Interviews conducted by Gordon Moore, MD

Marty Levine, MD, of Shoreline, Washington, doesn’t practice medicine in the same way that most primary care physicians do today. He hasn’t worried about billing anyone for two years. He takes his time with each patient, often lingering over medically irrelevant conversations about patients’ cats or grandkids. When it’s time to fill out a patient’s electronic health record, he pulls up a chair alongside the patient and they do so together. He works closely with a team of health coaches who not only make sure that every patient in his practice understands and follows through on his or her care, but that it’s exactly the right care for that particular patient. On occasion, he makes honest-to-goodness house calls.

“I feel fortunate to work here,” says Dr. Levine, who is employed by Iora Health, a small but growing group of practices that provides medical home–style care to about 40,000 people in 11 states. The medical home model emphasizes patients’ needs, rewards good outcomes, and gives practitioners all kinds of support. “Iora has designed a care model that supports real primary care and lets me focus on being a doctor. None of the doctors here are paper pushers. We get to enjoy taking care of patients.”

Most primary care doctors—in both the United States and the United Kingdom—aren’t so fortunate, however, and work in environments where rushed schedules, paperwork, and discontent are the norm.

In fact, a 2015 Commonwealth Fund survey of primary care doctors found that about one-third of U.S. and U.K. primary care physicians are dissatisfied with practicing medicine. Doctors interviewed for this story confirmed those findings. And primary care physicians also reported that they’re having a hard time managing their sickest patients and/or those with mental illness, using health information technology, and coordinating care outside of office settings, among other activities. These issues are likely to be compounded by a shortage of primary care doctors. In the U.K., nearly 30 percent of primary care doctors plan to retire or change careers within five years. In the U.S., just 24 percent of medical school graduates today say they are headed toward a career in primary care.

That the U.S. primary care system should be fraying is not surprising given that its fee-for-service payment system, which often favors high-cost procedures over primary care services, has led to an underinvestment in the field. The U.K., on the other hand, has long valued primary care. There, the National Health Service (NHS) pays the tab for all primary care and requires patients to register with the local practice of their choice. A network of walk-in centers that don’t require registration or appointments is also available. And the NHS is decidedly primary care–friendly—the director of the agency recently referred to primary care as the “crown jewel” of the system. But primary care doctors, or general practitioners (GPs) in British parlance, are feeling strained by their workload.

It’s critical that both countries adequately support primary care and its providers, as research undertaken from the 1990s to today demonstrates the value of investment in primary care. Studies have consistently found that in regions with higher ratios of primary care physicians to residents, mortality rates from heart disease, cancer, and stroke all tend to decline. Infant mortality and low birthweight rates drop as well. And healthy lifestyle indicators—related to diet, exercise, seat belt use, and smoking cessation—all go up. Another study found an essentially linear relationship between the quality of a country’s primary care system and the health outcomes of patients. The same study found an equally compelling inverse relationship between primary care quality and overall costs.

Today, both the U.S. and the U.K. are in the process of instituting changes that could have profound effects on primary care in the two countries. In the U.S., an array of powerful regulatory and market forces is now aligned to promote primary care. The six-year-old Affordable Care Act contains provisions to better compensate primary care doctors and to promote accountable care organizations and medical homes—care delivery models built on a strong primary care foundation. In fact, many elements of NHS primary care, such as per-patient or capitated payments and long-term doctor/patient relationships, are part of this integrated approach to care. Employers are strong proponents of primary care as well, with many supporting the move to a medical home–based delivery system.

In England, primary care doctors have taken on more responsibility as part of NHS reforms. Over the past five years, the English NHS has been undergoing a decentralization effort in which newly created general practitioner (GP) commissioning groups—overseen by a NHS Commissioning Board—have 80 percent of the NHS budget to directly contract out health care, including hospital and specialist care, for their patients.

At the same time, primary care is becoming more demanding as both nations’ populations age and more people develop multiple chronic illnesses. Today, a larger share of a doctor’s patients is sick and requires care coordination with specialists as well as mental health and community services.

