Abstract

- Issue: The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) provides enhanced federal Medicaid funding to states meeting certain conditions, including continuous beneficiary enrollment throughout the public health emergency period regardless of changes that might otherwise affect eligibility. Even when continuous enrollment ends, millions of current beneficiaries will remain eligible for Medicaid, elevating the importance of a wind-down process that adheres to important safeguards against erroneous termination of benefits. New federal guidance gives states broad options for returning to normal operations but a constrained timeframe for doing so.

- Goals: Assess significance, impact, and ultimate implications of winding down the FFCRA continuous enrollment protection.

- Methods: Analysis of legislation, regulations and guidance, and federal and state Medicaid enrollment data.

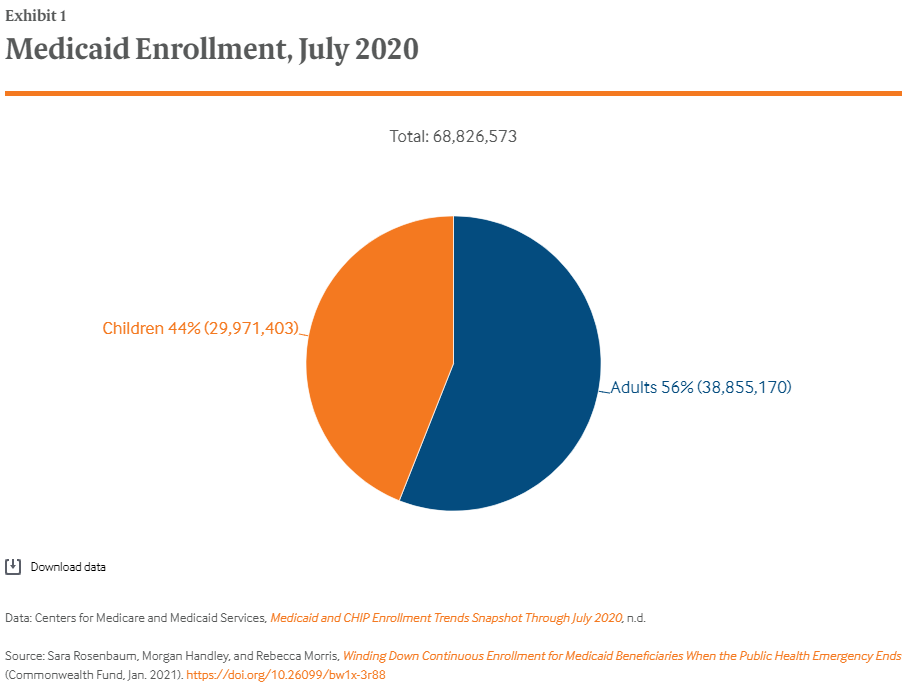

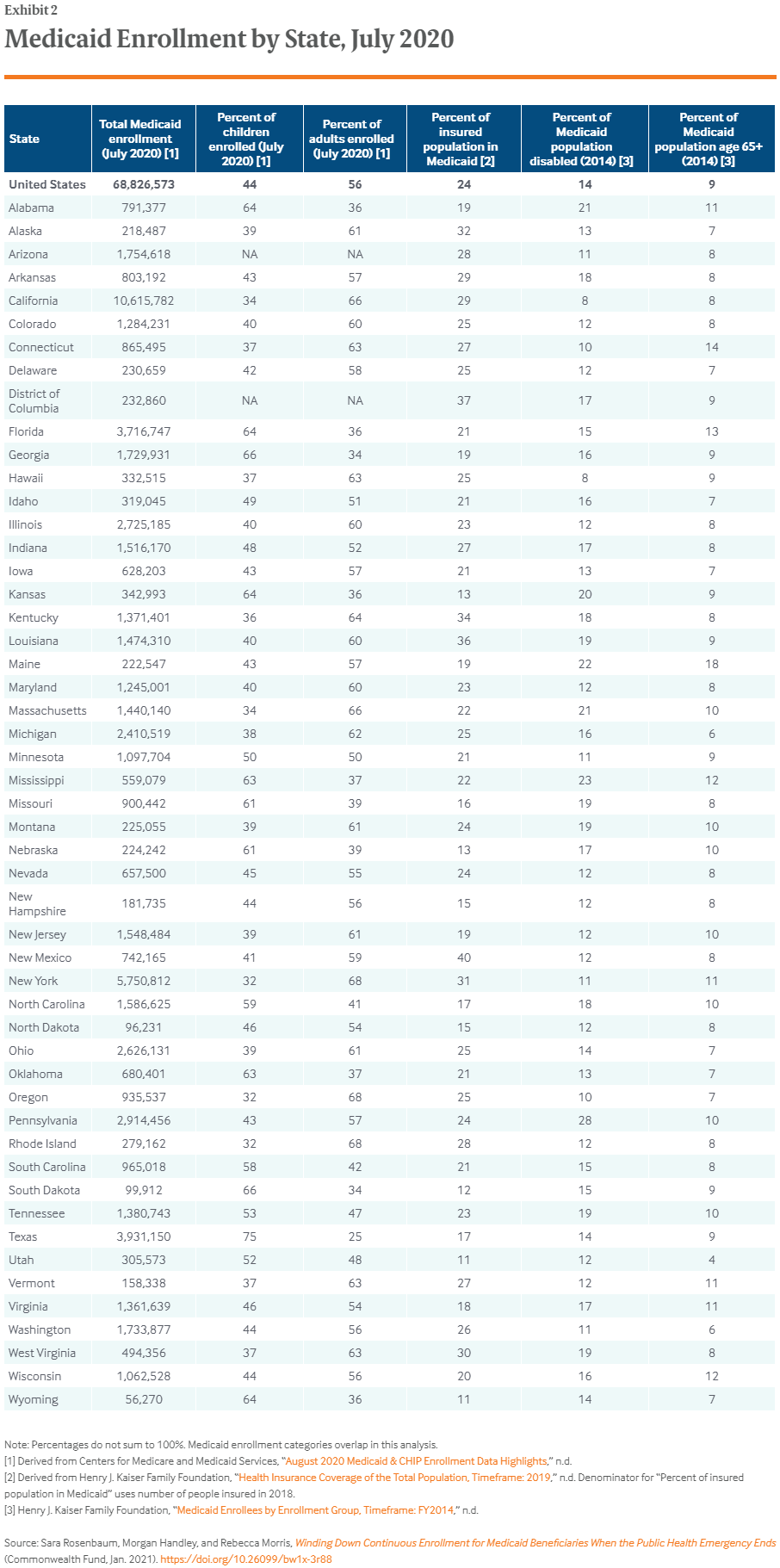

- Key Findings: Erroneous disenrollment could affect tens of millions of Medicaid enrollees protected by FFCRA continuous enrollment, while new guidance on resumption of the normal application and enrollment process could affect millions more. Among more than 68 million beneficiaries enrolled as of July 2020, 44 percent were children, 56 percent were adults, 14 percent were beneficiaries with disabilities, and 9 percent were age 65 and older. State enrollment composition varied significantly, but all states have large numbers of high-need enrollees who depend on continuous care.

- Conclusions: The end of the public health emergency will restore the normal Medicaid enrollment and eligibility redetermination process. Averting erroneous enrollment terminations and lengthy application delays requires detailed guidance, with enhanced federal funding throughout the wind-down period.

