Introduction

Midwives are licensed health care providers who offer a wide range of essential reproductive and sexual health care services, from birth and newborn care to Pap tests and contraceptive care. Research consistently demonstrates that when midwives play a central role in the provision of maternal care, patients are more satisfied, clinical outcomes for parents and infants improve, and costs decrease.1 Use of midwives is also associated with fewer cesarean sections, lower preterm birth rates, lower episiotomy rates, higher breastfeeding rates, and a greater sense of respect and autonomy for the patient.2

It’s not difficult to imagine that midwifery could play a role in addressing tenacious perinatal health disparities in the United States. In 2021, the U.S. had 32.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 births, more than 10 times that of countries like Australia, Japan, Israel, and Spain, where rates remain between two and three per 100,000.3 Maternal mortality rates are rising across all races and ethnicities in the U.S. — Black women are dying at nearly triple the rate of white women, and Native American women at double the rate. Additionally, data from maternal mortality review committees suggest that four of five pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.4

A recent analysis found that a midwife workforce, integrated into health care delivery systems, could provide 80 percent of essential maternal care around the world and potentially avert 41 percent of maternal deaths, 39 percent of neonatal deaths, and 26 percent of stillbirths.5 Midwives also could help address the workforce shortages that loom large in the U.S. maternity care landscape: nearly half of U.S. counties lack a single obstetrician-gynecologist, and it’s estimated that the nation needs 8,000 more to meet demand — a number that, by one estimate, may rise to 22,000 by 2050.6

However, unlike other high-income countries such as Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, the United States does not systematically incorporate midwives into essential maternity care services. Lack of comprehensive insurance coverage for midwifery services, restrictive and archaic state and federal regulations that limit the practice of midwifery, and an absence of public subsidies for midwifery education are just a few of the reasons. A multitude of social, political, historical, and economic factors are also at play, including the shift from community-based care to hospital-based care, the medicalization of childbirth that defined pregnancy as inherently risk-laden needing medical and technological interventions, and the history of sexism and racism in medicine. These factors systemically eroded the midwifery profession and nearly decimated the community-centered approach used by Black midwives in the South and immigrant midwives in the Northeast.7 Today, as a result, only 11 percent of births in the U.S. are attended by a midwife and only 2 percent of births occur outside of hospital settings.8

Given the many benefits of midwives, and the profound maternal care inequities affecting Black and Indigenous families in the U.S., it’s important to understand how they could be better integrated into the U.S. health care system. This includes the intentional integration of midwifery across the complex health care ecosystem in order to ensure midwifery care is accessible, affordable, and equitable to all childbearing people.

The Midwifery Model of Care

The midwifery model takes a holistic, relationship-centered approach to the pregnancy and birthing continuum.9 Its philosophy of care is rooted in four principles:

- Care that is built on a trusting and respectful relationship between the midwife and the childbearing person.

- Care that prioritizes and encourages the parent’s autonomy, self-determination, and satisfaction.

- Informed decision-making in partnership with the childbearing person.

- An environment of care that creates a sense of safety and assurance for client and midwife.10

In addition to caring for people during pregnancy and childbirth, midwives in the U.S. can: conduct physical examinations; prescribe medications, including controlled substances and contraceptives; admit, manage, and discharge patients; order and interpret laboratory and diagnostic tests; and order the use of medical devices. However, state and hospital policies often limit the capacity of midwives to practice to their full scope.

Three-quarters (76%) of certified nurse-midwives/certified midwives (CNMs/CMs) in the U.S. undertake reproductive care in their full-time positions, and 49 percent have primary care responsibilities.11 This could include the independent provision of sexual and reproductive health, which also includes primary gynecological care, family planning services, preconception care, care of newborns during the first 28 days of life, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

Midwives have a long history of providing high-quality, high-touch care to meet both the physiological and psychosocial needs of historically disenfranchised communities.12 Additionally, demonstration projects of nurse-midwifery services located in underserved, poorly resourced communities in California, Georgia, Kentucky, and New York consistently showed safe neonatal and maternal outcomes.

Midwifery in the U.S.

While midwifery in the United States is often associated with births in the community, including in homes and birth centers, 87 percent of midwife-attended births in 2020 were in hospital settings in collaboration with nurses and physicians.13 In fact, most of the U.S. midwifery workforce (95%) reports working exclusively in hospital settings.