To help understand some of the day-to-day challenges primary care doctors face, The Commonwealth Fund conducted interviews with nearly two dozen doctors in a variety of practice settings in the U.S. and the U.K. Some clear themes emerged: While people love their work with patients, frustration levels are high. Electronic medical records are, for some, a distraction. Work/life balance is often a myth.

What follows is a look at the trends, opportunities, and regulatory changes that could help make a career in primary care a more attractive option.

Primary Care Today

Time Pressure and Stress

Primary care physicians’ jobs are often hectic and taxing. Sixty percent of U.K. primary care doctors say that their job is very or extremely stressful, as do 43 percent of U.S. primary care physicians, according to The Commonwealth Fund’s survey. Likewise, a 2015 online survey by Medscape found that 50 percent of U.S. family practice physicians report some degree of on-the-job “burnout,” defined as either losing enthusiasm for work or feeling a low sense of personal accomplishment. That’s among the highest reported rate of any medical specialty and it’s 5 percent higher than was reported just two years earlier.

A common complaint among primary care doctors that surfaced in the interviews: too many bureaucratic tasks.

The Commonwealth Fund’s survey found 54 percent of U.S. doctors and 21 percent of U.K. doctors say that time spent on administrative issues is a major problem. These burdens take many forms: dealing with dozens of different insurance companies all of which have different processes and rules (U.S. only); recording voluminous amounts of data to satisfy meaningful use or other quality requirements; capturing quality data for various payers; fielding (unpaid) emails from patients; and so on. Such tasks add up, financially and personally. U.S. physicians are spending $15.4 billion per year tracking and reporting quality measures to private insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid, according to a new study in Health Affairs. And many physicians report working extremely long hours just to try to stay above water.

Jane Hartline, MD, whose Tucson, Arizona, practice is just joining an accountable care organization, notes that she manages by limiting her patient caseload and only working four days a week. Even so, she remains frustrated by “doing paperwork to get things approved by the insurance companies and the pharmacy benefit providers.” Dr. Hartline also laments not getting paid for conversations with patients which, she says, are never captured in documentation but which eat up a significant amount of time on a daily basis. Nevertheless, she also says, “I really like my practice. I really like what I do. My current job is the best job I’ve ever had.”

And while no delivery system model offers complete relief from the burden of administrative work, things may be somewhat more manageable in integrated health systems in which doctors are salaried and may have less pressure to code interactions for billing purposes. There, physicians tend to have a substantial administrative support team behind them and a generally smaller patient load as well.

But even there, administrative hassles are part of the daily routine. Heather Wolf, MD, who practices at Kaiser Permanente in Richmond, California, uses a coping strategy that appears to be commonplace throughout the industry. “The reality is that the amount of work to be done is probably for most people impossible to complete in daytime business hours [but] rather than stay in the office until 7:30, I go home and do it there.”

Doctors in the U.K. offer a slight variation on the same theme. There, complaints are not just about paperwork but also the “relentless appointment treadmill.” In fact, general practitioners in the U.K. spend less time with their patients than in any other country: doctors there spend 11 minutes on average talking to each patient. Many physicians fear that such short face-to-face interactions could lead them to miss important symptoms, misdiagnose illnesses, and undermine their patient relationships.

“The overload comes from the volume of paperwork,” says Emily Symington, BM, BSc, DRCOG, DFSRH, MRCGP, a new GP working just south of London. “The volume of documents that need[s] to be reviewed—the referral writing, referral receiving, processing, discharge summaries, and the clinical letters.” In both the U.S. and the U.K., frustration surrounding administrative work is compounded by a sense that all the data collection may not be truly in service to improving care.

“In the past, professionals who worked in the NHS did it for the love of the job above the money,” Symington continues. “We’re undermining that with bureaucracy and oversight. If you undermine that to too great an extent, then we will all start clocking off at the hour that we’re supposed to clock off.”

A primary care doctor practicing in Springfield, Massachusetts noted that, “When you’re rewarded by achieving a certain threshold for A1c or LDL ... has anyone thought about the possibility that overzealous treatment could actually be counterproductive? Is it achieving quality or achieving data that look like quality? In some cases, it creates an adverse relationship between provider and patient because when folks don’t comply, they become a liability to a provider rather than a challenge for us to solve.”

