By Adriano Massuda, Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV-EAESP) Business Administration School of São Paulo, Mônica Viegas Andrade, Center for Regional Development and Planning CEDEPLAR, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Rifat Atun, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and Marcia C. Castro, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health

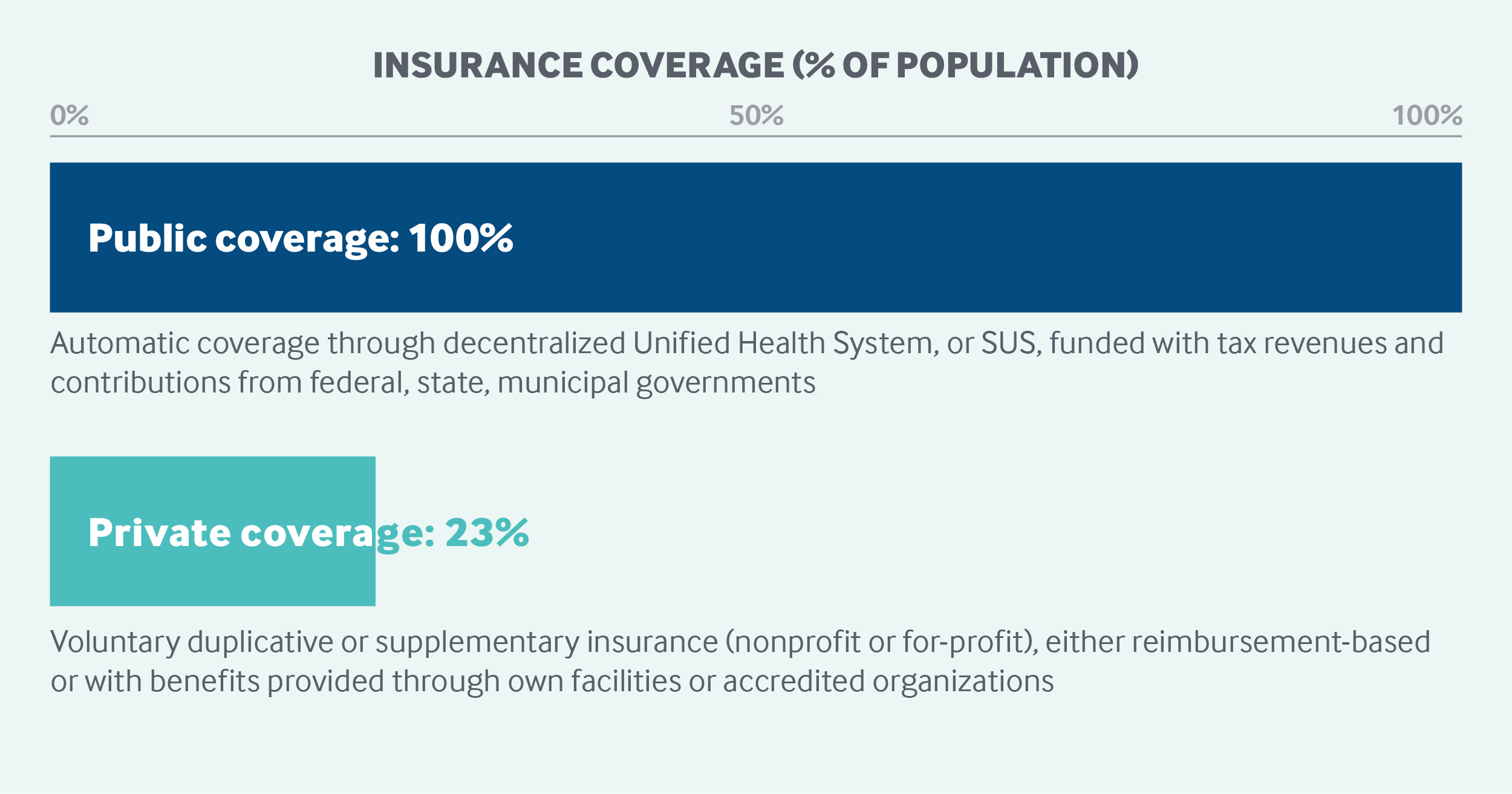

Brazil’s decentralized, universal public health system is funded with tax revenues and contributions from federal, state, and municipal governments. The administration and delivery of care are handled by municipalities or states. All residents and visitors, including undocumented individuals, can access free, comprehensive services, including primary, outpatient specialty, mental health, and hospital care, as well as prescription drug coverage. No application process is necessary. There is no cost-sharing for health care services. Nearly 25 percent of Brazilians, mostly middle- and higher-income residents, have private health insurance to circumvent bottlenecks in accessing care. Private health insurance costs, as well as health-related purchases, qualify as tax deductions.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

