Abstract

- Issue: Since 2019, Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have had the flexibility to address enrollees’ unmet needs by targeting benefits to beneficiaries with chronic illnesses and offering a wider array of “primarily health-related” benefits. As of 2020, plans can also offer Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI) — nonmedical services such as pest control.

- Goals: To assess the availability of and enrollment in MA plans offering new types of supplemental benefits in 2019 and 2020.

- Methods: Analysis of 2018–2020 Plan Benefit Package and MA enrollment data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

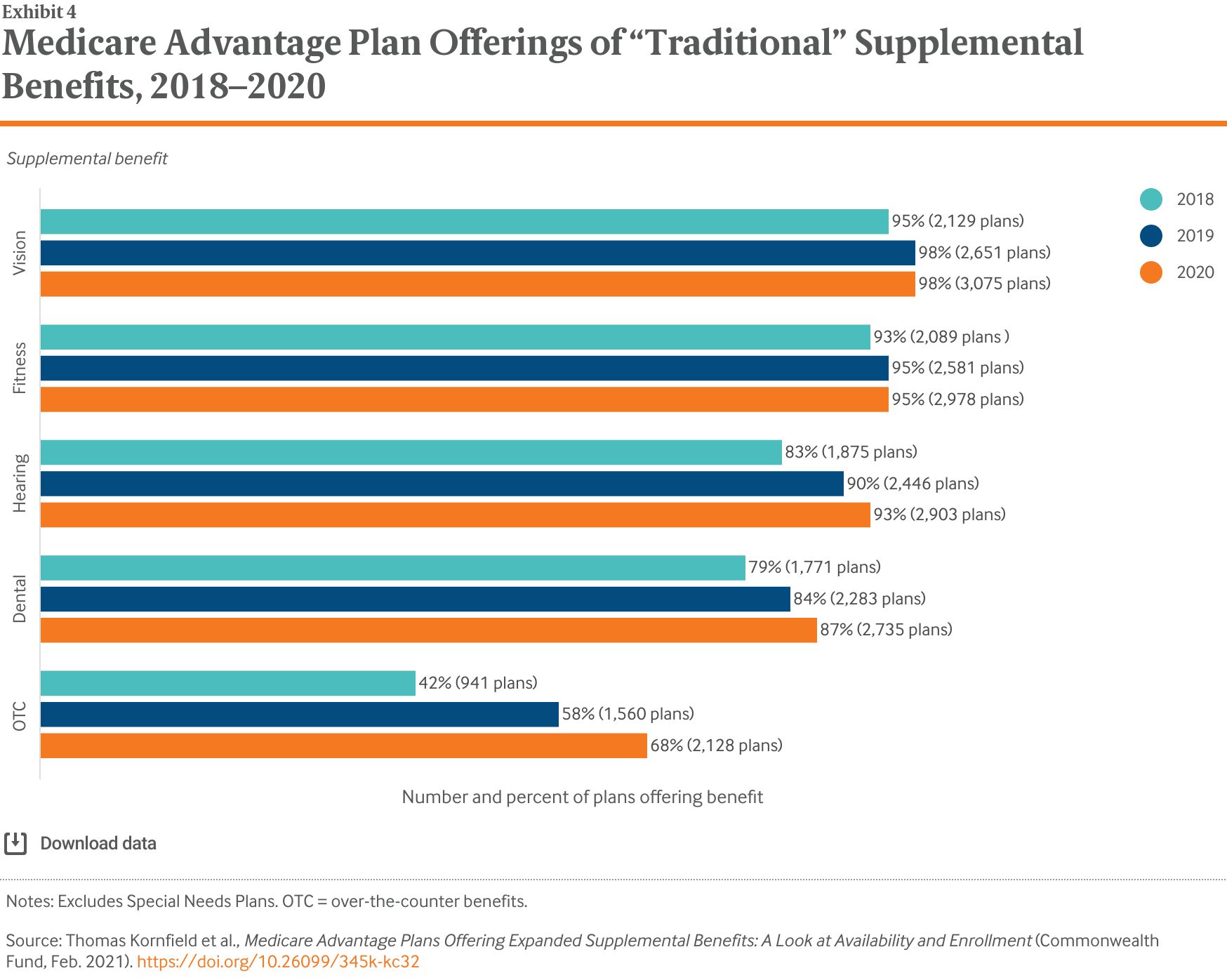

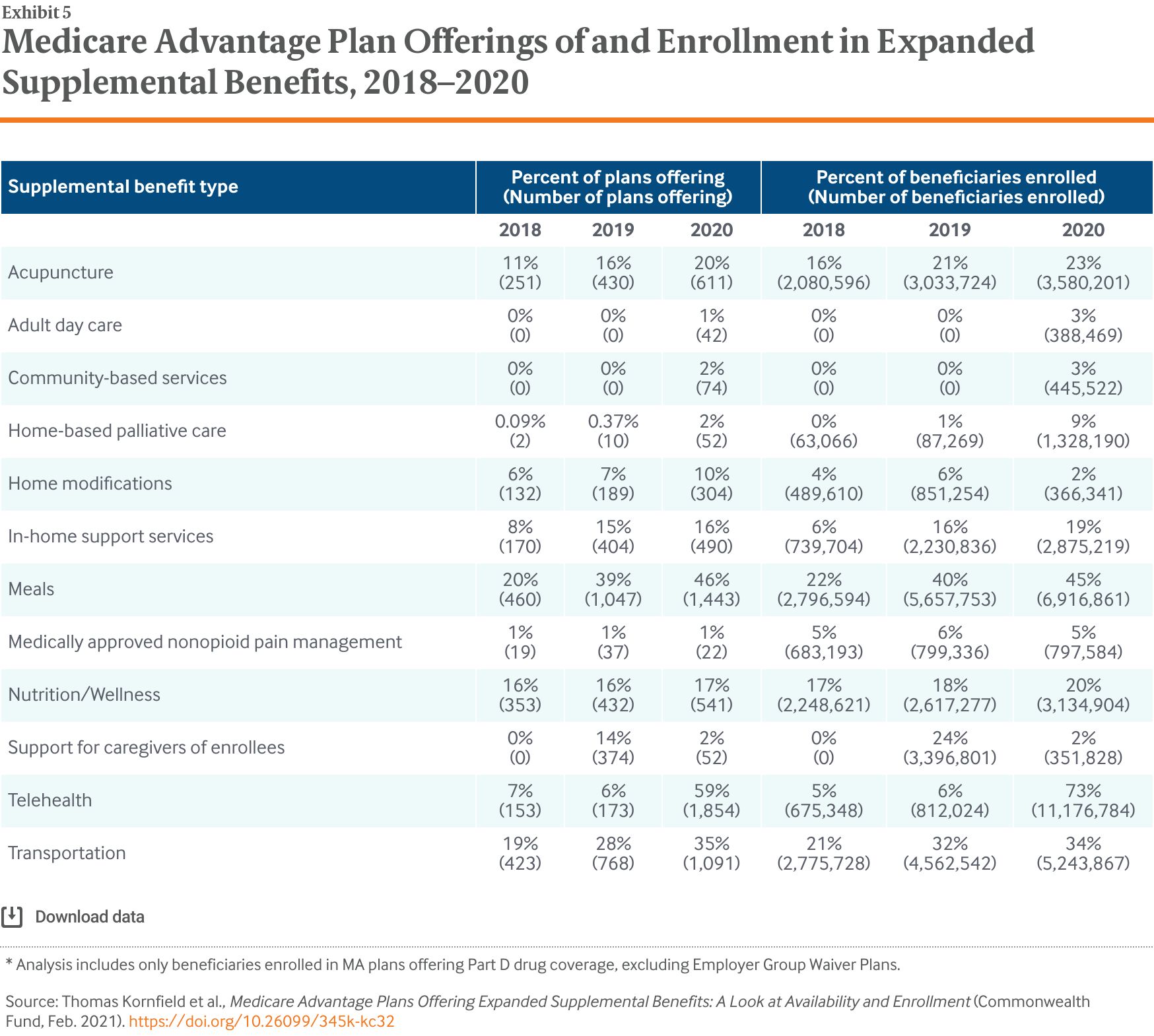

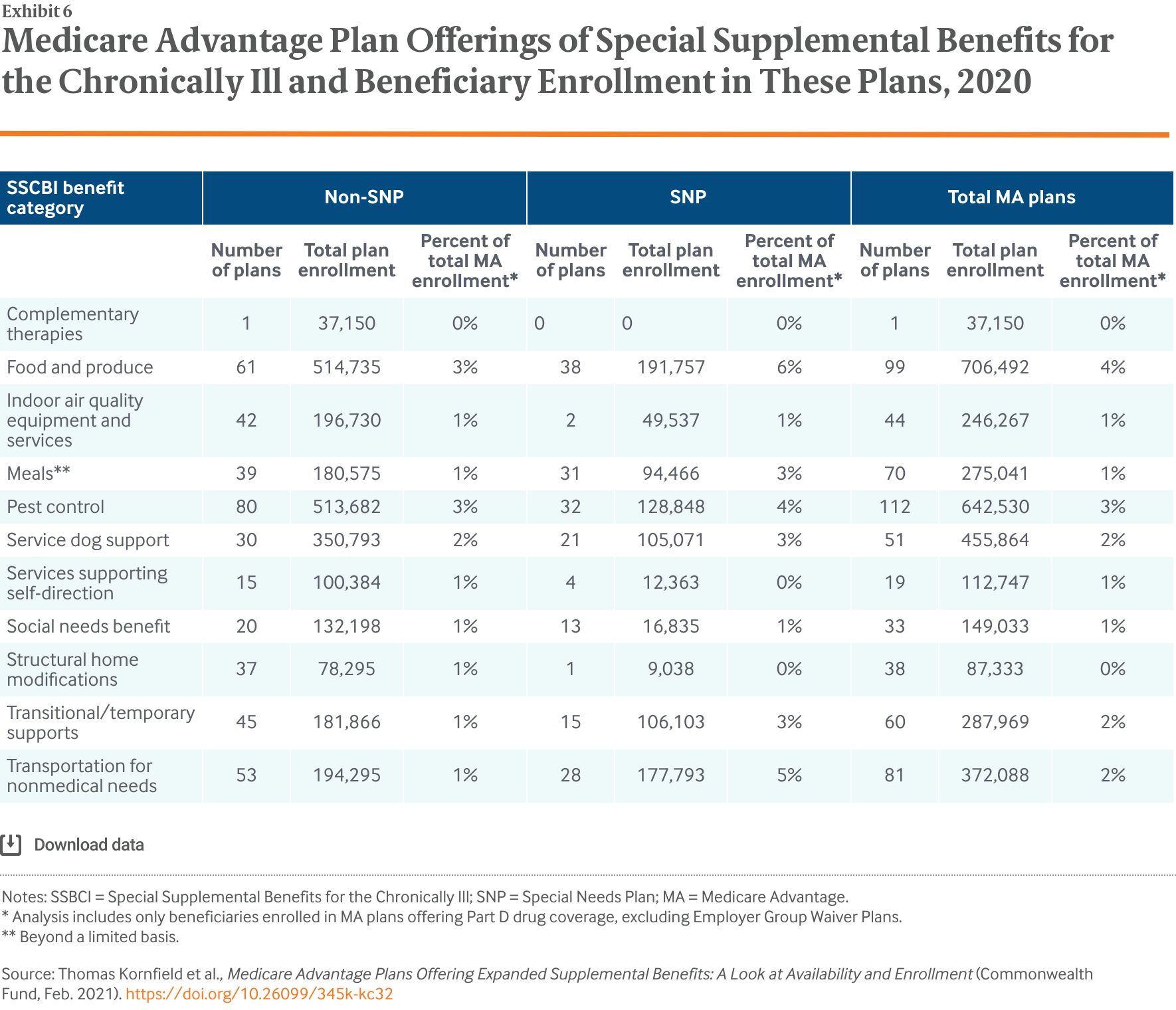

- Key Findings: Adoption of SSBCI was relatively limited in the first year: only 6 percent of MA plans offered these benefits in 2020. However, plans offering additional, primarily health-related supplemental benefits increased substantially between 2018 and 2020, including meal provision (20% of plans to 46% of plans), transportation (19% to 35%), in-home support services (8% to 16%), and acupuncture (11% to 20%).

- Conclusion: The relatively small percentage of plans offering SSBCI in 2020 may be due in part to operational and logistic challenges. But based on initial insight into 2021 plan benefit offerings, the trend toward more benefits that address social determinants of health will continue.

