Abstract

- Issue: Despite enduring racism and the need for greater racial equity, there is limited consensus among analysts, academics, and public officials on how to assess policy for its impact on racial equity. Without instructive conceptual frameworks, our ability to identify, examine, and eradicate racial inequity through health policy will be limited.

- Goal: To establish a conceptually nuanced, empirically informed, and practically useful framework for analyzing the racial equity implications of health policies.

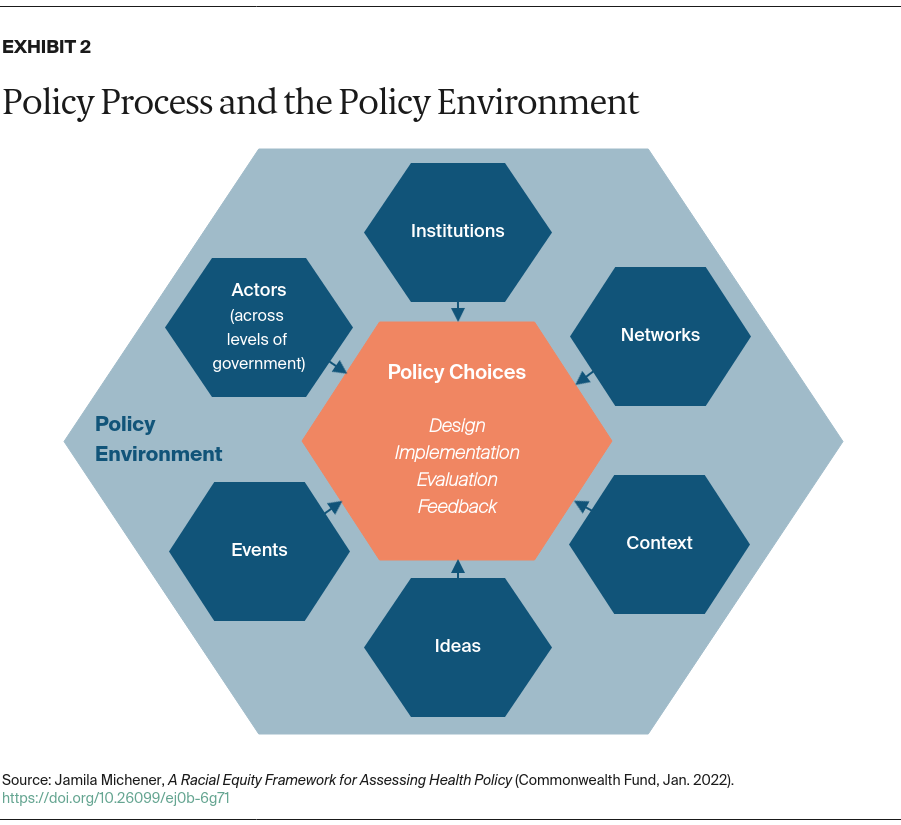

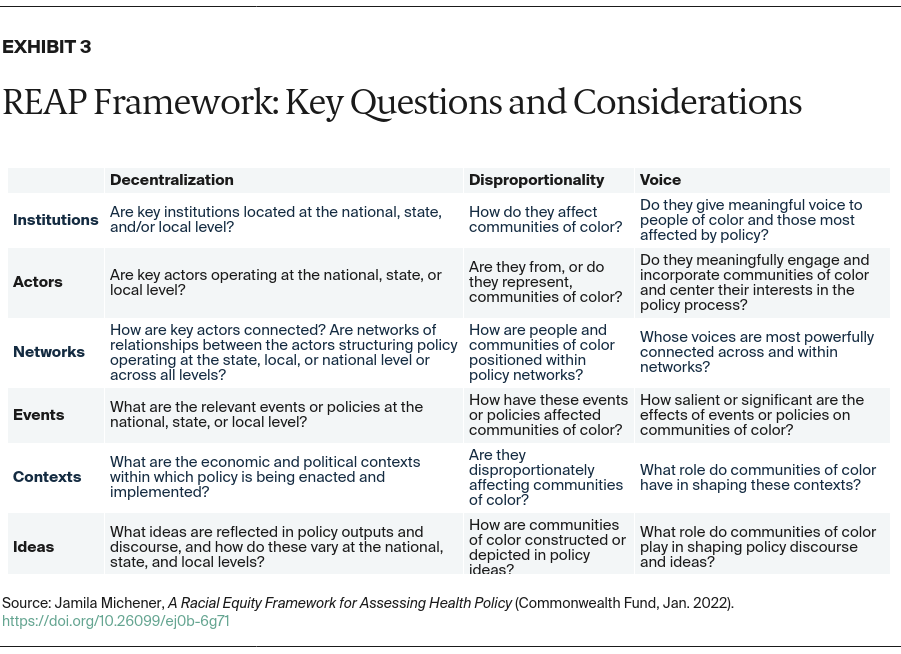

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Analysts, academics, and public officials seeking to evaluate policy through a racial equity lens should consider multiple dimensions of the policy process, including design, implementation, evaluation, feedback, and key aspects of the policy environment. We can gain important insights by systematically probing how racism is structurally produced or reproduced through each of these specific dimensions. In doing so, it is especially crucial to examine the ways that policy: 1) creates or reflects disproportionality in the allocation of benefits and burdens to racial groups, 2) operates through forms of institutional decentralization, and 3) includes or neglects the voices of racially marginalized populations. The Racial Equity and Policy (REAP) framework provides a conceptually sound, empirically grounded basis for systematically assessing racial equity in health policy.