The constitution of Brazil defines health as a universal right and a state responsibility.1 The Brazilian health system, known as SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde), was conceived during the 1980s as part of the social movement aimed at Brazil’s re-democratization. SUS was officially created in 1988 by the new Brazilian constitution.

Three principles underpin SUS:

- The universal right to comprehensive health care at all levels of complexity (primary, secondary, and tertiary).

- Decentralization with responsibilities given to the three levels of government: federal, state, and municipal.

- Social participation in formulating and monitoring the implementation of health policies through federal, state, and municipal health councils.

Since 1990, the incremental expansion of SUS has enabled substantial progress toward achieving universal health coverage.

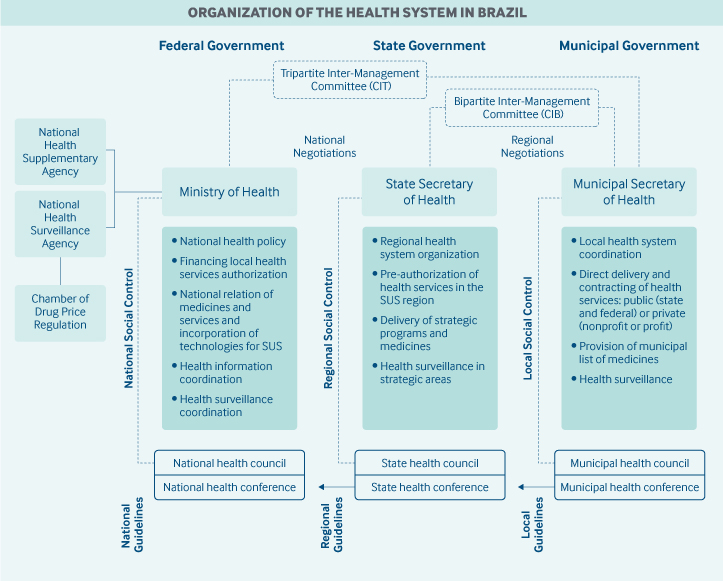

Role of government: The Ministry of Health is responsible for national coordination of SUS, including policy development, planning, financing, auditing, and control. State government duties include regional governance, coordination of strategic programs (such as provision of high-cost medicines), and delivery of specialized services that have not been decentralized to municipalities. The health departments in the 5,570 municipalities largely handle the management of SUS at the local level, including cofinancing, coordination of health programs, and delivery of health services.

Community participation in the public health system is guaranteed by the constitution at all levels of government. Health councils and health conferences are composed of 50 percent community members, 25 percent providers, and 25 percent health system managers. These councils and conferences are responsible for deliberating public health policies and monitoring their implementation.

Role of public health insurance: In 2015, health spending in Brazil was 9.1 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP),2 of which public spending accounted for 42.8 percent. SUS covers all types of health care for all residents and visitors, including undocumented people. No application process is needed to access health services.

Approximately 75 percent of Brazilian citizens rely solely on SUS. Bottlenecks in access and dissatisfaction with health services have prompted middle-income and high-income households to seek private care.3,4

The public system is financed by tax revenues and social contributions from all three levels of government. The minimum contribution rates for health expenditures are defined in law as follows:

- Federal: 15 percent of net current government income in 2017, adjusted for annual inflation.

- State: 12 percent of total revenue.

- Municipal: 15 percent of total revenue.