Background

To help states address surging health care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic,1 the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) temporarily increases federal Medicaid payments.2 This funding enhancement (6.2 percentage points over the normal state rate) stops at the end of the calendar quarter in which the public health emergency declaration ends. The Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) last extended the declaration on October 23, 2020, meaning that the current period will end on January 23, 2021.3 Were this to happen, the funding enhancement would end the last day of March 2021.

All states are receiving the FFCRA Medicaid enhancement and must satisfy certain conditions that accompany it.4 These conditions bar restrictions on “eligibility standards, methodologies and procedures” beyond January 1, 2020, levels; premium increases beyond January 1, 2020, levels; and cost-sharing for Medicaid COVID-19 testing and treatment benefits, including vaccines.5 The FFCRA conditions also mandate continuous enrollment throughout the federal pandemic public health emergency period for people enrolled in Medicaid on or after the date of enactment (March 18, 2020). This final condition effectively suspends Medicaid’s regular eligibility renewal and redetermination process, which ordinarily happens routinely throughout the year or whenever a state receives information that could affect eligibility. FFCRA allows states to end continuous enrollment only in the case of beneficiaries who voluntarily disenroll or move out of state. However, Trump administration regulations that took effect in November apply this protection only to beneficiaries considered “validly enrolled” in Medicaid, not those enrolled ostensibly as a result of agency error or conviction for fraud.6

