A child’s health, ability to participate fully in school, and capacity to lead a productive, healthy life depend on access to preventive and effective health care—starting well before birth and continuing throughout early childhood and adolescence. Since healthy children are key to the well-being and economic prosperity of families and society, investing in child health has long been a high priority for federal and state policy. This State Scorecard on Child Health System Performance, 2011, finds that federal action to extend insurance to children has made a critical difference in reducing the number of uninsured children across states and maintaining children’s coverage during the recent recession. However, the report also finds that where children live and their parent’s incomes significantly affect their access to affordable care, receipt of preventive care and treatment, and opportunities to survive past infancy and thrive. Better and more equitable results will require improving the quality of children’s health care across the continuum of their needs as well as holding health care systems accountable for preventing health problems and promoting health, not just caring for children when they are sick or injured.

The Scorecard’s findings on children’s health insurance attest to the pivotal role of federal and state partnerships. Until the start of this decade, the number of uninsured children had been rising rapidly as the levels of employer-sponsored family coverage eroded for low- and middle-income families. This trend was reversed across the nation as a result of state-initiated Medicaid expansions and enactment and renewal of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Currently, Medicaid, CHIP, and other public programs fund health care for more than one-third of all children nationally. Children’s coverage has expanded in 35 states since the start of the last decade and held steady even in the middle of a severe recession. At the same time, coverage for parents—lacking similar protection—deteriorated in 41 states.

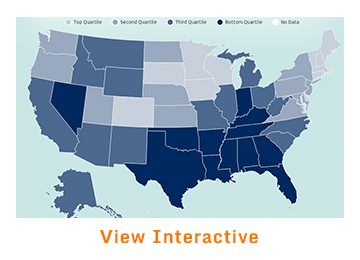

With the goal of identifying opportunities to improve, this Scorecard examines state performance on 20 key health system indicators for children clustered into three dimensions: access and affordability, prevention and treatment, and potential to lead healthy lives. It also examines state performance by family income, insurance status, and race/ethnicity to assess the equity of the child health care system—the fourth dimension of performance. The analysis ranks states and the District of Columbia on each indicator and the four dimensions. The analysis finds wide variation in system performance, with often a two- to threefold difference across states, as illustrated in Exhibit 1. Benchmark levels set by leading states show there are abundant opportunities to improve health system performance to benefit children. If all states achieved top levels on each dimension of performance, over 5 million more children would be insured and 10 million more children would receive at least one medical and dental preventive care visit per year. Eight hundred thousand more children ages 19 to 35 months would be up to date on all recommended doses of six key vaccines, and nearly 370,000 fewer children with special health care needs would have problems getting referrals to specialty care services. Likewise, nearly 9 million additional children would have a medical home to help coordinate their care.

The 14 states in the top quartile of the overall performance ranking—Iowa, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Hawaii, Minnesota, Connecticut, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Kansas, and Washington—often perform well on multiple indicators and across dimensions (Exhibit 2). At the same time, the Scorecard finds that even the leading states have opportunities to improve: no state ranks in the top half of the performance distribution on all indicators. At the other end of the spectrum, states in the bottom quartile generally lag in multiple areas, with worse access to care, lower rates of recommended prevention and treatment, poorer health outcomes, and wide disparities related to income, race/ethnicity, and insurance status.

Throughout, the findings underscore the importance of policy action to sustain children's access to care in the midst of rising health care costs and financial stress on families. Access to care must be coupled with statewide initiatives and community efforts to improve health care system performance for children.

The State Scorecard on Child Health System Performance, 2011, finds that some states do markedly better than others in promoting the health and development of their youngest residents, and in ensuring that all children are on course to lead healthy and productive lives. As states, clinicians, and hospitals prepare to implement health reforms, the Scorecard provides a framework to take stock of where they stand today and what they could gain by reaching and raising benchmark performance levels.