Introduction

Research shows that when medical care is delivered alongside nonmedical services that affect health, patients, caregivers, and the health care system overall are better off.1 Social services not traditionally considered medical services, such as transportation and nutrition, are particularly crucial for meeting the needs of high-need, high-cost Medicare beneficiaries; in addition to improving health outcomes, they may also lower costs.2

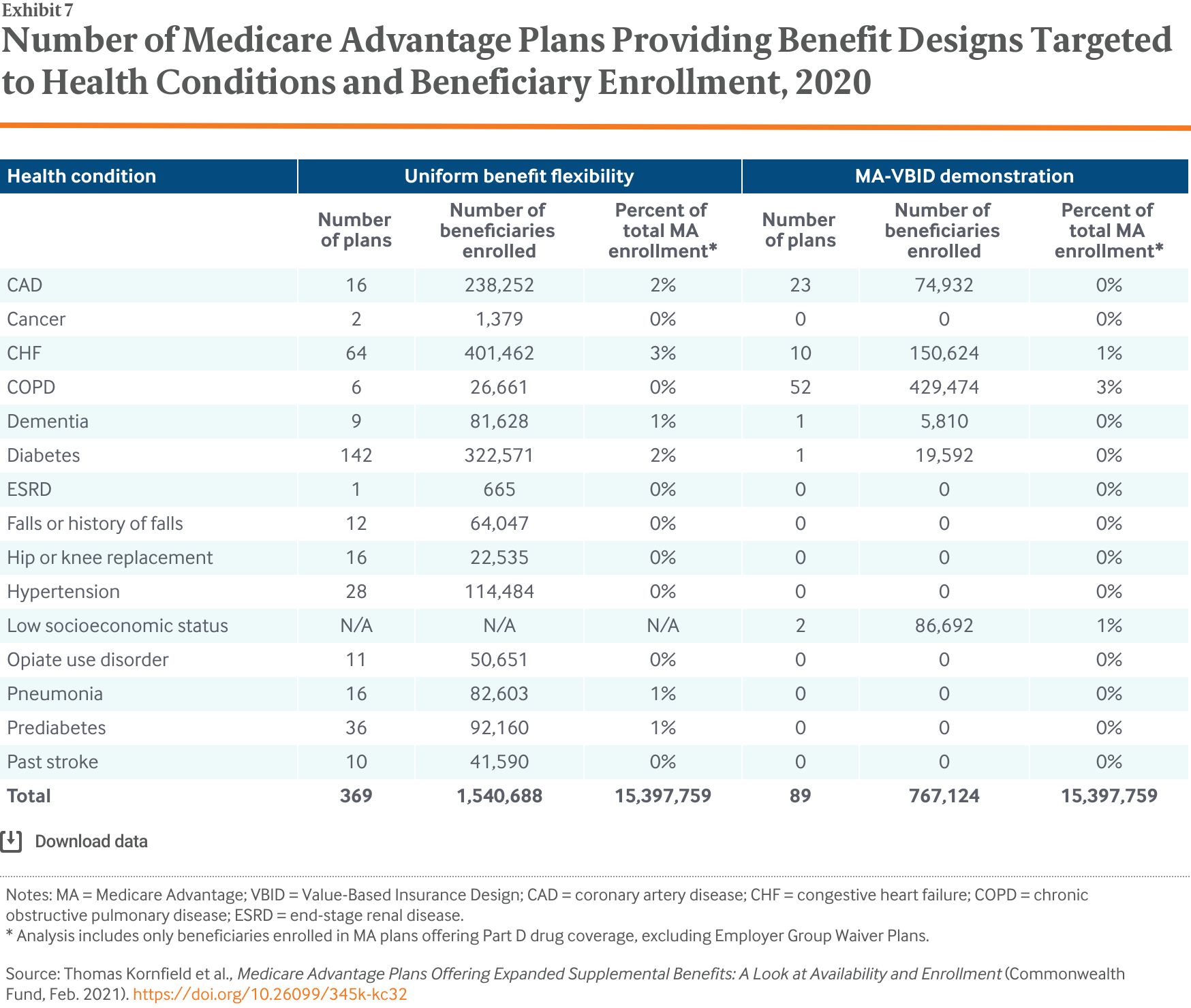

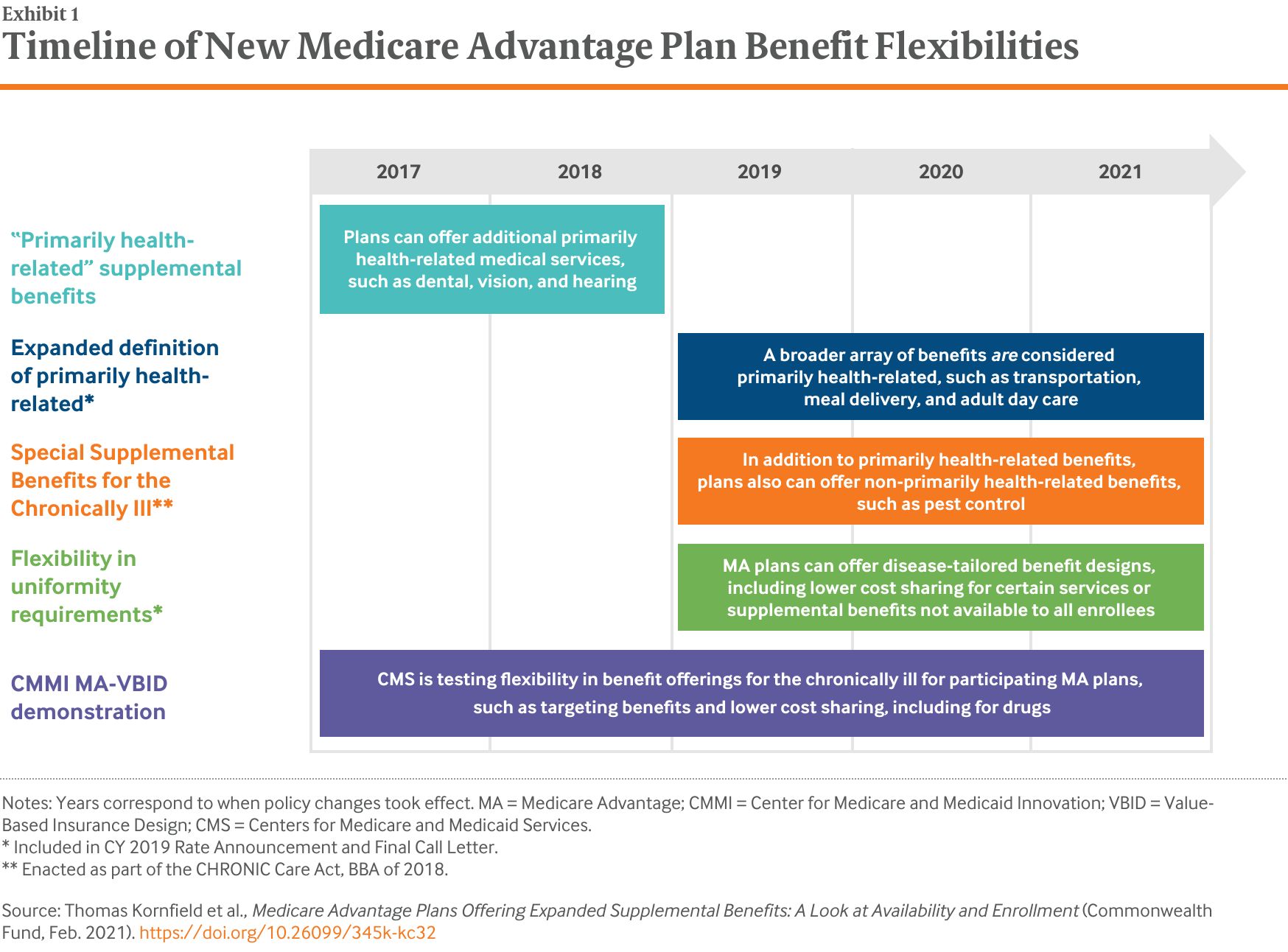

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans are seeing increasing numbers of enrollees who have social risk factors and complex medical needs.3 Recently, both Congress and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have granted these plans new flexibilities in designing benefits, with the goal of improving outcomes and lowering costs, particularly for enrollees with chronic conditions (Exhibit 1). In 2017, CMS began allowing MA plans participating in the Value-Based Insurance Design (VBID) model — a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation demonstration program — the ability to offer benefit designs tailored to specific diseases, such as reduced cost sharing and deductibles for certain specialist visits or prescription drugs. Then, in 2019, CMS extended to all MA plans the ability to offer disease-tailored benefit designs.