Electronic Medical Records: Part Tool, Part Distraction

The great hope for electronic medical records (EMRs) has always been that they could help improve health care quality while also making it more efficient. And over the past decade, enormous progress has been made in the transition from paper to electronic health records. Today, according to the Fund’s survey, about 83 percent of physicians in the U.S. use some form of EMR; the number is even higher in the U.K. and the National Health Service is in the middle of a strong push to make all primary care paperless by 2020.

In the U.K., efforts to go electronic started 20 years ago and today British primary care doctors are happier with their EMRs than are U.S. doctors. In fact 86 percent of British primary care doctors are satisfied with their electronic medical records, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s international survey.

“Our software is really pretty user-friendly and thank goodness because it collects a lot of the data we need to report so that’s less that we have to do manually,” says Jenny Law, MRCP, a recently retired British GP of 30 years.

In the U.S., however, the survey found just half of primary care doctors were satisfied with their EMRs. While most recognize the virtues of EMRs (for quickly accessing records, streamlining communications with other providers, facilitating prescriptions, etc.), many dislike them, feeling computers are a distraction in clinical settings. In fact, according to a 2015 American Medical Association survey, roughly half of all respondents reported a negative impact in response to questions about how their EMR improved costs, efficiency, or productivity. Fifty-four percent said their EMRs had actually increased costs overall.

“Our EMR is very clunky and I feel like it was built around billing rather than clinical care,” says Jessica Wong, MD, of San Francisco, California. “There are a ton of extra clicks. I think people who were close to retirement at the time [we adopted EMRs] saw that they would have to assume this new burden of learning EMRs and that kind of ushered some of them out.”

Several physicians noted that well-intentioned “meaningful use” documentation requirements for EMRs that until recently were promoted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) may be partly to blame for increased frustration. Acting CMS administrator Andy Slavitt appears to have heard these concerns and recently announced that the meaningful use program is essentially ended and that it will be replaced with “something better.”

Details of the new replacement program remain sparse, but it will aim to encourage more customization among software vendors and focus on rewarding outcomes rather than on indiscriminately rewarding the use of technology. Another goal is to help promote EHRs that are more user-centered and will support, rather than distract, physicians.

But even in their present state, most U.S. physicians still do value EMRs for performing a variety of important tasks such as looking up records and sending in prescriptions. EMRs have even won converts among some skeptics. “When I first started working on the EMR I hated it,” says Kevin Hopkins, MD, of Cleveland, Ohio. “Give me the paper chart! Now there are things about it that are incredibly valuable, even indispensable.”

Treating the Very Sick and the Mentally Ill

Another stressor facing primary care practitioners today is managing care for the chronically ill. According to the Fund survey, one-quarter of U.S. primary care doctors said their practices weren’t prepared to care for those with severe illnesses or overlapping chronic conditions. Similarly, 30 percent of U.K. doctors reported their practice wasn’t equipped to manage these high-need patients.

“So we’re taking care of things in the office now that people used to get admitted to the hospital for,” Dr. Hopkins says. “No longer am I seeing patients that come in for one acute complaint; they have an acute complaint, but they also have now three other now subacute or even chronic issues that have been bothering them so long they’ve put it off because they’re underinsured, or they have a high-deductible insurance plan. So now in a 20-minute visit I’ve got to handle four complaints instead of one, and we’re seeing a lot more people with complications of chronic disease, and particularly uncontrolled chronic disease.”

Primary care physicians also report that coordinating the care of such patients can be difficult. “The biggest hindrance is the lack of communication between primary care doctors and specialists, and between the [hospitals] and the primary care office when a patient gets admitted,” says Bhavin Jani, MD, of Monroe, Georgia.

Another challenge is the gaps between medical providers and community services that help chronically ill patients, particularly those who are mostly homebound. “Some of the separation between organizations that serve patients and community in the U.K. aren’t conducive to integrated care,” says Simon Bradley, MRCGP, a GP in Bristol, England, who adds that visiting nurse services in particular don’t integrate as well as they should with primary care practices.

Caring for the mentally ill is even more difficult in the two countries. In the U.S., an astounding 84 percent of practitioners reported that they were not prepared to treat severely mentally ill patients.

