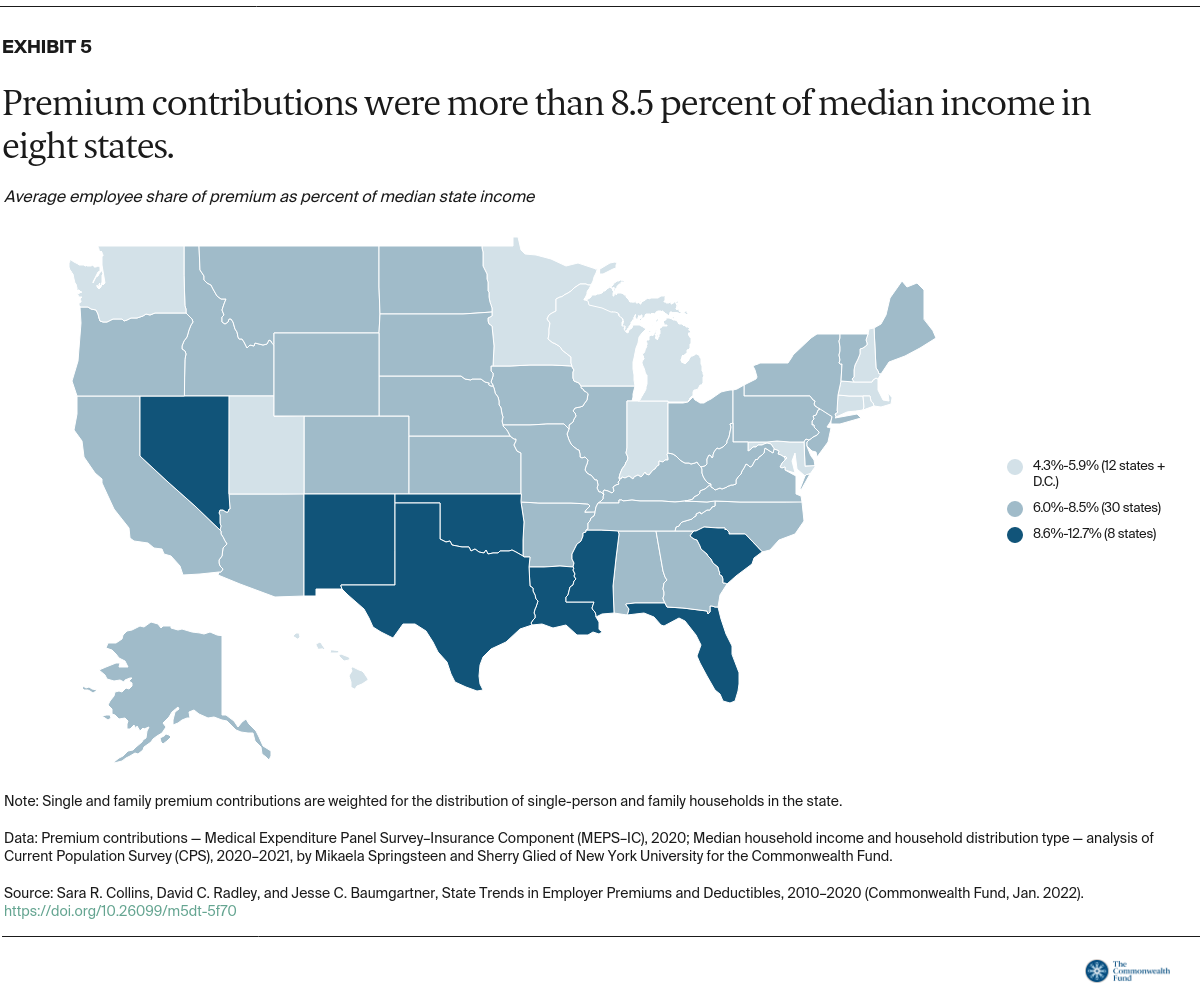

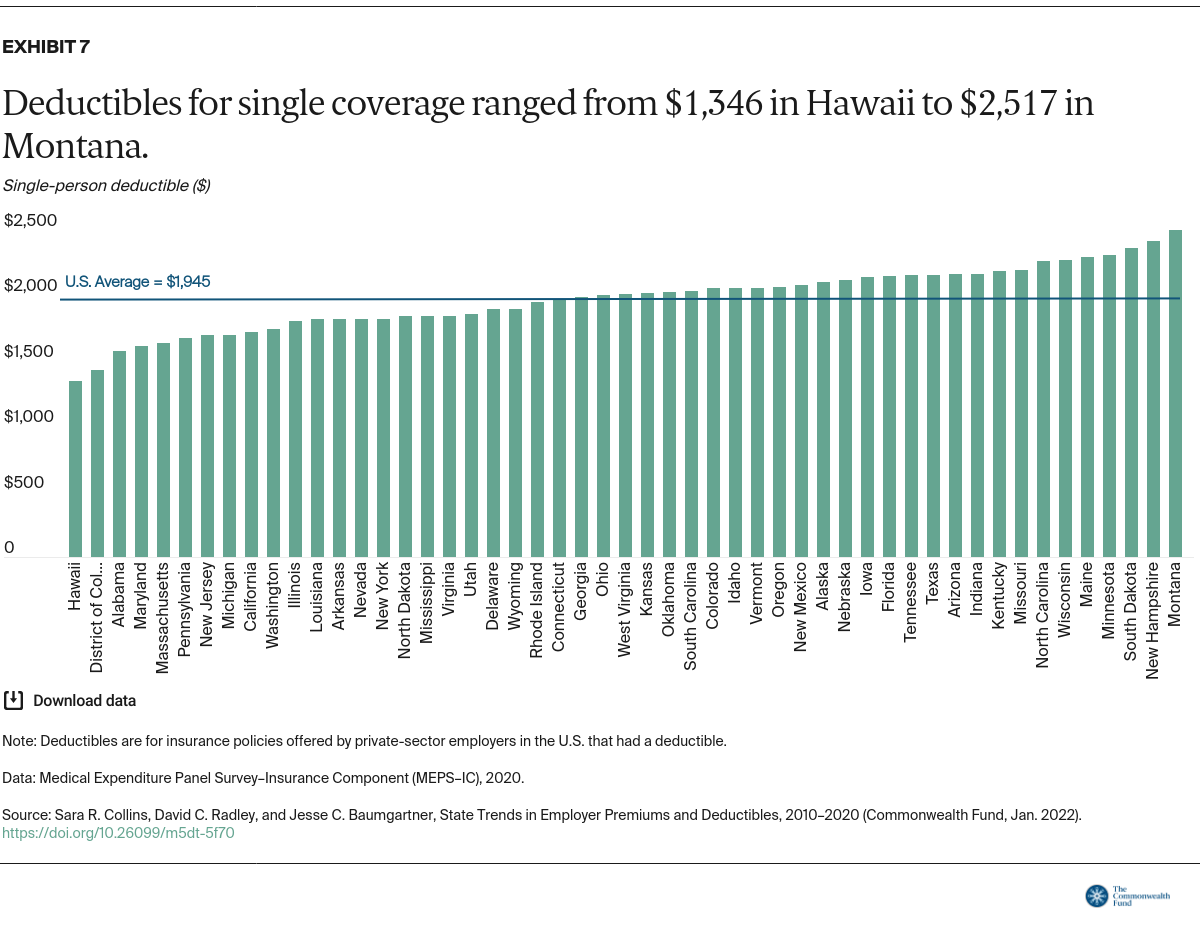

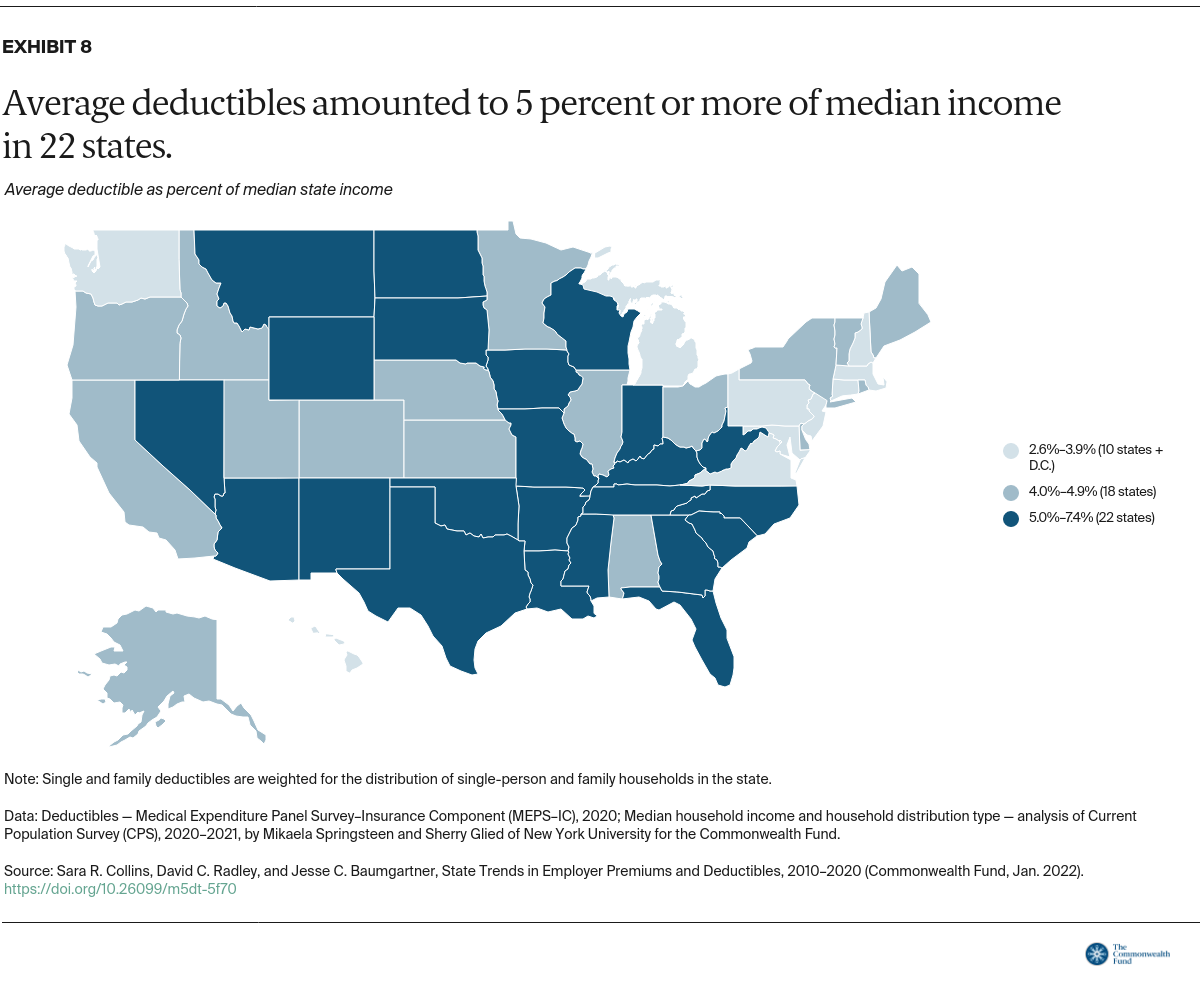

The Commonwealth Fund tracks the share of people with health coverage who are underinsured, meaning their plan does not provide adequate protection from high out-of-pocket costs and deductibles, excluding premiums.6 A deductible that accounts for 5 percent or more of household income is one of our threshold measures of being underinsured.