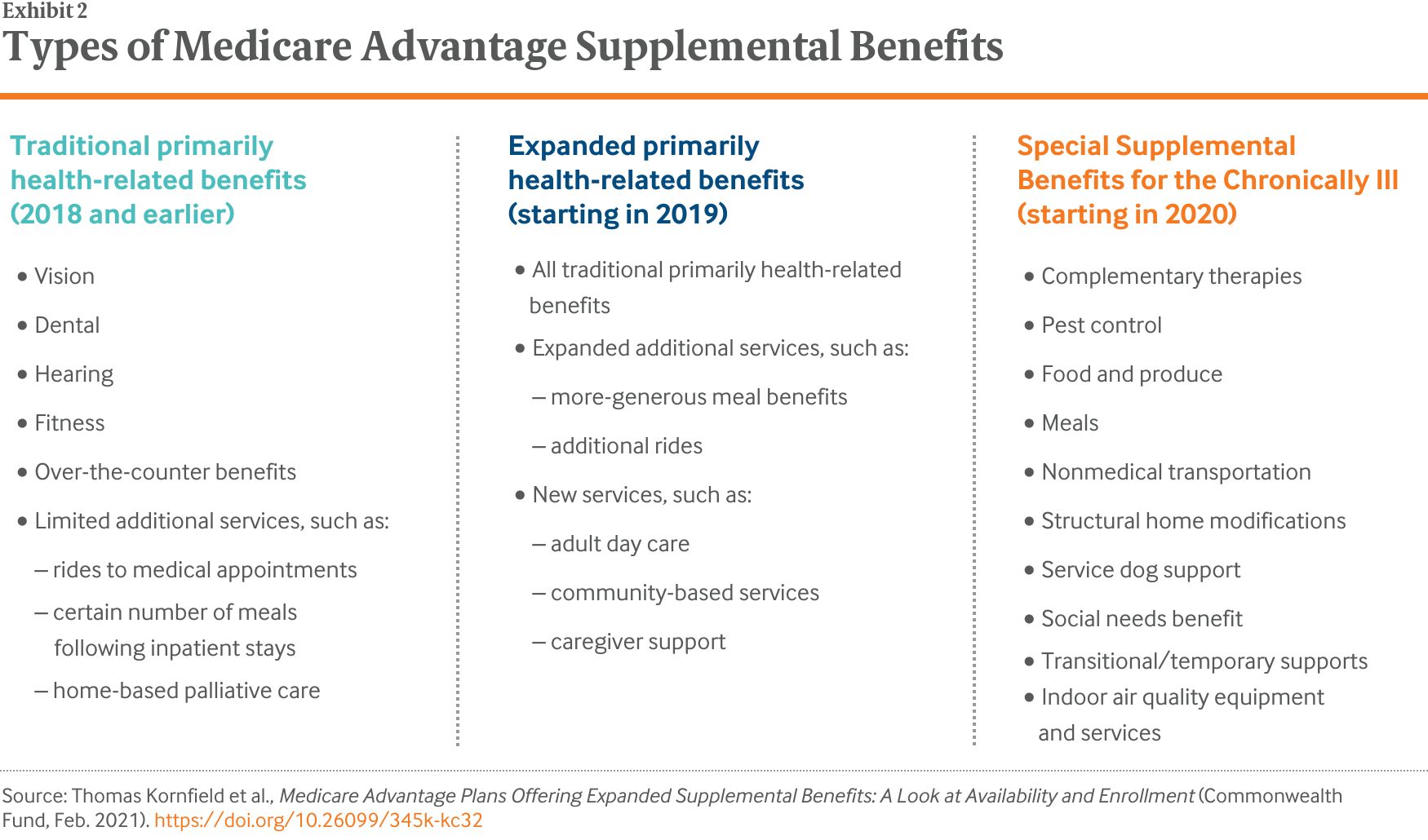

CMS also expanded the types of benefits that plans can offer. While MA plans have long been able to offer “primarily health-related” supplemental benefits not covered by fee-for-service Medicare, such as vision and dental coverage, these benefits until recently were narrowly defined by CMS to cover only medical services and had to be available to all plan enrollees. Starting in plan year 2019, CMS expanded primarily health-related to include nonmedical services. Under this new definition, plans can offer a wider array of supplemental benefits as long as these benefits are intended to “diagnose, prevent, or treat an illness or injury, compensate for physical impairments, act to ameliorate the functional/psychological impact of injuries or health conditions, or reduce avoidable emergency and health care utilization to all beneficiaries.”4 In practice, this interpretation allows plans to offer nonmedical benefits, such as broader use of transportation or meal delivery, in addition to the previously allowed medical benefits (Exhibit 2).5