Over the past 30 years, the share of federal funding has declined, while funding from municipalities has increased. In 2017, the federal share was about 43 percent of total public expenditures, while states contributed nearly 26 percent and municipalities 31 percent. As a result, although municipalities are required to spend at least 15 percent of their own total revenues on health, in reality they spend, on average, nearly 24 percent.5

Role of private health insurance: Private health insurance is voluntary and supplementary to SUS and regulated by the National Agency of Supplementary Health. In 2018, 23 percent of Brazilians had private medical/hospital insurance, and 9.6 percent had dental insurance. Nearly 70 percent of beneficiaries receive their private health insurance as an employment benefit.

Private health plans offer health care services through their own facilities or through accredited health care organizations. Alternatively, private insurance can reimburse enrollees for purchased health care services.

Brazil spends 0.5 percent of GDP on tax exemptions for private health care, primarily to subsidize those who pay for private health insurance.6 Individuals and legal entities may deduct health insurance costs as well as the purchase of health services, medicines, and medical supplies from their taxable expenses.

Services covered: SUS offers a broad spectrum of health services free of charge, including7:

- preventive services, including immunizations

- primary health care

- outpatient specialty care

- hospital care

- maternity care

- mental health services

- pharmaceuticals

- physical therapy

- dental care

- optometry and other vision care

- durable medical equipment, including wheelchairs

- hearing aids

- home care

- organ transplant

- oncology services

- renal dialysis

- blood therapy.

