Licensed agents (also known as brokers) and agencies can help Medicare beneficiaries choose the right coverage. Agents are individuals who are licensed and registered to solicit and enroll people into insurance products. Agencies provide administrative support such as marketing, technology infrastructure, compliance, and other services for agents. Medicare plans contract with agents and agencies to reach and enroll beneficiaries; in return, agents earn commissions directly from insurers. Independent agents and agencies represent multiple (but not necessarily all) insurers and help beneficiaries compare and enroll in options in their area. In this capacity, they represent both plans and beneficiaries, with compensation tied exclusively to enrollments with contracted insurers. As a result, agents may find themselves choosing between their income and beneficiaries’ needs.

How Medicare Advantage, Medicare Part D, and Medigap Commissions Are Set

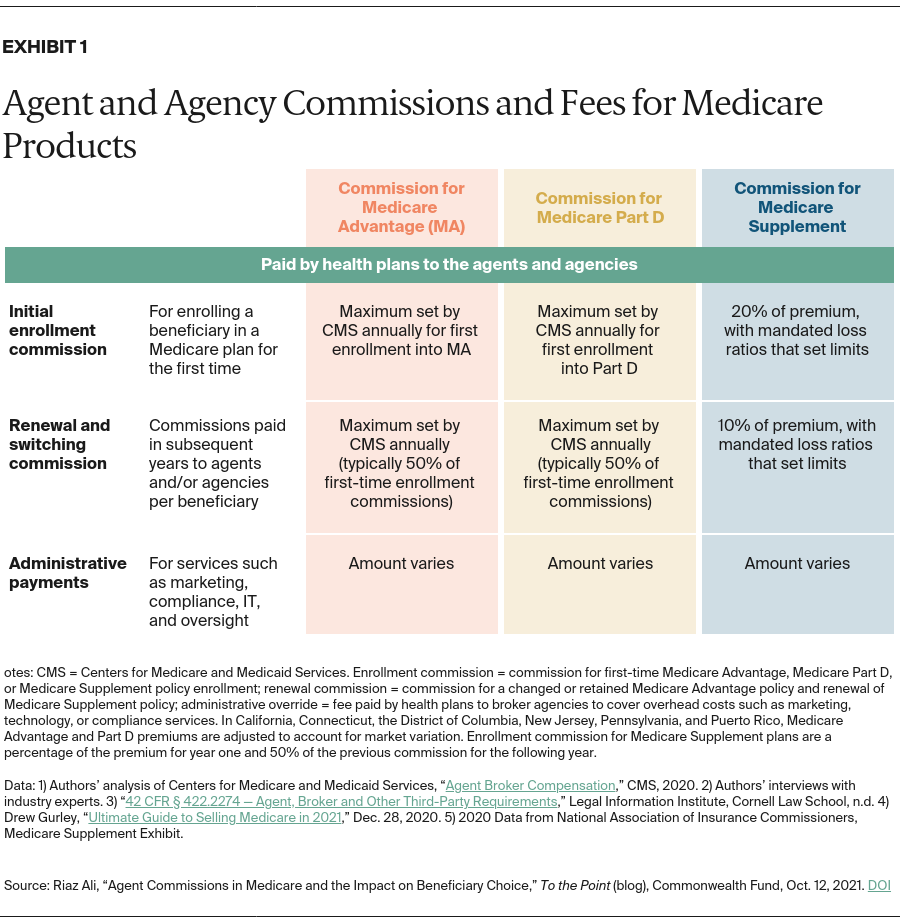

Agents’ compensation for Medicare Advantage (MA), Medicare Part D, and Medigap (also known as Medicare Supplement) is tied to enrollment and retention of beneficiaries and is paid by insurers. Maximum commissions for MA and Part D are set annually by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and are commensurate with fair market value (FMV). Within the maximums set by CMS, insurers determine the exact compensation level they will pay agents, which can vary by product or contract. CMS maximums are set nationally, although they may be higher in certain states because of cost of living and other conditions. For example, for 2022, CMS has set the maximum national commission for first-time enrollment in MA at $573 per beneficiary for most parts of the country. In California, however, the maximum first-time commission is $715. For standalone Part D plans, the 2022 maximum national commission for first-time enrollment is $87 and does not vary by region. These commissions are paid when the beneficiary first enrolls in an MA or Part D plan.

Once a beneficiary is enrolled in an MA or Part D plan, agents earn a commission when the beneficiary switches to a new plan or stays with the original plan. The commission is paid to the agent of record as long as the beneficiary does not have an enrollment submitted to a new insurer by another agent. CMS maximum commission rates are set lower for “switchers” and “renewals” — 50 percent of the first-time commission. For 2022, the maximum national commission for renewals and switches is $287 for MA, with variations in certain markets. For example, in California, the renewal commission is $358. For Part D, the national maximum renewal commission is $44.

For Medigap plans, the agent’s commission is typically a percentage of the annual plan premium; the percentage is set and the commission paid by the insurer. Unlike MA and Part D, the rates are not set by CMS or individual states. A recent report indicates that first-year commissions for enrollments in Medigap are approximately 20 percent of annual premiums, but they can vary based on the state or plan type. The commission for subsequent years (i.e., the renewal commission) is set at 10 percent of the premium. Based on our analysis, the average premium in 2020 for Medigap was $1,660, meaning an agent would be paid $322 for the first year and $166 as a renewal commission. Because premiums and rate adjustments for policies can vary, commissions may shift based on beneficiary, policy, and location.

