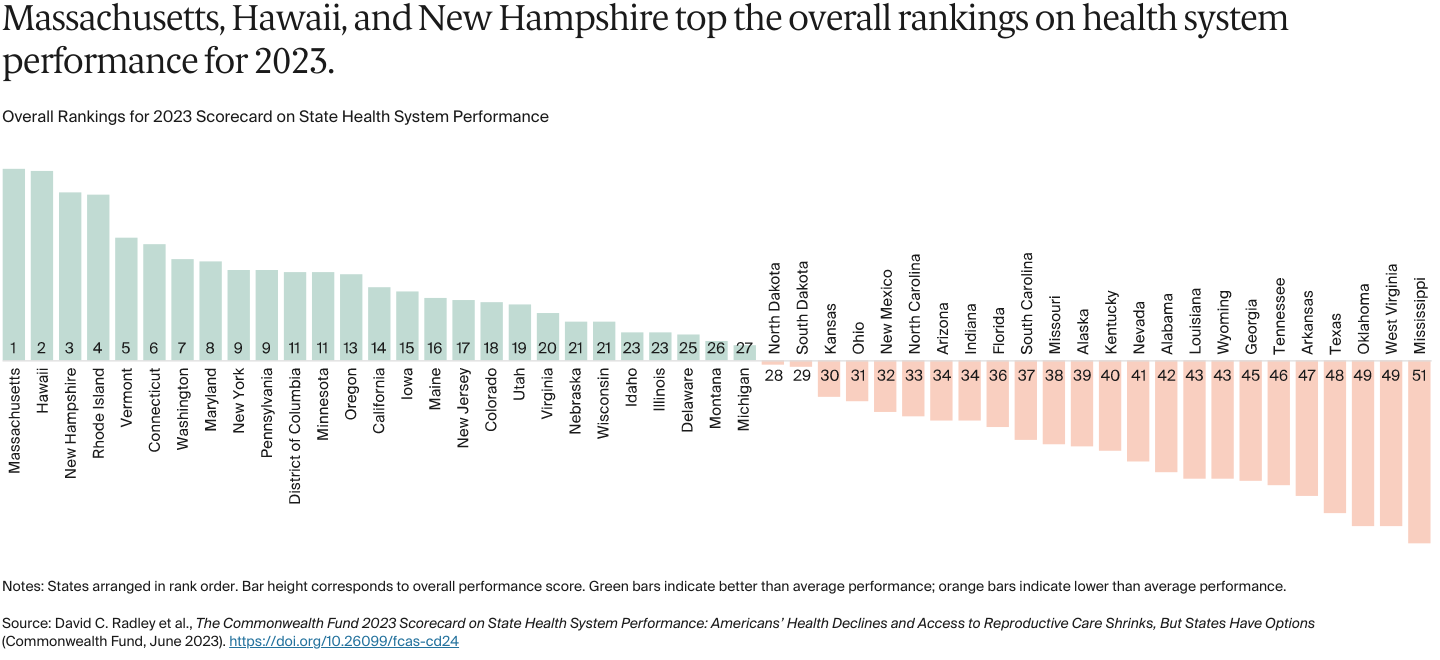

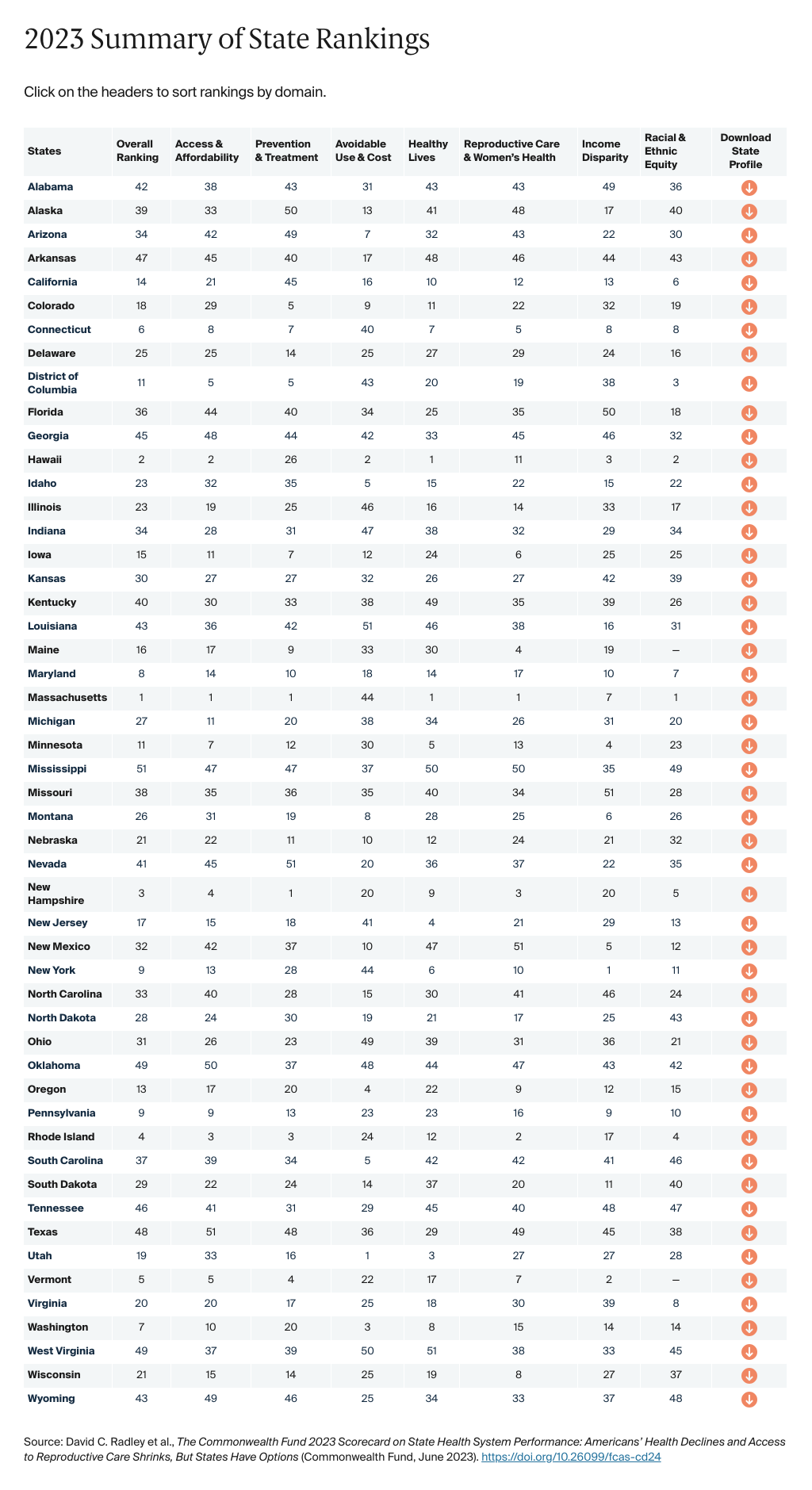

The Commonwealth Fund’s 2023 Scorecard on State Health System Performance evaluates states on 58 performance indicators grouped into five dimensions, including a new dimension focused on Reproductive Care and Women’s Health.