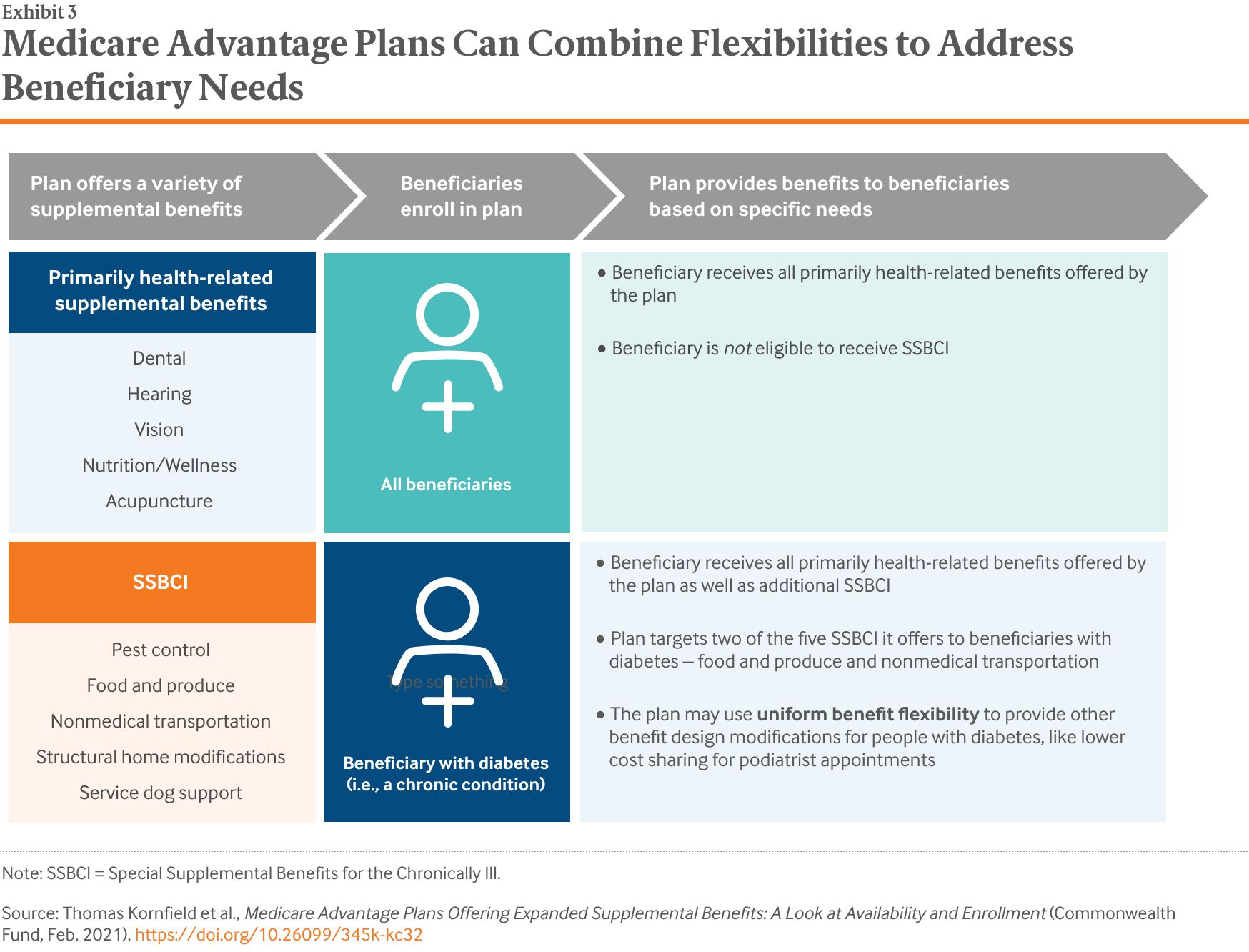

Meanwhile, with the passage of the Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act, plans, as of 2020, can offer Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI). Plans may choose to offer these benefits to enrollees with certain chronic conditions, and the benefits do not have to be primarily health-related, as long as the item or service can reasonably improve or maintain health or function of the enrollee.6 As a result, insurers can now tailor both medical and nonmedical benefits to certain enrollees (Exhibit 3).

This issue brief provides an overview of MA supplemental benefit offerings from 2018 to 2020. We examine how MA plans have responded to increased flexibilities as well as the extent to which plans offer these new, nonmedical benefits alongside traditional medical benefit offerings. Notably, the 2020 data included in these analyses reflect pre-COVID-19 plan offerings and enrollment.