Changes in Household Spending

We estimate that household spending on premiums would fall $8.8 billion in 2022 even as enrollment increases. However, household spending on out-of-pocket costs for health care services (including deductibles and copayments) would increase by an estimated $0.6 billion in 2022 as access to and utilization of health care increases. Overall, households would save $8.2 billion, according to our estimates. In previous work, we found the ARPA by itself would reduce average household spending per enrollee by 23.1 percent.3

Changes in Coverage by State

If passed, this proposal would reduce the number of uninsured people in every state. We find that the largest percentage declines would occur in states that have not yet expanded Medicaid (Appendix Table 4). Declines in the proportion of uninsured people range from nearly 44 percent in Alabama to less than 6 percent in Utah.

Impact of Additional Reforms Through Administrative Action

Our estimates incorporate the effect on enrollment of administrative changes designed to increase participation, including a longer open enrollment period starting with the 2022 plan year and additional federal spending on navigators, advertising, and other types of outreach activity.

Under current law, families are generally ineligible for marketplace subsidies if a family member is offered “affordable,” worker-only coverage through an employer. The cost of covering the entire family is not considered and may be unaffordable, resulting in the so-called “family glitch.” If this policy were changed through administrative action to allow family members to become eligible for marketplace subsidies, we estimate that about 710,000 additional people would enroll in the subsidized nongroup market, most switching out of ESI. In addition, about 90,000 family members, mainly children, would newly enroll in Medicaid or CHIP as their parents seek marketplace coverage. There would be 190,000 fewer uninsured people as a result of this change. Families switching from ESI would save about $400 per person in premiums on average. These changes in coverage were estimated separately in a previous report and are not included in the numbers discussed here.4

We are not able to specifically model the provision of continuous open enrollment for people below 150 percent of FPL for this report. In our assessment, however, this provision would increase enrollment into the marketplaces by between 100,000 and 200,000 people.

Conclusion

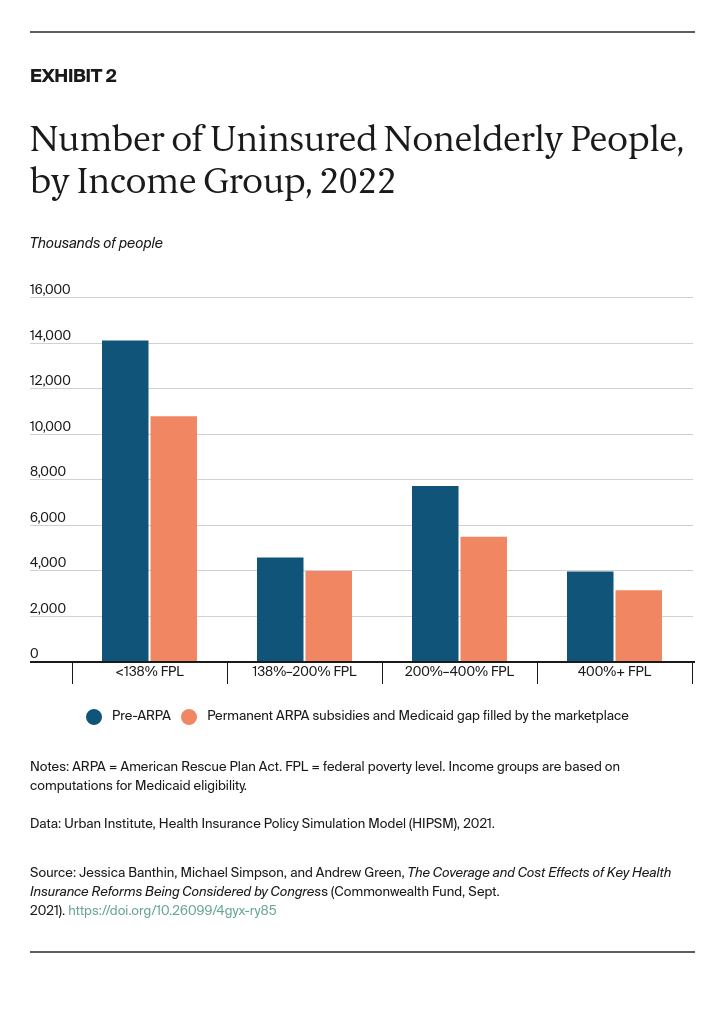

We estimate that making the enhanced ARPA subsidies permanent and filling the Medicaid coverage gap by expanding marketplace eligibility to those earning below 100 percent of FPL would have significant changes on coverage. Together, these two policies would broadly expand eligibility for marketplace subsidies, reduce the number of uninsured people especially at lower income levels, and lessen household financial burdens for health care.