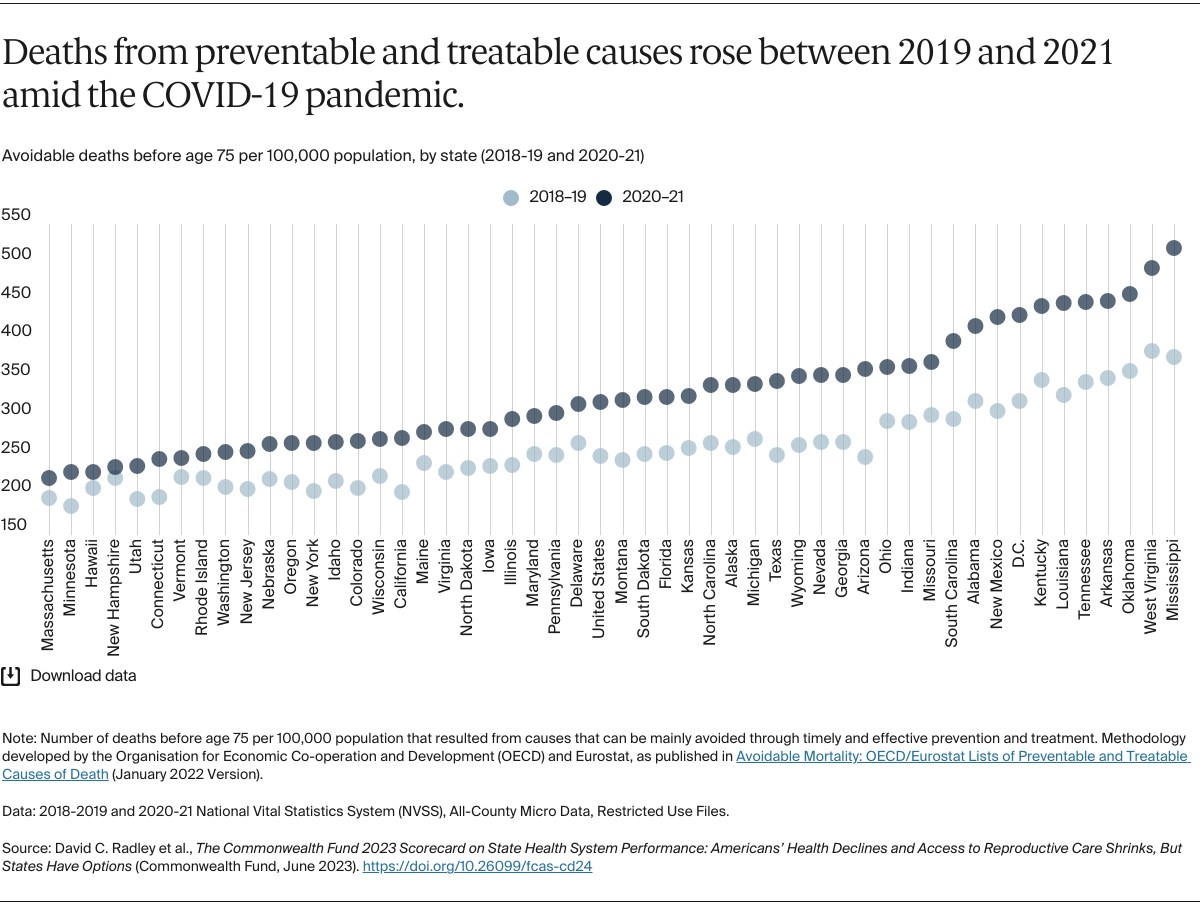

The report generally reflects data from 2021.