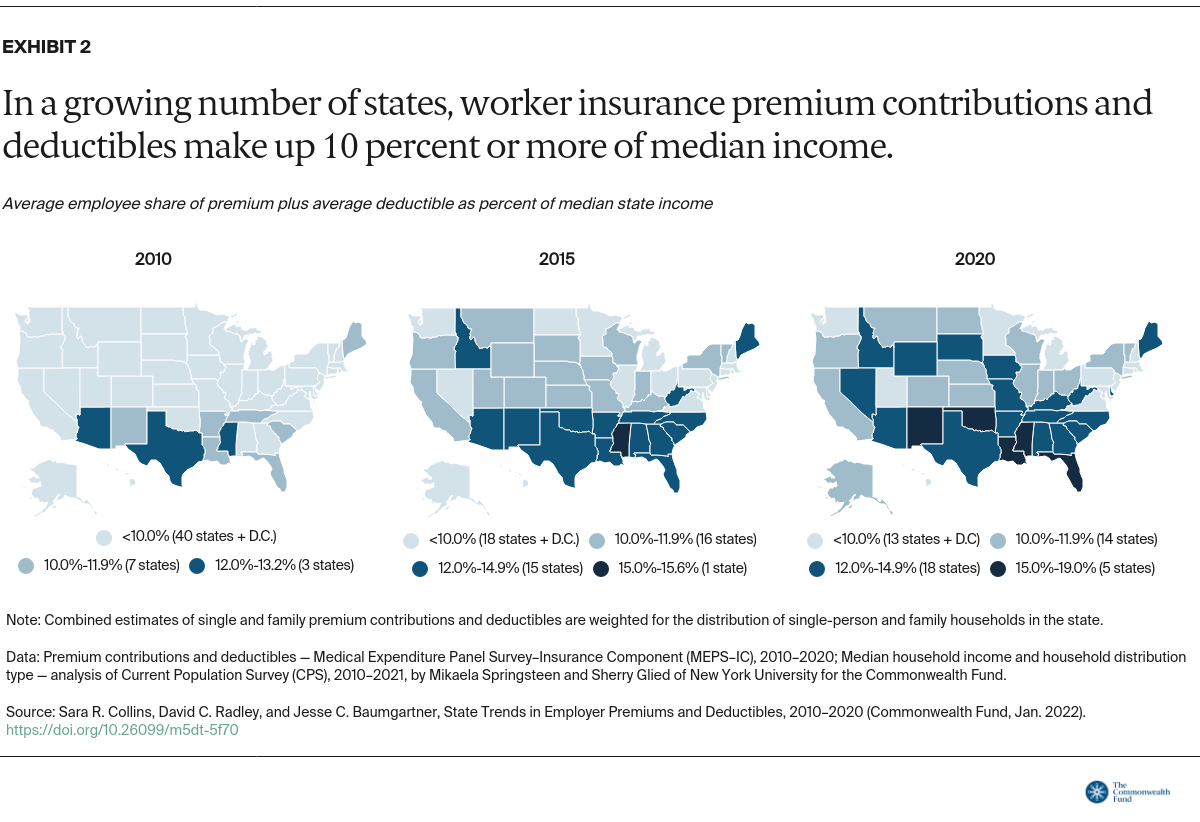

In nearly half the states, people at the midrange of the income distribution faced average deductibles that left them underinsured in 2020. In 2010, workers in just one state faced an average deductible that met that threshold.

The highest average deductible relative to median income in 2020 was 7.4 percent, in New Mexico (Table 1).

The Growing Cost of Health Insurance for America’s Middle Class

The growing cost of employer health insurance is driven by the growth in health care spending. New data from the Health Care Cost Institute show that spending per person in employer plans grew by nearly 22 percent over the period 2015 to 2019, outpacing both inflation and economic growth.7 Prices commanded by health care providers and drug companies were the primary driver, accounting for nearly two-thirds of overall spending growth.