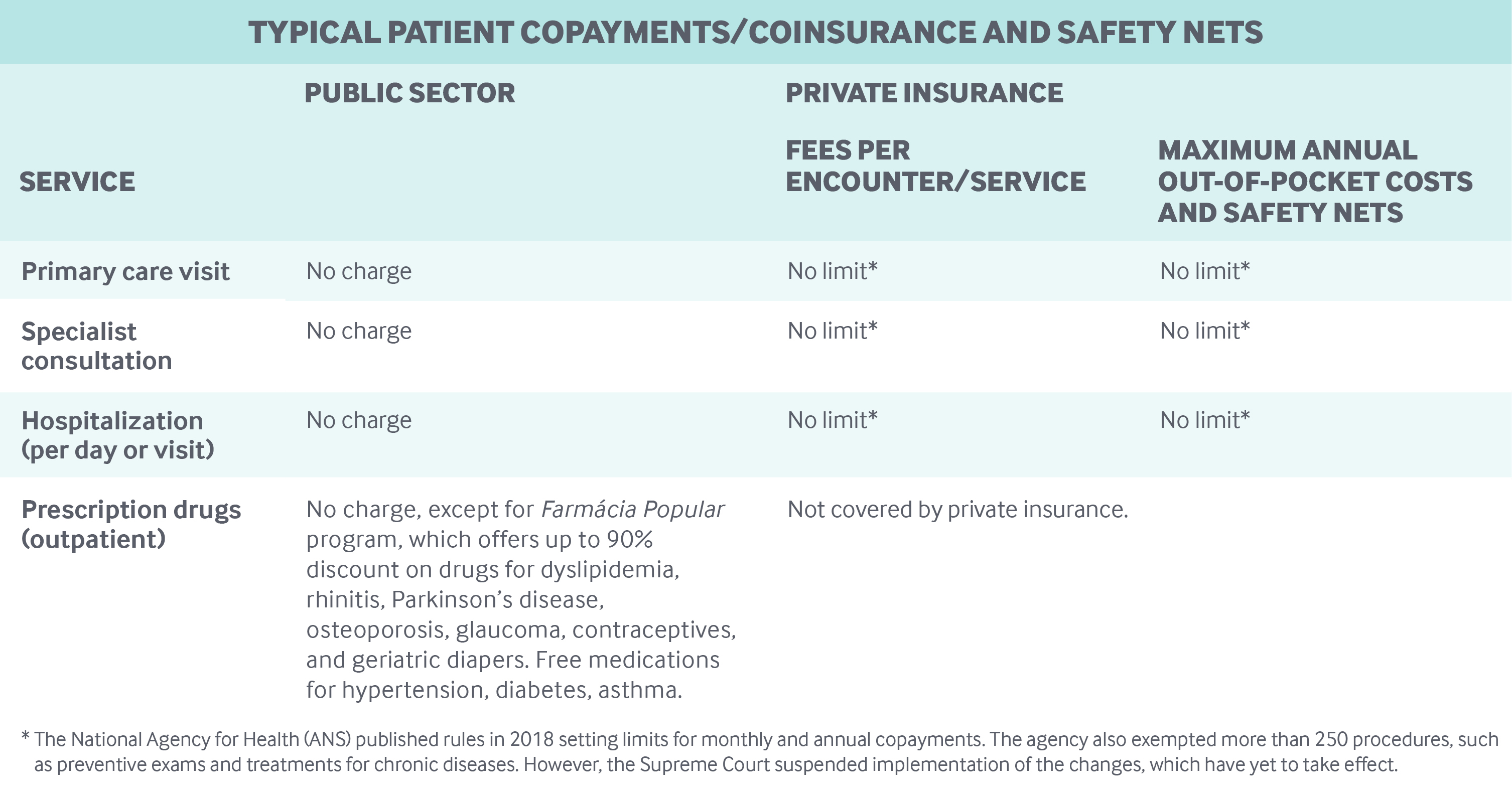

The expansion of pharmaceutical coverage by the SUS was a pioneering initiative, as Brazil was one of the first middle-income countries in the world to offer free access to HIV/AIDS medication, beginning in 1996. Between 2002 and 2017, the list of essential medicines and medical products grew from 327 to 869. In addition, the Popular Pharmacy of Brazil program provides subsidized contraceptives as well as drugs for dyslipidemia, rhinitis, Parkinson’s, osteoporosis, and glaucoma, and free medication for hypertension, diabetes, and asthma.

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: Out-of-pocket expenditures account for a little more than 27 percent of total health expenditures.8 However, they represent a considerable financial burden for households, and disproportionately affect the poor. In 2014, 5.3 percent of households experienced such high health expenditures that they had to forgo paying for non-health-related items. The cost of medications was a primary contributor, as only certain drugs are available free of charge under SUS.9

Conversely, in the last 10 years, the share of private health care plans charging copayments has grown from 22 percent to 52 percent.10 However, no clear rules exist for setting copay limits in private insurance.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: In 2018, Brazil had 451,777 registered physicians (2.18 physicians per 1,000 inhabitants). Of this number, about 63 percent were specialists and 37.5 percent were general practitioners.

The number of medical schools is growing exponentially, driven mainly by the opening of private institutions. In 2017, there were 289 medical schools, offering more than 29,000 training positions. Of these schools, 35 percent were in public universities and 65 percent are private medical schools.11 In 2019, about 80 percent were private institutions.12 Education and training at public medical schools are free. Tuition at private medical schools varies from USD 1,400 to USD 3,000 (BRL 6,000 to BRL 13,000) per month.13

The geographic distribution of doctors is highly skewed toward larger and wealthier cities. For instance, in 2018, there were one physician per 3,000 individuals in municipalities with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants. In comparison, there were one physician per 230 individuals for municipalities with more than 500,000 inhabitants. This disparity largely reflects the location of medical schools.

The Brazilian government has instituted several initiatives to address the shortage. Several national policies foster physician education, including specialty residencies. In addition, the federal government has begun efforts to ensure a greater supply of primary care physicians and to regulate the location of medical schools, establishing new rules and incentives to open schools in municipalities where health care needs are greatest.14

Primary care: The Family Health Strategy, implemented in 1994, is the national policy for the expansion of primary care in SUS. The model promotes the use of family health teams, made up of one doctor, one nurse, one nurse assistant, and up to 12 community health workers. The teams cover 2,000 to 4,000 individuals in households across a geographic area. Oral health teams of one dentist and one or two dental assistants may also be assigned to patient populations.

Further specialized services may be provided by support staff, including nutritionists, psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists, pharmacists, speech and hearing therapists, gynecologist/obstetricians, pediatricians, geriatricians, and others according to local needs.

To encourage the implementation of the team model, the federal government provides funding on a per-capita basis. On a monthly basis, up to BRL 10,695 (USD 2,493) per family health team is transferred to the municipalities, which are responsible for organizing and delivering primary care services. In 2019, 98 percent of the municipalities had adopted the Family Health Strategy model. There were more than 43,000 family health teams and at least 26,000 oral health teams providing care to more than 133 million people (64% of the population).15

Most municipalities hire family health team members and set their salaries, resulting in wide wage variations across the country.

