Selective border crossing raises different concerns than a wholesale market merger. If selective crossing is done strategically to take advantage of different market rules, the results could weaken or undermine those rules. Two particular measures, however, appear to lower fences without risking significant adverse selection. The first is allowing self-employed individuals to purchase small-group coverage as a “group of one.” The second is to allow small employers to subsidize workers’ purchase of individual insurance through health reimbursement arrangements (HRAs). We discuss each in turn.

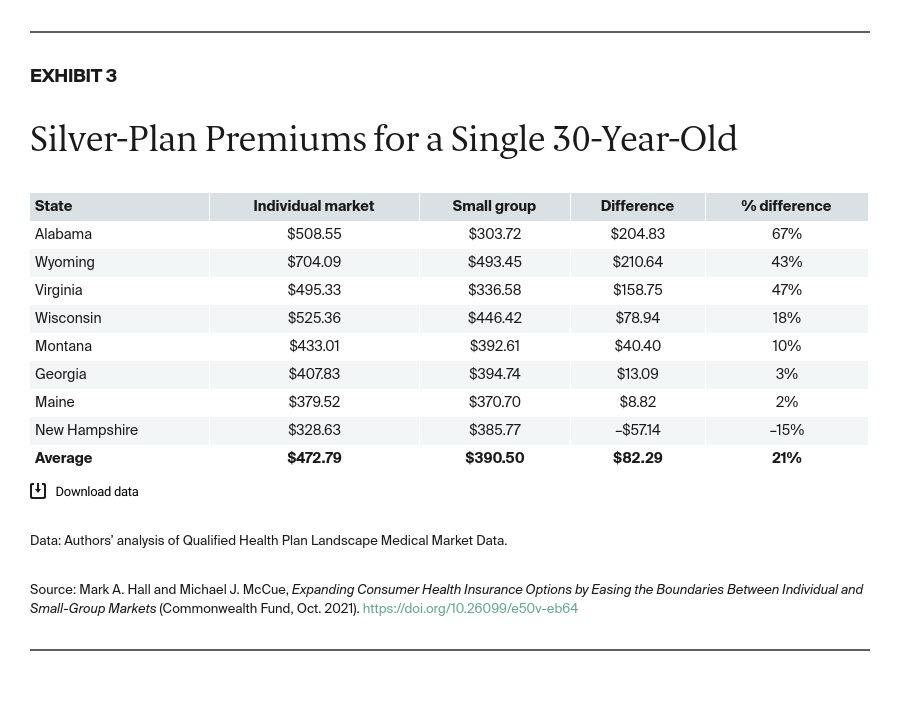

Group-of-one rule. Prior to the ACA, 16 states allowed self-employed individuals to purchase group coverage through their sole proprietorships, denominating these as “groups of one.”13 The ACA, however, defined groups as having at least two independent members (e.g., owner plus an unrelated employee). Most or all of these states changed their small-group rules to conform with the federal definition, but Virginia expanded small-group coverage to include the self-employed as a way to provide more affordable options.14 Also, a few states (e.g., Iowa, Texas, and Utah) loosened the ACA’s owner-plus-employee requirement for group status to include so-called mom-and-pop businesses, in which the only employees are the owners themselves.15 Some brokers report that this flexibility is helping self-employed people find “more affordable [or] generous coverage.” In addition to price, another potential advantage of small-group coverage is that it often offers broader provider networks, such as preferred provider organizations (PPOs), rather than only health maintenance organizations (HMOs).

The only concern that has been raised about returning to, or adopting, a group-of-one rule for the small-group market is that doing so conflicts with the ACA and thus might be beyond state authority.16 One solution to that problem is for Congress to amend the ACA. Pending that, however, the Virginia Bureau of Insurance ruled that its group-of-one rule does not contravene the ACA because it expands rather than contracts small-group options, and so far federal authorities have not objected.17 Thus, this option appears to be readily available to states.

Health reimbursement arrangements. HRAs are tax-sheltered accounts through which employers can subsidize workers’ health-related expenses without those subsidies counting toward workers’ taxable income. If employers earmarked HRA funds for health insurance premiums, then workers could purchase individual coverage with pretax rather than after-tax funds, producing a substantial discount equivalent to each worker’s federal and state tax bracket, plus payroll taxes. Initially, however, federal agencies prohibited this arrangement, out of concern that employers who previously were offering health insurance would dump their workers onto the subsidized individual exchanges. Congress adopted a solution to that problem, though, with a 2016 enactment that allowed qualified small employer HRAs (QSEHRAs) under limited conditions.18 QSEHRAs cannot be offered selectively to only some employees, and the employer’s contribution reduces pro rata any premium subsidy a worker might be eligible for through the ACA exchange.

