By Robin Gauld, University of Otago, New Zealand

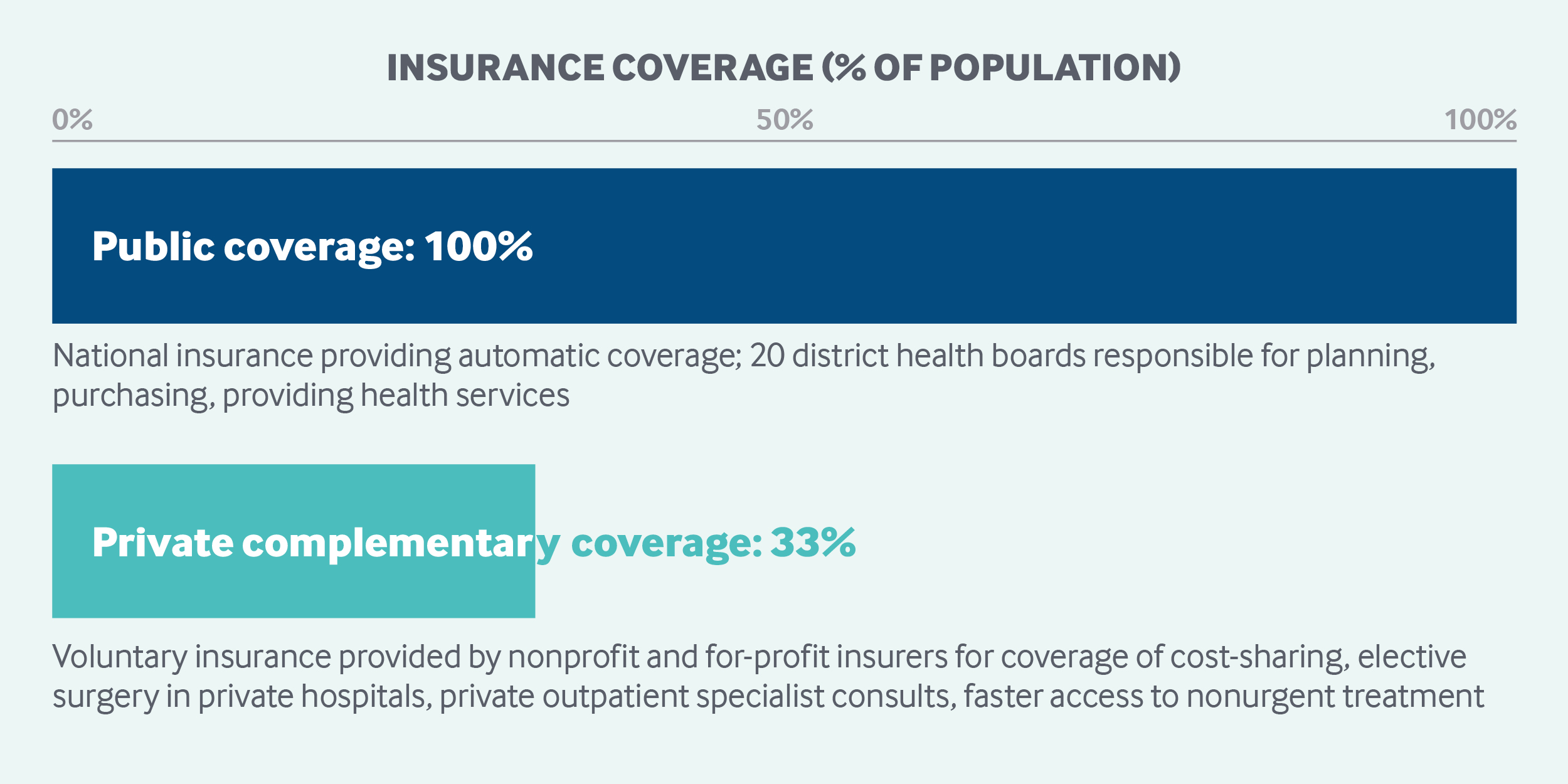

New Zealand has achieved universal health coverage through a mostly publicly funded, regionally administered delivery system. Services covered include inpatient, outpatient, mental health, and long-term care, as well as prescription drugs. General taxes finance most services. The national government sets an annual budget and benefit package. District health boards are charged with planning, purchasing, and providing health services at the local level. Patients owe copayments on some services and products, but no deductibles. Approximately one-third of the population has private insurance to help pay for noncovered services and copayments.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