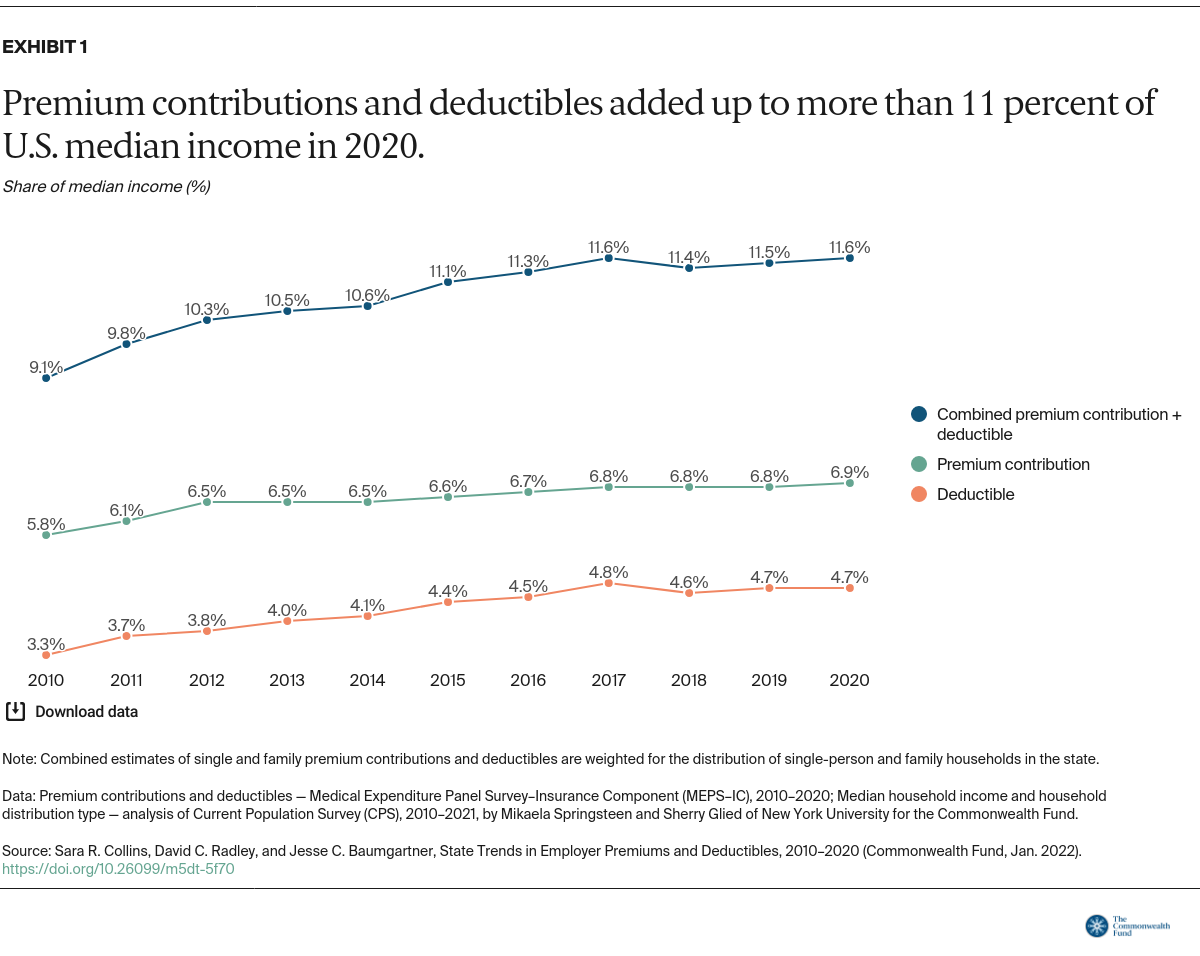

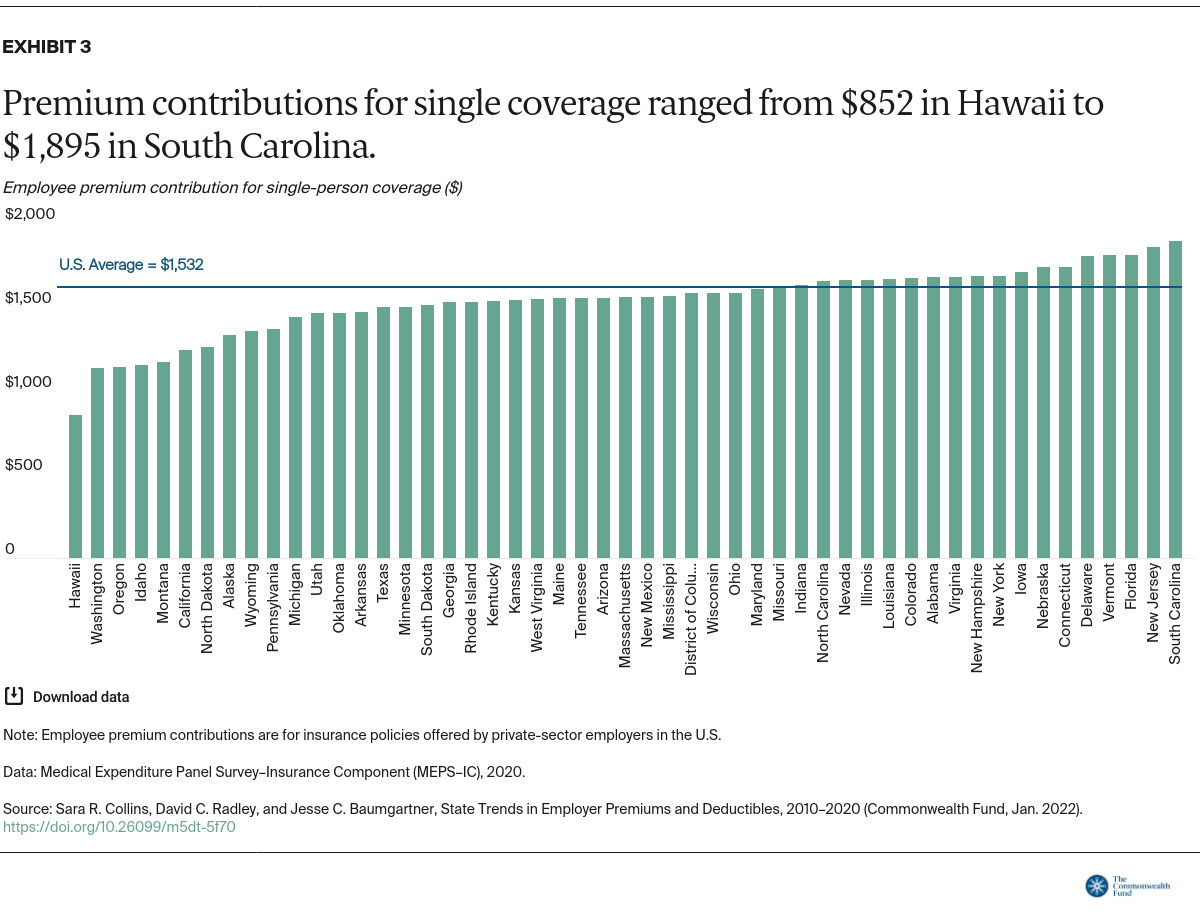

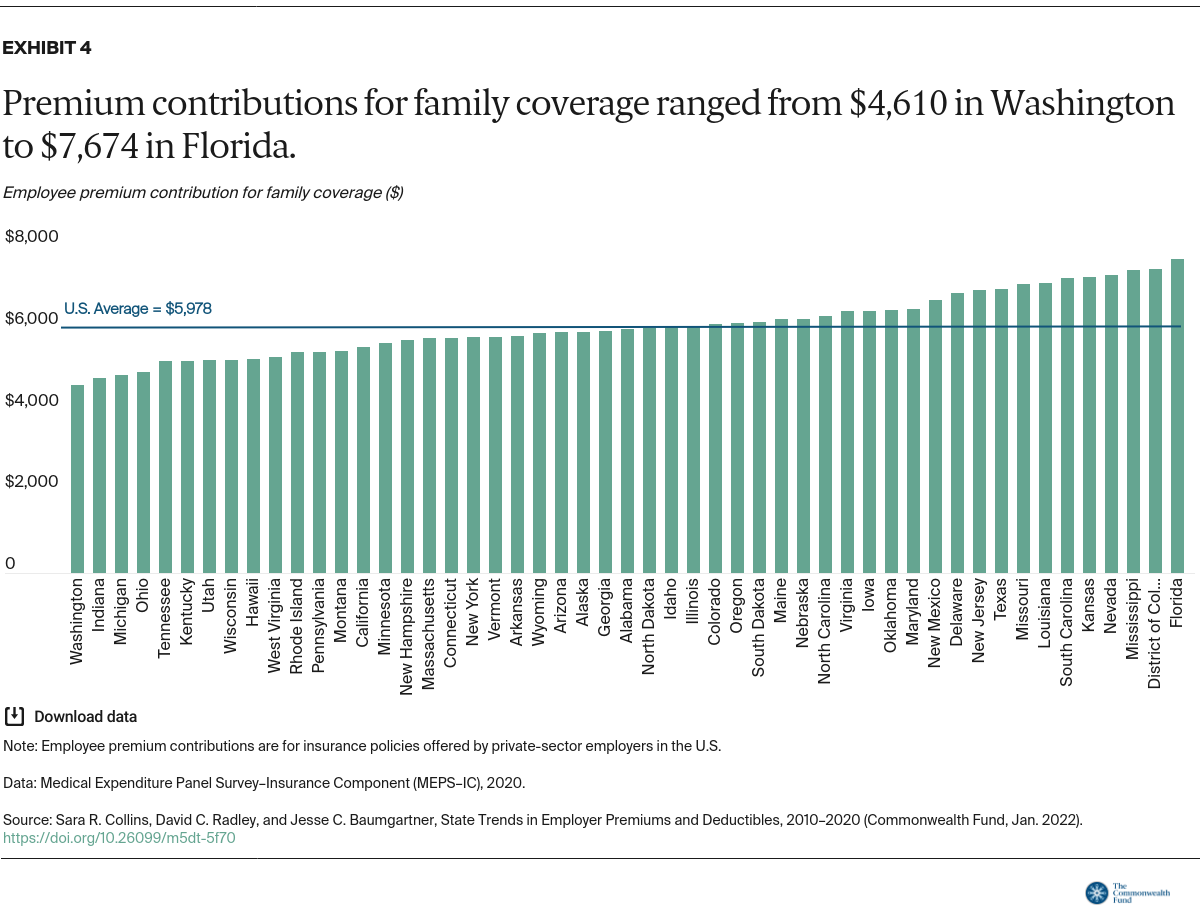

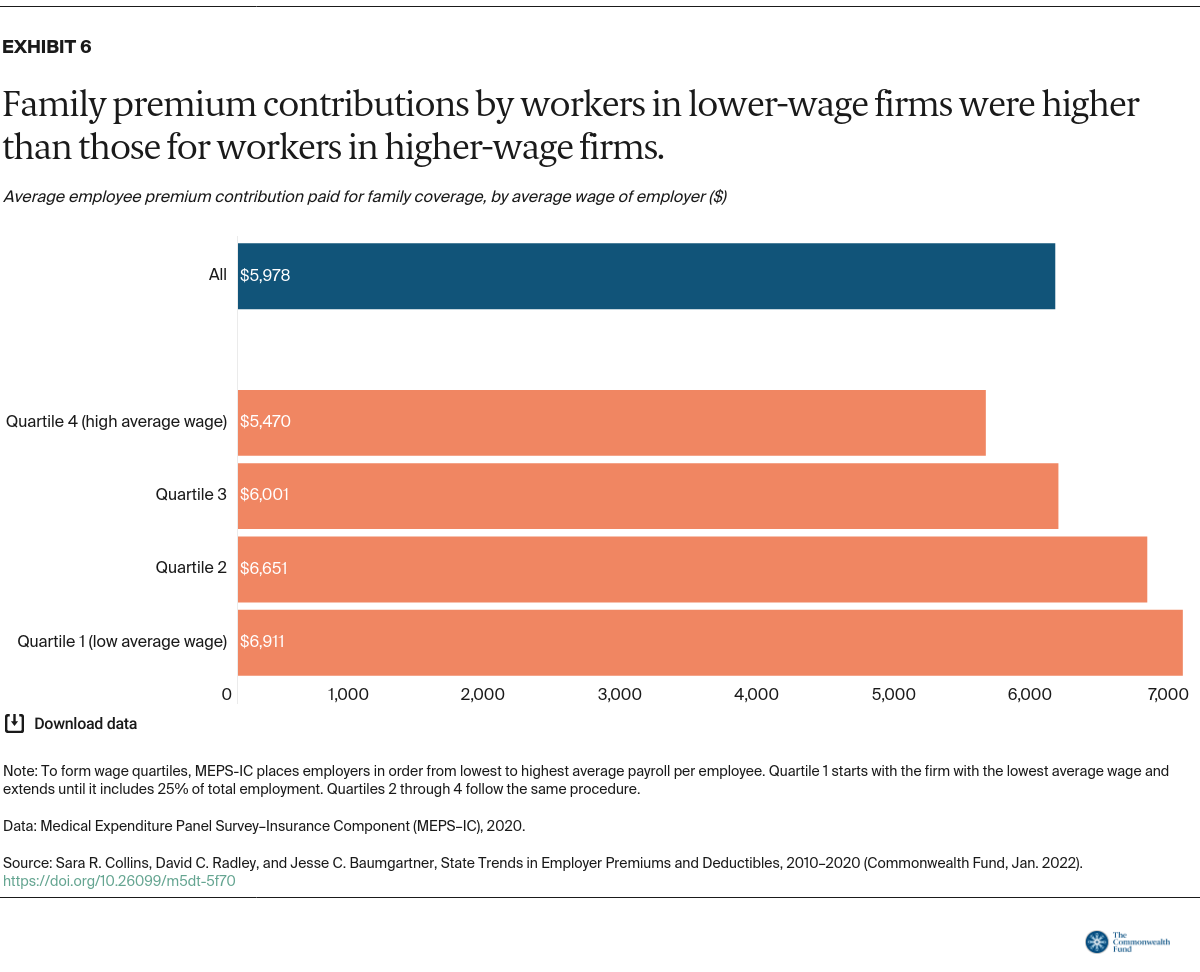

These high prices are the main reason why the amount that workers pay for their premiums and deductibles has grown over time. And because incomes have not kept pace, health insurance is taking up a larger and larger percentage of household budgets. To make matters worse, workers are making wage concessions for company benefits that often cover less of their health care costs.

These costs add to the financial burden U.S. families are already facing. Housing and food consumed 34 percent of average family income in 2020.8 Among families with children under age 5, average spending on childcare took up 13 percent of family income in 2017.9

Health care cost burdens are both an impediment to families’ ability to get timely health care and a risk to their financial security. In a 2020 Commonwealth Fund survey, more than one-third of adults in commercial insurance plans with a deductible of $1,000 or more said they had not gotten needed health care because of the cost.10 And more than 40 percent of adults with a deductible of that size reported problems paying medical bills or having to pay off medical debt.