The expansion of primary care has increased outpatient doctor visits, leading to a reduction in hospital admissions.16 In SUS, Brazilians have direct access to primary care and emergency services, but referrals are required for accessing outpatient specialties and hospitals.

The poor quality of services in primary care is a challenge. To address the problem, the federal government introduced a pay-for-performance program for family health teams in 2011.

In the private insurance sector, health plans have begun to offer access to family doctors with no copayment as an alternative to specialist visits — a policy fostered by the National Agency of Supplementary Health.

Outpatient specialist care: States or municipalities oversee the provision of specialty care, including service delivery and provider payment. Outpatient specialty care is usually organized in association with hospital care.

Facilities vary in scope and organization, ranging from stand-alone specialized ambulatory care facilities to polyclinics with several ambulatory specialities. Outpatient services can be delivered by public entities (municipal, state, or federal) or private facilities (nonprofit or for-profit). Most outpatient facilities are in the private sector.

SUS allows access to outpatient specialists after a hospital discharge. Otherwise, a referral from a primary care physician is required.

The federal government reimburses states or municipalities according to the volume of specialist services provided. States and municipalities pay for specialist services predominantly on a fee-for-service basis. The fees follow the national list of SUS procedures (tabela SUS), which are usually well below actual costs. For example, the fee schedule for a specialist consultation is less than BRL 10 (USD 2.33).

Specialists who work in the public sector have the freedom to undertake private work and see private patients.

Innovative initiatives are underway to change the outpatient specialist model of care and integrate specialist services into health networks.17 For instance, public–private partnerships are being considered.18 However, integration has been challenging, and access to specialist services is a major bottleneck in SUS. The unnecessary referral and retention of patients by specialists results in long queues for individuals in genuine need of specialized care. Unmet demand and delays in diagnosis are also common problems.

Specialist outpatient services are free of charge in SUS, but capacity shortages have constrained access to specialist services in the public sector and encouraged the growth of a substantial private market in outpatient specialist care.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Since primary and specialty outpatient care is free to Brazilians under SUS, patients do not have to make any direct payments to providers.

After-hours care: After-hours care is usually provided by hospitals, as well as by emergency care units. Created in 2008 to address the lack of hospital beds, these units are an important component of the emergency care network, with each unit providing 24/7 services to cover a population of 50,000 to 300,000 people.19

Although emergency care units are supposed to be integrated with primary care services, ambulance services, and hospital care in health regions, coordination between these services is weak. In 2019, there were 1,072 emergency units in 868 municipalities.20 Doctors or nurses in the emergency care units usually also work in hospitals or ambulances, and less commonly in primary care.

The Ministry of Health has created monetary incentives to ensure adequate emergency care. In addition to helping municipalities invest in new emergency care units, the government helps cover expenses for established units.

Hospitals: Although the federal government contributes to the financing and delivery of services by federal hospitals, the contracting and reimbursement of hospital services is the responsibility of either the state or the municipal government.

In 2015, there were 6,154 general and specialized hospitals in Brazil, with 443,257 beds, of which 71 percent were in SUS. Of the total number of hospitals, 38 percent were public and 62 percent private. Among the public hospitals, 4 percent were federal, 25 percent were owned by states, and 70 percent were owned by municipalities. Among private hospitals, 38 percent were nonprofit and 63 percent were for-profit.21

While the majority of hospitals (52%) are located in municipalities, most of these are small, with fewer than 50 beds, and have low levels of efficiency and effectiveness. Federal and state public hospitals are usually larger in size, have higher occupancy rates, and provide higher-complexity procedures.

Inpatient care is financed using two mechanisms. First, the federal government estimates the number and profile of hospital admissions for each municipality or state on the basis of population needs, available infrastructure, and historical trends. Predetermined payments are set for different diagnoses. For each diagnosis, there is a package of procedures and an expected length of hospitalization. Based on those estimates, the Ministry of Health transfers funds to the state or municipality, which in turn reimburses the hospitals on a fee-for-service basis.