Beginning with the 1938 Social Security Act, a consensus developed in New Zealand that government has a fundamental role in providing for the population’s health care needs. Not long after that law’s passage, the government achieved its goal of universal health coverage. No citizen can be denied treatment in public hospitals, and all citizens have insurance through government-funded, universally accessible health services. In practice, however, coverage varies by income, need, location, and type of service.

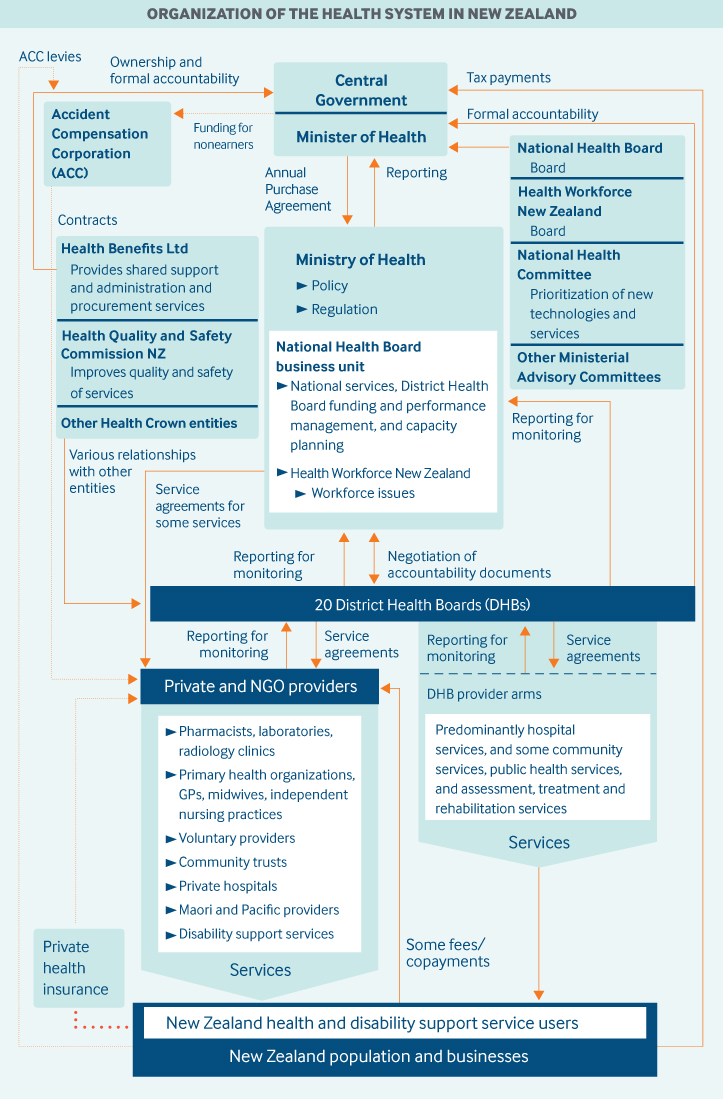

Role of government: The national government plays a central role in setting the health care policy agenda and service requirements and in determining the publicly funded annual health budget. The government dominates all aspects of health care as the primary funder and supplier of health care; it also sets regulations and monitors compliance.

The government sets an annual overall budget and benefit package, based largely on political priorities and health needs. It also sets national requirements for publicly funded services, to be implemented by 20 geographically defined district health boards.

Responsibility for planning, purchasing, and providing health services, as well as disability support for those over age 65, lies with the district health boards, each of which comprises seven locally elected members and up to four members appointed by the minister of health.1 These boards pursue government objectives, targets, and service requirements while operating government-owned hospitals and health centers, providing community services, and purchasing services from nongovernment and private providers.