Introduction

Racial equity took center stage in 2020, when COVID-19 and extraordinary uprisings against racial violence converged to expose the depth of racial injustice entrenched in American social, economic, and political life. In the face of a pandemic that devastated Black and Latinx communities and a faltering economy that left many of those same communities in a state of material deprivation, antiracism emerged as a renewed clarion call. The conversation around racial justice has aptly stressed the centrality of structural racism — racial inequity that is “produced and reproduced by laws, rules, and practices, sanctioned and even implemented by various levels of government.”1

Public policy is among the most enduring and powerful structures shaping racial inequity in health.2 Both historically and contemporarily, public policies have been instruments through which government has created, maintained, and exacerbated racial disparities through domains such as housing, healthcare, and welfare.3 Of course, policy has also been employed to reduce and redress racial disparities.4 Altogether, the trajectory of U.S. public policy vis-à-vis racism has not been uniform, progressive, or linear.

This issue brief presents a framework for systematically assessing health policy through the lens of racial equity.

Medicaid’s Centrality in Assessing Equity

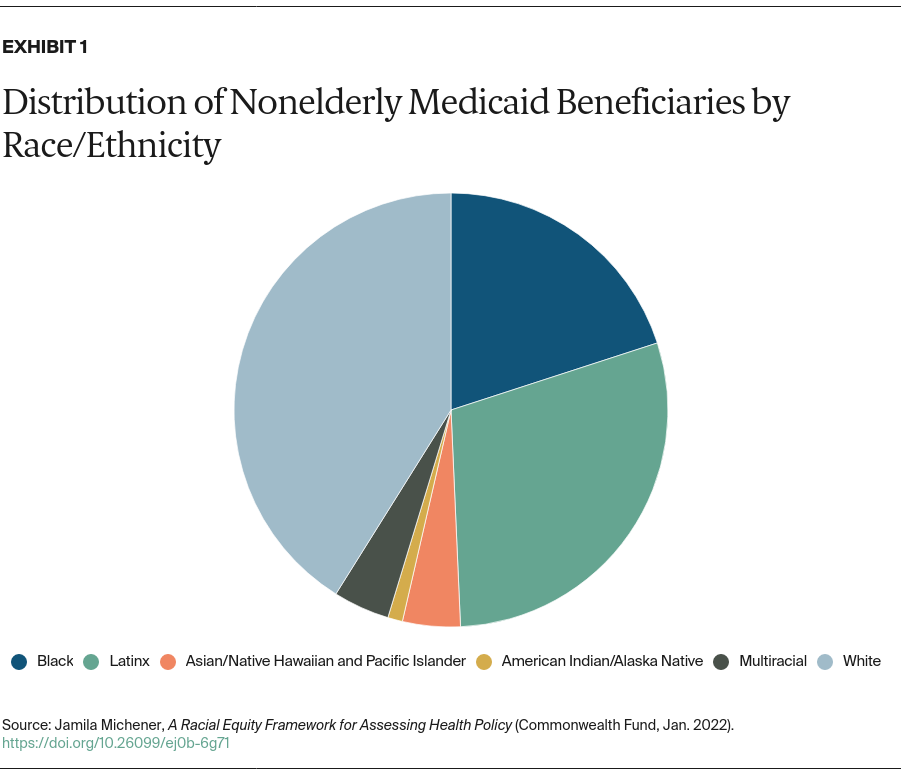

Given its immense footprint across the U.S. health care system, Medicaid is an obvious choice for applying a framework intended to have broad applicability to public policy. With over 80 million enrollees, Medicaid is the largest public health insurance provider in the United States. It accounts for over 28 percent of all spending by states and more than 9 percent of federal outlays.5 The racial composition of people covered by Medicaid further underscores the program’s importance in efforts to address racial equity concerns in health care: nationwide, 30 percent of nonelderly Medicaid beneficiaries are Latinx, 20 percent are Black, and nearly 10 percent comprise additional minoritized racial or ethnic groups, including Asian/Native Hawaiian, American Indian/Alaska Native, and people who identify as multiracial (Exhibit 1).6

On a state level, Black, Latinx, Asian, Native, and multiracial Americans compose a majority of Medicaid beneficiaries in 25 states. In many states, people of color account for large majorities, including in Hawaii (87%), California (79%), Texas (79%), Georgia (68%) Florida (65%), and New York (64%).7