To control rising prescription drug costs, the U.S. Congress is currently considering legislation to allow the Medicare program to directly negotiate pharmaceutical prices with drugmakers. A bill in the House of Representatives, H.R. 3, would rely on international benchmarks to set upper limits for prices. But according to recent media reports, the Senate is considering using domestic price benchmarks for Medicare negotiations, which could be based on prices paid by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) or any number of other government purchasers.

Below we delve into what’s known as domestic reference pricing, including the various pricing benchmarks that Medicare might use in negotiations with drug companies.

What is domestic reference pricing, and what role might it play in Medicare drug price negotiations?

Domestic reference pricing is an approach to informing price negotiations with drug manufacturers by calculating a benchmark price, or reference price, based on U.S. prices for a given medication. The reference price also can be based on prices for therapeutically comparable medications — those in the same pharmaceutical class or those with the same mechanism of action. As is the case with international reference pricing, the domestic reference price represents a percentage of whichever pricing benchmark is chosen (see below). If used the same way as international reference pricing in H.R. 3, this percentage establishes an upper limit, or maximum, to bound the negotiation process.

Which benchmarks could be used for domestic reference pricing?

Domestic referencing pricing could be based on one of the current statutory definitions for U.S. drug prices. In order from highest to lowest cost, these include:

- Wholesale acquisition cost (WAC): Price set by the manufacturer that’s often referred to as the list price, before any discounts or rebates. Publicly available.

- Average manufacturer price (AMP): Average price wholesalers pay for a drug distributed to retail pharmacies, either through wholesalers or through sales directly from manufacturers to pharmacies. Does not include drugs distributed through mail-order pharmacies or payer discounts or rebates. The AMP, which is not publicly available, is used to calculate Medicaid rebates — the partial cost refunds that drug manufacturers provide.

- Nonfederal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP): Average price wholesalers pay for drugs distributed to nonfederal purchasers. It reflects some discounts, but no rebates or discounts provided to payers. Not publicly available.

- Federal supply schedule (FSS): Price negotiated between manufacturers and the VA. Available to all federal direct purchasers of pharmaceuticals, among them, the Department of Defense (DoD), Public Health Service, Coast Guard, Bureau of Prisons, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and Department of State. However, FSS prices may not be the prices that federal purchasers actually pay, since some can negotiate further manufacturer discounts, either on their own or in tandem with other federal purchasers. Publicly available.

- Federal ceiling price (FCP): Price used to determine the maximum amount charged to the “Big Four” agencies — VA, DoD, Public Health Service (including Indian Health Service), and Coast Guard. Equal to 76 percent of a drug’s previous-year non-FAMP, minus the difference between the price increases and inflation (as measured by the consumer price index for all urban consumers). The Big Four can negotiate further discounts from manufacturers to determine the final price paid. Not publicly available.

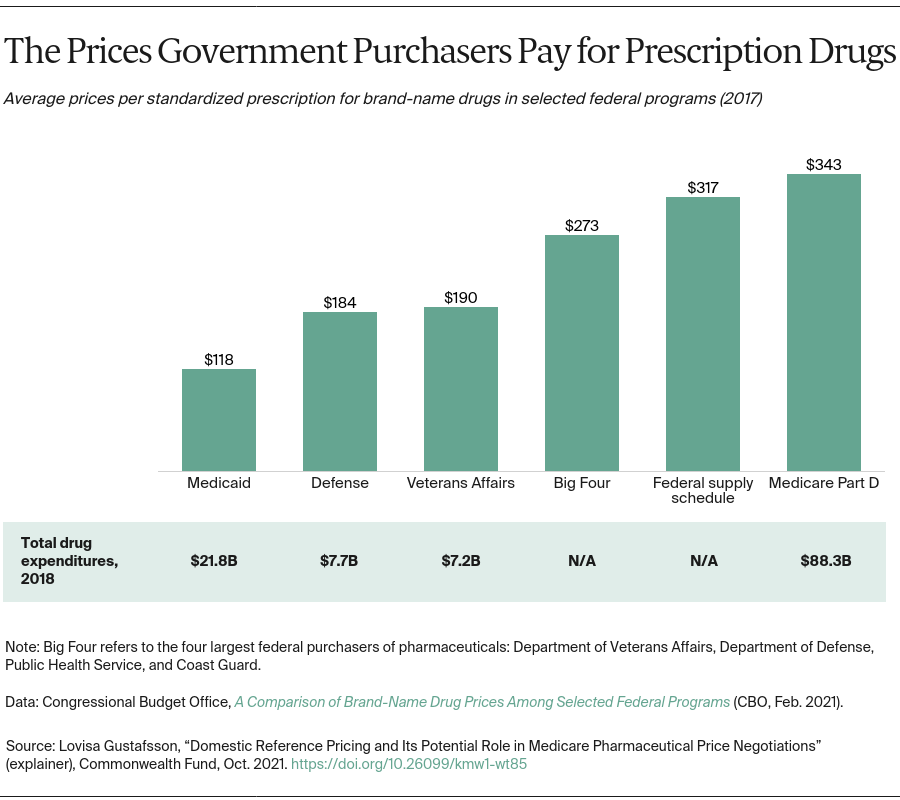

The Congressional Budget Office recently released a report comparing these pricing benchmarks to the prices of best-selling drugs in several federal health programs — Medicare Part D, Medicaid, the VA, and the DoD. Despite being the largest program, Part D — which doesn’t use a pricing benchmark — paid among the highest prices. In comparing net prices for high-priced drugs, Part D pays nearly triple the prices Medicaid pays and nearly double those paid by the DoD and VA.