Others were interested in using competitive bidding among plans to bring down payment rates, saying CMS has sufficient information to set benchmarks using plan-submitted information rather than basing them on projected FFS spending. To address concerns that some counties don’t have enough plans to make competitive bidding a viable option, one suggested expanding the geographic regions to include multiple counties or even an entire state.

Even if the existing benchmarking system is retained, many thought counties were too small a unit of measure to set benchmarks. One thought that bundling counties together and requiring plans to serve an entire region might increase competition.

How Should Extra Benefits Be Paid For?

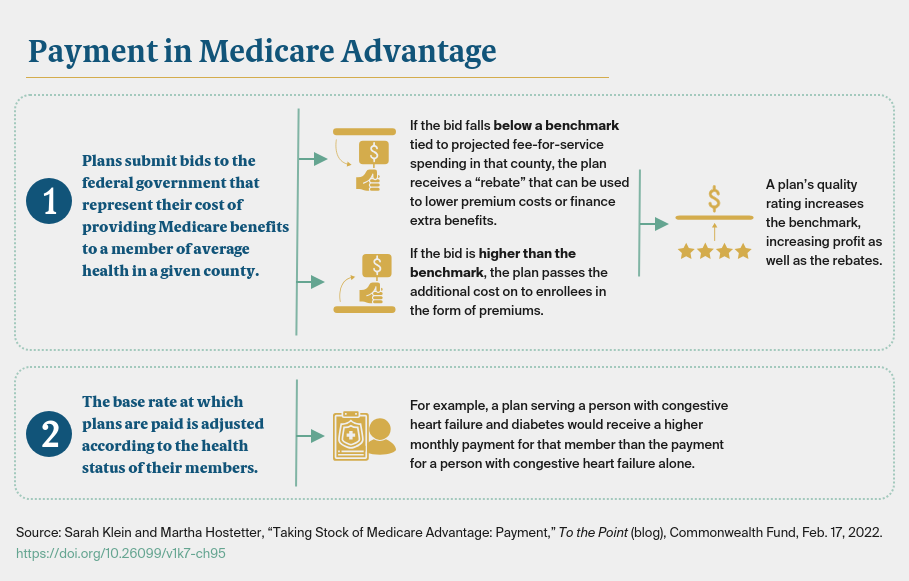

We also asked about financing supplemental benefits through rebates. CMS returns to plans a portion of the difference between their bids and the county-level benchmarks (between 50% and 70%, depending on plans’ quality scores) so they can finance supplemental benefits, lower cost sharing, or reduce premiums. The approach favors counties where traditional Medicare spending is high, such as Miami’s Dade County. Medicare Advantage beneficiaries there receive more supplemental benefits than those in areas of the country where health care spending is lower, like Iowa or Minnesota.

There was no shortage of ideas for reforming this system. One option is to convert rebates to a cash equivalent and give beneficiaries the option of how to use them — from paying down premiums to purchasing personalized supplemental benefits. Another option is to place a financial cap on the actuarial value of supplemental benefits and/or standardize the menu of supplemental benefits available. At minimum, many wanted to see greater transparency around rebate dollars to understand how they are applied and the value of the benefits they are used to purchase. One concern is whether plans are purchasing benefits from entities owned by their plan’s parent company at inflated prices to increase profits.

Disentangling Payment from the Fee-for-Service Program?

Another fundamental question is whether Medicare Advantage benchmarks should be tied to FFS spending at all. This question becomes more pressing as Medicare Advantage enrollment increases and begins to overtake FFS enrollment. This has already happened in some counties, raising the question of whether the remaining FFS beneficiaries are a representative population on which to base Medicare Advantage payments. If the minority of beneficiaries who remain in the FFS program are older and sicker than most of those in Medicare Advantage, the benchmarks used to determine payment would be inflated, creating excess payments.

Some of the experts we interviewed suggest if we continue to use FFS spending as the benchmarks, we should make sure they aren’t inflated by inefficiencies in the FFS program, including greater use of skilled nursing facilities or institutional care in some regions of the country. Benchmarks also could be adjusted downward to account for the effects of Medigap policies, the supplemental insurance that many people buy to defray the cost of coinsurance in the FFS program. By shielding traditional Medicare beneficiaries from out-of-pocket costs and making them more likely to use medical services, Medigap policies drive up FFS spending and thereby increase benchmarks (and potential profits) to Medicare Advantage plans, as well as extra benefits for those they cover. Another option is to eliminate the benchmarks and have plans compete against one another, as described above.

Moving Forward

With more people opting into Medicare Advantage plans, it’s important to use taxpayer dollars responsibly in funding the program. In deciding whether and how to adjust Medicare payment to private plans, policymakers must first be clear-eyed about the goals of the program and then take steps to achieve program — and plan — efficiencies while preserving access and quality of care for beneficiaries.