Abstract

- Issue: The recently passed Inflation Reduction Act extended enhanced tax credits for health insurance premiums first introduced by the American Rescue Plan Act. This legislation could serve as a foundation for additional reforms to further expand coverage and make health care more affordable.

- Goal: Analyze the financial impact for U.S. households of a proposed health reform package that would: 1) fill the Medicaid coverage gap in states that have not expanded Medicaid eligibility; 2) reduce the employer affordability threshold; 3) add a $10 billion reinsurance fund; 4) increase the federal Medicaid matching rate in expansion states; and 5) reduce cost sharing in marketplace plans.

- Methods: Using the Urban Institute’s Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model, we assess changes in household spending on health care, in dollars and as a percentage of income.

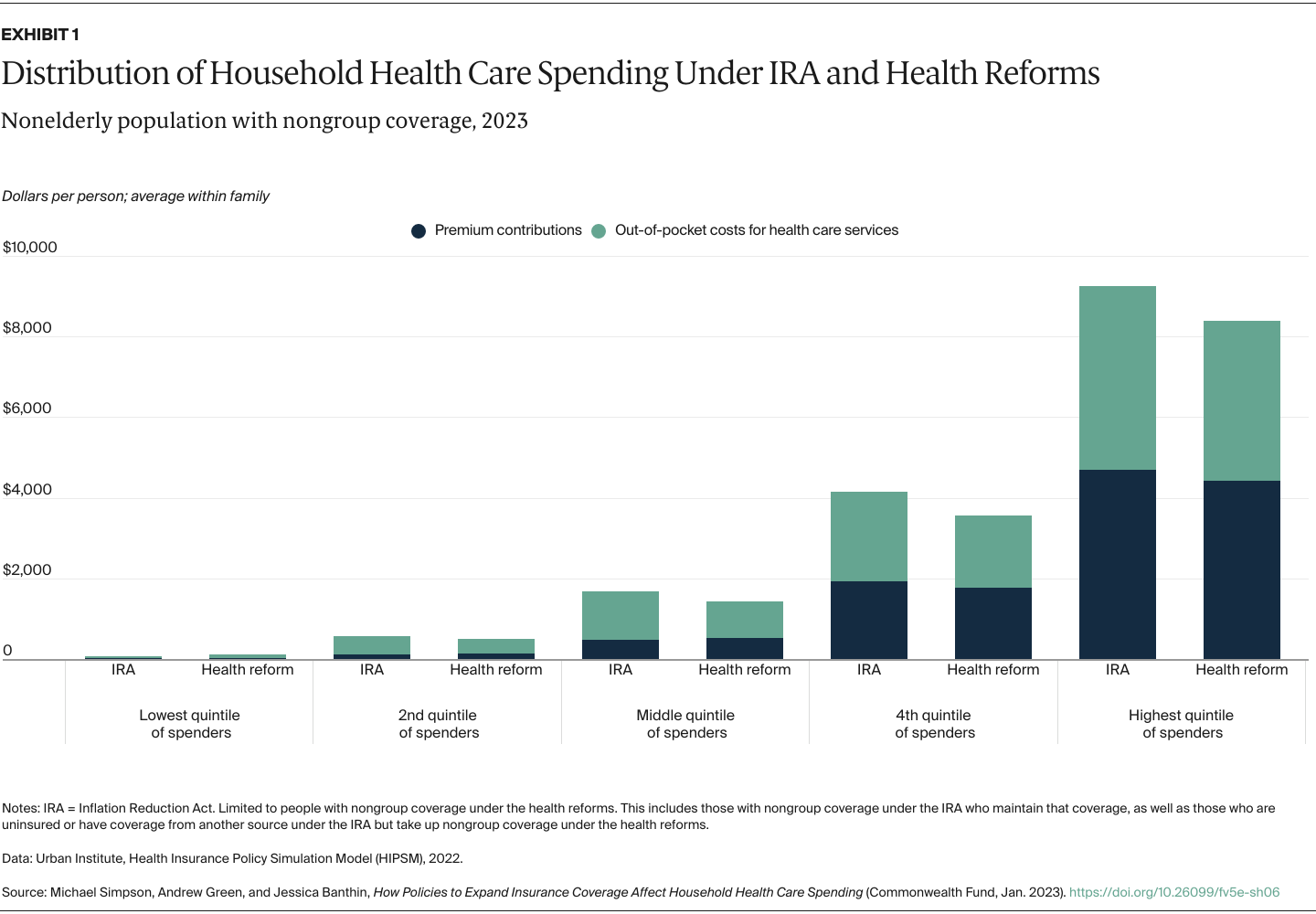

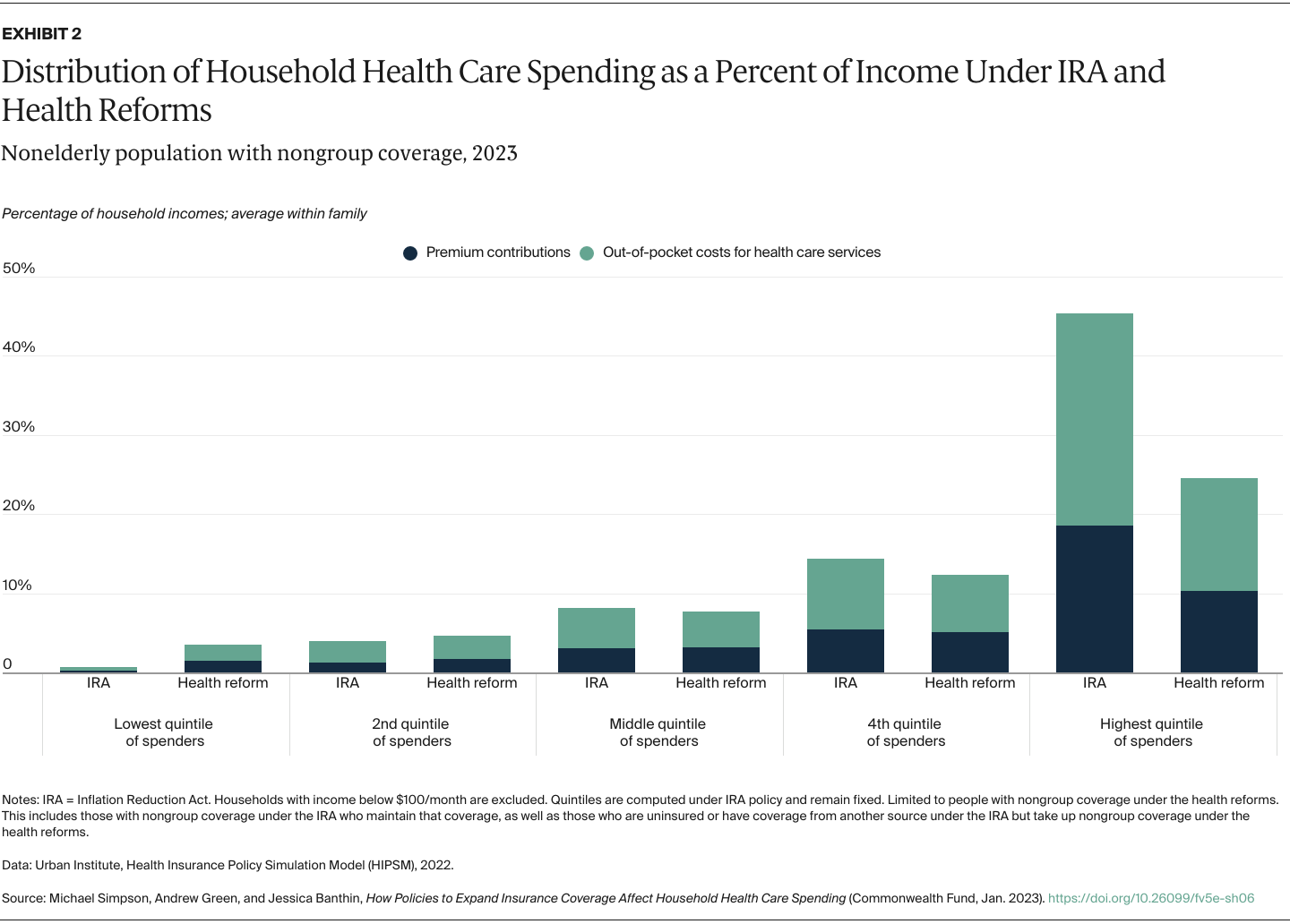

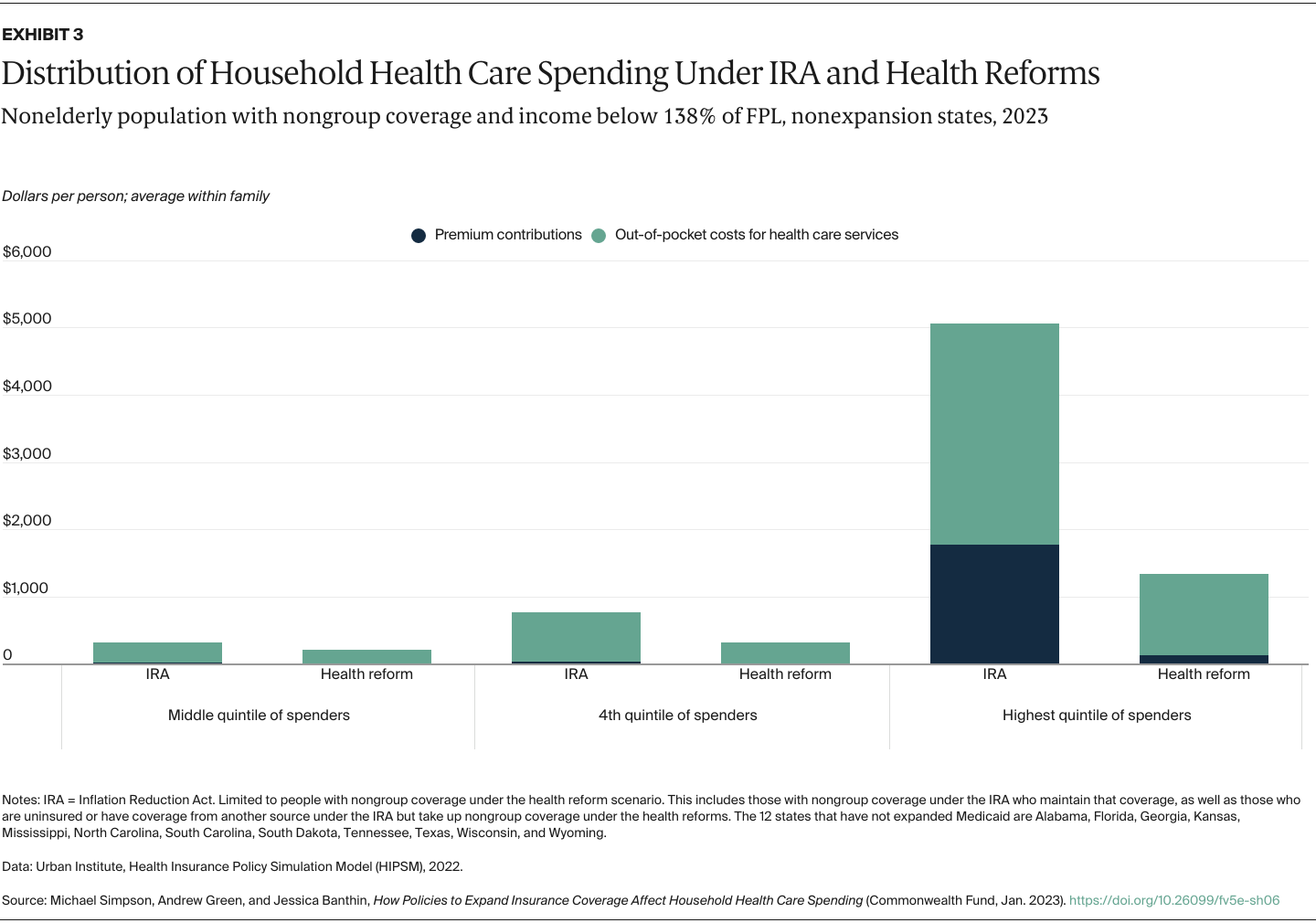

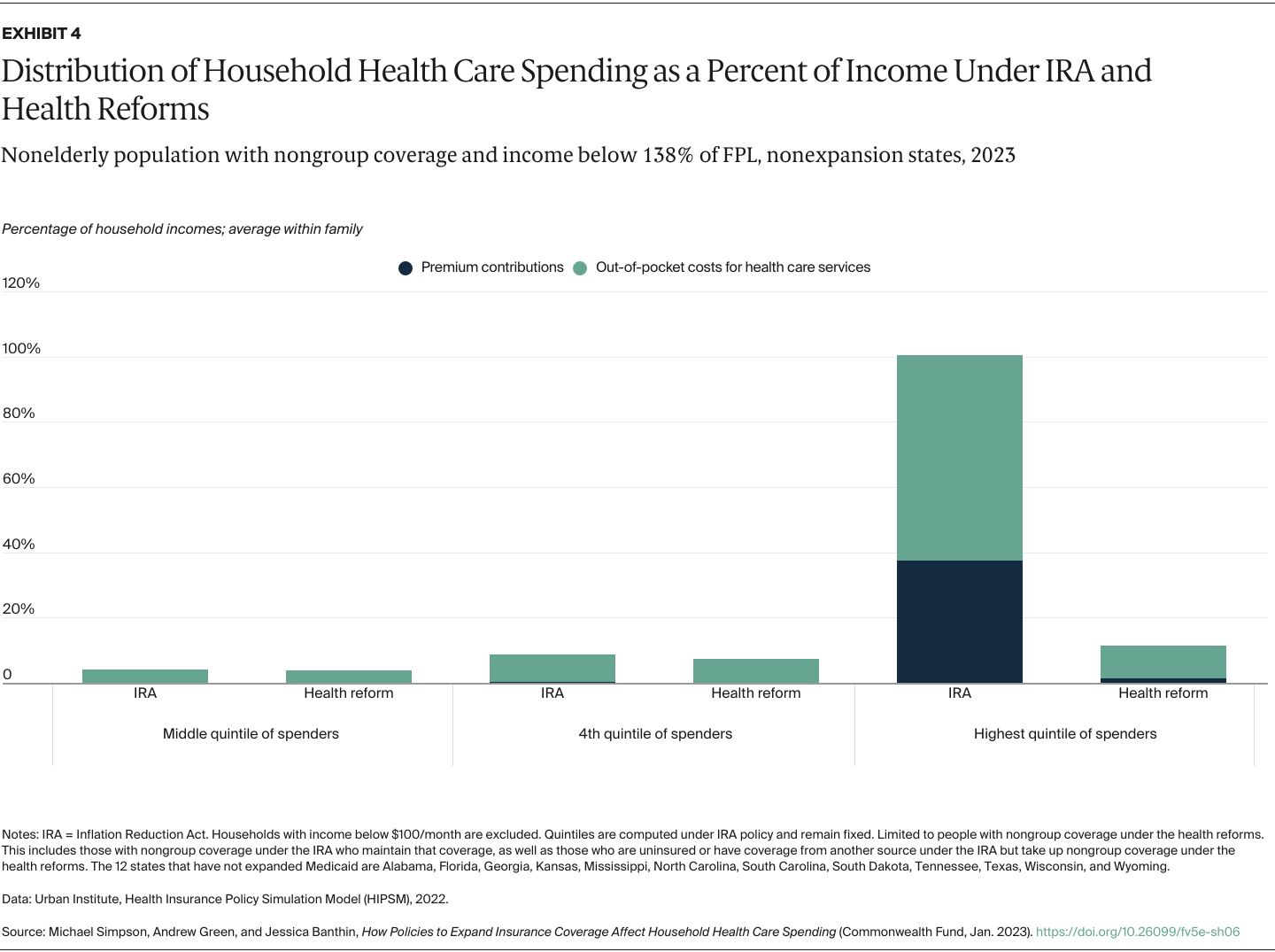

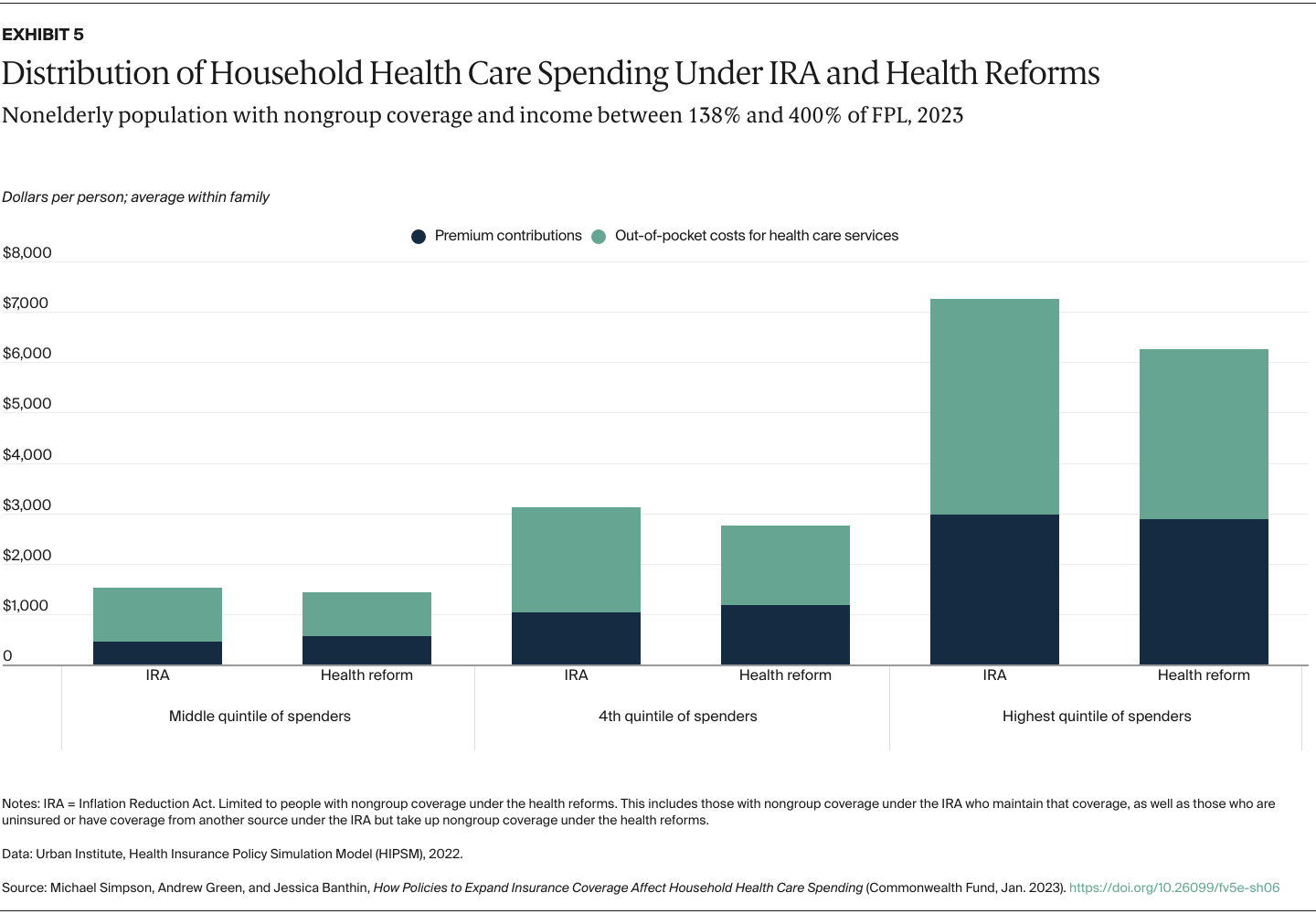

