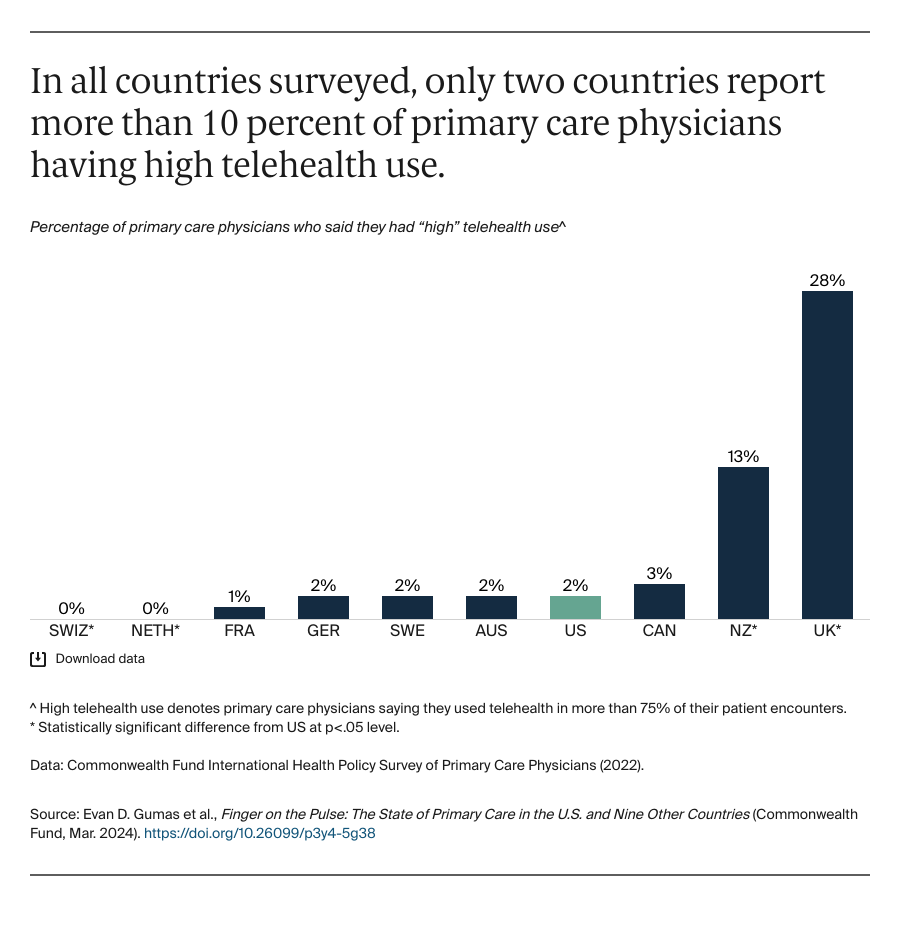

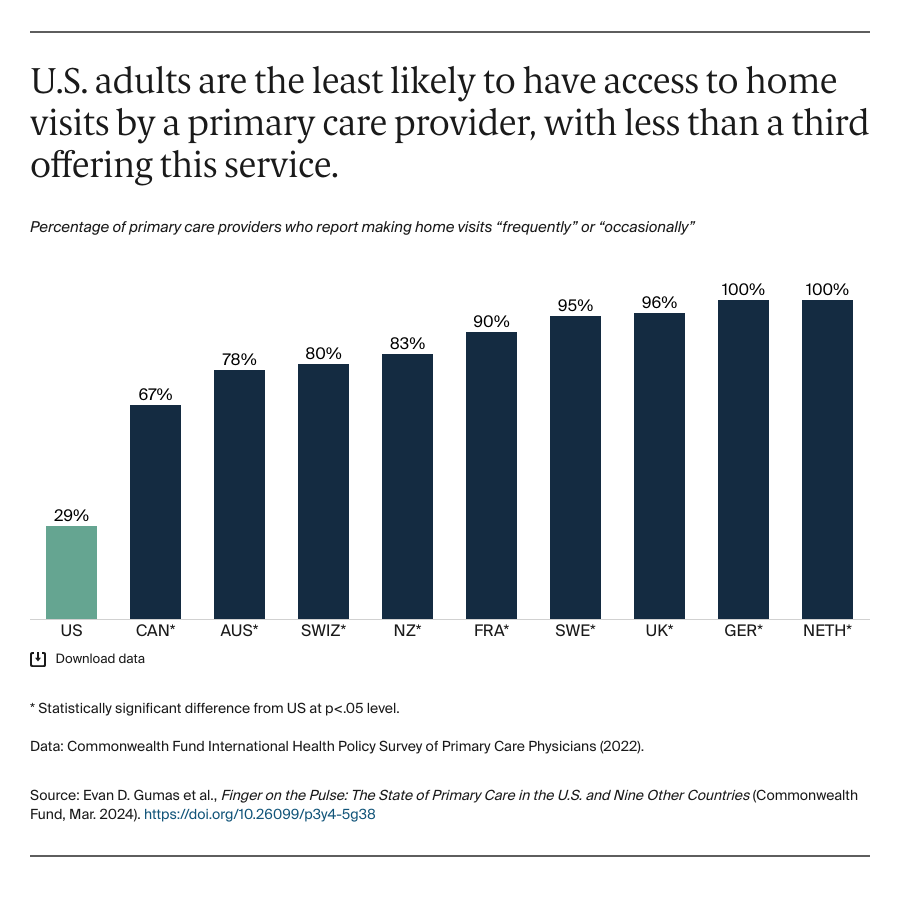

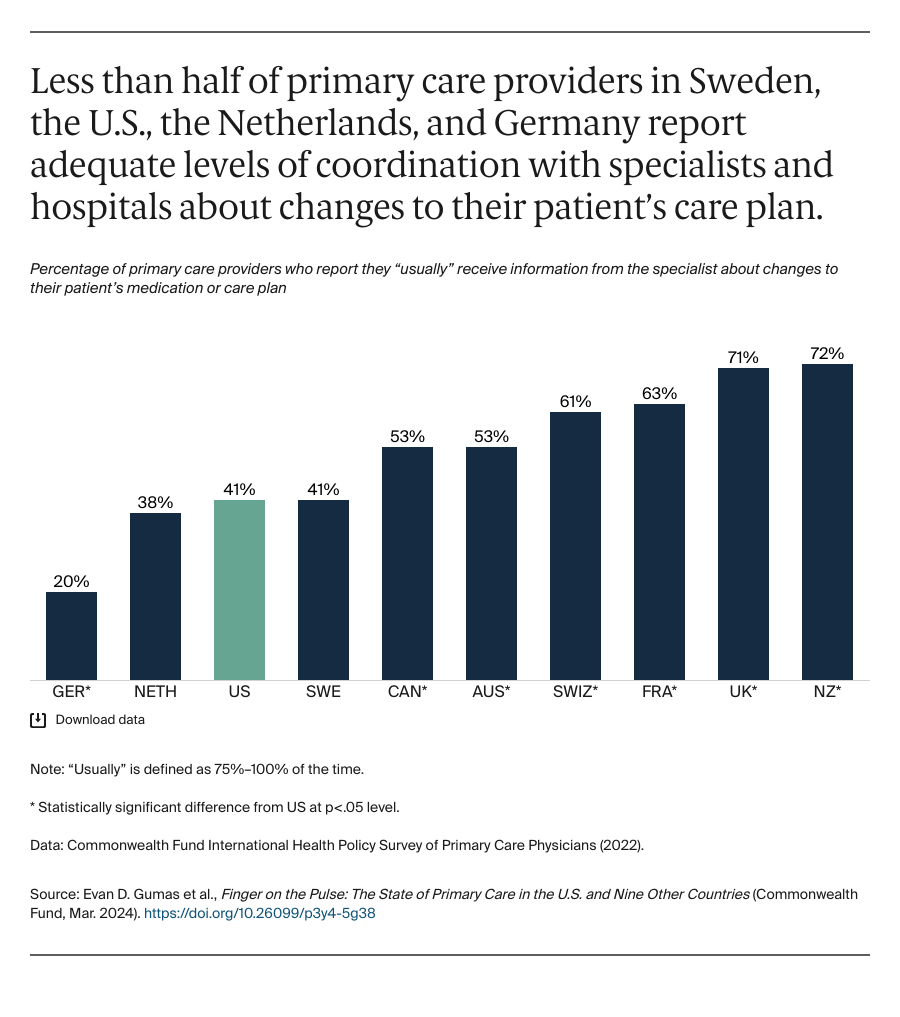

The Commonwealth Fund 2022 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians was administered to nationally representative samples of practicing primary care doctors in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These samples were drawn at random from government and private lists of primary care doctors in every country except France, where they were selected from publicly available lists of primary care physicians. Within each country, experts defined the physician specialties responsible for primary care, recognizing that roles, training, and scopes of practice vary across countries. In all countries, general practitioners (GPs) and family physicians were included, with internists and pediatricians also sampled in Switzerland and the United States.

The questionnaire was designed with input from country experts and pretested in most countries. Pretest respondents provided feedback about question interpretation via semistructured cognitive interviews. SSRS, a survey research firm, worked with contractors in each country to survey doctors from February through September 2022; the field period ranged from 8 to 31 weeks. Survey modes (mail, online, and telephone) were tailored based on each country’s best practices for reaching physicians and maximizing response rates. Sample sizes ranged from 321 to 2,092, and response rates ranged from 6 percent to 40 percent. For analyses that are limited to primary care physicians who use telehealth, sample sizes ranged from 317 to 2,056. Across all countries, response rates were lower than in 2019. Final data were weighted to align with country benchmarks along key geographic and demographic dimensions.