In fact, medical bill problems and debt have become endemic in our health system. The media is awash in stories of patients receiving outlandish uncovered bills.11 A recent JAMA article found that 17.8 percent of people in the U.S. had medical debt that was turned over to a collection agency, with the highest debt burdens carried by people living in southern states and in poor zip codes.12 Between 2009 and 2020, the amount of medical debt in collections overtook that of nonmedical debt.

Medical debt has spillover financial implications as well. Among people with employer coverage who had problems paying medical bills or were paying off medical debt, 40 percent said that they had received a lower credit score because of their medical bills, 40 percent had taken on credit card debt to pay their bills, and 35 percent had used up most or all their savings to pay their bills.13

What Can Be Done?

The ACA’s marketplace plan subsidies and expansion in Medicaid eligibility have provided a critical safety net for people in high-priced or bare-bones employer health plans. The Build Back Better Act under consideration in Congress would make the most sweeping enhancements to the ACA since its passage in 2010. These include a substantial increase in marketplace premium subsidies and a new zero-premium marketplace coverage option for Medicaideligible adults who do not have access to Medicaid in their state. In addition, the bill would help more people in unaffordable employer plans gain access to marketplace subsidies. Additional efforts to expand and improve the adequacy of health insurance for U.S. workers might include:

- Addressing the high health care prices that are driving up employer premiums and deductibles, for example, by adding a public plan option to the marketplaces.14

- Allowing people to autoenroll in comprehensive health coverage. Creating a public insurance plan as a default option would be essential to a national autoenrollment program.15

- Informing workers with employer coverage about their options to enroll in subsidized marketplace plans or in Medicaid and informing workers who lose their employer coverage that they are eligible for a marketplace special enrollment period.

- Fixing the “family coverage glitch.” Under the ACA, families are ineligible for marketplace premiums if a family member’s employer offers single coverage that is deemed affordable (premiums are less than 9.83% of family income; the Build Back Better Act would lower this to 8.5 percent).16 But 5 million people eligible for family employer plans with premium contributions above that threshold are ineligible for marketplace subsidies.17 An administrative fix could save families that switched to marketplace plans an average of $400 a person annually.

- Reining in deductibles and out-of-pocket costs in marketplace plans by enhancing cost-sharing reduction subsidies and changing the benchmark plan in the ACA marketplaces from silver to gold. One proposal could eliminate deductibles for some people and reduce it for others by as much as $1,650 a year.18

- Imposing stronger consumer protection rules for medical debt collection, such as grace periods following illness or during appeals processes, and placing bans or limits on medical debt interest rates.19

The cost burden of commercial insurance in the United States is an enduring problem that is undermining Americans’ economic well-being. With the Build Back Better Act, Congress is demonstrating how it can build on the Affordable Care Act to cover the remaining uninsured and make health care affordable to all. But Congress can do more to reduce deductibles and out-of-pocket costs when people get health care. At the same time, policymakers, insurers, employers, health care providers, and drug manufacturers will need to work together to address the high health care prices that are behind much of the growing cost burden weighing on so many working families.