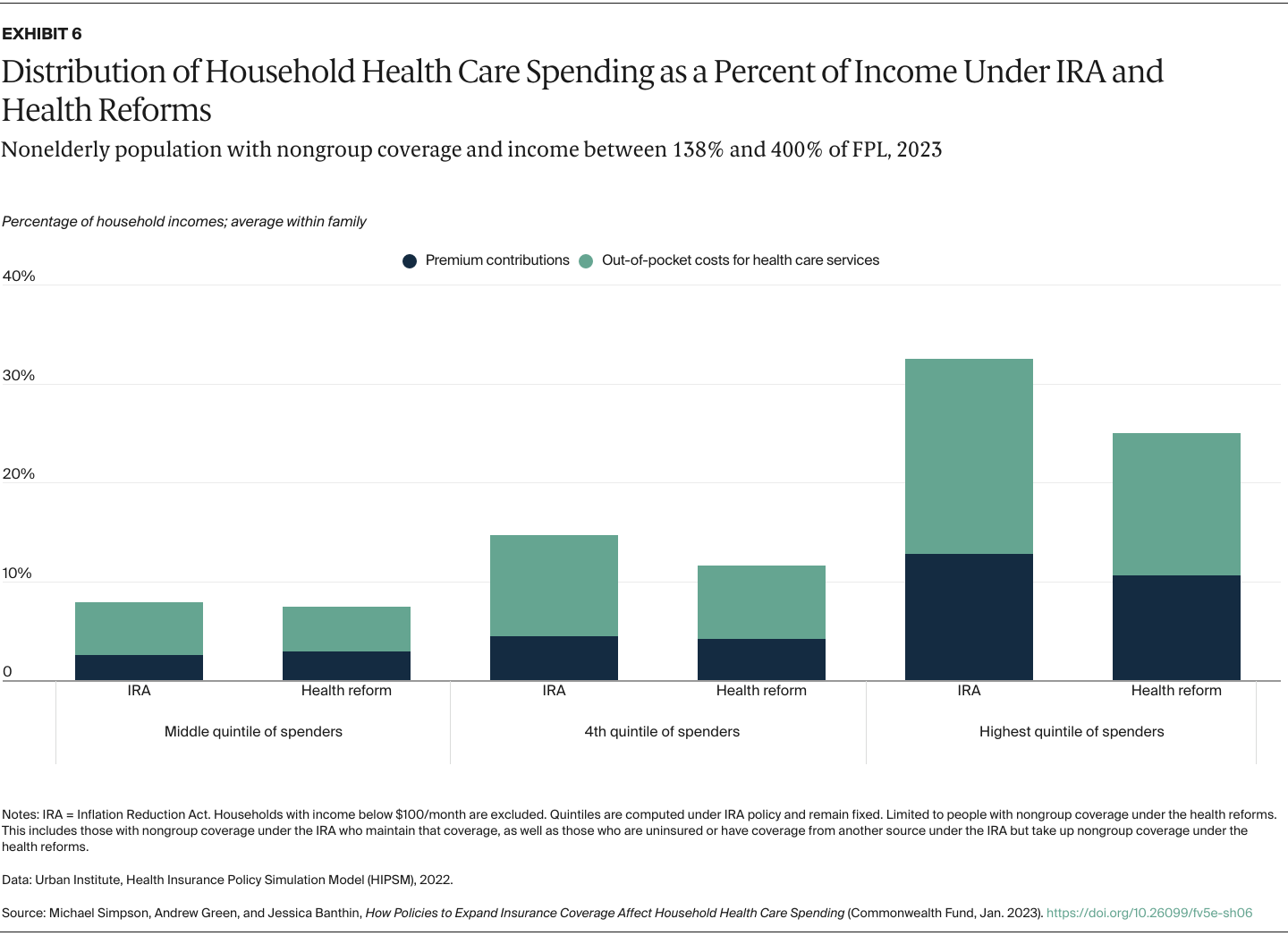

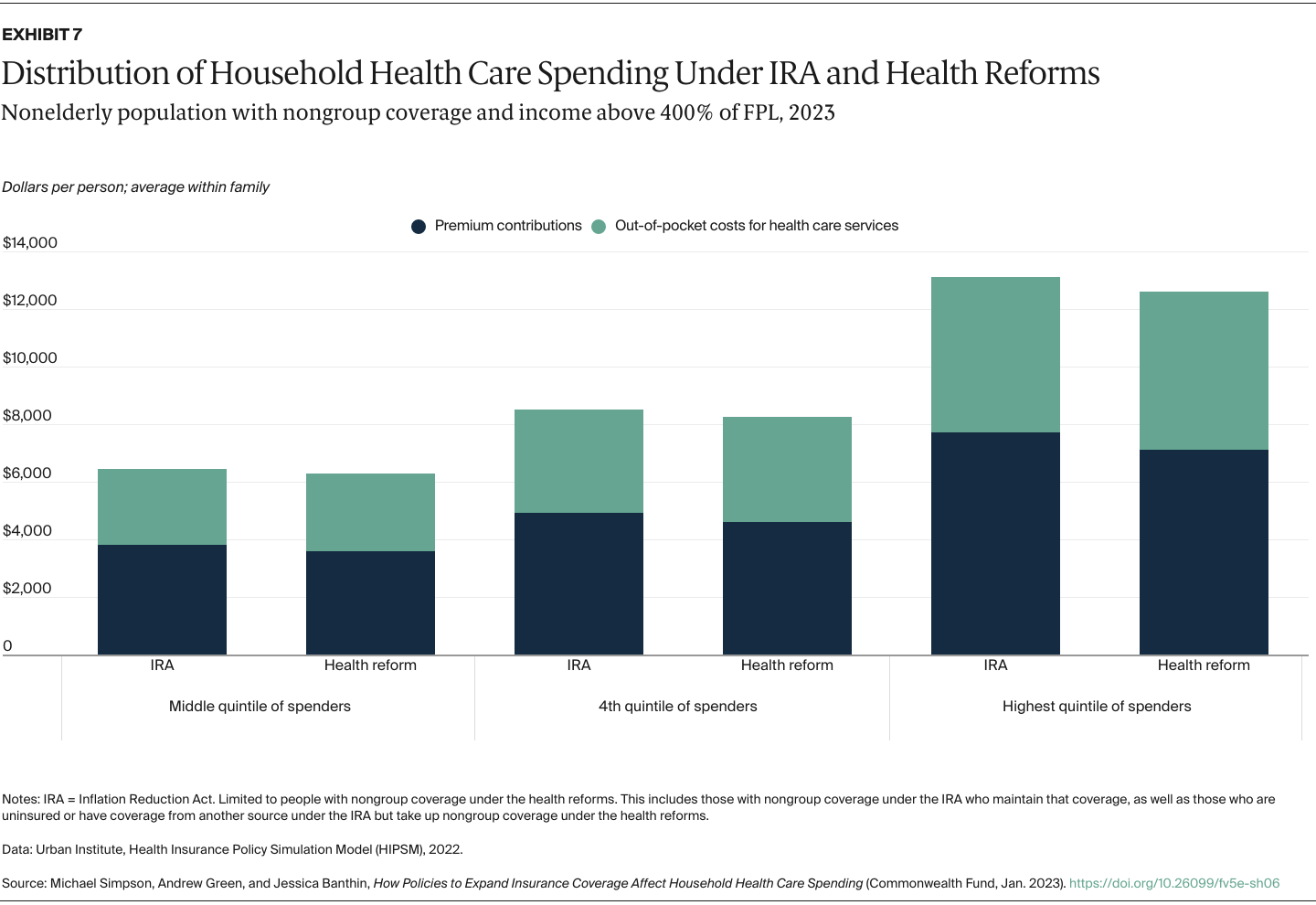

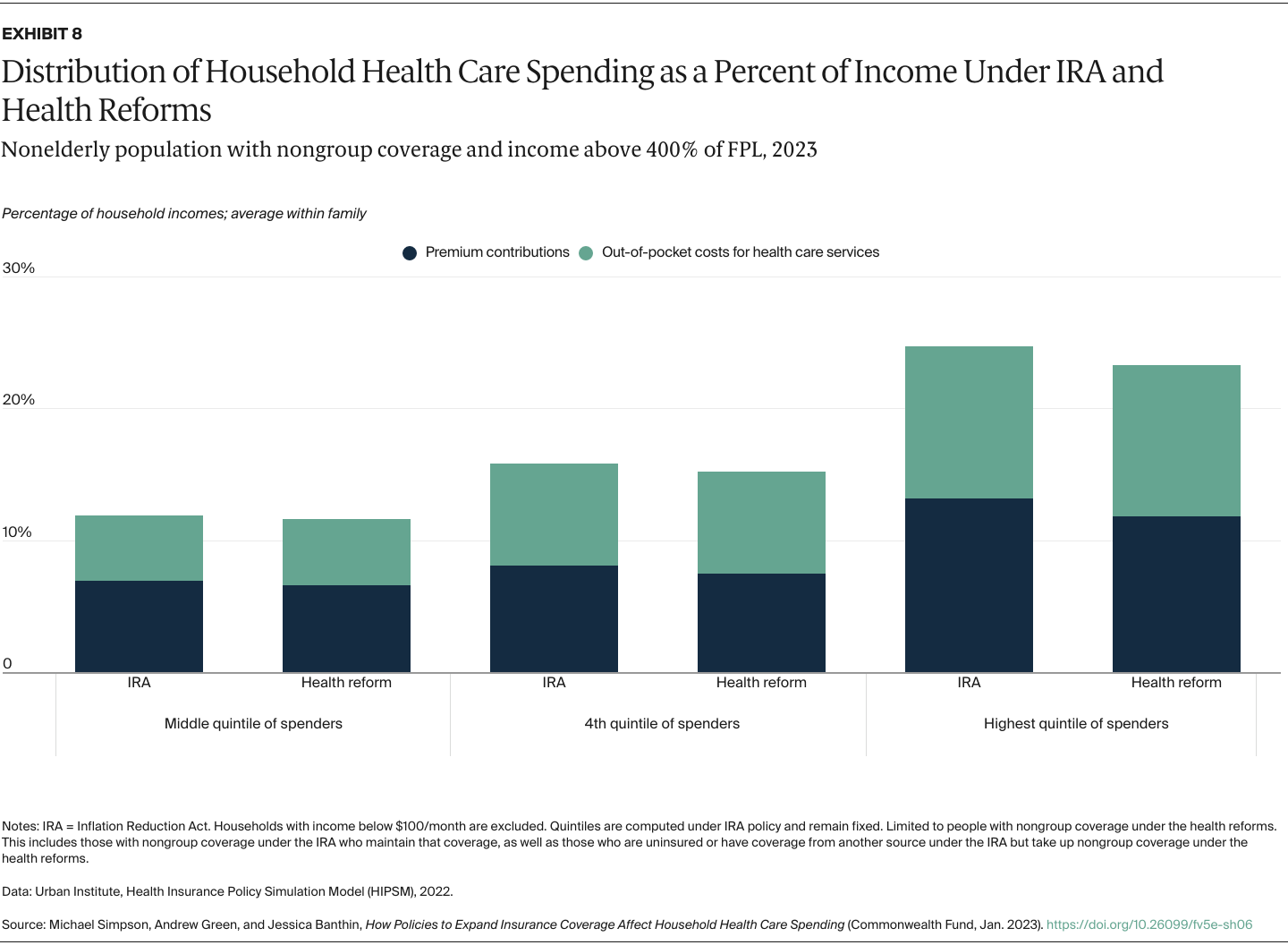

- Key Findings and Conclusions: The reforms reduce health spending for targeted households. These reductions would be greatest for households spending the most on health care, both in dollars and as a share of income. Filling the Medicaid coverage gap would lead to substantial savings for low-income households in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Households also see significant savings from enhanced cost-sharing subsidies.

Introduction