So far, QSEHRAs have received only limited uptake. One reason is their complexity.19 QSEHRAs differ from conventional HRAs, which themselves differ from flexible spending accounts (FSAs, also known as cafeteria plans) and health savings accounts (HSAs). Understanding, navigating, and administering all of these different employee benefit arrangements can be daunting, especially in view of the additional requirements imposed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA), and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

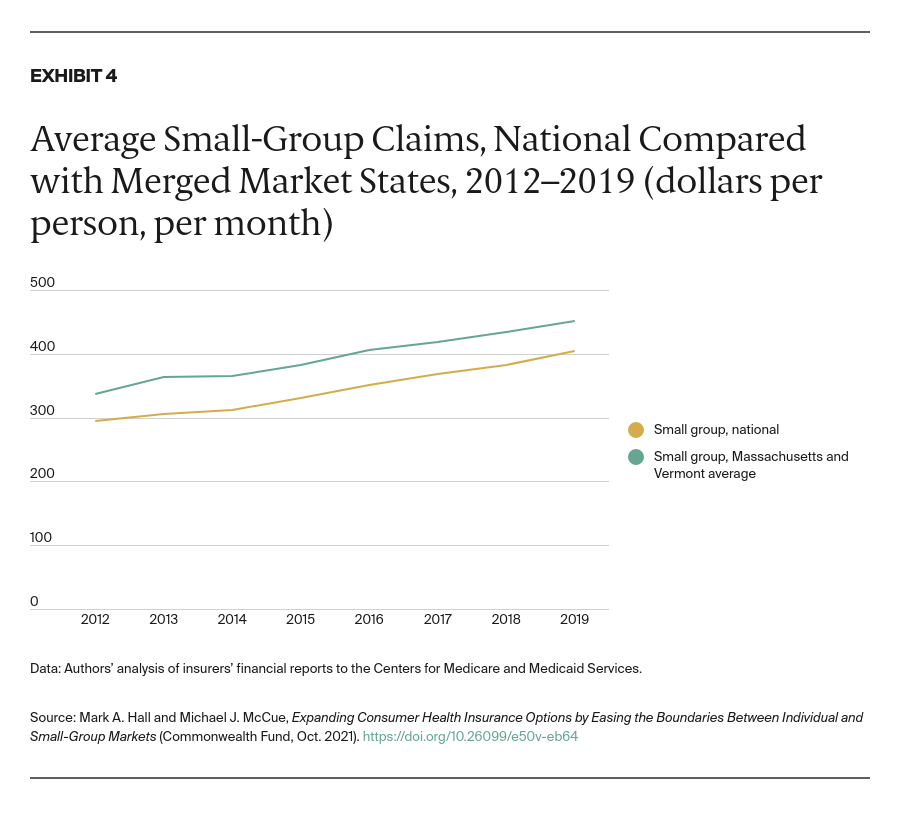

Moreover, QSEHRAs were followed by a similar but distinctive HRA version known as individual-coverage HRAs (ICHRAs), created by a 2019 regulation.20 ICHRAs accomplish the same basic goal of QSEHRAs but are available to employers of any size. Because ICHRAs were created by regulation rather than statute, however, they are subject to a somewhat different set of constraints. And, because ICHRAs reduce market boundaries between the large-group and individual markets, they raise different public policy concerns than QSEHRAs.21 For instance, because larger groups are not subject to the same community rating rules that govern the individual market, allowing larger employers to fund individual insurance through HRAs could lead to some degree of adverse selection.

Conclusion

Interest is growing in policy options to ease boundaries between the individual and small-group markets. Self-employed individuals who do not qualify for subsidized insurance could benefit from being able to purchase group insurance as a group of one. Or small firms with workers who might qualify for federal subsidies could provide more affordable coverage choices by helping workers to purchase individual coverage. Moreover, bringing more employer-subsidized purchasers into the individual market could stimulate more innovation and competition between insurers.

For small businesses to take full advantage of these opportunities, however, tax and regulatory rules need streamlining and simplification. The time may be right to rethink and redesign these policies in a way that avoids regulatory strictures designed to address problems that no longer exist.