Consider a building that’s open all day, every day, with space and staff to accommodate an unknown number of people. The lights are never turned off and operations never cease. The resources needed to always be ready to serve — along with energy-intensive equipment, endemic waste, and a vast supply of goods and services — explain why hospitals and other health care organizations are among the largest energy consumers and greenhouse gas emitters on the planet.

Even among industrialized countries, the U.S. health care system stands out as carbon intensive: it accounts for about a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions from health care activities worldwide, more than any other nation. Its outsized carbon footprint is not, however, reaping better health outcomes. Americans don’t live longer, healthier lives than residents of other high-income countries, and states with higher health care emissions don’t perform better on measures of health care quality and access. Our polluted air and water, along with more severe storms or heat waves, also take a toll on human health. In fact, experts estimate environmental harms caused by the health care industry, including greenhouse gas emissions and toxic air pollutants, cost as many lives as preventable medical errors: 98,000 a year.

Driven by concern for patients, the rising costs of energy and other business expenses, and anticipated government regulations that may soon hold them accountable for reducing their carbon footprints, some health care organizations have been working to become more energy efficient. In 2022, 116 organizations, representing 872 hospitals, signed on to the Biden administration’s Health Sector Climate Pledge, a voluntary effort to achieve a 50 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and net zero emissions by 2050.

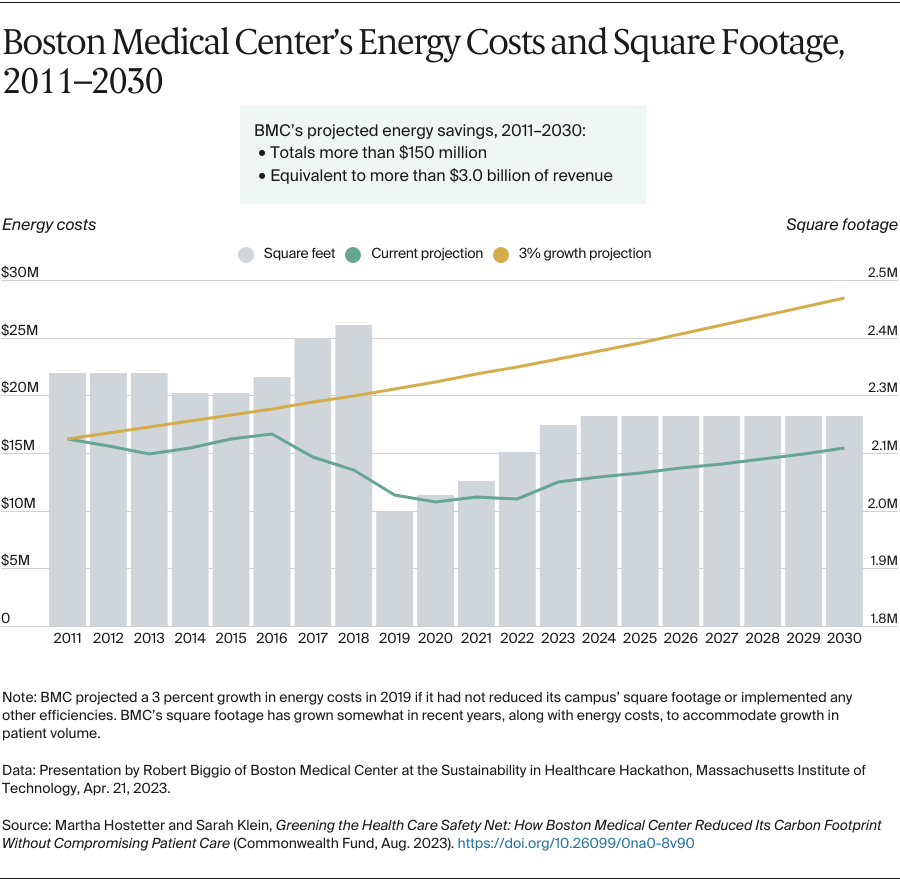

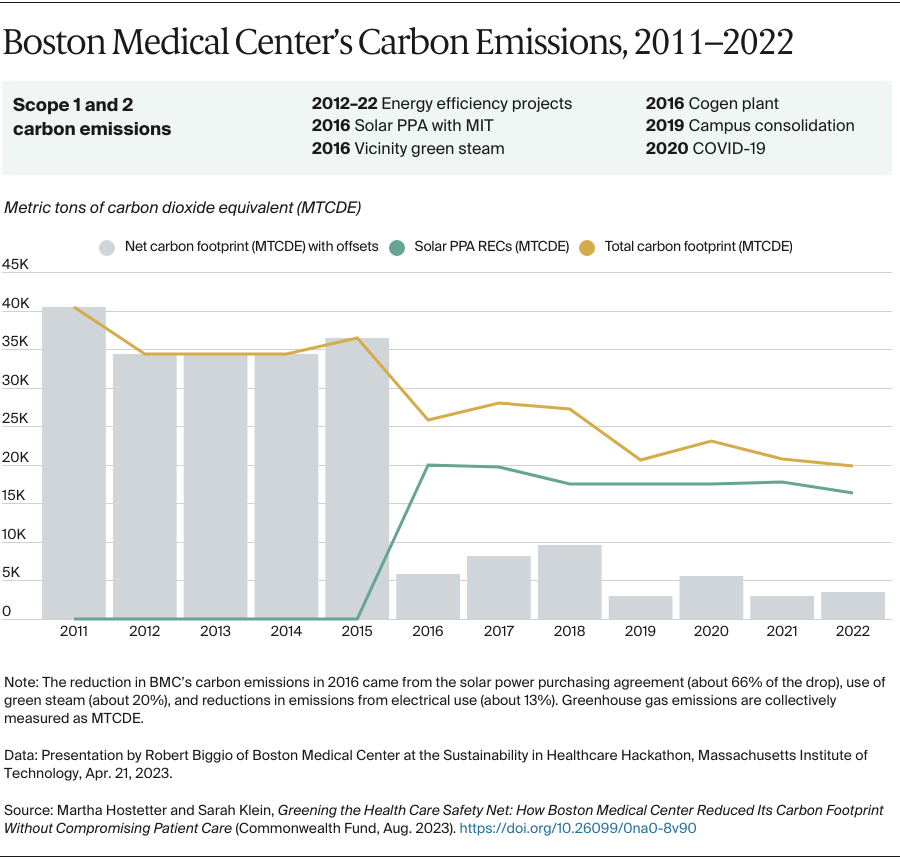

In this case study, we describe Boston Medical Center’s decade-long journey to reduce its carbon footprint. Since 2011, the safety-net system in Boston’s South End has lowered its energy use by about 35 percent and reduced carbon emissions from energy consumption by 91 percent. The health system has done so by shrinking its campus’ square footage, undertaking more than 50 projects to reduce energy use, installing a cogeneration plant, and purchasing solar energy, among other initiatives. This has lowered the health system’s annual operational costs by about $40 million while expanding its capacity to serve patients.