The Trump administration’s proposed regulations encouraging the sale of health insurance plans that do not comply with Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) benefit requirements or consumer protections could siphon healthy enrollees from the ACA marketplaces, leaving them with a smaller, sicker group of enrollees. The problem could be compounded when the penalty for not having health insurance is eliminated in 2019.

A new Commonwealth Fund report by Kevin Lucia and colleagues at Georgetown University’s Health Policy Institute examines these “alternative coverage arrangements” — including short-term health plans, association plans, and health care sharing ministries — and the actions states have taken to regulate them. The researchers find:

The Trump administration’s push to increase the availability of non-ACA compliant policies poses a significant threat to states’ individual markets and the people who rely on them. Without state action to regulate these coverage arrangements, consumers will face higher premiums, fewer plan options, and a loss of consumer protections.

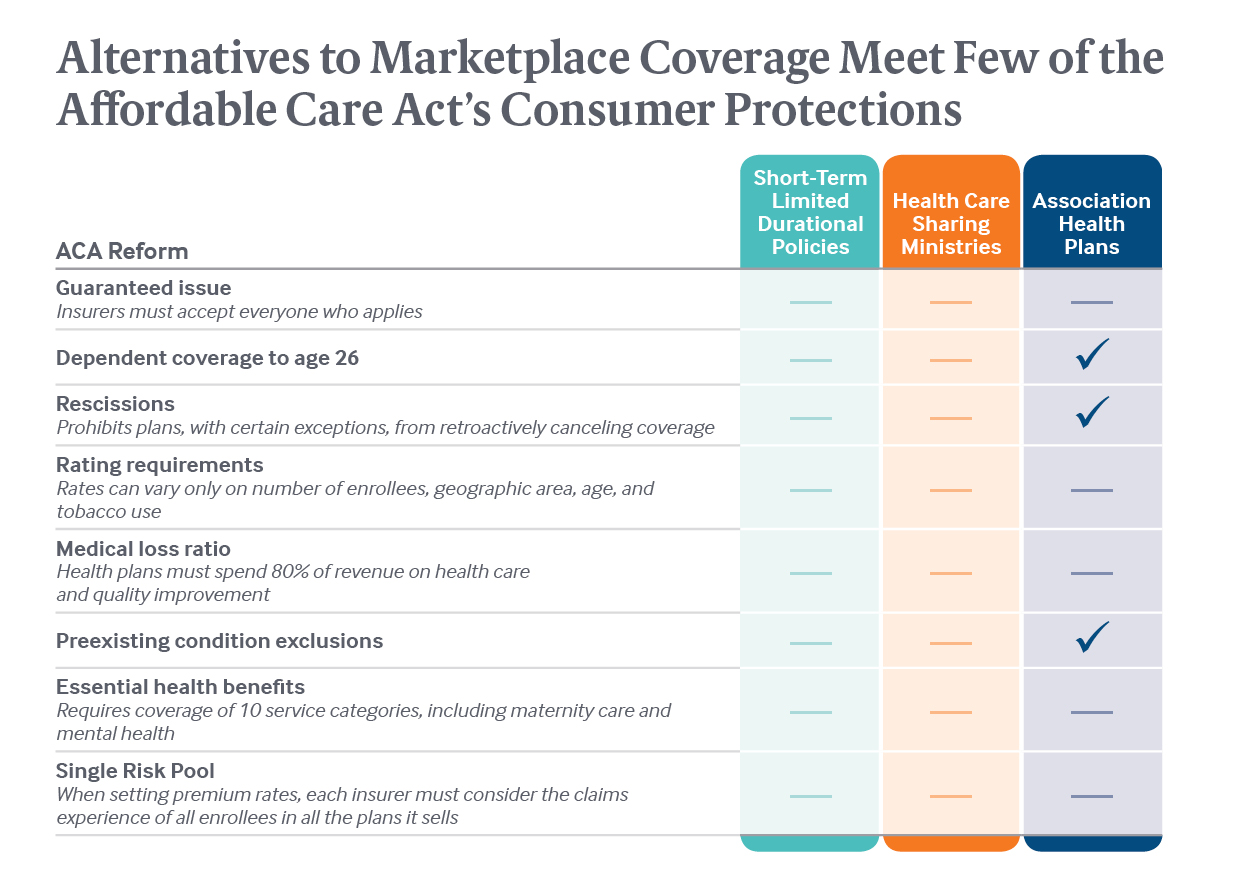

- More consumers will be exposed to financial risk and fraud. Alternative coverage arrangements don’t have to meet many – or, sometimes, any – of the ACA’s federal consumer protections.

- These plans may appeal to healthy consumers because of their low upfront costs. But they often cover fewer services and expose people to high out-of-pocket costs when they get sick. Some of these coverage options also increase consumers’ risk of being defrauded or enrolling in a financially unstable plan.

- Alternative health plans could weaken the ACA marketplaces. The report finds that these cheaper, bare-bones plans would siphon off healthy individuals who would otherwise get coverage in the ACA marketplaces. In turn, risk pools would become smaller and sicker, resulting in higher premiums and fewer plan options for people remaining in the individual market.

- State oversight is weak. Although states have broad authority to regulate alternative-coverage options, most do not – leaving both consumers and their marketplaces at risk.

Additional Report Background

The report outlines the alternative coverage options that could become widely available in 2019, when consumers will no longer face a financial penalty if they choose to go uninsured or purchase coverage that’s not ACA-compliant. These include:

- Short-term plans: Plans designed to fill temporary gaps in coverage. Recent proposed regulations by the Trump administration would allow short-term plans to be extended for up to 12 months and make them easier to renew or extend. Enrollment in short-term plans is projected to expand to more than 4 million people if most states allow these plans to be sold.

- Association health plans (AHPs): AHPs are formed when small businesses and self-employed individuals band together to purchase coverage across state lines. The Trump administration has proposed expanding the availability of these plans, which would be exempt from complying with the consumer protections that otherwise apply to individual plans — including coverage of essential health benefits such as maternity care, mental health services, and prescription drugs.

- Health care sharing ministries (HCSMs): Members of these entities share a common set of religious beliefs and contribute funds to pay for medical expenses of other members. The arrangements are not regulated as insurance under federal law and do not comply with the ACA’s consumer protections, despite their resemblance to traditional insurance. Membership in HCSMs has spiked since the ACA’s enactment, growing from fewer than 200,000 members prior to 2010 to about 1 million currently.

Implications

Thanks to the ACA, more people have health insurance than ever before, and people with health problems can’t be denied coverage or charged more because of their condition. This report shows that some alternative plans could put consumers at risk of inadequate coverage and financial protection, while also leading to instability and higher premiums in the ACA marketplaces.

Although the ACA set a federal benchmark for consumer protections, the law did not limit states’ power to regulate above these minimum standards, the authors of the Commonwealth Fund report say. Nor did the ACA limit states’ capacity to exercise full regulatory authority over health coverage that falls outside the scope of federal insurance law.

Some states have already taken steps to limit the availability of non-ACA-compliant insurance and protect their marketplaces. Massachusetts and New York, for example, have restricted the availability of underwritten short-term policies that don’t meet comprehensive benefit standards, such as coverage for mental health services, prescription drugs, and maternity care. Several other states tightly restrict the duration of such plans.

According to the report, states’ decisions about regulating non-ACA-compliant policies will likely have a significant effect on the accessibility and affordability of individual health insurance and the stability of markets.