There is also a second payment system for high-complexity procedures. Every establishment that delivers highly complex procedures, such as chemotherapy, and distributes high-cost drugs is reimbursed under this system. The Ministry of Health directly reimburses municipalities or states according to the volume of complex services delivered. The state or municipality then pays the facilities providing the services.

The fees under both payment systems follow the national list of SUS procedures, which is not updated regularly. As a result, relative prices are distorted. To compensate in part for this deficit, the Ministry of Health has implemented performance-based incentive payments for state- or municipality-owned hospitals to achieve specific goals, including the integration of hospitals with other health care providers.

In public hospitals, health professionals are typically contracted by the government and paid fixed monthly salaries. More recently, some states and municipalities have begun contracting with private organizations and/or entered into public–private partnerships to manage hospitals. In 2015, there were 51 organizations contracted to provide inpatient care.

Mental health care: In 2001, Brazil began shifting mental health care from hospitals and hospice-based inpatient settings to community- and home-based outpatient care.22 Psychosocial Care Centers form the core of these mental health services. The centers have multiprofessional teams that provide care for people with behavioral health issues, including substance use disorder. They offer clinical care and psychosocial rehabilitation, and aim to avoid hospitalization and emphasize social inclusion. In 2019, there were just over 3,000 centers in some 2,000 municipalities. The centers are being reorganized as part of mental health networks.23

Mental health networks also include:

- residential therapeutic services for patients who have previously received inpatient care and do not have any relatives who can take care of them

- host units, which are short-term residential services offering continuous care mainly for vulnerable populations

- mental health teams that are integrated with family health teams at primary care centers, emergency care units, and hospitals.

Brazil also provides subsidies to some individuals with mental disorders during their post-discharge rehabilitation period. Individuals who receive inpatient care for more than two years without interruption are eligible to receive a cash transfer of approximately BRL 412 (USD 96) per month for one year, which can be renewed if necessary.24

Long-term care and social supports: In 2015, 11,227 hospital beds (2.5% of total) were classified as beds for chronic patients. Of those, 9,439 (84%) were in SUS; the rest were in the private sector.18 Since 2012, the Ministry of Health has been financing long-stay beds, characterized as extended-care units, for clinically stable patients receiving rehabilitation.

SUS also offers home care services, according to a patient’s health needs. Less-complex patients can receive visits by the family health team. Cases of higher complexity, requiring more intensive health care, can be seen by multiprofessional home care teams.

In 2019, there were 831 home care teams in 241 municipalities across the country.18 Each team can cover 30 to 60 patients.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

Over the years, several initiatives were developed within SUS to better evaluate health system performance, protect patients, and improve quality of care.

In 2012, the Ministry of Health launched SUS Performance Index, which tracks indicators related to access, effectiveness, equity, and other improvement goals. However, political and policy changes have hampered the use of these evaluations for improving quality of care.

In 2011, the Ministry of Health created a national program for improving access and quality in primary care. Although voluntary, the program included nearly 39,000 family health teams. As a financial incentive to improve quality, family health teams receive additional payments based on a facility evaluation, performance on health indicators, and interviews with health care professionals, municipal managers, and service users.25

In the hospital sector, the Brazilian Accreditation System was created in the late 1990s with the aim of promoting the improvement of quality of care. The National Accreditation Organization leads hospital accreditation. According to a 2009 survey, many accredited hospitals were private, had more than 150 beds, and were in Brazil’s southeast.

In 2013, the Ministry of Health established the National Patient Safety Program, which follows the World Alliance for Patient Safety’s guidelines. Patient-safety centers have been established in public and private hospital services, and it is mandatory to report adverse events, including inpatient falls and misapplications of medication.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

Democratic progress in Brazil has enabled the development of national policies to ensure human rights and universal access for vulnerable groups.26 The National Human Rights Plan defends civil rights, protects social groups that have suffered historical inequities, and guarantees social rights in the context of economic inequalities.

Health policies have been implemented to improve equity and reduce disparities for black Brazilians; Romany and descendants of escaped slaves (quilombolas); lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender groups; the homeless; and people living in rural areas and riverine communities. Initiatives have included adding gender reassignment surgery to SUS coverage; adding information on color and race to SUS ID cards; giving attention to sickle cell anemia, which disproportionately affects black people; exempting gypsies from having to show proof of residence to qualify for SUS care; and recognizing the role of healers and midwives in health care.