There are three different midwifery credentials in the U.S.: certified nurse-midwives (CNMs), certified midwives (CMs) and certified professional midwives (CPMs). Although they have different educational and regulatory pathways, they have similar competencies and a shared commitment to a person-centered, midwifery care model. Most CNMs/CMs attend births in hospitals, with a smaller number providing care at homes and at birth centers. CNMs/CMs also provide primary care and primary women’s health care, including contraception and abortion. Scope of practice for CPMs is in most cases focused on care across the course of a pregnancy and newborn care in community settings like homes and birth centers.14

The COVID-19 pandemic saw a notable increase in people choosing to give birth outside of hospital settings. Community births increased by 19.5 percent in 2020 — planned homebirths by 23.3 percent and deliveries in birth centers by 13.2 percent. Increases occurred in every state and for all racial and ethnic groups, most dramatically for non-Hispanic Black birthing parents (29.7%). This shift was linked to concerns about contracting the coronavirus in hospital settings, protocols like limitations or bans on support people in the hospital, and the separation of infants from mothers suspected to be COVID-positive. These factors likely spurred interest in, and greater acceptance of, giving birth in community settings with midwives.15

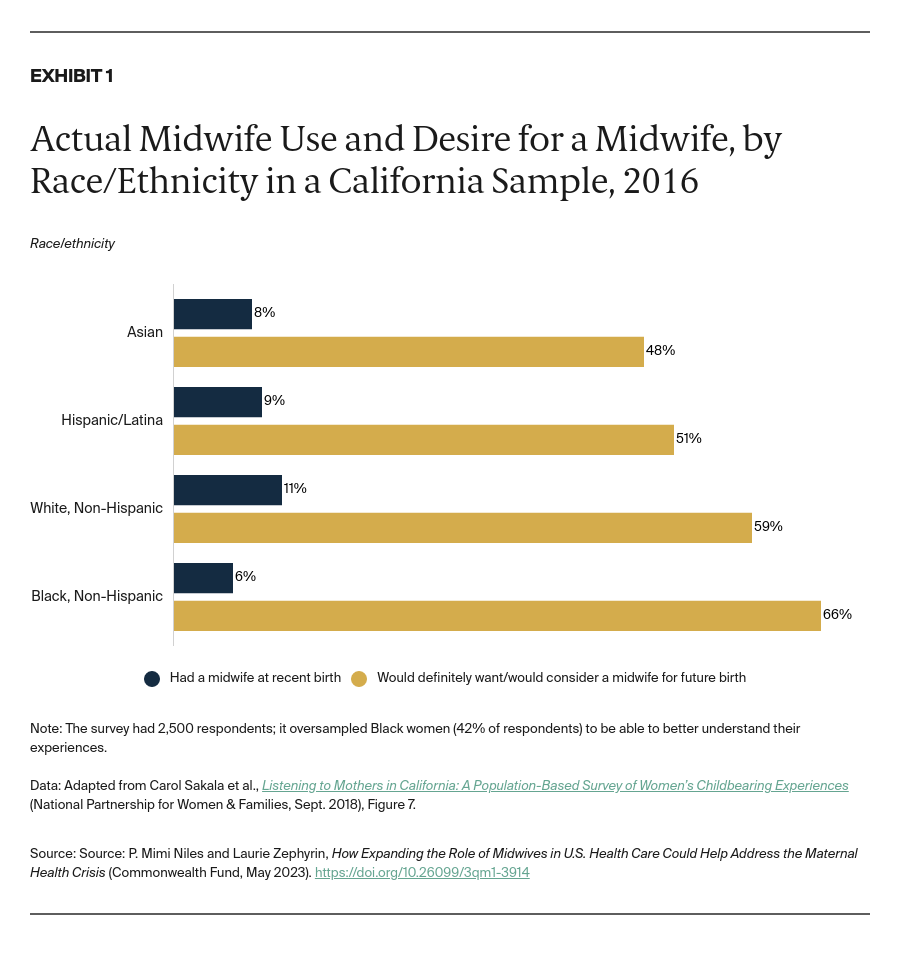

While demand for midwifery care in both hospital and community settings grows, much of it remains unmet. A California-wide survey recently demonstrated significant mismatch between the desire to be cared for by a midwife and the actual use of midwifery in childbirth, with Black childbearing people experiencing the biggest gap between demand and access (Exhibit 1).16