Several U.S. primary care doctors interviewed said that getting an appointment with a psychiatrist in particular requires a long wait, and that they often end up treating patients with mental health needs themselves. “Finding adequate mental health services for patients who need them can be very, very difficult,” says Dr. Hartline of Tucson, Arizona. “The providers are just too busy.”

U.K. physicians report that recent budget cuts have hit services for the mentally ill especially hard. “The local authority budgets have been cut enormously and mental health has historically been a Cinderella service, which is a real tragedy,” said Simon Poole, MBBS, DRCOG, of Cambridge, England. “Services around mental health have deteriorated. Our waiting lists are increasing rapidly.”

The Future of Primary Care

In both the United States and the United Kingdom, hope that the future of primary care will look brighter rests partly on the promise of long-term, evolutionary changes to payment and delivery systems that are already under way. In the U.S., the Affordable Care Act (ACA) envisions a future dominated by the spread of both accountable care organizations and patient-centered medical homes, two models of delivering care that emphasize primary care. But there are still questions about how well either model truly works and whether practitioners are any happier within such systems.

An accountable care organization (ACO) is an entity formed by health care providers that takes responsibility for the quality and total costs of care for a population of patients. This marks a dramatic shift from the prevailing fee-for-service system and presumably gives providers an incentive to avoid unnecessary care while at the same time insisting on appropriate care. Since 2012, Medicare has rewarded ACOs that meet certain performance benchmarks by allowing them to share in any savings they generate. Today about 400 ACOs serve more than 7 million Medicare beneficiaries. But results from the program’s first few years have been mixed. Only about half were able to meet quality-of-care benchmarks and keep spending below budget targets. So it remains to be seen whether more experience will lead to more significant savings, or whether the model continues to produce only middling results.

One thing is clear, however: providers are not universally enamored. According to a 2015 Commonwealth Fund survey, fully 24 percent of doctors practicing in ACOs felt that they had a net negative impact, another 45 percent either didn’t know or felt they had no impact. Just 30 percent saw some positive impact on quality of care.

The ACA also includes numerous provisions to promote patient-centered medical homes. Medical homes have earned substantial attention over the past few years for their emphasis on comprehensive care coordination, care teams, patient engagement, and population health management—all things that appeal intuitively to patients and physicians alike. Medical homes have sprung up in every state in the U.S. and today many tens of millions of Americans receive care through a medical home. CMS is concurrently running at least three large-scale medical home demonstration projects. About 30 percent of physicians nationwide say that their practice has been certified as a medical home, although most have only been organized as such for a few years.

Medical homes have a mixed record in terms of quality and savings, but it is important to remember that these are early results. Of the three Medicare demonstration projects, just one can thus far demonstrate an overall positive return on investment, but all three have logged at least some quality gains in terms of reduced emergency department visits, decreased hospital admissions, or other metrics. Nearly half of physicians are positive in their assessments about the impact of medical homes: 43 percent of doctors practicing in a medical home felt that it had a positive impact on quality while only 17 percent felt that the home had a negative impact.

Another development in the U.S. health care system that bears mention involves the slowly expanding role of nurse practitioners. About 60,000 nurse practitioners (who hold master’s degrees in nursing) work in primary care in the U.S., and both the ACA and the Institute of Medicine (IOM) support expanding their clinical responsibilities to include more diagnosing, treating, and prescribing. The majority of these nurses do not have full practice privileges, making them an untapped resource that could conceivably address the physician shortage in many areas. In reports on the subject, the IOM has noted that nurse practitioners can typically handle between 80 percent and 90 percent of the work performed by a physician with no discernable difference in terms of quality of care.