The findings reveal crucial areas in which comprehensive federal, state, and community policies are needed to improve child health system performance for all families. States that invest in children’s health reap the benefits of having children who are able to learn in school and become healthy, productive adults. Other states can learn from models of high performance to shape policies that ensure all children are given the opportunity to lead long, healthy lives and realize their potential.

Greater investment in measurement and data collection at the state level could enrich understanding of variations in child health system performance. For many dimensions, only a limited set of indicators is available. Moreover, there is often a time lag in the availability of data. National surveys of children’s health care are conducted at four-year intervals, for example. Hence, a large number of indicators discussed in this Scorecard date from 2007. The indicators of child health care quality presented here are also largely parent-reported. The collection of more robust clinical data on children’s health care quality is integral to future state and federal child health policy reform and could modify the state rankings provided in this report. The CHIP program reauthorization has begun to lead the way by creating a set of standardized quality measures for use by CHIP, Medicaid, and health plans. The availability of core measures and information on community-level variation will enable states to learn from innovative models. Work under way in many states as well as efforts supported by CHIP and the Affordable Care Act should lay a foundation for public and private action.

HIGHLIGHTS

Children's health insurance coverage has expanded in many states, while parents' coverage has eroded. Yet the number of uninsured children continues to vary widely across states.

Currently 10 percent of children are uninsured nationally, and the uninsured rate for children exceeds 16 percent in three states. In contrast, 19 percent of parents are uninsured nationally, and there are nine states in which 23 percent or more of parents are uninsured. The difference between children’s and parents’ coverage rates reflects federal action taken early in the last decade to insure children, as well as continued federal support for children’s coverage. There is no national standard for coverage of parents, however poor. Still, the percent of uninsured children continues to vary widely across states, ranging from a low of 3 percent in Massachusetts to a high of 17 percent to 18 percent in Nevada, Florida, and Texas. The range underscores the importance of state as well as federal action to ensure access and continuity of care.

The passage of the Affordable Care Act will—for the first time—provide health insurance to all low- and middle-income families. To achieve this, the law will expand Medicaid to low-income parents as well as childless adults with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, beginning in 2014. This represents a substantial change in Medicaid’s coverage of adults. The law will also assist families with low and moderate incomes to purchase coverage through insurance exchanges and tax credits. These policies will directly benefit children as families gain financial security, and parents’ health improves.

Across states, the extent to which children have access to care is closely related to their receipt of preventive care and treatment. Yet insurance does not guarantee receipt of recommended care or positive health outcomes.

Seven of the 13 leading states in the access and affordability dimension also rank among the top quartile of states in terms of prevention and treatment. Children in states with the lowest uninsured rates are more likely to have a medical home and receive preventive care or referrals to needed care than children in states with the highest uninsured rates. While insurance matters, good care and outcomes are also a function of a well-functioning health care delivery system. Securing coverage and access to affordable care for families is only a first step to ensure that children obtain essential care that is well coordinated and patient-centered.

Children's access to care, health care quality, and health outcomes vary widely across states.

The Scorecard findings show that where a child lives has an impact on his or her potential to lead a healthy life into adulthood. States vary widely in their provision of children’s health care that is effective, coordinated, and equitable. This variability extends to states’ ability to ensure opportunities for children to achieve optimal health.

There is a twofold or greater spread between the best and worst states across important indicators of access and affordability, prevention and treatment, and potential to lead healthy lives. The performance gaps are particularly wide on indicators assessing developmental screening rates, provision of mental health care, hospitalizations because of asthma, prevalence of teen smoking, and mortality rates among infants and children. Lagging states would need to improve their performance by 60 percent on average to achieve benchmarks set by leading states.

If all states were to improve their performance to levels achieved by the best states, the cumulative effect would translate to thousands of children’s lives saved because of more accessible and improved delivery of high-quality care. In fact, improving performance to benchmark levels across the nation would mean: 5 million more children would have health insurance coverage, nearly 9 million children would have a medical home to help coordinate care, and some 600,000 more children would receive recommended vaccines by the age of 3 years.