On December 22, 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) published guidance for resuming normal eligibility and enrollment operations once the emergency ends.7 Noting the challenges involved in returning to normal, the guidance encourages states to develop a post-COVID eligibility and enrollment operational plan, clarifies that normal safeguards against erroneous denials or coverage continue to apply, and provides states with a broad menu of strategies. This menu includes, among other actions, prioritizing the review process, slowing down application and enrollment timeframes, adopting eligibility and enrollment simplification options, and using older information when processing redeterminations and renewals.

While the guidance provides flexibility and options, it also provides a short timeframe for states to restore normal enrollment and renewal activities. CMS is clear that it expects states to prioritize removing people “likely to be no longer eligible” and who “no longer meet eligibility criteria.” Additionally, FFCRA provides no funding enhancement during the disaster recovery phase.

Significance of the Continuous Enrollment Protection

FFCRA continuous enrollment guards against coverage interruptions that affect access to care. Coverage interruptions are common in Medicaid, even among people who remain eligible for assistance. Indeed, when the continuous enrollment period does end, millions of beneficiaries likely will remain eligible, either under the eligibility group to which they belong or another category because their circumstances may have changed only modestly.8

Medicaid has more than two dozen eligibility categories, each governed by strict rules. Even small changes in life circumstances can end eligibility entirely or cause the category to change.

For example, a small pay increase can cause working parents to lose Medicaid for themselves, while shifting their children from Medicaid to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which uses more generous eligibility rules.9 Similarly, at the end of a 60-day postpartum period, women may shift into the ACA low-income adult expansion group or qualify for more limited coverage under a state’s family-planning eligibility option. A 64-year-old with low income who is receiving full Medicaid coverage through the ACA expansion may, when qualifying for Medicare at age 65, lose full Medicaid, remaining eligible only for Medicaid help with Medicare premiums and cost-sharing. Among beneficiaries whose basis of eligibility is tied to disability or age, changes in health status or financial circumstances can necessitate an eligibility redetermination.

The FFCRA continuous enrollment protection is designed to avert coverage interruption. While modified by the recent rule (which also allows states to move protected enrollees from a more generous to a more narrow coverage category in certain situations, like when they turn 65), the FFCRA protection remains a critical check on disenrollment in the middle of a pandemic.

Medicaid’s Long-Standing Protections Against Erroneous Disenrollment and Benefit Denials

The FFCRA reforms effectively sit atop long-standing provisions of federal Medicaid law, among the most important of which is bedrock protections aimed at avoiding erroneous reduction or loss of benefits.10 Long-standing protections also require states to carefully review applications for new coverage, critical during a period of heightened health care need. These rules are a permanent feature of Medicaid and remain in place during the pandemic. The protections against the wrongful termination of coverage have their basis in federal constitutional due process principles, articulated by the United States Supreme Court in its 1970 landmark case Goldberg v. Kelly, which concluded that the “brutal need” of the poorest Americans outweighs a state’s desire to ensure that people no longer eligible do not receive benefits.11

To guard against erroneous Medicaid termination, states must first conduct a careful review. If changes have occurred that implicate ongoing eligibility under one coverage category, other coverage categories also must be assessed. The results of the review must be communicated through advance written notice and, if a beneficiary asks for one, an impartial hearing prior to a reduction or termination of benefits. FFCRA effectively suspends coverage reductions or terminations during the emergency, but nothing in FFCRA alters the Goldberg protections once the redetermination process resumes.

How Many People Depend on Safeguards Against Erroneous Disenrollment?

Using the most recent Medicaid monthly enrollment information, we sought to gauge the magnitude of the FFCRA continuous enrollment protection in terms of the size of the protected population both nationally and by state. In the case of FFCRA, the protected population equates to the entire enrolled Medicaid beneficiary population, since all beneficiaries depend on the proper functioning of erroneous disenrollment safeguards.

