to health care to wages. Marginalized communities must have their voices robustly centered in policy processes to achieve more equitable outcomes.

Incorporating voice into policy requires systematically including the perspectives and experiences of oppressed groups most affected by the policy. Voices within racially and economically marginalized communities can be expressed in numerous ways, including but not limited to: voting, protest, community organizing, participation on boards or committees, submission of formal comments, and through qualitative research. Maximizing the inclusion of voice requires careful thinking about the implications of these different modes of participation, including grappling with the salience of some and the absence of others.

Policy processes are more equitable when marginalized voices guide them. For example, tenants and tenant organizations in poor Black and brown communities have spearheaded policies expanding civil legal rights and securing equitable housing. Similarly, when people living with serious mental illness were included in qualitative research, they had the power and platform to inform policy by describing how mental health programs operated.

How to Center Voice in the Policymaking Process

Even well-intentioned actors can leverage voice in ways that are tokenistic, paternalistic, exploitative, and disempowering. We offer five concrete recommendations on how to center the voices of racially marginalized people.

- Share power. To engage voice, power must be shared appropriately among analysts, academics, public officials, and the people most affected by policies. Centering voice requires recognizing and righting power imbalances.

- Build power. Including voice requires resources — time, money, attention — to build power among racially marginalized groups. This helps to ensure that people who currently hold disproportionate power do not exploit racially marginalized groups in the name of “voice.” To prevent this kind of exploitation and build power equitably, in 2022, legislators in Washington State proposed a bill that aims to “increase the participation of impacted communities by allowing agencies, boards, and commissions to compensate low-income and underrepresented community members” for their participation. It includes a stipend of up to $200 per day as well as expenses to cover travel, lodging, and child or elder care.

- Differentiate voice. Incorporating voice does not mean homogenizing or flattening differences within marginalized groups. Instead of selecting a singular “representative” who speaks for all people within a group, heterogenous and intersecting voices should be encouraged and acknowledged.

- Institutionalize voice. Centering voice in policy processes must go beyond discrete, one-time efforts. Instead, the goal should be to create enduring pathways through which voice will be included on an ongoing basis. The state bill in Washington, for instance, provides an enduring institutional channel to support voice.

- Broaden voice. Incorporating voice manifests broadly, throughout various policy phases (e.g., design, proposal, enactment, implementation, evaluation) and across different environments (e.g., in various networks, institutions, contexts). The REAP framework delineates key questions that guide thinking about how to broaden the inclusion of voice into policy processes.