Leading states—those in the top quartile—often do well on multiple indicators across dimensions of performance; public policies and state/local health systems make a difference.

The 14 states at the top quartile of the overall performance rankings generally ranked high on multiple indicators and dimensions. In fact, the five top-ranked states—Iowa, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire—performed in the top quartile on each of the four dimensions of performance. Many have been leaders in improving their health systems by taking steps to cover children or families, promote public health, and improve care delivery systems.

|

IOWA’S COMPREHENSIVE PUBLIC POLICIES MAKE A DIFFERENCE FOR CHILDREN’S HEALTH Iowa, tied in first place with Massachusetts in terms of overall children’s health system performance, has had a long-standing commitment to children. In the past decade, the state paid particular attention to the needs of its youngest residents, from birth to age 5. After piloting a variety of programs in the early 1990s to identify and serve at-risk children and families, the Iowa legislature established a statewide initiative to fund "local empowerment areas" across the state. The partnerships among clinicians, parents, child care representatives, and educators seek to ensure children receive needed preventive care. State leaders have focused on child health outcomes by promoting the federal Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program. In 1993, an EPSDT Interagency Collaborative was formed with a fourfold purpose: to increase the number of Iowa children enrolled in EPSDT; to increase the percentage of children who receive well-child screenings; to ensure effective linkages to diagnostic and treatment services; and to promote the overall quality of services delivered through EPSDT. As a result of these efforts, the statewide rate of well-child screenings rose from 9 percent to 95 percent in just over five years. Iowa has also been making strides in providing high-quality mental health care for children. Its 1st Five Healthy Mental Development Initiative focuses on a child’s first five years. The state-led initiative helps private providers to develop a sound structure for assessing young children’s social and developmental skills. Under the 1st Five system, a primary care provider screens children and their caregivers when they come in for a visit; if a concern is identified, the provider notifies the 1st Five Child Health Center. The center’s care coordinator then contacts the family to link them to appropriate services in the community or help coordinate referrals. Iowa also has expansive policies in place to ensure children have health care coverage. The State Children’s Health Insurance Program covers all children under age 19 in families with income levels up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Children ages 6–18 whose family income is between 100 percent and 133 percent of FPL and infants whose family income is between 185 percent and 300 percent of FPL are covered through an expansion of Medicaid. Meanwhile, children in families with income from 133 percent to 300 percent of FPL are covered through private insurance, in a program known as Healthy and Well Kids in Iowa (hawk-i). Iowa contracts with private health plans to provide covered services to children enrolled in the hawk-i program, with little or no cost-sharing for families. Recently, in the spring of 2010, hawk-i implemented a dental-only plan. Iowa’s innovative policies and public–private partnerships to improve children’s health care serve as evidence-based models that other states can follow to move toward a higher-performing child health system. For more information see N. Kaye, J. May, and M. K. Abrams, State Policy Options to Improve Delivery of Child Development Services: Strategies from the Eight ABCD States (Portland, Maine, and New York: National Academy for State Health Policy and The Commonwealth Fund, Dec. 2006); and S. Silow-Carroll, Iowa’s 1st Five Initiative: Improving Early Childhood Developmental Services Through Public–Private Partnerships, (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Sept. 2008). |

In contrast, states at the bottom quartile of overall child health system performance lagged well behind the leaders on multiple indicators of performance. These states had rates of uninsured children and parents that were, on average, more than double those in the top quartile of states. Reflecting the strong association between access to care and the quality and continuity of care, children in the lowest-quartile states were among the least likely to receive routine preventive care visits or mental health services when needed, or to report having a primary care practice that serves as a medical home to provide care and care coordination. Notably, rates of developmental delays and infant mortality are more than 20 percent to 30 percent higher, respectively, in the lowest-quartile states compared with top-quartile states.