Because New Zealand’s health system is primarily public, government-funded and government-appointed entities dominate governance structures. Some operate at arm’s length from the central government, such as the Health and Disability Commissioner, which champions consumers’ rights in the health sector. Others are “crown agents,” funded by government, with their own boards, and are required to follow government policy. Key national entities are:

- The Ministry of Health, which has overall responsibility for the health and disability system, acts as the minister of health’s principal adviser on health policy, and maintains a role as funder, monitor, purchaser, and regulator of health and disability services.

- The Technology and Digital Services business unit, within the Ministry of Health, is responsible for implementing the government’s Digital Health Strategy and other e-health initiatives.

- The Capital Investment Committee, which is a Ministry of Health subcommittee, advises on matters relating to capital investment in the public health sector, in line with the government’s service plans.

- Health Workforce New Zealand leads and supports health and disability workforce training and development.

- NZ Health Partnerships, owned and supported by New Zealand’s 20 district health boards, is tasked with helping the boards pursue bulk procurement of medical equipment, devices, and services.

- The Pharmaceutical Management Agency of New Zealand assesses the effectiveness of drugs, distributes prescribing guidelines, and determines the inclusion of drugs on the national formulary.

- The Health Quality and Safety Commission is working toward New Zealand’s version of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim: improved quality, safety, and experience of care; improved health and equity for all populations; and better value for public health system resources.

- The Health Promotion Agency develops and enables health-promoting policy, initiatives, and environments.

- The Health Research Council invests in a broad range of research on issues important to New Zealand.

Role of public health insurance: All permanent residents have access to a broad range of services that are largely publicly financed through allocations from pooled general taxes, which are collected at the national level. One exception is treatments related to accidents, which are covered by a no-fault accident compensation scheme. Nonresidents, including tourists and undocumented immigrants, are charged the full cost of services by public health care providers.

Total health spending was 9 percent of GDP in 2017.2 Public spending accounted for 78.68 percent of total spending.

Role of private health insurance: Private health insurance is offered by a variety of organizations, from nonprofits to for-profit companies, and accounts for about 5 percent of total health expenditures. It is used mostly to cover cost-sharing requirements, elective surgery in private hospitals, and private outpatient specialist consultations. Private coverage also can ensure faster access to nonurgent treatment. About one-third of the population has some form of private insurance, and it is purchased predominantly by individuals.

Services covered: The publicly funded system covers the following services:

- preventive care

- inpatient and outpatient hospital services

- primary care via private providers, except for certain services, such as optometry, adult dental services, orthodontics, and physiotherapy

- maternity services

- physical therapy

- durable medical equipment

- inpatient and outpatient prescription drugs included on the national formulary

- mental health care

- dental care for schoolchildren

- long-term care

- home help

- hospice care

- disability support services.

Rationing of services and prioritization are applied largely to nonurgent services and vary by district health board.