Enhanced premium tax credits — first introduced under the American Rescue Plan Act and extended by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — substantially reduced marketplace coverage costs and led to a significant increase in enrollment.1 However, these tax credits leave out many people also needing better access to affordable coverage, particularly those who live in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid eligibility as permitted under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Additional policies are needed to address these gaps and further lower household spending on copayments, deductibles, and other cost sharing.

The impact of health reforms is usually measured by its effects on aggregate costs and coverage, such as the number of uninsured. The distributional impact on household financial burdens is not captured consistently in standard measures, leaving critical benefits of new health policies unknown.

Using a comprehensive measure of household financial burden, we measured the impact of a reform package that builds on IRA tax credits on the distribution of household spending on health care. The proposed reforms we model would:

- Make marketplace premium subsidies available to low-income people in the 12 states that have not expanded Medicaid, which would benefit people with incomes above traditional Medicaid eligibility levels and below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), and eliminate the employer offer firewall — or the threshold above which employer coverage is deemed unaffordable — for people below 138 percent of FPL.

- Enhance and fund cost-sharing reduction subsidies that reduce copayments, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket payments for people with low incomes.

- Introduce policies to lower the employer coverage firewall to 8.5 percent of income, fund $10 billion in reinsurance nationwide, and increase the federal match rate for Medicaid in nonexpansion states.2

We capture changes in household spending on both premium contributions and expected out-of-pocket spending for health care services because of cost-sharing requirements such as copayments and deductibles. We determine average spending per family member from total household spending so we can look at the distribution of individuals without regard to household size. As health spending is highly skewed — many people spend little while a relative few spend large amounts — we present our results by spending quintiles instead of a simple average to show how reforms would affect those using more health services. Our results are shown both in dollars and as shares of family income to better capture the burden of health care spending on low-income families, who tend to spend a larger share of income on health care costs.