These patterns indicate that public policies, as well as state and local health systems, can make a difference to children’s health and health care. But socioeconomic factors also play a role—underscoring the importance of federal and state policies in areas with high rates of poverty.

Regional performance patterns provide valuable insight.

The Scorecard revealed regional patterns in child health system performance. Across dimensions, states in New England and the Upper Midwest often rank in the highest quartile of performance, whereas states with the lowest rankings tend to be concentrated in the South and Southwest. Yet within any region, there are exceptions. For example, West Virginia and Tennessee face high rates of poverty, unemployment, and disease yet rank in the top half of performance on indicators of children's health. West Virginia does exceptionally well in ensuring access and high-quality care for its most vulnerable children, ranking fifth in terms of equity. Alabama is in the top quartile for children's insurance, with nearly 94 percent insured. And North Carolina leads in providing developmental screening for young children.

Leading states as well as those that outperform neighboring states within a region have often made concerted efforts to improve through coverage and quality improvement initiatives. Learning about these initiatives can offer insights for other states, particularly those starting with similar health systems or resource constraints.

There is room to improve in all states. Even in the best states, performance falls short on at least some indicators and state averages are below what should be achievable.

All states have room to improve. None ranked in the top half of the performance distribution across all indicators. For some indicators, performance was not outstanding even in the high-ranked states. For example, North Carolina ranked first in terms of screening children for developmental or behavioral delays, yet more than half of children in the state were not screened, based on parents’ reports. Nearly a third of children did not have access to care meeting the definitions of a medical home, even in the top-ranked state in this indicator. Conversely, states that performed poorly overall outperformed higher-ranking states on some indicators. There is value in learning from best practices around the nation.

Rising rates of childhood overweight or obesity plague all states. Moreover, many children live with oral health problems that could be addressed with timely, affordable access to effective preventive dental care and treatment. Even in the top-ranked state on this indicator, Minnesota, one of five children has oral health problems such as tooth decay, pain, or bleeding gums.

Inequitable care and outcomes by insurance status, income, and race/ethnicity remain a large concern. Uninsured, low-income, and minority children have less than equal opportunity to thrive in nearly all states. Yet in some higher-performing states, these vulnerable children do nearly as well as the national average and rival performance levels achieved for children in higher-income families, indicating that gains in statewide performance are achievable by focusing on the most vulnerable children.!!!PAGE BREAK!!!

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Overall, the Scorecard indicates that multiple dimensions of health system performance for children are related. Reducing high rates of admission to the hospital or emergency department for children’s asthma requires primary care resources and, potentially, public health interventions to reduce the triggers of asthma attacks. Poor access undermines the quality of care and drives up costs for complications that could have been prevented. High rates of infant mortality are related to high rates of low-birthweight babies, which in turn are related to the mother’s health and care during pregnancy. Promoting healthy family behaviors in medical and community settings is a key component to preventing unnecessary deaths, chronic conditions, and complications among both children and adults. Ensuring well-coordinated, high-quality care, including preventive care, will require physicians and hospitals to work together with families and share accountability for children’s health. Clinical care systems also need to work hand in hand with public health professionals and community-based groups to implement programs and evaluate progress toward achieving population health goals.

The report indicates that federal action is essential to support state and community efforts for children. This year will mark the second anniversary of the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA), an event that affirmed the national commitment to expanding coverage of children in low- and modest-income families. The federal stimulus bill strengthened this support by increasing federal matching rates for Medicaid to enable states to maintain these programs in the midst of a severe recession.

By expanding coverage to adults, as well as to children, the Affordable Care Act will for the first time ensure that coverage will be accessible and affordable for families in all states. Insurance expansion to parents will enhance children’s health and financial security, based on studies that find that children are more likely to be enrolled in coverage and receive care when their parents are also insured and have the ability to pay for care.