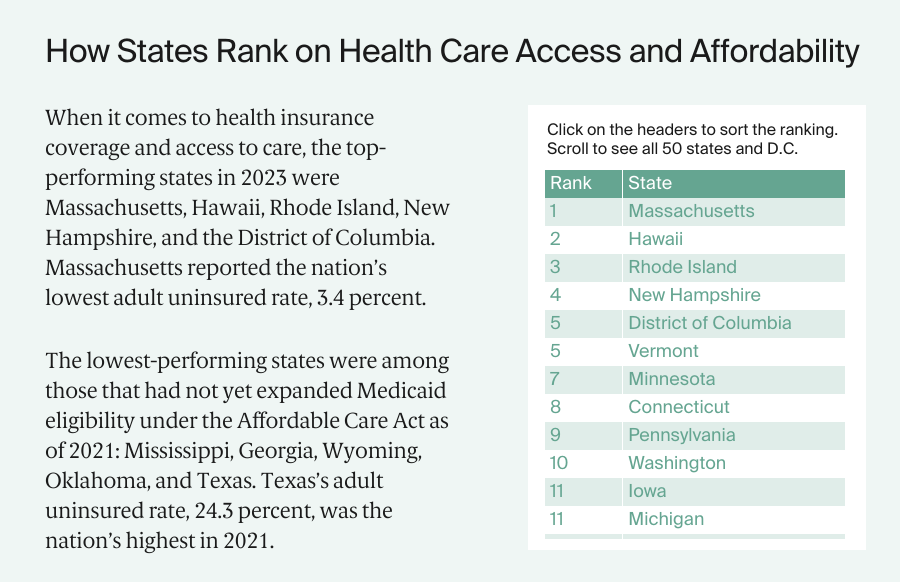

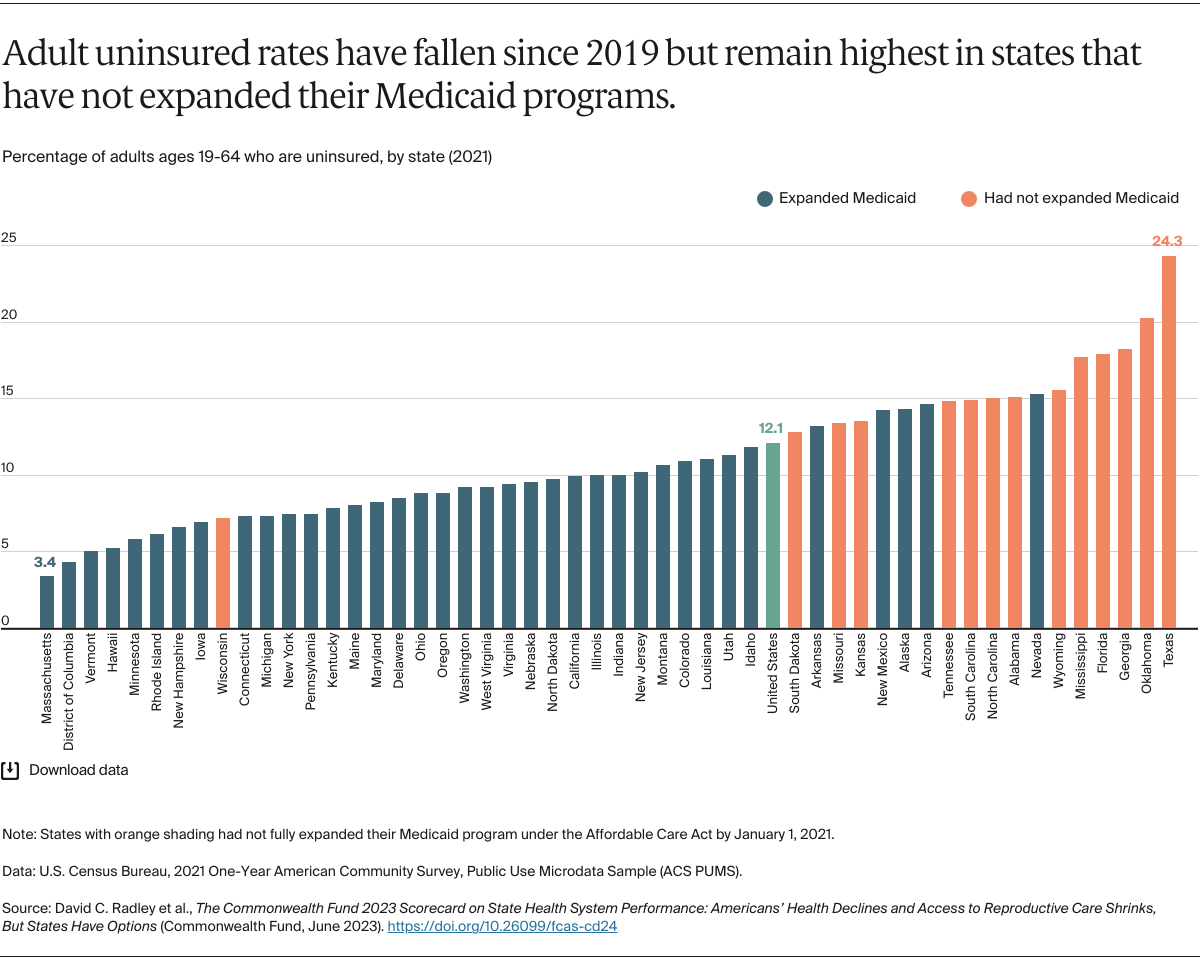

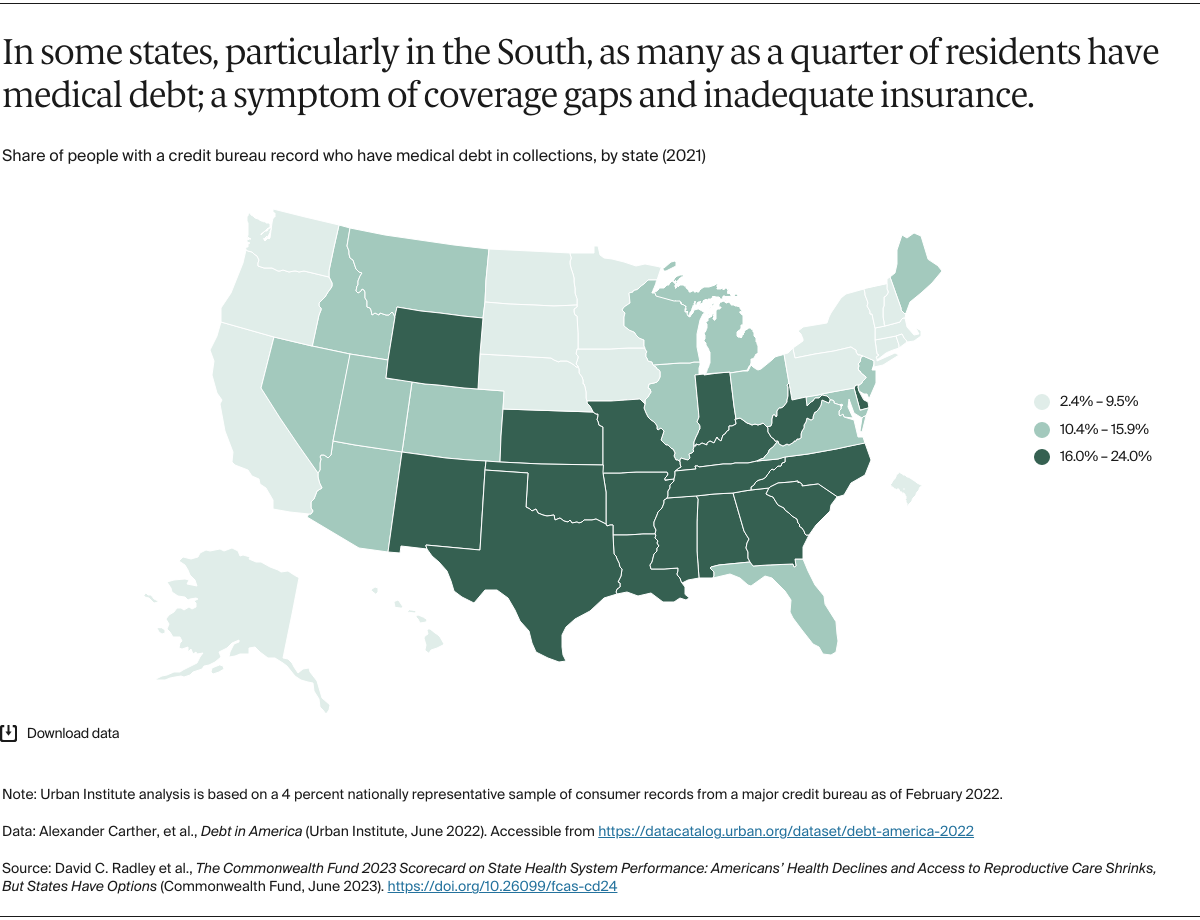

Access and Affordability (8 indicators): includes rates of insurance coverage for children and adults, as well as individuals’ out-of-pocket expenses for health insurance and medical care, cost-related barriers to receiving care, rates of medical debt, and receipt of dental visits.