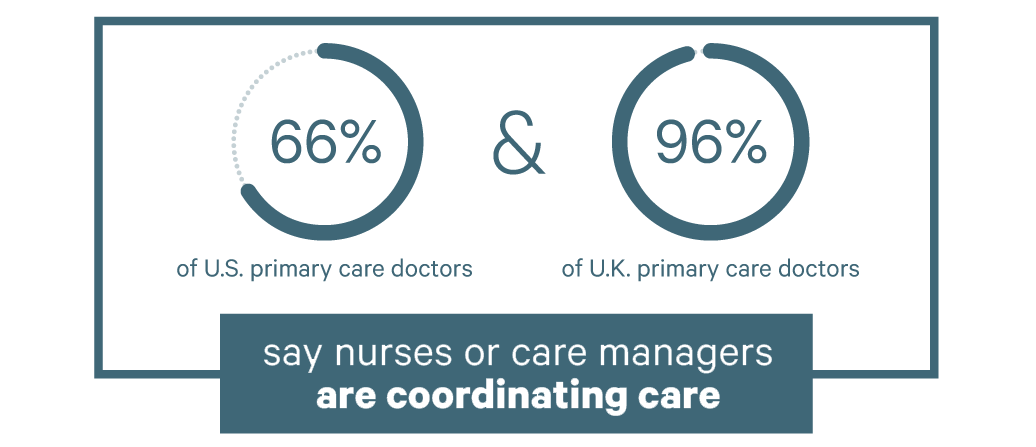

Today, nurse practitioners in 20 states have full practice authority. Nineteen other states require nurses to coordinate with a physician in order to provide care. In fact, 66 percent of U.S. doctors said that nurses or care managers were managing the care of chronically ill patients, according to the Fund survey.

Dr. Hopkins of Cleveland says that working with nurse practitioners enables him to focus on high-level medical decision-making. “One of the most rewarding things for me is working with nurse practitioners, where they have a complicated patient, they come to me, we talk about the patient, I go back in with them to see the patient, we come up with a plan, and I leave and I can go onto the next patient.”

Care teams are playing an even bigger role in the U.K., where 96 percent of doctors said a nurse or care manager was coordinating care. There are also coordination of care efforts under way in NHS England to help primary care practices, hospitals, and community services work together more efficiently—as well as new funding to bolster community and mental health services.

Last year NHS England announced plans to recruit 5,000 new primary care doctors by 2020 and to increase the budget for primary care by 4 percent to 5 percent each year until 2021. There’s also a comprehensive 10-point plan to improve recruitment and retention of primary care doctors (that emphasizes reducing bureaucracy and workload, improving public perception of GPs, and hiring more physician assistants and pharmacists to work alongside primary care doctors).

And a new five-year plan published in April 2016 calls for €26 billion for primary care services. Along with paying for GP recruitment, the package will fund support for primary care doctors suffering stress and burnout and streamlined inspections for the best-performing practices.

“I think we’ll look back on the NHS’s proposal as a real turning point for primary care in England,” says Martin Roland, DM, BM BCh, professor of health services research at the University of Cambridge and special advisor to RAND Europe. “It includes meaningful provisions for addressing workload, and a major commitment of funds over the next four years.”

Whether any of these changes will successfully address physicians’ concerns and attract more professionals to primary care remains to be seen, but at least some observers are cautiously optimistic.

“Many health care reform efforts today are designed to promote primary care, streamline administrative burden, and pay primary care providers for value,” says Melinda Abrams, vice president of delivery system reform at The Commonwealth Fund. “Primary care may be a field in the middle of an overhaul but the status quo is unsustainable, and there are important signals that indicate that it will come out on the other side as a fundamentally much more attractive profession.”

Recognizing the Value of Primary Care

Primary care is in a state of flux. Delivery systems are changing. Payment systems are changing. Patients and providers are learning to incorporate technology into health care and into the doctor-patient relationship. All of this makes now an especially unsettling time for primary care doctors.

But the future does hold enormous promise. There is broad recognition of the inherent value of primary care and changes promoted both here and in the U.K. are specifically designed to increase provider autonomy and compensation; reduce administrative burden and workload; and swell the ranks of the primary care workforce. These efforts are not new, but neither are they mature—what many of them may need most is simply the time to take root and grow, with appropriate fine-tuning along the way. With time, these efforts may lead a new generation of physicians to understand what many know already: primary care is among the most rewarding careers available in medicine.

“I really like what I do,” says Brian Sullivan, MD, a primary care doctor who practices in Dubuque, Iowa. “I like taking care of patients. I like having relationships that build. It’s very rewarding. I really wouldn’t want to do anything else.”