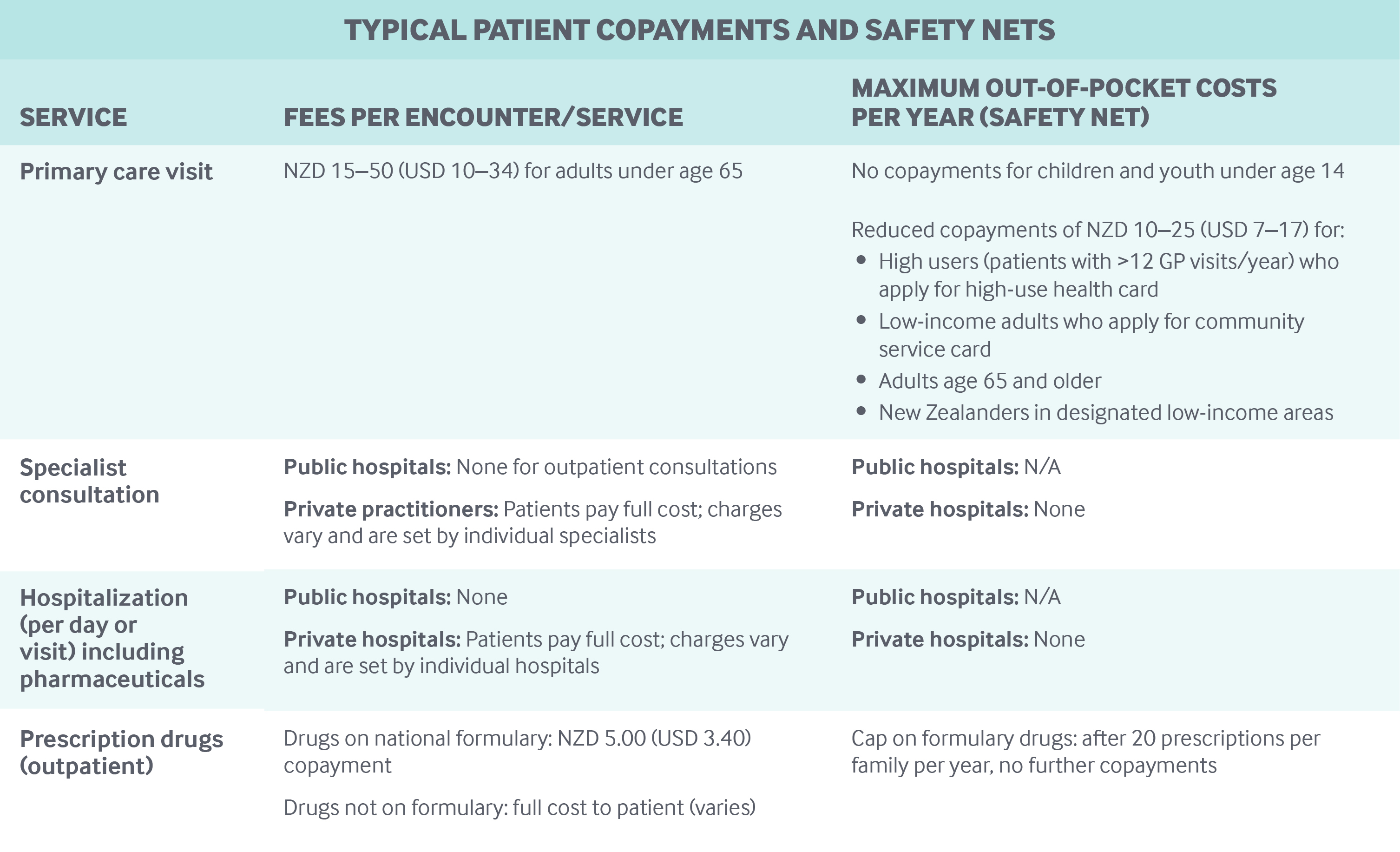

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: Out-of-pocket payments, including both cost-sharing and other costs paid directly by private households, accounted for approximately 12.6 percent of total health expenditures in 2015. The largest portion went to outpatient services.3

There are no deductibles in the public sector, although copayments are required for GP services and many nursing services provided in GP clinics. Immunizations and cancer screening services are usually free. The average adult copayment for a GP consultation varies significantly, from NZD 15 to NZD 50 (USD 10 to USD 34).4 In general, the government does not set limits on GP copayments, although the government has capped GP copayments at NZD 17.50 (USD 12.00) for one-third of New Zealanders residing in low-income areas.

For drugs prescribed by GPs and private specialists, copayments of NZD 5.00 (USD 3.40) are required for the first 20 prescriptions per family per year, after which there are no copayments.

Residents receive treatment free of charge in public hospitals, although there are some user charges, such as those for crutches and other aids supplied on discharge.

Safety nets: Primary care is mostly free for children ages 13 and under and is subsidized for the 98 percent of the population enrolled in networks of primary health organizations.