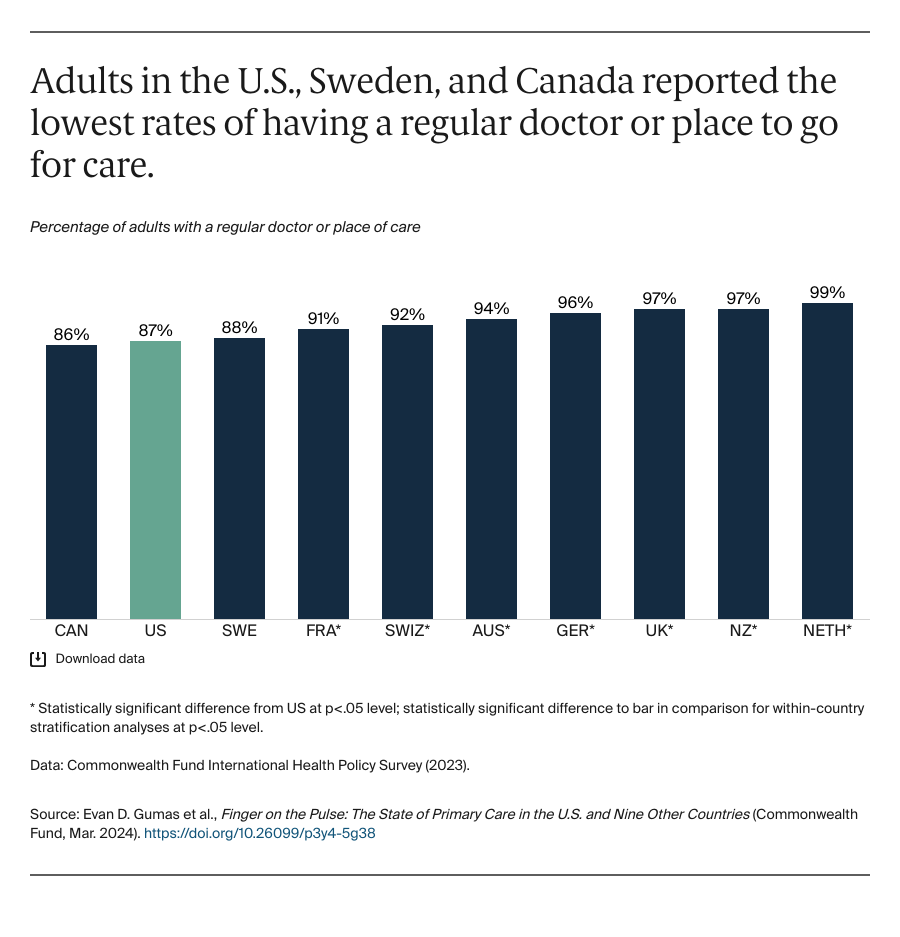

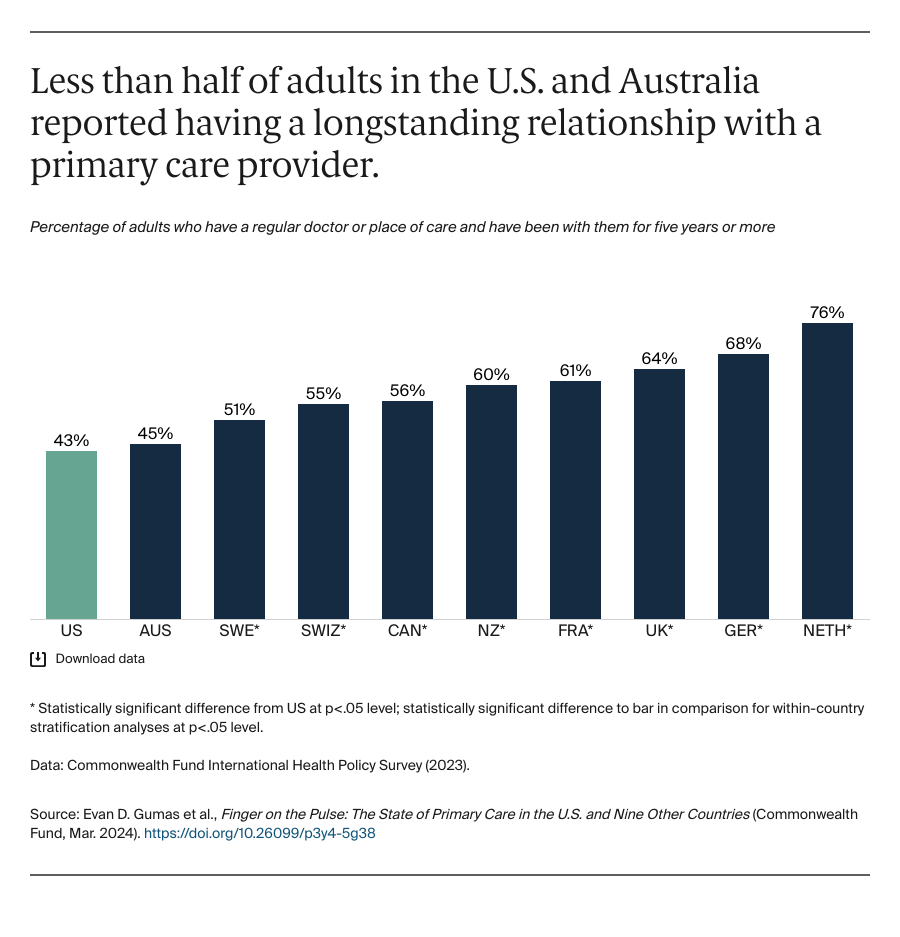

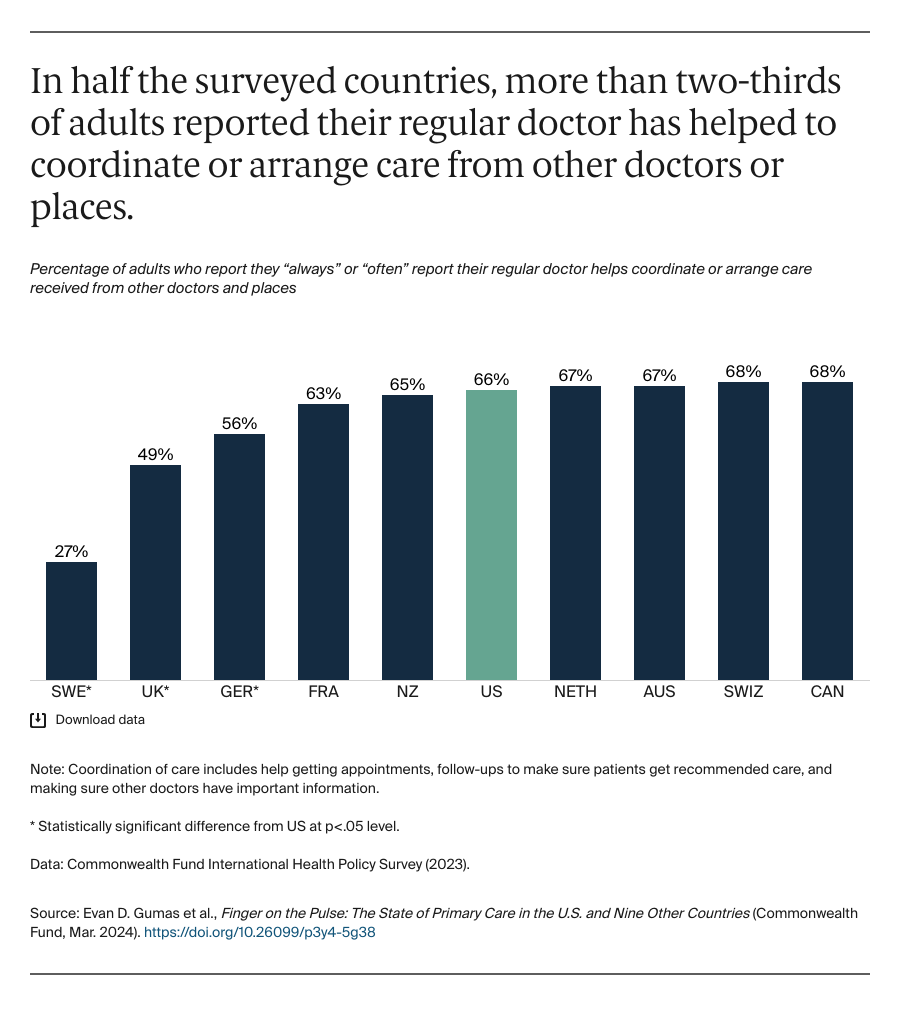

The Commonwealth Fund 2023 International Health Policy Survey collected data from nationally representative samples of noninstitutionalized adults age 18 and older in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Samples were generated using probability-based overlapping landline and mobile phone sampling designs in Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the U.K. In the U.K., additional online interviews were completed via a nationally representative probabilistic panel. In Sweden and Switzerland, respondents were randomly selected from listed or nationwide population registries, and surveys were completed via landline and mobile phones, as well as online. In the U.S., three probability-based sample frames were used. Most of the interviews were conducted from address-based sample (ABS). Additional