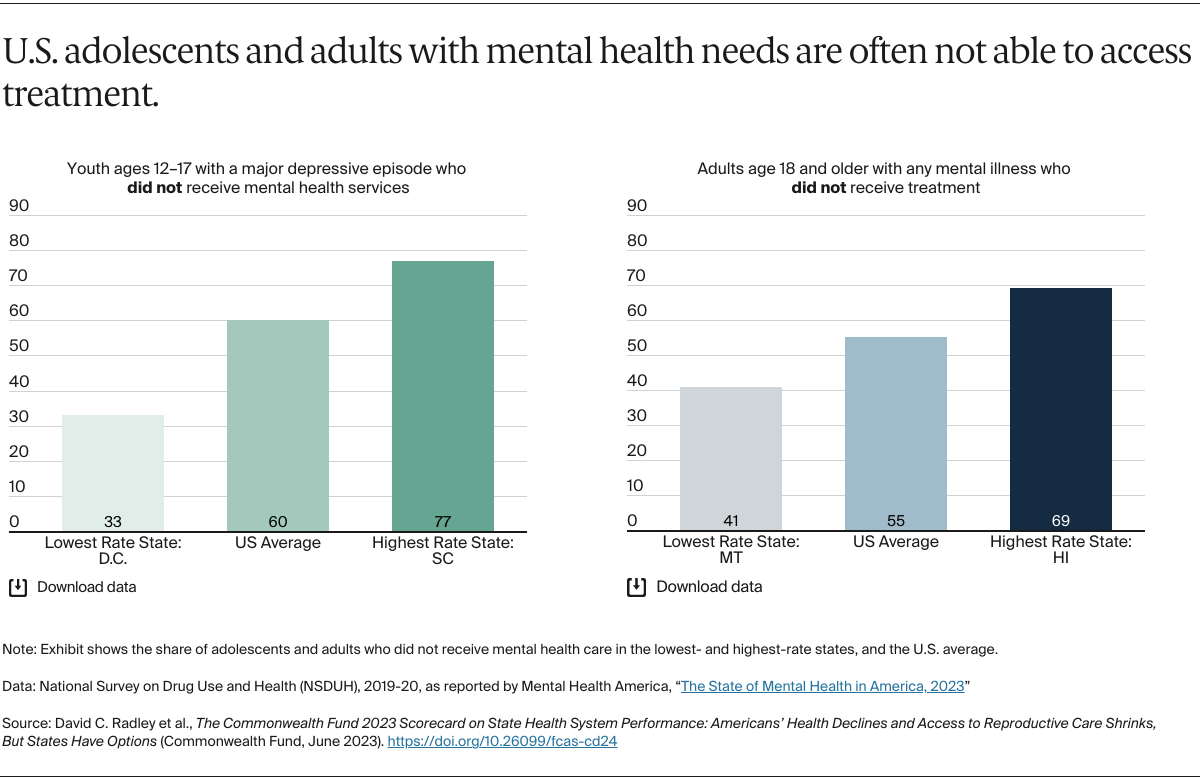

Prevention and Treatment (15 indicators): includes measures of receipt of preventive care (including COVID-19 booster vaccines) and mental health care, as well as measures of quality in ambulatory, hospital, postacute, and long-term care settings.

Potentially Avoidable Hospital Use and Cost (13 indicators, including several measures reported separately for distinct age groups): includes indicators of hospital and emergency department use that might be reduced with timely and effective care and follow-up care, successful discharges for skilled nursing home patients, estimates of per-person spending among Medicare beneficiaries and working-age adults with employer-sponsored insurance, and the share of Medicare and employer-sponsored insurance spending directed toward primary care.

