The House debt ceiling bill includes work requirements for certain Medicaid recipients. The requirements would apply to enrollees who do not have dependents and who are 19 to 55 years old, physically and mentally fit for employment, not pregnant, not enrolled in an education program, and not participating in a drug or alcohol treatment and rehabilitation program. Under the House bill, these Medicaid enrollees would have to work or participate in community service or work programs for at least 80 hours per month to remain eligible for benefits. Most of those exempt from the work requirements would need to provide evidence to maintain eligibility, often including medical documentation, and states would have to pay for the additional paperwork and additional medical visits.

Prior research has shown that Medicaid work requirements do not increase employment rates. Rather, beneficiaries who lose eligibility generally become uninsured. Since Medicaid coverage substantially increases access to care for otherwise uninsured populations, withdrawing coverage leads to reductions in the care people receive. Medicaid also provides financial protection to beneficiaries and medical providers, reducing bankruptcies and evictions for individuals and uncompensated care for providers.

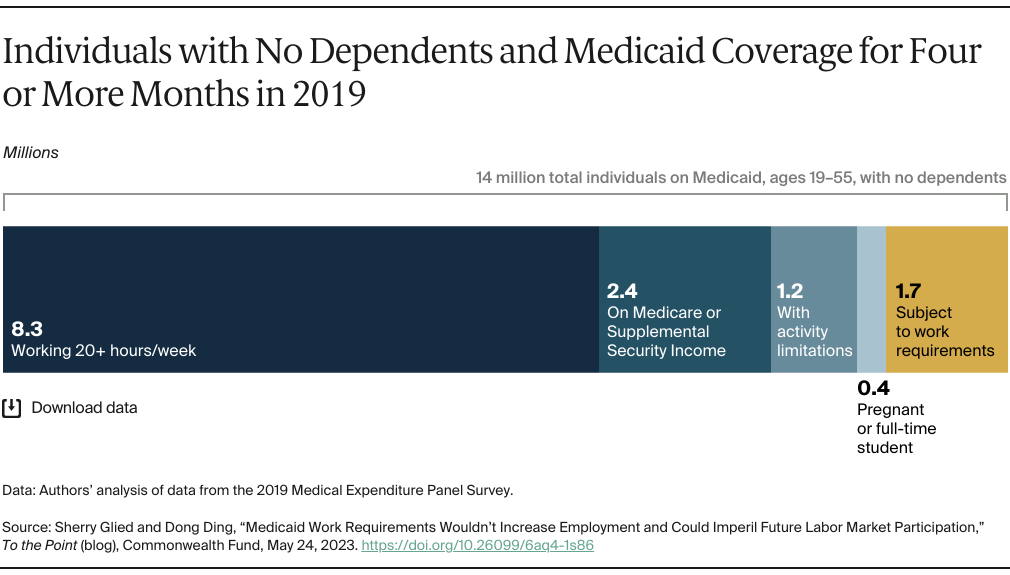

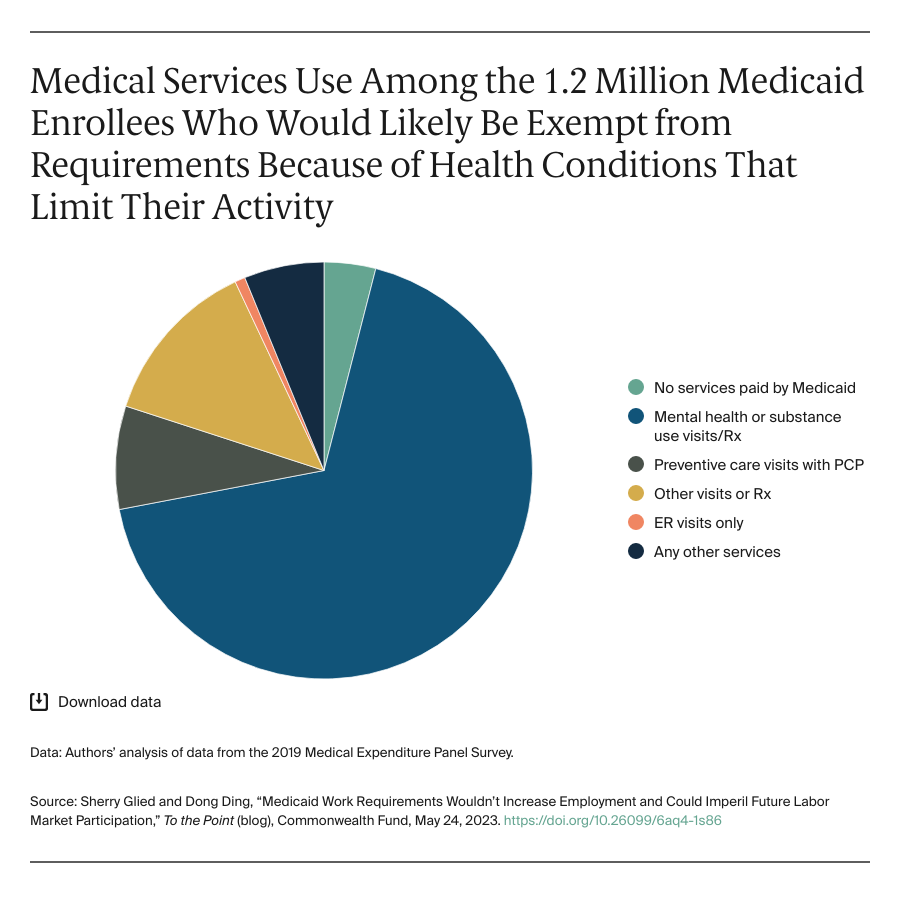

For this post, we looked at the patterns of care used by people likely to lose Medicaid benefits under the work requirements to illustrate what the provision would mean to beneficiaries, care providers, and the Medicaid program.

Most Beneficiaries Are Working or Qualify for Exemptions

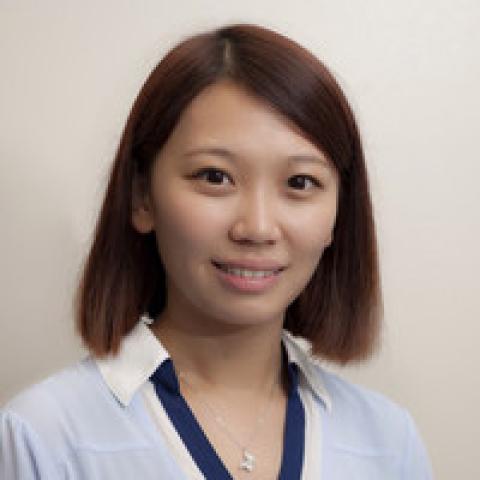

Using the 2019 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, we estimated that about 14 million of the 68 million Medicaid enrollees who were enrolled for at least four months in that year fell into the relevant age range and did not have dependents. Most of them worked more than 20 hours per week. About 5.7 million reported not working or working fewer than 20 hours.

Of this small group, many would qualify for an exemption from work requirements: 2.4 million were enrolled in Medicare or the Supplemental Security Income program and 1.2 million reported that they had activity limitations. Finally, 0.4 million people would be exempt because they were pregnant or were attending school full-time. Consequently, of the original 14 million, the majority (about 12.3 million) would be exempt from the work requirements.