Abstract

- Issue: About three-quarters of nonelderly adult Medicaid patients get their primary care from independent office-based practices, rather than hospital outpatient departments or health centers. But many independent physicians don’t accept Medicaid, in part because of its low payment rates. Medicaid-covered care is concentrated in a small share of independent, typically underresourced practices, and this potentially has implications for the quality of care delivered. The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid eligibility expansion and physician fee bump, however, may have changed the distribution or care of patients across independent practices.

- Goals: Examine the distribution of Medicaid patients across office-based primary care physicians and the impact of a practice’s Medicaid patient share on care quality.

- Methods: Analysis of National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey findings for 2006–2016 and 2018–2019.

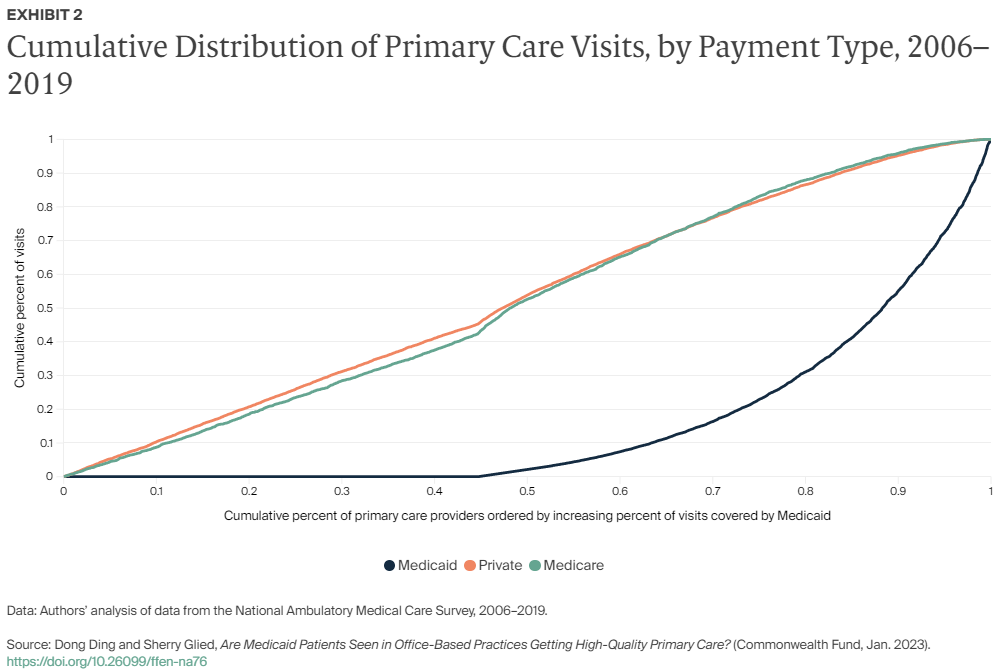

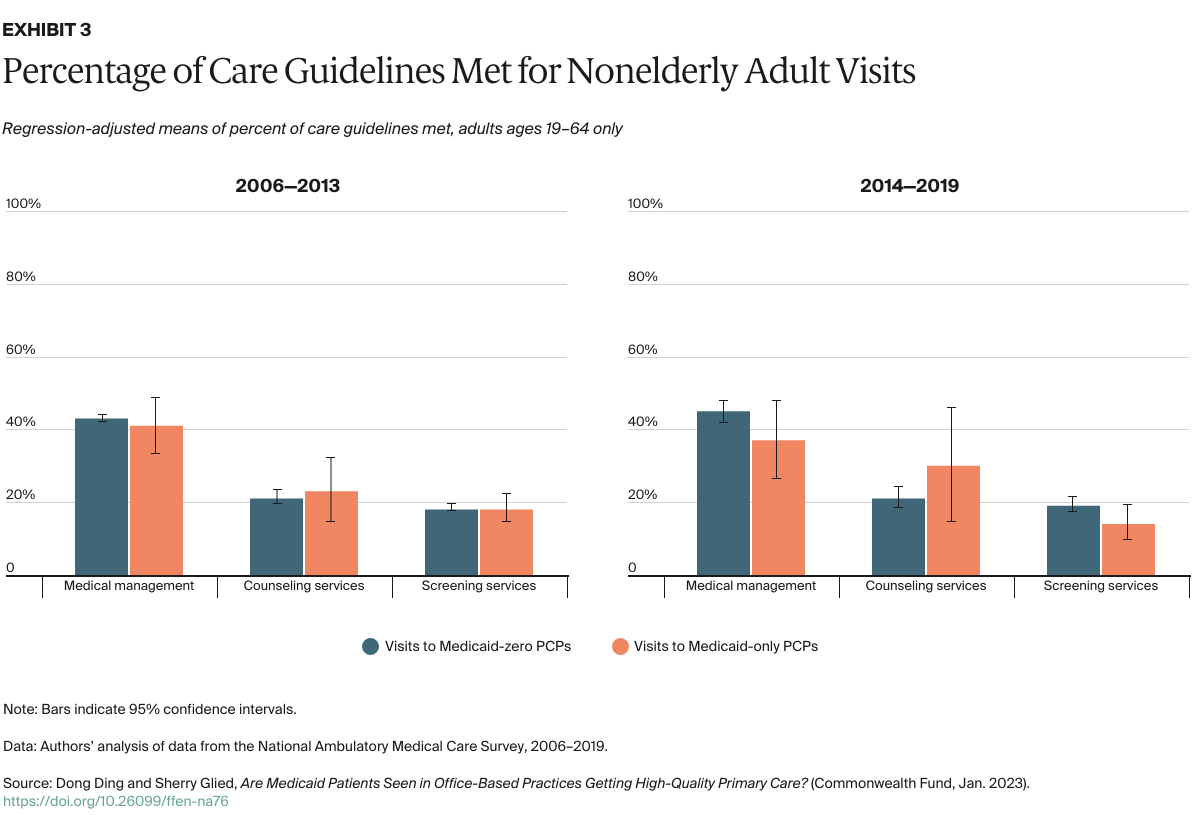

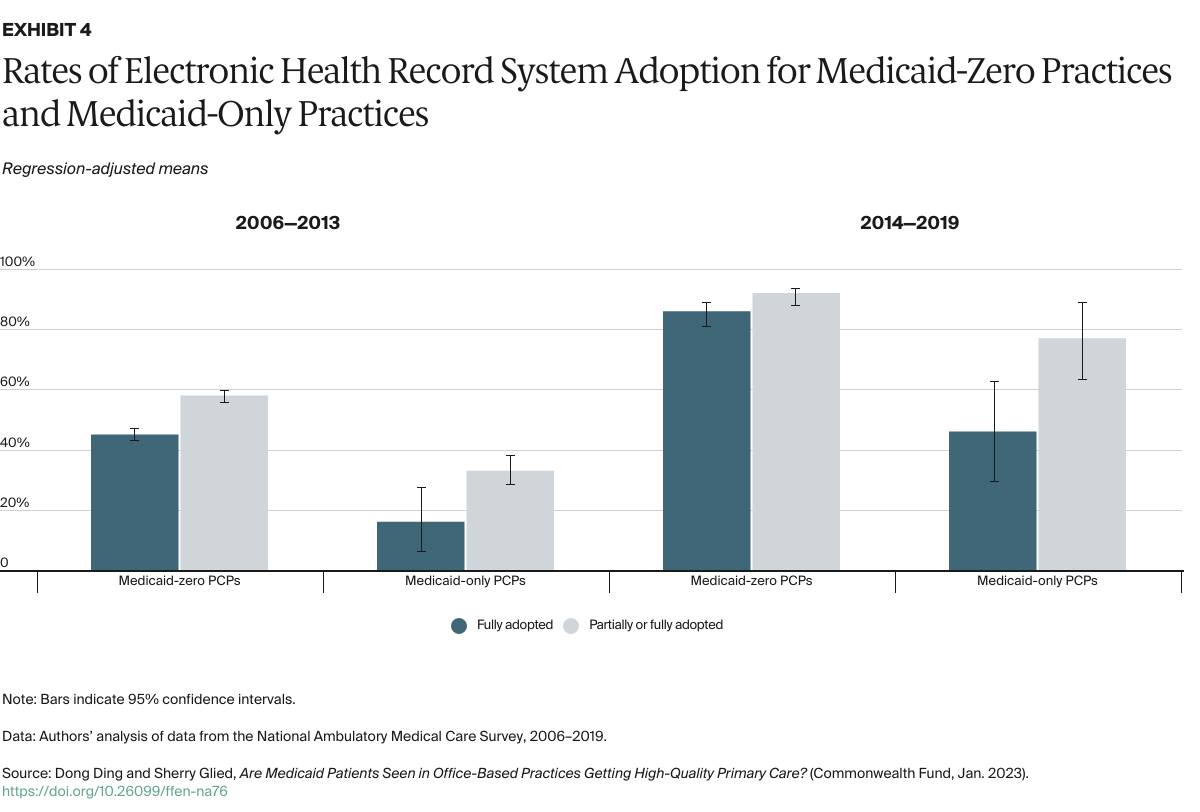

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Medicaid visits have remained concentrated in a minority of practices since Medicaid expansion. From 2014 to 2019, about one-third of sampled office-based primary care physicians accounted for 90 percent of Medicaid office visits. Patients are as likely to receive guideline-recommended care at Medicaid-dominated practices as they are at practices with more non-Medicaid patients, but the former are much less likely than the latter to have adopted electronic health records. This suggests that low payment rates may affect practices’ ability to invest in technology that promotes high-quality care.