Patients who have had more than 12 GP visits in a year can apply for a high-use health card, which reduces the amount they owe in copayments. Low-income people can also lower their copayments by seeking a community services card.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Practicing physicians must be registered with the Medical Council of New Zealand. There is no limit to the number of registered physicians. However, the two medical schools, Otago and Auckland, both public, have a limited student intake, and specialist colleges also limit training places. Medical school limits are determined largely by the government, which is the primary funder of medical education.

Students pay a portion of costs, presently around NZD 15,000 (USD 10,100) per year, for the six-year medical degree. Students from rural areas are eligible for fee subsidies and reimbursements if they return to practice rurally. Rural practice remains on the New Zealand immigration department’s list of high-priority professions, meaning foreign doctors who opt to practice in rural areas of New Zealand are given preference when lodging immigration applications.

Primary care: GPs are usually independent and self-employed. Most belong to one of about 30 primary health organizations (PHOs), which are networks of providers.

About half of a GP’s income comes from capitated, government-determined national subsidies, paid through the primary health organizations. The capitation rate is periodically adjusted in negotiations with GPs and primary health organizations.

Patient copayments, set by individual GPs, and payments from the Accident Compensation Corporation account for a GP’s remaining compensation. In general, copayments are not regulated by any fee schedule; however, the government caps copayments for New Zealanders residing in low-income areas. A higher annual per-patient capitation rate is paid to GPs for these low-income patients. Primary health organizations receive additional per-capita funding to improve access (especially for low-income and vulnerable populations) and to aid in promoting health, coordinating care, and providing additional services for people with chronic conditions. In some cases, this support has led to the development of multidisciplinary care teams that may include specialists, such as nutritionists or podiatrists.

Primary health organizations also receive an incentive-type payment, up to 3 percent in additional funding, that can be shared with GPs who reach recommended targets for disease screening and follow-up, as well as for vaccinations.

GPs have an average income of NZD 180,000–200,000 (USD 122,000–135,000) per year. GPs who own their own clinics earn more.

The ratio of GPs to specialists is about 2:3. GPs act as gatekeepers to specialist care.

Patient registration is not mandatory, but GPs and primary health organizations must have a formally registered patient list to be eligible for government subsidies. Patients enroll with a GP of their choice; in smaller communities, choice is often limited.

An average of 3.48 GPs work together in each practice, assisted by practice nurses. Nurses are paid a salary by GPs and have a significant role in the management of long-term conditions like diabetes, incentivized by government funding for chronic care management.

Outpatient specialist care: Most specialists are employed by district health boards and receive a salary for working in a public hospital. The average public hospital specialist salary is around NZD 230,000 (USD 155,000).5 Thereby, specialists in public hospitals make about 1.1 to 1.3 times the income of GPs.

Specialists are also able to work privately in their own clinics or treat patients in private hospitals, where they are paid on a fee-for-service basis. The impact of this dual practice on the public sector remains under-researched.6

Many specialists are based in multispecialty clinics but work independently, renting their office from the clinic.

Private specialists are concentrated in larger urban centers and set their own fees, which vary considerably; insurance companies have little, if any, control over those fees. Insurers pay private specialists only up to a maximum set amount, meaning that patients pay any difference.

In public hospitals, patients generally have limited choice of a specialist.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: As noted above, GPs’ income is derived from government subsidies, payments from the Accident Compensation Corporation, and copayments from patients.

Some patients enrolled in private insurance may be eligible to file a claim to cover copayments.

Patients pay the full cost of private specialist visits up front, unless the service is funded by the Accident Compensation Corporation or by private insurance. In the latter case, patients may seek reimbursement from their insurer, or there may be no direct patient charge if a specialist or private hospital holds a contract with the insurer.

After-hours care: GPs are required in their funding contracts to provide after-hours care or to arrange for its provision, and they receive a separate government subsidy for doing so, which is a higher per-patient rate than the general capitation rate.

In rural areas and small towns, GPs work on call; in some of these areas, a nurse practitioner with prescribing rights may provide first-contact care.

