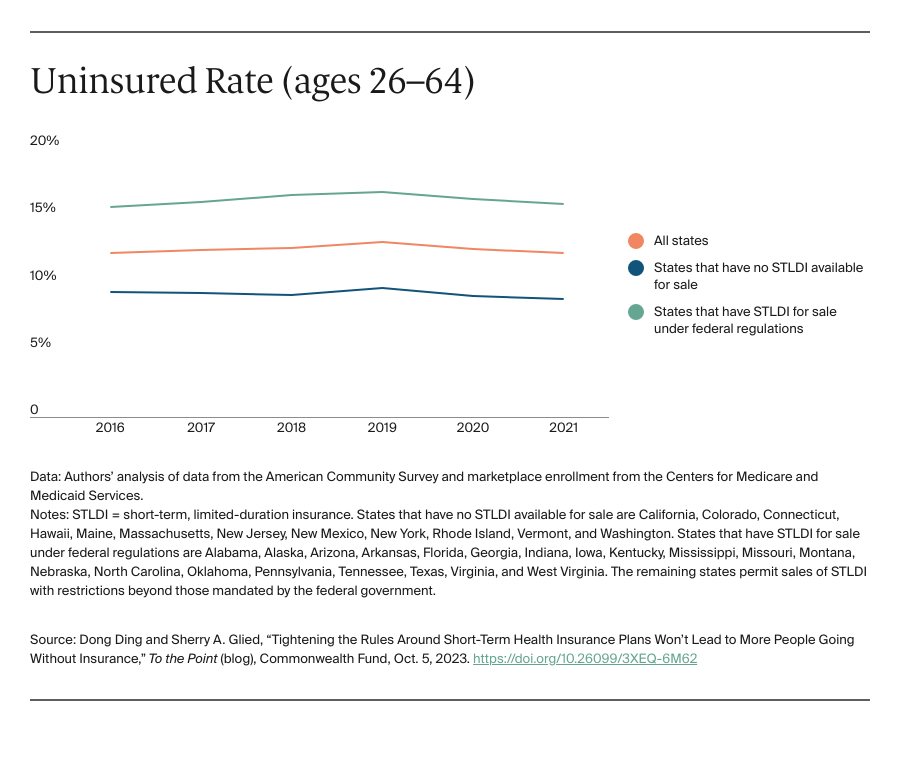

Short-term, limited-duration insurance (STLDI) plans are exempt from the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) essential benefit coverage requirements and from prohibitions on medical underwriting. This means that consumers with preexisting conditions can be denied coverage and anyone who purchases such a plan may lack coverage for key services. In August 2018, under the Trump administration, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services revised the definition of short-term plans to include coverage with an initial term of less than 12 months that could be renewed for up to 36 months. While the purported goal of this change was to increase coverage and reduce uninsured rates, our analysis indicates that it did not accomplish this: coverage did not increase and the uninsured rate did not drop.

In July 2023, the Biden administration issued a notice to limit the initial duration of short-term plans to three months, with an option to renew for one additional month. This change was intended to ensure that people purchasing insurance coverage have meaningful protection and to preserve the preexisting condition protections in the ACA. Critics feared and some cost estimates suggested that tightening the STLDI rules could leave many without any coverage at all. In 2019, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), using its forecast model (data were not yet available), estimated that 1.5 million people would purchase short-term plans and that 500,000 would gain coverage (relative to being uninsured). Our analysis suggests that these forecasts substantially overstated the effects of the rule change; far fewer people enrolled in STLDI plans and the enrollment that did occur was from people moving off marketplace coverage. There is no evidence that the number of uninsured people declined because these plans became available.