In the Ministry of Health, the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health was created to coordinate and manage policies and programs related to the health of indigenous people. Priorities include observing traditional health practices and carrying out sanitation actions to ensure indigenous health. The Brazilian indigenous population encompasses nearly 820,000 people in close to 5,400 villages (12.6% of Brazilian territory).

The expansion of primary care has led to large improvements in access and in health outcomes.27 Primary care services have been developed locally to reduce disparities and address differential patterns of burden and need. Local solutions include mobile clinics for the homeless, floating health units in river communities, and indigenous health teams.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

Brazil has developed organizational frameworks for health care coordination across the regionalized health system, including the following:

- Regional regulatory centers coordinate patient referrals to outpatient specialized, hospital, and emergency services.

- Guidelines for organizing health care networks have been published by the Ministry of Health.

- Financial incentives, care guidelines, and care pathways encourage the coordination of mental health care, emergency care, maternal care, and care for people with disabilities, chronic diseases, and cancer.

- The telehealth program, established by the Ministry of Health, provides remote clinical care and support, reducing costs for patients and expanding the capabilities of family health teams.

However, integrated, coordinated care remains a major challenge, especially in the private sector, resulting in fragmentation, redundancy, and major gaps in health care.

What is the status of electronic health records?

Information technology is coordinated nationally by the Department of Informatics, which is linked to the Ministry of Health. However, states and municipalities use different information systems, leading to data integration challenges and making it difficult to implement a national integrated electronic health record (EHR).

Since the late 1990s, the Ministry of Health has developed policies and initiatives to implement a National Health Card with an individualized number for each person, to better monitor utilization and to optimize service provision.

Recently, the Ministry of Health launched e-SUS software intended to integrate the multiple information systems within SUS.

In 2017, 90 percent of health care providers in the public sector used computers and 77 percent had access to the Internet.28 In 2018, about 19,000 of the 42,600 primary care units used EHRs. Of these, 9,373 primary care units were using the Ministry of Health EHRs, and 9,790 had their own systems.

How are costs contained?

A 17 percent increase in the cost of medicines and medical supplies was observed between 2010 and 2014.29 Important efforts have been launched by the federal government to contain these costs, including more-pervasive regulation of new technologies, centralized purchasing of high-cost medicines, and public–private partnerships for the national production of strategic products through technology transfer. In 2012, the National Commission of Technologic Incorporation (CONITEC) was established. The CONITEC approves inclusion, exclusion, and approval guidelines for the use of new and existing health technologies. From 2012 through 2016, 69 health technologies were removed while 132 new health technologies were incorporated (62% of these were medicines and 38% were medical devices, diagnostic products, health products, and procedures).30 In 2018, 84 partnerships for technology transfer were initiated: 67 for medicines, 12 for equipment and medical materials, and five for vaccines, with an estimated savings of BRL 4.68 billion (USD 1.09 billion) in product purchases between 2011 and 2017.31

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

Brazil’s ongoing political and economic crisis has affected financing for all public policies and programs, including SUS.32 Long-term fiscal austerity policies were implemented in 2016 and followed by rationing measures. In 2017, around 1,200 ministerial directives that regulate transfers of federal resources were unified under a unique consolidation ordinance.33 In addition, the federal government has promoted the unification of SUS financing for primary care, complex health services, pharmaceutical care, and health surveillance and management. The goal is to reduce bureaucracy and increase flexibility in how municipalities use financial resources at local levels. Despite the benefits of these measures, there are concerns about underfinancing in strategic areas, such as primary care and health surveillance, due to the concentration of financial resources in specialized and hospital care.34

After a political shift in 2019, the new Brazilian government maintained its fiscal austerity policy and introduced other social, educational, and environment policies that may threaten health.35 Nevertheless, the Ministry of Health has proposed new policies to strengthen and expand access to primary care, including the creation of a new secretary dedicated to primary care. These policies aim to increase access to family health units; to delineate a new efficiency-based funding model and a model for the training and provisioning of physicians in remote areas; and to expand the use of electronic medical records.36