Introduction

Independent office-based physician practices play an important role in providing primary care for Medicaid patients. In 2011, Medicaid patients between 19 and 64 years of age made 47 million visits to either an office-based or hospital outpatient primary care provider (PCP). Of these visits, about 75 percent took place at an independent office-based practice (Appendix 1). This percentage is somewhat greater than estimates from the late 1990s.1 Medicaid’s low payment rates for office-based visits have long led to concerns about the concentration of Medicaid patients in these practices, particularly regarding the quality of care they provide.2

In 2014, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) extended Medicaid eligibility to adults younger than age 65 with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. As a result, some 11 million individuals who had previously been uninsured gained Medicaid coverage by the end of that year.3 But while coverage expanded, questions remained about whether newly insured Medicaid beneficiaries would be able to access the care they need. That’s because Medicaid physician payment rates have historically been well below those of Medicare or private insurance rates.4 This fee discrepancy has contributed to many physicians’ reluctance to accept new Medicaid patients, which has left them clustered in a subset of practices.5

Partially in response to the concern over access, the ACA included a Medicaid fee bump that raised payment rates for Medicaid primary care visits to Medicare levels in 2013 and 2014. In 17 states, these higher fees continued past 2014. However, research suggests that the fee bump had only modest effects on access to care and physician participation in Medicaid.6

Research conducted since the passage of the ACA has confirmed that newly insured Medicaid patients have indeed been able to access care.7 On the supply side, surveys have shown that although the proportion of primary care physicians willing to accept new Medicaid patients remained lower than the share of physicians willing to accept new Medicare or private patients, it increased from 67 percent in the 2011–2012 period to 75 percent in the 2014–2017 period.8 While these results are reassuring, it is not clear whether this increased willingness to accept new Medicaid patients has changed the distribution of these patients among physician practices.

The distribution of patients among practices is a concern because Medicaid’s lower payment rates disadvantage those practices that participate in the program. Lower payment rates might lead practices to reduce the resources they devote to individual visits (for example, by seeing patients for very brief visits or providing poor-quality care) or diminish their ability to invest in fixed assets such as electronic health records (EHRs).9 As most evidence suggests that physician practice patterns do not vary by individual patients’ insurance status,10 any effect of lower Medicaid payment rates on quality is likely to be a function of the proportion of a practice’s patients who are covered by Medicaid, rather than by the insurance status of individual patients.

