Key Findings

Plans rely on independent agents to support membership growth. Ninety-six percent of Medicare Advantage and Part D plans contract with independent agents.3

Independent insurance agents are authorized to enroll individuals in Medicare plans and contract with one or, typically, more insurance carriers. Though it is not required, many agents affiliate with broker agencies that provide services such as marketing, technology, training and compliance, and administrative support. Licensed agents (and affiliated agencies) are compensated by the carriers directly on a per-enrollee basis. The more enrollments and renewals that agents generate, the higher their earnings. This means that carriers’ and agents’ incentives for growth are perfectly aligned.

Becoming a licensed, active Medicare agent is typically a three-step process4:

- Secure a state-issued health insurance license.

- Complete a certification (for example, through America’s Health Insurance Plans).

- Undergo product and sales training from contracted carriers.

To govern the marketing and communications of Medicare Advantage, Part D prescription drug plans, and the 1876 Cost Plans, CMS establishes the “Medicare Marketing Guidelines”5 and revises them annually. These guidelines lay out how plans and their agents may communicate, educate, and market Medicare plans to beneficiaries, and are the basis for CMS’ oversight of plans’ activities in this realm. These guidelines also govern the actions of licensed agents. Importantly, oversight of the agents is delegated to the carriers themselves. This means that plans are ultimately responsible for agent and agency adherence to the marketing guidelines. At risk of penalties from CMS and erosion of beneficiary confidence, and other licensure-related sanctions from the states themselves, carriers and agents take this obligation seriously. As one health plan executive said, “agents, agencies, and carriers share a market-based interest in ensuring a high degree of compliance.”

Because of the complexity of the plan selection process, many beneficiaries rely on independent insurance agents to help them identify the coverage and benefits options that may best meet their needs.

According to industry experts, agents are also important because many are multilingual and are usually embedded in the communities they serve. Given their local roots, agents can help plans reach a broader spectrum of beneficiaries, including racial and ethnic minorities and nonnative English speakers. Yet beneficiaries have limited ability to gauge the caliber of their agent, as there is no systematic or transparent way either for them or plans to avoid a bad actor. Often, friends or family can provide a referral to an agent, but in other cases it is up to the beneficiary to screen agents.

The agent–plan model can limit plan choice in ways that are not obvious to beneficiaries.

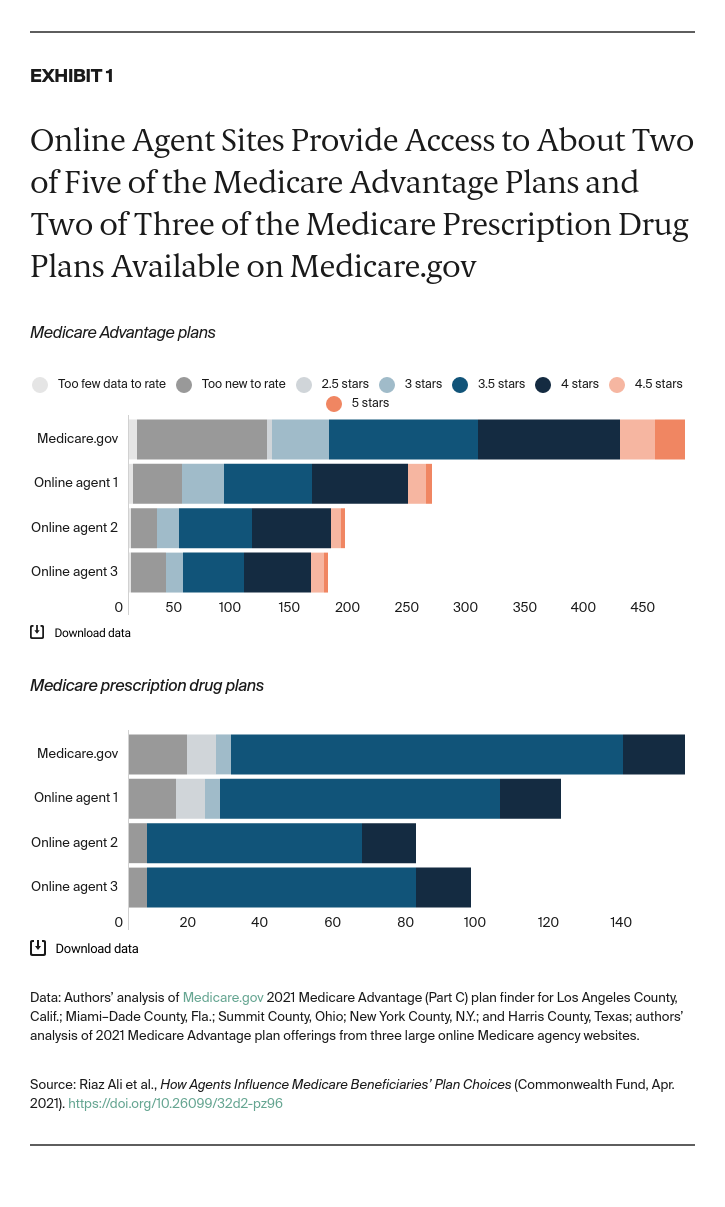

An analysis across five markets of three national, online agent plan selection tools found that, on average, each online agent studied includes less than half (43%) of Medicare Advantage plans and less than two-thirds (65%) of Part D prescription drug plans in that area. (Exhibit 1).

Agents typically secure contracts with multiple carriers, but they are not required to contract with all available carriers in their market. This means that a single agent will not necessarily represent every available plan. In this way, the agent market is filtering plan options, something that may not be apparent to the beneficiary even if the agents and agencies disclose it in their communications.