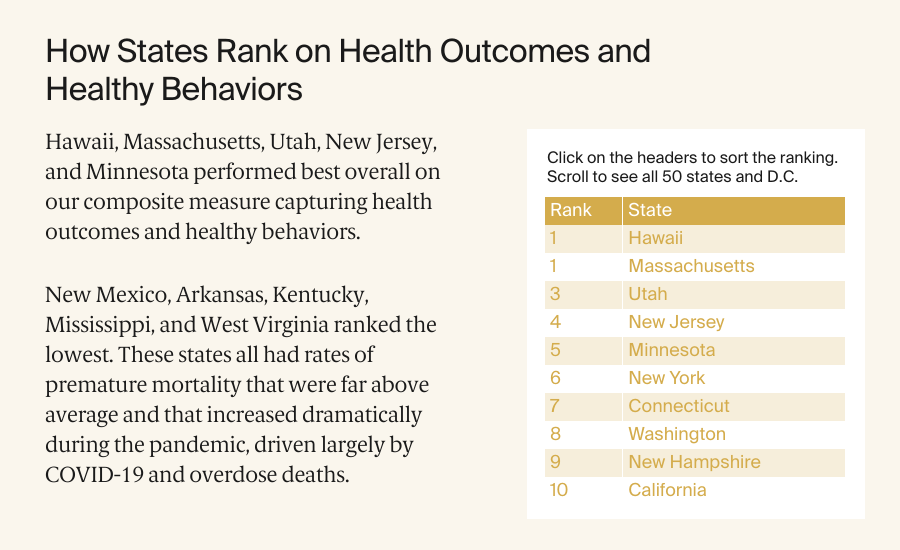

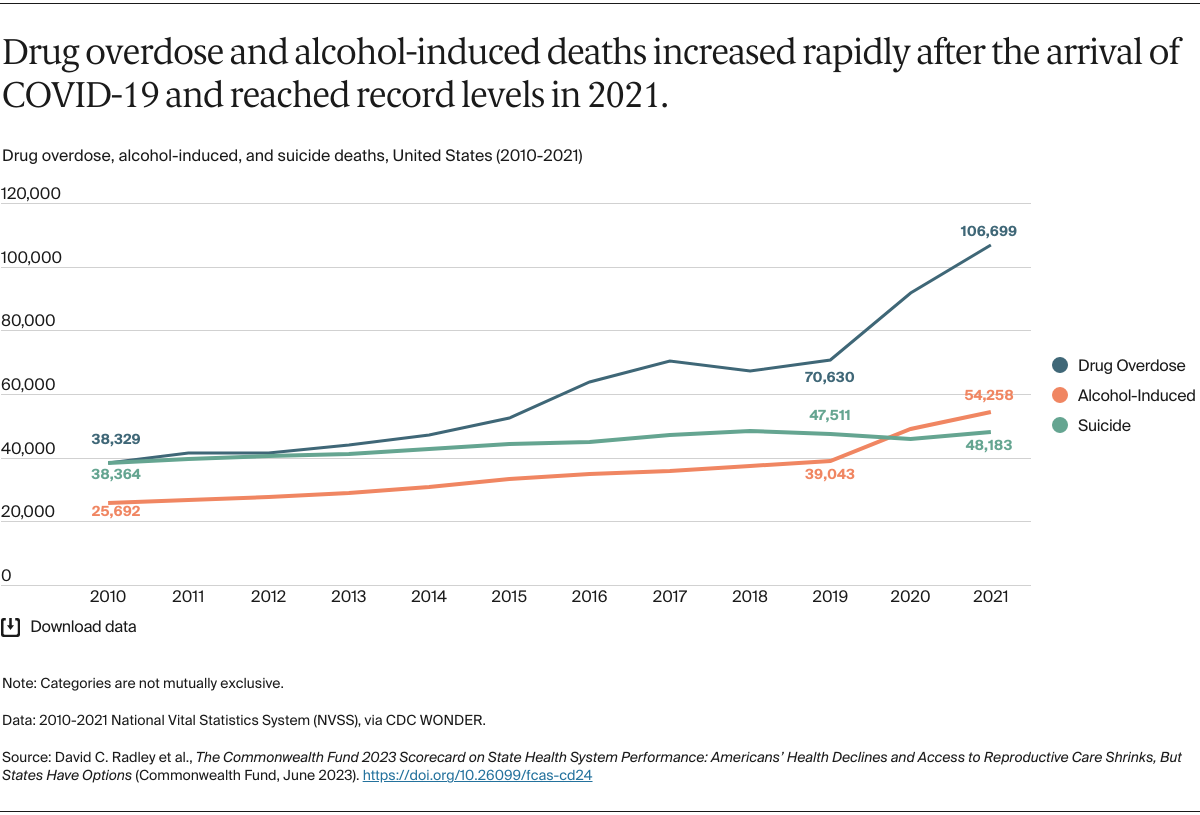

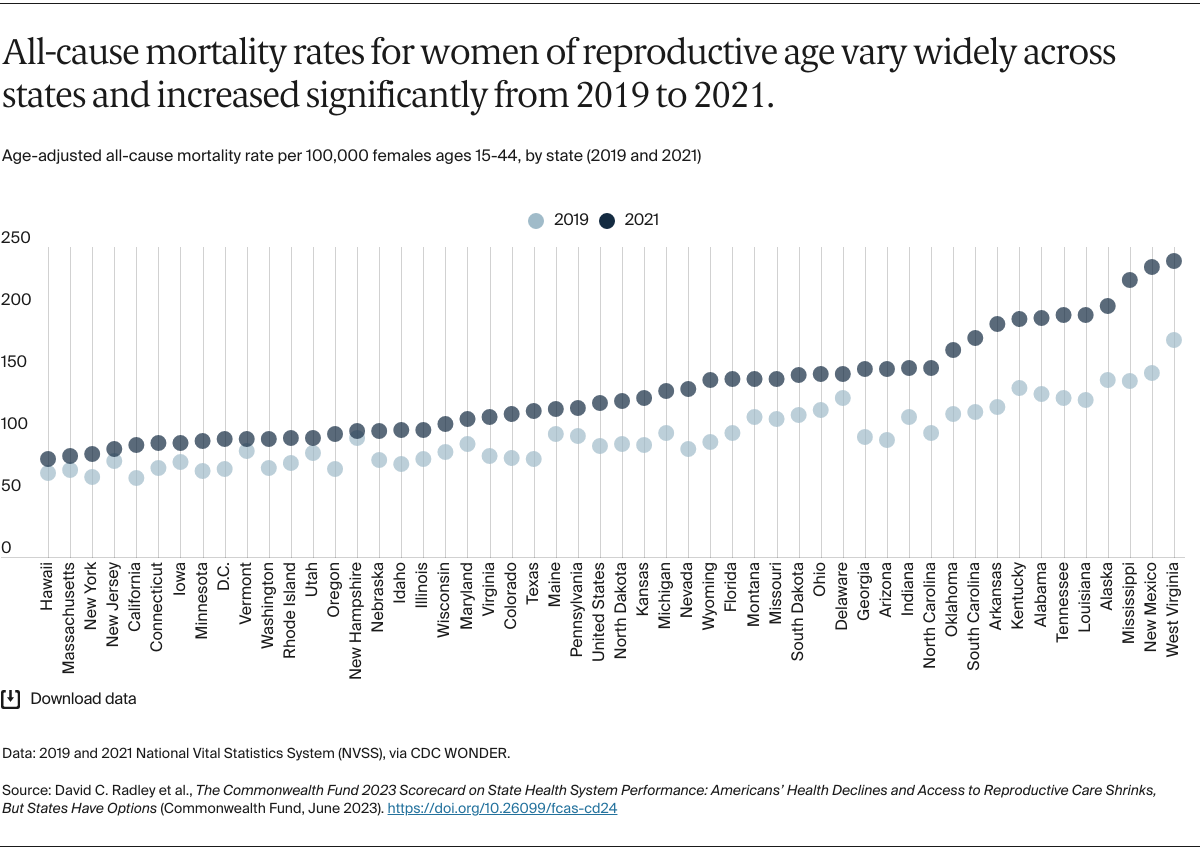

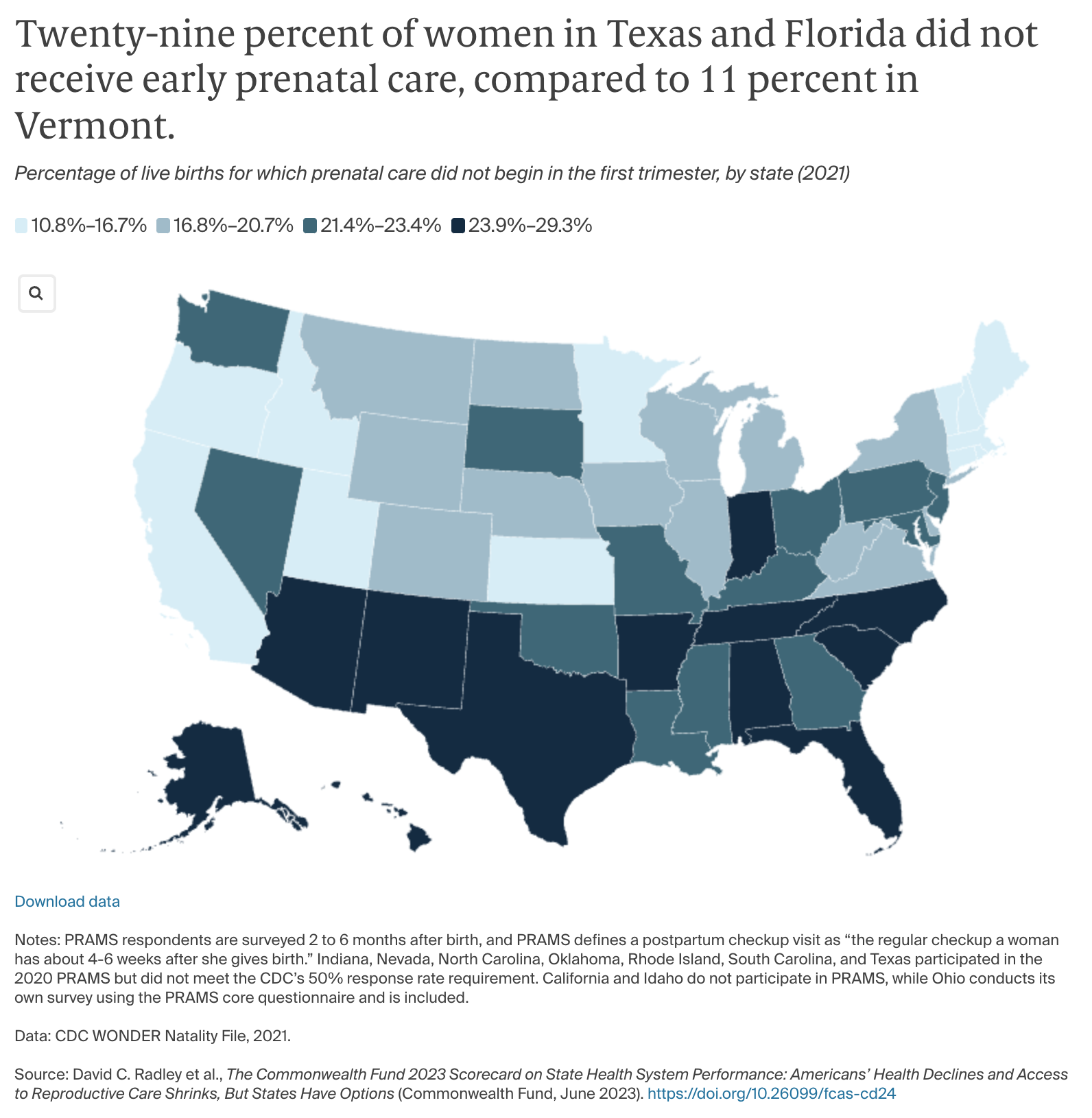

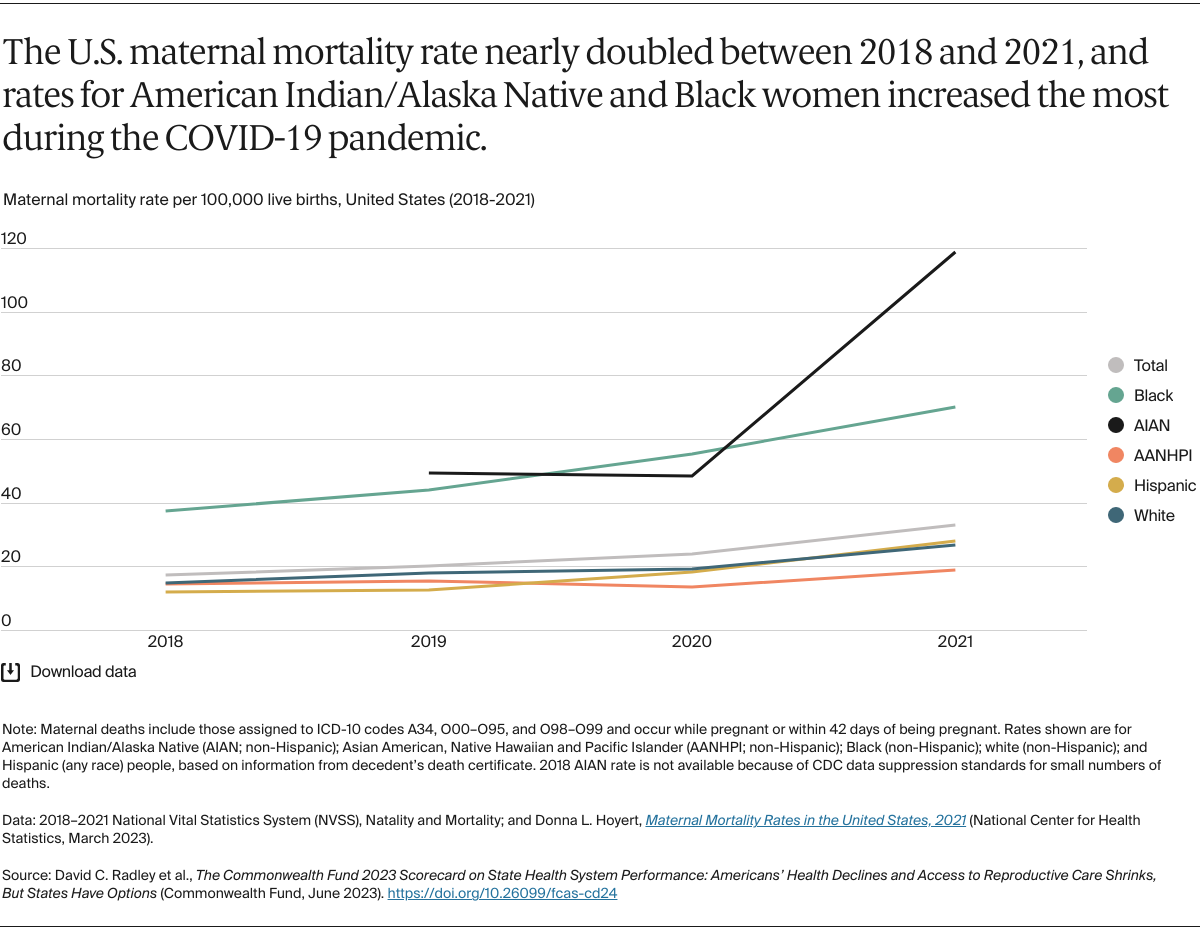

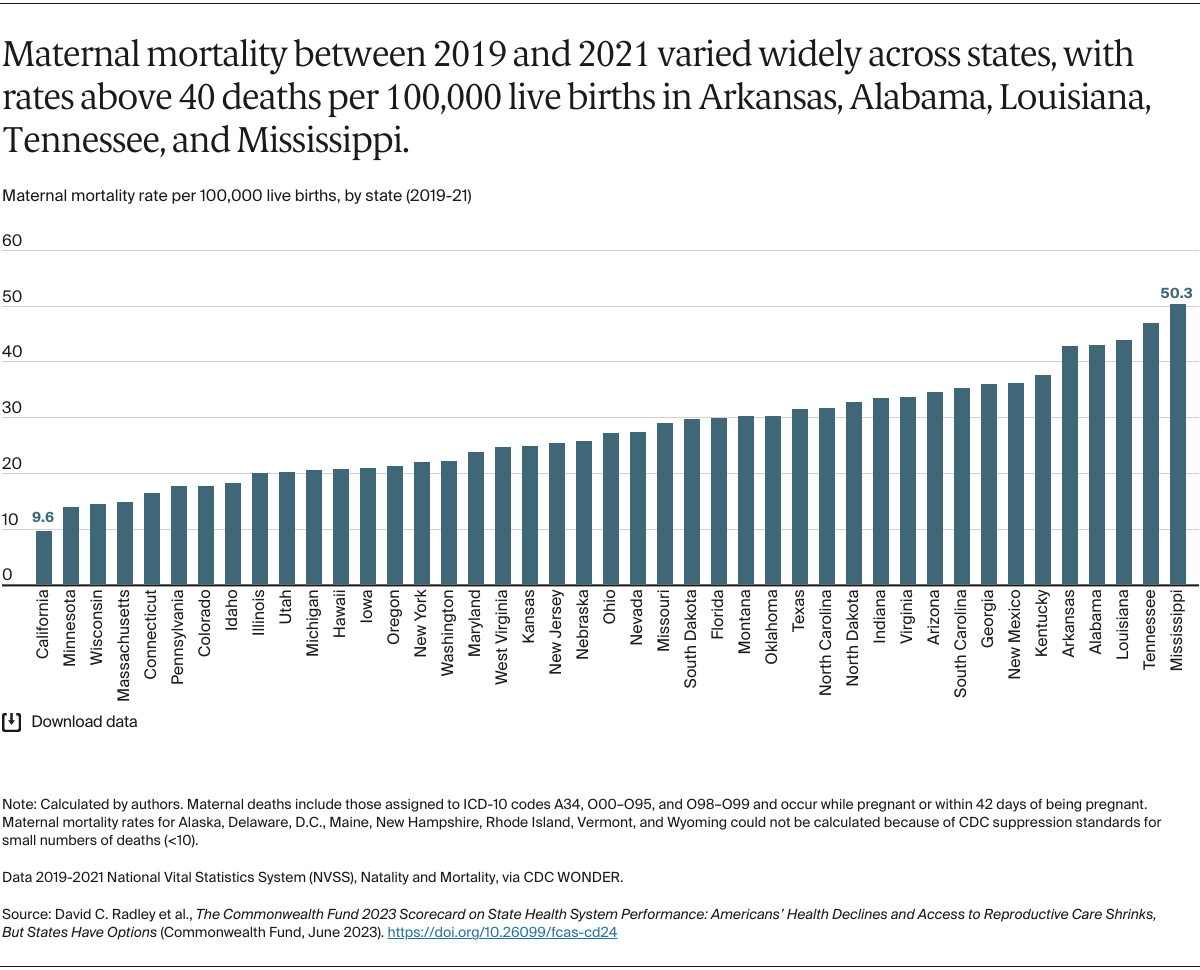

Healthy Lives (10 indicators): includes measures of premature death, health status, health risk behaviors and factors (including smoking and obesity), and tooth loss.

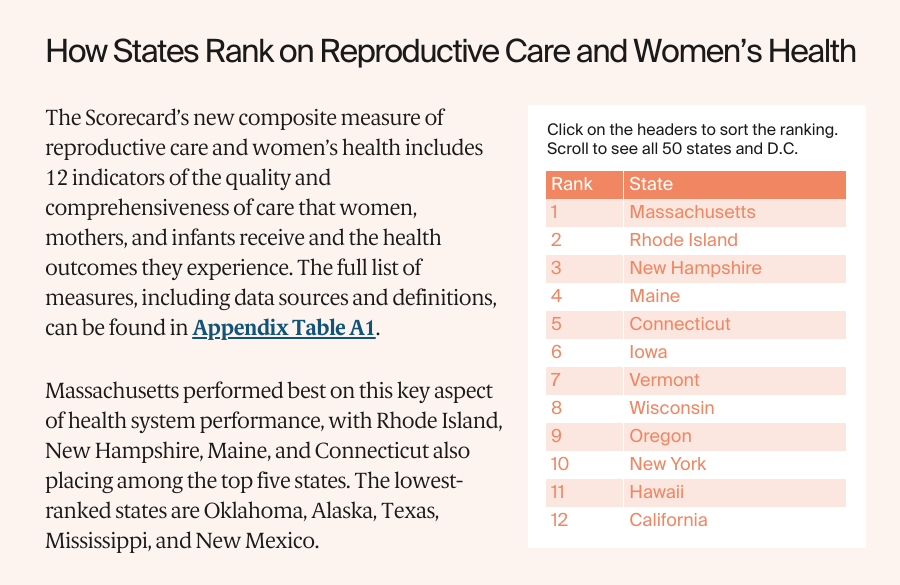

Reproductive Care and Women’s Health (12 indicators): includes measures to reflect health outcomes and access to important health services for women, mothers, and infants, including mortality, such as maternal and infant deaths; high-risk events, such as severe maternal morbidity and preterm births; and access to important health services, like routine checkups and prenatal or postpartum care. Certain