For this brief, we analyzed 2006–2019 office-based visit data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey to examine 1) recent changes in the distribution of Medicaid visits across primary care providers over time and 2) the relationship between the insurance composition of a PCP and measures of quality of care and technology adoption (for more details, see “How We Conducted This Study”). While previous studies have examined the relationship between hospital payer distribution and quality of care, there has been little prior analysis of this dimension of primary care.

Key Findings

Distribution of Medicaid Visits Across Physician Practices

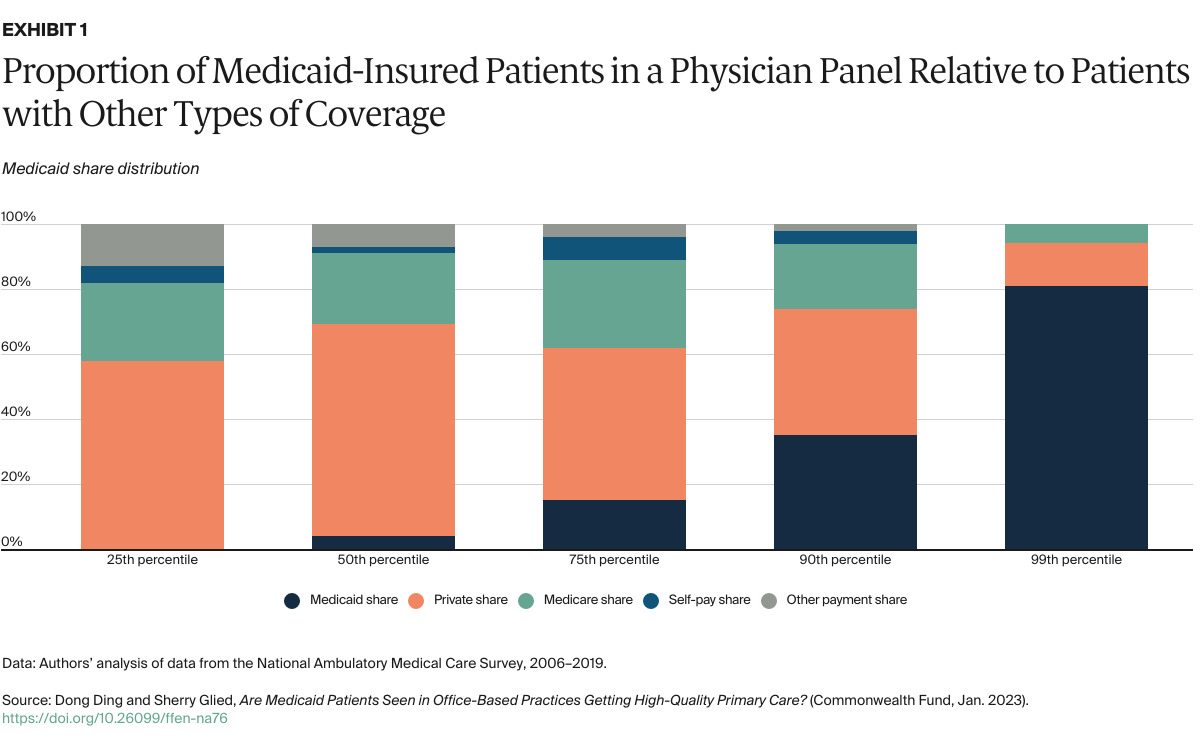

We examined the payment-type composition of a physician practice at different percentile points along the Medicaid share distribution (Exhibit 1). For example, in a practice at the median of the Medicaid share distribution, 4 percent of patients in a practice panel are covered by Medicaid, 66 percent by private insurance, and 22 percent by Medicare. At the 99th percentile of the Medicaid share distribution, 81 percent of patients in a practice are covered by Medicaid, 13 percent by private insurance, and 6 percent by Medicare. Between the periods 2006–2013 and 2014–2019, the Medicaid share within practices increased, while the share of visits that were uninsured (self-pay or other) declined.