Monthly Medicaid enrollment data available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are reported nationwide and are further sorted into numbers of enrollees who are children or adults. Drawing from Kaiser Family Foundation estimates based on 2014 Medicaid enrollment data, we estimated the percentage of enrollees who are children and adults with disabilities or adults age 65 and older (these percentages are not reported in the monthly data) — and thus especially dependent on FFCRA continuous enrollment and Goldberg safeguards.12

Protected Medicaid Enrollment Population: National, July 2020

CMS reports preliminary data that show that in July 2020, 68,826,573 children and adults were enrolled in Medicaid and thus protected by the FFCRA continuous enrollment policy. (Children whose CHIP coverage is through a Medicaid expansion — approximately 7 million — are excluded from this figure.) The July 2020 enrolled population represents a 4.3 million increase over July 2019 enrollment levels, reflecting a pandemic-related enrollment surge.13 Within the July 2020 population, CMS reports that nearly 30 million (44%) were children and nearly 39 million (56%) were adults (Exhibit 1). We estimate that, within the national enrollment population, there were about 9.6 million children and adults with disabilities (14% of total enrollment) and 6.2 million adults age 65 and older (9% of total enrollment).

Protected Enrollment Population by State: July 2020

Exhibit 2 below shows the size of each state’s Medicaid population protected by the FFCRA continuous enrollment policy. According to CMS, between February 2020 (before the pandemic emergency was declared) and July 2020, all states experienced combined Medicaid/CHIP enrollment growth.14

The characteristics of the protected population vary from state to state, with the percentages who are children and adults with low income, children and adults with disabilities, or elderly varying considerably according to the characteristics of each state’s Medicaid plan and choices regarding coverage rules. Although all states have large numbers of affected beneficiaries across every major eligibility category, the contrasts are also notable — again, a reflection of factors ranging from state plan design to underlying population demographics.

In Utah, for example, 4 percent of the protected population is 65 or older compared to 18 percent in Maine. In Pennsylvania, 28 percent of the protected population is enrolled based on disability, compared to 8 percent in California and Hawaii. Protected children range from 32 percent to 75 percent of the enrolled population. Twenty-three states report July 2020 enrollment rates of 1 million or more, while 34 states have enrollments of 500,000 or more.

Ensuring That Enrolled Populations Do Not Erroneously Lose Coverage When the Public Health Emergency Ends

Given the relationship between Medicaid coverage and access to care, the FFCRA continuous enrollment protections, together with the Goldberg safeguards, represent essential protections.15 The CMS guidance gives states flexibility to adjust their operations to move toward normal functioning over time and offers options for simplifying the application and renewal process so as to reduce administrative burdens.

At the same time, the guidance envisions an extremely rapid return to normal operations with respect to both applications and renewals. Time pressures increase the risk of errors, especially when states are allowed to use old information and data to determine that a beneficiary is no longer eligible — for example, income from summer employment earned by working adults who later were laid off in the fall. The risk of error in the case of low-income, working-age adults may be particularly elevated given the fact that the CMS guidance expressly identifies the group as a priority for more rapid eligibility review action.

Policy Modifications That Could Make an Important Difference

One policy change to consider is a longer period for achieving normal functioning. For example, the CMS guidance appears to suggest that states will be able to meet the application timeliness standards within four months. But tight recovery performance criteria could trigger a wave of application denials and premature and erroneous case closures. As the Supreme Court observed in Goldberg, the risk of erroneous benefit expenditures is outweighed by the risk of erroneous loss or denial of basic assistance. Pandemic conditions clearly propel the equities even more strongly in the direction of averting incorrect denials and coverage losses.

A second policy option is to enhance federal Medicaid funding during a disaster recovery period, so that states have the additional resources needed for an orderly restoration of normal operations. As with the public health emergency declaration system authorized under Section 1135 of the Social Security Act, the HHS secretary could be given flexibility to tie a disaster recovery period to certain objective indicators, such as those related to population health and economic recovery. This would not be the first time Medicaid has played a role in disaster recovery; the Affordable Care Act contained an early version of such a policy, targeted to certain states.16

As states undertake recovery, an essential condition for qualifying for enhancement funding would be a disaster recovery plan that is submitted for public comment during the development phase, as well as a robust outreach strategy that can effectively inform beneficiaries of the case review process they will undergo and their rights during this process.

Ultimately, the pandemic emergency will end, and states will resume their normal Medicaid operations, including eligibility reviews and redeterminations. Given the health and health care stakes involved, when this time arrives the process should resume with caution as well as enhanced federal financial and administration support.