measures in this domain have appeared in the Healthy Lives dimension (e.g. infant mortality, cancer deaths, maternal mortality) in previous scorecards. We include performance data for each of the 12 metrics in each state’s 2023 State Scorecard profile, along with data for different racial and ethnic groups on six of the metrics.

The development of this new dimension was made possible through collaboration with Dr. Laurie Zephryin of the Commonwealth Fund, along with helpful feedback from Dr. Eugene Declercq of Boston University and Kay Johnson of Dartmouth Medical School.

INCOME DISPARITY DIMENSION

This year, the State Scorecard reports on performance differences within states associated with individuals’ income level for 19 of the 49 indicators where data are available to support a population analysis by income; these indicators span four of the five dimensions. For most indicators, we measure the difference between rates for a state’s low-income population (generally less than 200% of the federal poverty level) and higher-income population (generally more than 400% of the federal poverty level). For elderly adult indicators built from Medicare claims (e.g., potentially avoidable emergency department visits age 65 and older), we measure the difference between beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicaid and those who are not. States are ranked on the magnitude of the resulting disparities in performance.

The income disparity indicators are different than those used in previous scorecards; hence, these disparity rankings are not strictly comparable to those published previously. For some indicators, we combined multiple years of data to ensure adequate sample sizes for stratified analysis.