Health system provisions of the Affordable Care Act will improve primary care in all states by enhancing Medicaid as well as Medicare payments for primary care and encouraging physician practices to serve as medical homes. Provisions for support of pediatric accountable care organizations through state Medicaid programs will promote innovative, integrated care systems that emphasize the "triple aim" of better health, better care experiences, and slower cost growth.

Overall, the State Scorecard on Child Health System Performance, 2011, reveals that—in the period leading up to the enactment of federal health care reforms—there were wide geographic variations in health care system performance for children and ample opportunities to improve. The gaps between benchmarks set by top-performing states and average performance, as well as the wide range of performance across the nation, indicate that the United States is failing to ensure that all children receive the timely, effective, and well-coordinated care they need for their health and development. This Scorecard documents geographic variations in risk factors such as developmental delay and obesity, pointing out the need for comprehensive medical and public health interventions to support children and their families in obtaining needed services and adopting healthy lifestyles.

While top-performing states provide examples for other states, the fact remains that none of the states performed well on all indicators and many performed at levels that are far from optimal—highlighting the need for systemic change. Compared with other states, poorly performing states often have fewer resources, larger uninsured populations, and greater socioeconomic challenges that may limit their capacity for improvement. The formula for determining federal funding of state Medicaid programs recognizes this inequality among states. Likewise, the recent economic recession illustrates how federal funding plays a countercyclical role to help all states maintain coverage during times of fiscal duress. The Affordable Care Act will continue this precedent with a flow of resources into states with the highest rates of poverty.

Hence, a coherent set of national and state policies is essential to sustain improvements in children’s health care across the nation. Federal health reform provides the common foundation on which states can build to help eliminate the variations, gaps, and disparities in children’s coverage and care documented in this Scorecard. Notably for children, the Affordable Care Act strengthens and depends on successful federal–state partnership—not only to expand coverage but also to improve the quality of care for children.

State action and leadership will be essential to implement reforms effectively and to support initiatives tailored to specific state circumstances. Actions states can take include:

- Ensure continuous insurance coverage for all children by making it easy to sign up for and keep insurance for children and families. This includes: removing administrative barriers, streamlining applications, and coordinating public and private coverage for lower-income families through health insurance exchanges.

- Strengthen Medicaid and CHIP provider networks with support of care systems that provide high-quality care and superior outcomes for children and their families.

- Align provider incentives to promote access and high-value care. This includes participating in multipayer initiatives that support care coordination in primary care medical homes, which can help reduce hospitalizations and emergency department use.

- Promote accountable, accessible, patient-centered, and coordinated care for children by participating in various Medicaid pilots and demonstrations as well as grant opportunities to create integrated care delivery models to improve care in local communities.

- Support information systems to inform and guide efforts to improve quality, health outcomes, and efficiency. This includes: adoption of pediatric quality measures to report on CHIP performance; expanded use of children's outcome measures, including tracking potentially preventable rates of hospital and emergency department use; and promoting effective use of health information technology with exchange across sites of care to enhance coordination and safety and to support clinicians caring for children and their families.

- Participate in statewide initiatives, including support for shared resources such as after-hours care and community health teams, to provide the accountable leadership and collaboration essential to set and achieve goals for children's health.

With costs rising faster than incomes and pressuring families and businesses, effective public policies as well as improvement efforts within care systems are needed. Realizing the potential of recent federal reforms that focus on children will require a team effort, calling upon both community-level interventions and effective state policies. One of the strengths of the U.S. health care system is its examples of excellence and innovation. Ensuring that all children have the opportunity to thrive through a health care system that responds to their needs will depend on learning from these diverse experiences and spreading successful improvement strategies. Investing in children’s health yields long-term payoffs: healthy children are better able to learn in school and are more likely to become healthy, productive adults. Individuals, families, and society as a whole benefit from reduced dependency and disability, a healthier future workforce, and a stronger economy.