Additional Administrative Payments by Insurers to Agencies and Agents

Insurers also may make additional payments, in addition to enrollment commissions. These administrative payments are paid to agencies for assuming administrative and operational responsibilities in support of an agent’s work soliciting and enrolling beneficiaries. These activities may include marketing, technology, training, and compliance; the agencies serve as an intermediary between agents and insurers.

Unlike enrollment commissions, administrative payments are not set by any governing or regulatory body; instead, they are set by insurers in negotiation with each independent agency. For MA and Part D, CMS’s Medicare marketing guidelines establish that these payments “must not exceed FMV or an amount that is commensurate with the amounts paid to a third party for similar services during each of the previous two years.” These payments provide another channel of financial support between insurers and agencies and agents.

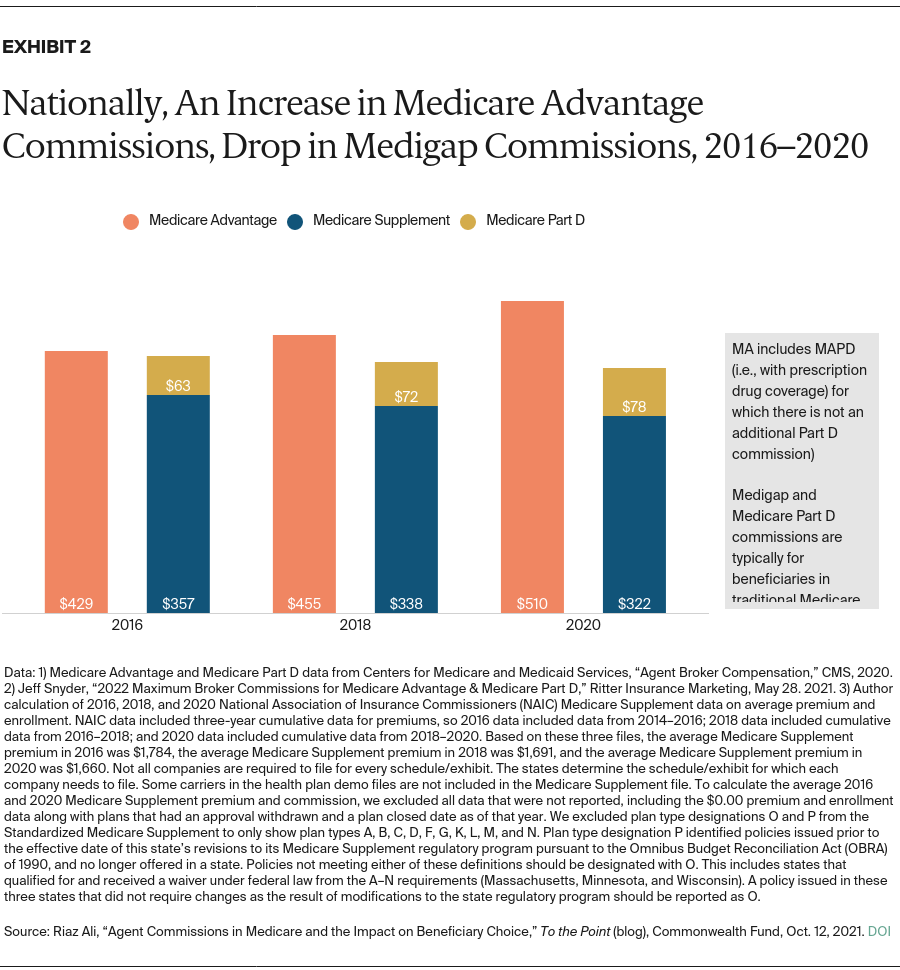

Commissions for Medicare Advantage vs. Medigap

Given that agents and agencies’ commissions are set and regulated differently across MA and Medigap, it is important to consider whether there is a material financial incentive for agents to enroll beneficiaries in a MA plan versus traditional Medicare with Part D and Medigap. Our analysis from 2016, 2018, and 2020 suggests that since average premiums in Medigap have dropped, agent compensation (a percentage of the premiums) also has decreased. Conversely, while MA premiums have decreased, agent compensation (set by CMS) has risen at a rate that has surpassed inflation.1

Implications

Our analysis has four core implications for policymakers.

First, the difference in MA and Medigap compensation creates a potential conflict — the agent may be motivated to recommend one type of coverage or another based on the compensation rather than the beneficiary’s need. CMS could consider setting commissions to ensure that agents are not motivated financially to favor a particular type of coverage, and therefore, can provide beneficiaries unconflicted advice.

Second, through commissions and administrative payments, insurers can align agents’ financial incentives around their business priorities (e.g., growth of a particular MA product over another, or growth of MA business over Medigap). This could create another conflict of interest. Increasing transparency and reporting on carriers’ actual compensation payments — as opposed to the CMS-defined maximums — across MA, Part D, and Medigap could help address this. Policymakers also should consider additional regulatory clarity around the administrative payments, bonuses, and other forms of compensation.

Third, beneficiaries’ experience with their agents and the overall quality of the service are not factored into the commission model, although there is precedence for this within Medicare. For example, MA and Part D plans are measured through the star ratings program and are compensated differently for delivering a high-quality member experience. Pay-for-performance could be considered part of the compensation model for agents and agencies.

And fourth, the renewal–commissions model is a double-edged sword. Ensuring commissions even if beneficiaries stay with their original plans may help prevent unnecessary switching. However, there is also a risk that agents have limited incentive to revisit plan fit or routinely check in with beneficiaries. Policymakers could consider defining a minimum level of service required to earn the renewal or switching commission.

Agents are an important resource for beneficiaries, but we should reimagine compensation to ensure that incentives are more closely aligned with the aims of providing guidance and counsel to beneficiaries and without the risk of competing financial interests.