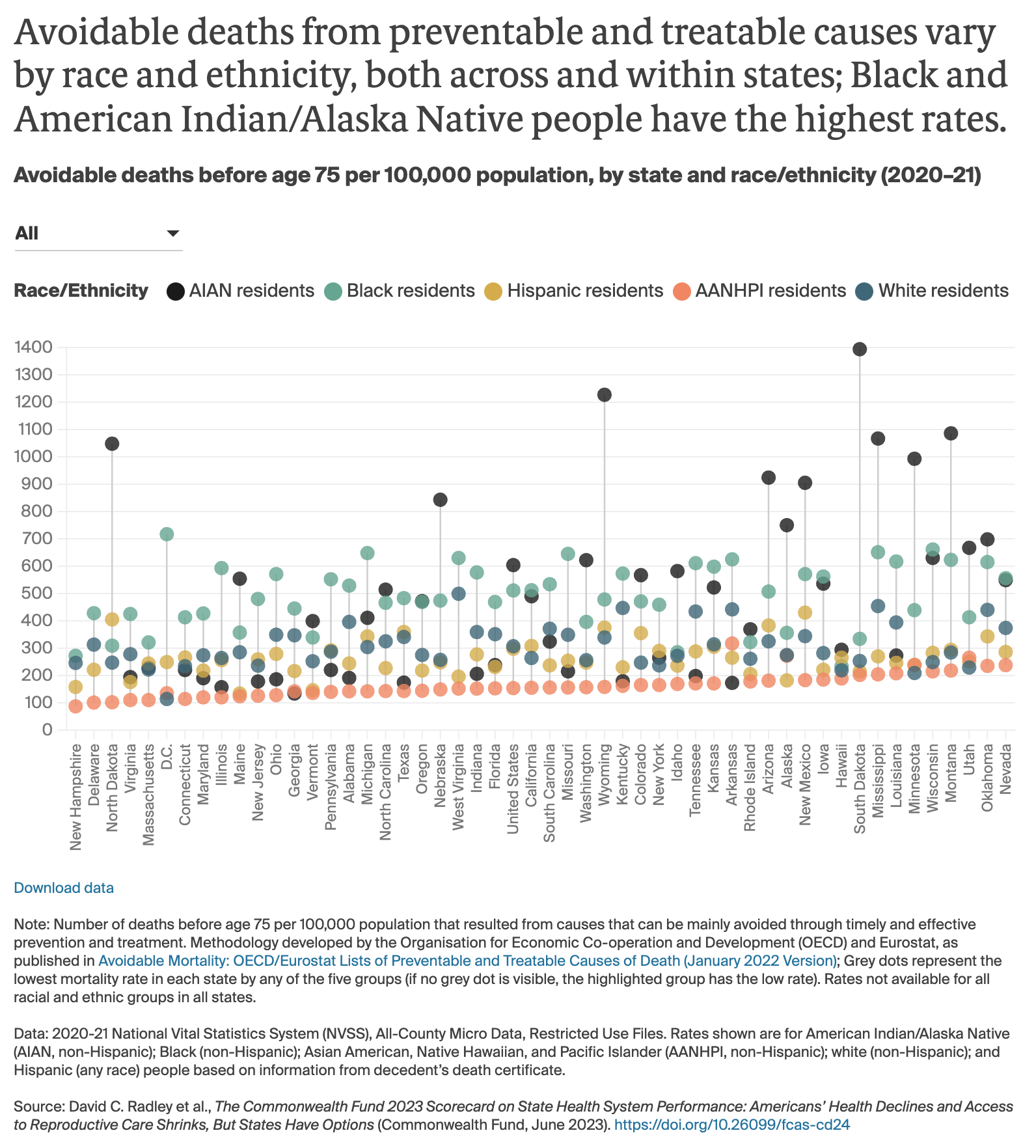

RACIAL AND ETHNIC HEALTH EQUITY DIMENSION

As in 2022, the State Scorecard ranks states based on racial and ethnic health equity. To do this, the report uses updated data metrics and employs the same scoring method used in the Commonwealth Fund November 2021 report, Achieving Racial and Ethnic Equity in U.S. Health Care: A Scorecard of State Performance, to produce summary state health system performance scores for each of four racial and ethnic groups.

That report and method aggregates data on 25 performance indicators (reflecting health outcomes, health care access, and health care quality), stratified by race and ethnicity for Black (non-Hispanic), white (non-Hispanic), Hispanic (any race), American Indian/Alaska Native (AIAN, non-Hispanic), and Asian American, Pacific Islander, and Native Hawaiian (AANHPI, non-Hispanic) populations.

Each population group in each state receives a percentile score from 1 (worst) to 100 (best) reflecting the state’s overall health system performance for that group relative to all other population groups in all states. This enables comparisons within and across states. For example, a state health system score of 50 for Hispanic individuals in California indicates that the health system is performing better for those residents than Hispanic people in Texas, who have a score of 8, but worse than white residents in California, who have a score of 89.

The updated overall percentile scores for AIAN, AANHPI, Black, and Hispanic people are used in this year’s State Scorecard to reflect each state’s performance for non-white racial and ethnic groups. States were evaluated and ranked on their health system performance for each of the four groups separately (contingent on data availability), and those scores were then combined for the state’s final overall composite score. Summary scores for each group can be found in Appendix Table I1. State health system performance scores for white residents are included in the appendix for comparative purposes.

We also include performance data for each of the 25 metrics used in that equity report — updated to the most current year — in each state’s 2023 State Scorecard profile.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

The following principles guided the development of the State Scorecard:

Performance Metrics. The 58 metrics selected for this report span health care system performance, representing important dimensions and measurable aspects of care delivery and population health. Where possible, indicators align with those used in previous scorecards. Several indicators used in previous versions of the State Scorecard have been dropped either because all states improved to the point where no meaningful variations existed (for example, measures that assessed hospitals on processes of care) or the data to construct the measures were no longer available (for example, hospitalizations for children with asthma). New indicators have been added to the State Scorecard series over time in response to evolving priorities or data availability (e.g., measures of COVID-19 vaccination status and medical debt).

Measuring Change over Time. We were able to track performance over time for 50 of the 58 indicators. Not all indicators could be trended because of changes in the underlying data or measure definitions, and some reflect newly collected data (e.g., COVID-19 vaccination).

For indicators where trends were possible, the baseline period generally reflects two to three years prior to the time of observation for the latest year of data available (often 2019), with the intent to use a baseline period prior to the emergence of COVID-19 in 2020. See Appendix Table A1 for baseline and current data years used in the report.

We considered a change in an indicator’s value between the baseline and current-year data points to be meaningful if it was at least one-half (0.5) of a standard deviation larger than the indicator’s combined distribution over the two time points — a common approach used in social science research. We did not formally evaluate change over time for indicators in the income or racial equity dimensions.

Data Sources. Indicators generally draw from publicly available data sources, including government-sponsored surveys, registries, publicly reported quality indicators, vital statistics, mortality data, and administrative databases. The most current data available were used in this report whenever possible. Appendix Table A1 provides detail on the data sources and time frames.

Scoring and Ranking Methodology. For each indicator, a state’s standardized z-score is calculated by subtracting the 51-state average (including the District of Columbia as if it were a state) from the state’s observed rate, and then dividing by the standard deviation of all observed state rates. States’ standardized z-scores are averaged across all available indicators within the performance dimension. States with missing values for a specific indicator are not assigned a z-score for that indicator, but are still assigned a dimension score based on their values for other indicators within the dimension. Dimension scores are averaged into an overall score, and ranks are assigned based on the overall score. This approach gives each dimension equal weight and, within each dimension, it weights all indicators equally. This method accommodates the different scales used across State Scorecard indicators (for example, percentages, dollars, and population-based rates).

As in previous scorecards, if historical data were not available for a particular indicator in the baseline period, the current-year data point was used as a substitute, thus ensuring that ranks in each time period were based on the same number of indicators.

REGIONAL COMPARISONS

The State Scorecard groups states into the eight regions used by the Bureau of Economic Analysis to measure and compare economic activity. The regions are: Great Lakes (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin); Mid-Atlantic (Delaware, District of Columbia, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania); New England (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont); Plains (Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota); Rocky Mountain (Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Utah, Wyoming); Southeast (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia); Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas); and West (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Washington).