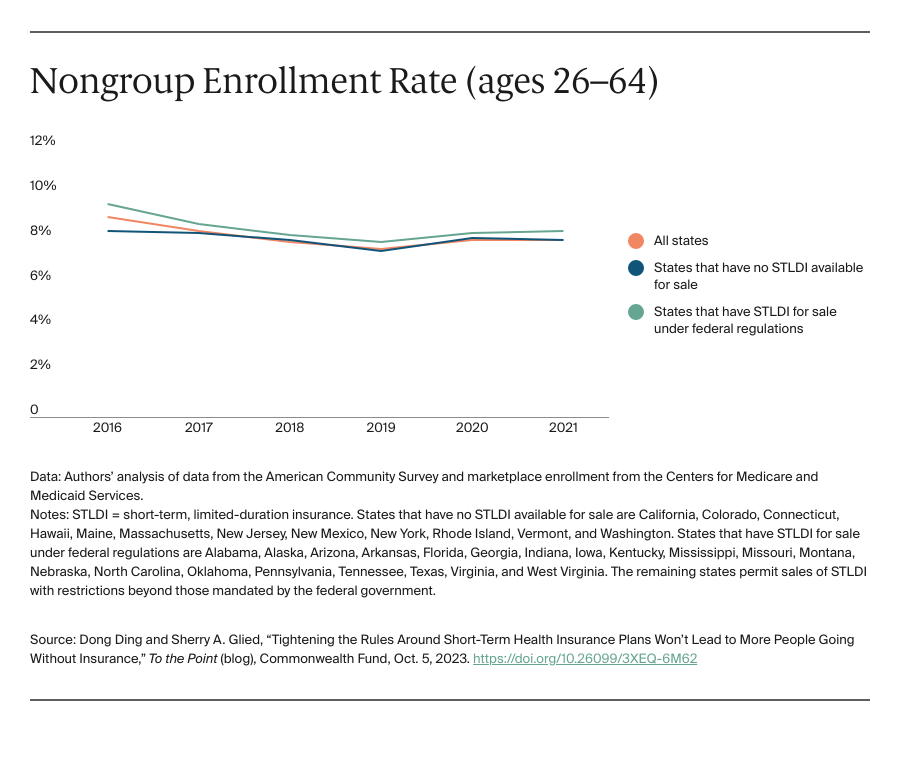

Using data from the American Community Survey and marketplace enrollment from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), we assessed whether the loosening of STLDI regulations (under the Trump administration) led to increased enrollment in off-marketplace nongroup coverage in states that permitted sales compared to those that did not. Plans sold off the marketplace include STLDI as well as ACA-compliant plans, grandfathered coverage, health care sharing ministries, and fixed indemnity plans. Next, we looked to see whether the Trump-era regulations increased nongroup insurance coverage altogether (including marketplace coverage) in these states. Finally, we looked to see whether the broader availability of STLDI was associated with lower uninsured rates. We examined coverage patterns for adults ages 26 to 64 and then focused on young men ages 26 to 35, who may be most sensitive to the presence of regulations similar to those in the ACA because they are less likely to have preexisting conditions or to seek comprehensive coverage.

In 2017, 2.6 million adults ages 26 to 64, about 1.6 percent of that population, purchased private nongroup insurance outside the marketplace. By 2020, about 270,000 more people were enrolled in off-marketplace nongroup plans, across all states, than had been in 2017. There was a larger increase in off-marketplace nongroup enrollment among all adults and among young adults (we cannot separate young men in the CMS data) in states that permitted the sale of STLDI coverage, compared to those that prohibited it. This is consistent with the evidence of growth in sales of these plans. Across all states, about 160,000 more young adults, ages 26 to 34, held off-marketplace nongroup coverage in 2020 than in 2017.

The ACS data show that off-marketplace plans largely substituted for marketplace plans in states that permitted the sale of STLDI. Patterns of enrollment in nongroup plans overall were very similar in states with and without STLDI plans available for purchase over this period. While nongroup coverage was consistently more popular in states with no restrictions, between 2017 and 2020 enrollment in nongroup plans declined slightly more in states where STLDI plans were available for purchase than in those where they were not. The same pattern of marginally greater declines held for young men (and young adults) in states where STLDI plans were available.