It is not clear what proportion of total available plans in a given geographical area a typical agent will represent, though it surely varies. As an initial proxy, we conducted a simulated search of Medicare plan options using Medicare.gov and three national, online agent search tools in five markets: Los Angeles County, Calif.; Miami–Dade County, Fla.; New York County, N.Y.; Summit County, Ohio; and Harris County, Texas.

Results varied widely between tools and plan types, but all of the agent tools excluded some of the plans available in the area. Furthermore, only one of these sites offered Medigap plans, and it included less than one-fifth (18%) of the Medigap options available across the five counties.

To understand the quality of the plans offered through online search tools, we also looked at the representation of Medicare Advantage and Part D plans at these online agent sites by star ratings. Overall, the online agent tools we surveyed offer only a limited number of top-rated plans. For instance, in Miami–Dade County, Fla., the online agents offered only three or four of the 10 Medicare Advantage plans with five stars. None of the agents that we surveyed in Summit County, Ohio, or Harris County, Texas, offered the five-star Medicare Advantage plans available in those areas. This may be happening for a variety of factors unrelated to the quality of the plans, such as the incentive structure, the carrier’s investment in or commitment to partnering with agents, or the size of and reach of the carrier (for example, national vs. regional or local).

Regardless of the reason, the fact that agents do not contract with every carrier does not necessarily mean that people will not find a plan that works well for them, nor does it mean that agents will not provide objective guidance. As one former brokerage manager told us: “We would instruct our staff in no uncertain terms that if they were using the tools and found a carrier that’s better for the client that we didn’t carry, just give them the toll-free number and tell them to call there.”

However, there is no explicit imperative or financial incentive for agents to behave this way. Agents are not required to disclose that they do not offer all available plans and beneficiaries may not recognize that agents may not present all options available to them.

Agents’ and insurers’ Medicare resources are widely available online and likely to be among the first information sources seen in online searches.

Digital advertising, communication, and outreach by health plans and agents are common sources of Medicare information, and today these efforts compete with nonprofit and government sources for beneficiary attention. Research shows that a growing number of Medicare beneficiaries rely on online tools for at least part of their research and decision-making.

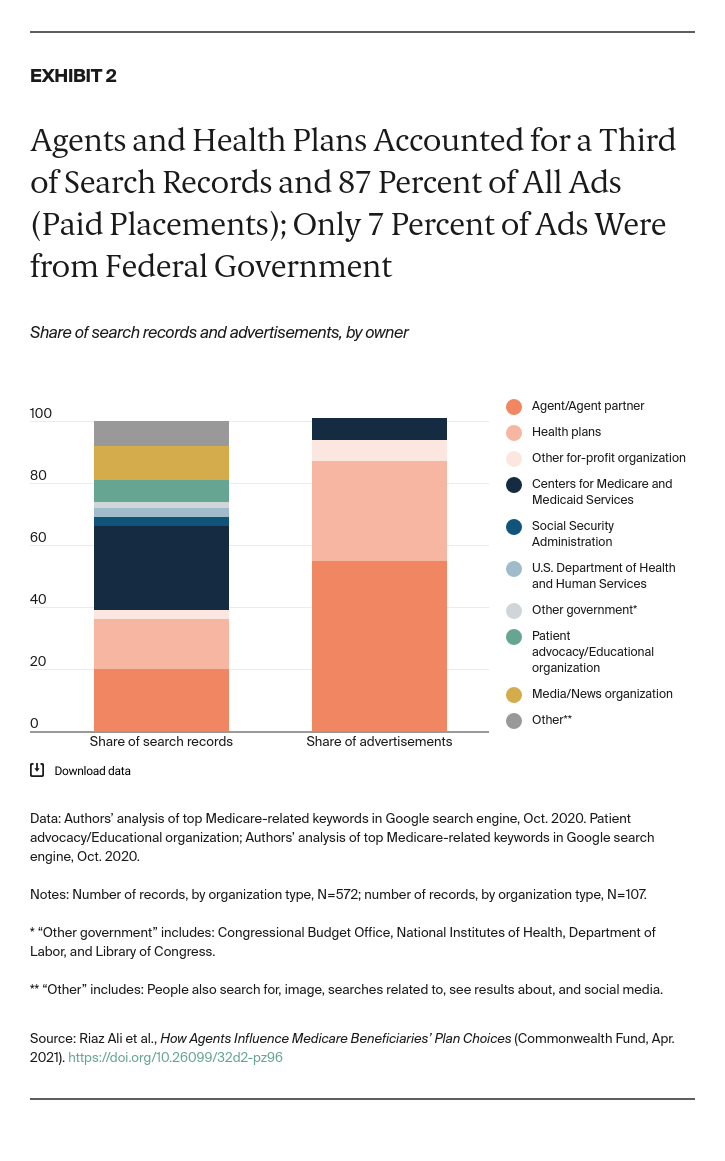

To understand what a typical Medicare beneficiary might encounter when turning to internet-based resources, we simulated a series of online searches. A review of the top-30 Google keywords related to Medicare produced 572 results (Exhibit 2). Following are results from the analysis:

- The federal government accounted for 35 percent of total results, with the majority (78%) linking to CMS-sponsored pages and resources.

- Agents and health plans together represented 36 percent of search records (20% for agents and 16% for health plans).

- Agents and health plans made up 87 percent of search page ads, while CMS accounted for 7 percent.

These results indicate that much of the online information available to beneficiaries is owned by organizations with commercial interests. This raises important questions about the extent to which consumers are aware of the sources, potential limitations in the information, and any potential conflicts or biases that may be inherent in the source. Even though this information is regulated, it may narrow plan choices available to beneficiaries without their knowledge — for instance, if a beneficiary develops a relationship with a brokerage that only works with a select number of Medicare carriers in the beneficiary’s state.