interviews were completed via a nationally representative probabilistic panel and from a sample of cell phone numbers connected to prepaid cell phones to reach populations who are typically underrepresented in ABS samples, including low-income and non-white adults. Respondents in the U.S. completed surveys via mobile phones as well as online.

International partners cosponsored surveys, and some supported expanded samples to enable within-country analyses. Final country samples ranged from 750 to 4,820 participants. The survey research firm SSRS was contracted to field the survey in the U.S. and six additional countries, as well as collaborate with fieldwork partners and oversee survey administration in the other three countries, from March to August 2023, though the field period for each country varied. SSRS also provided methodological oversight for the study as a whole, including supporting questionnaire development, consultation and design of sampling protocols, and managing the statistical weighting across countries. Response rates varied from 6 percent to 49 percent. Data were weighted using country-specific demographic variables to account for differences in sample design and probability of selection.

Changes to Included Exhibits

There were some notable changes between the 2022 and 2023 International Health Policy Surveys — some questions were no longer asked, wording was changed, or new questions were added. In this edition, we did not report if patients with a regular doctor received information on how to get help meeting their social needs; the percentage of primary care providers who have social workers in their practice; or the percentage of primary care physicians who had mental health providers in their practice. This edition includes new measures on access to telehealth, preparedness to treat behavioral health conditions, and care coordination.