In cities, GPs tend to provide after-hours service on a roster at purpose-built, privately owned clinics in which they are shareholders. These facilities employ their own support staff, such as nurses, but patients usually see a GP in the first instance. Patient charges at these clinics are higher than those for services during the day (except for most children under age 13, who can get free after-hours GP services). Consequently, some patients will visit a hospital emergency department instead of after-hours clinics or avoid after-hours services altogether.

A patient’s usual GP routinely receives information on after-hours encounters.

The public also has access to the 24-hour, seven-day-a-week phone-based “Healthline,” staffed by nurses who provide advice in response to general health questions. The “Plunketline” provides a similar service for child and parenting problems.

Hospitals: New Zealand has a mix of public and private hospitals, but public hospitals constitute the majority, providing all emergency and intensive care.

Public hospitals receive a budget from their owners, the district health boards, based on historic utilization patterns, population needs projections, and government goals in areas such as elective surgery. The budget includes the costs of health professionals and other staff, all of whom are salaried. Within a public hospital, the budget tends to be allocated to the various inpatient services using a case-mix funding system, although some services are funded regardless of case mix.

A proportion of district health board funding for elective surgery is held by the Ministry of Health, and payments are made on delivery of surgery.

Following a pay-for-performance-type scheme, payments can be withheld if a district health board does not meet elective targets.

Certain areas of funding, such as mental health, are “ring-fenced”; the district health board must spend the money on a specified range of services.

Private-hospital patients with complications are often admitted to public hospitals, in which case the costs are absorbed by the public sector. Public-hospital services are provided largely by consultant specialists, specialist registrars, and house surgeons.

Mental health care: Most people get access to mental health care through community-based primary mental health services, often through their GP, who will then coordinate any referred services. However, there are also school-based health services and community services provided by nongovernmental agencies, which are all publicly funded.

District health boards deliver a range of mental health services (including secondary services), such as forensic, acute inpatient, and community-based services. They also provide support to primary care providers and fund nongovernment providers of community-based services. Private provision is limited.

Long-term care and social supports: District health board funding for long-term care is based on a patient needs assessment, age, and means-testing. Services are funded for those over age 65 and those “close in age and interest” (e.g., people with early-onset dementia or a severe age-related physical disability).

Eligible individuals receive comprehensive services, including medical care and home care. Respite care is available for informal or family-member caregivers and, in some circumstances, ongoing financial support is provided. Residential facilities, mostly private, provide long-term care. District health boards also provide hospital- and community-based palliative care. Around 33 percent of people over age 65 who receive support live in some form of aged residential care, with the remainder receiving home-based services.

Disability support services for those under age 65 are purchased directly by the Ministry of Health. Some disabled people opt for individualized funding, which enables disabled people to directly manage their disability supports.

End-of-life care in New Zealand is provided in a range of settings, including hospitals, a network of hospices, aged residential care, and the individual’s home. District health boards either fully fund or contribute to these settings, according to population needs. Hospices also rely on fundraising for support.

Long-term care subsidies for older people are means-tested. Individuals with assets over a given national threshold pay the cost of their care up to a maximum contribution. Those with assets under the allowable threshold contribute all their income, except for a small personal allowance. District health funds cover the difference between a person’s payments and the contract price for residential care. For people in their own homes, household management (e.g., cleaning), which accounts for less than one-third of home support funding, is income-tested. Personal care (e.g., showering) is provided free of charge. Home care services are all provided by nongovernment agencies. Some district health boards have experimented with providing personal budgets to home support recipients to spend on selected approved services, but mostly home care services are directly funded by district health funds.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

The Health and Disability Commissioner, which serves as a national patient advocate, investigates patients’ complaints, reports directly to New Zealand’s parliament, and has been active in promoting quality and patient safety. A culture of openness and transparency is supported by New Zealand’s no-fault medical malpractice laws and accident compensation system.

District health boards are held formally accountable to the government for delivering efficient, high-quality care in hospitals, as measured by the achievement of targets across a range of indicators. These include six health targets, published quarterly, that aim to stimulate competition among district health boards. In addition, district performance on waiting times, access to primary care, and mental health outcomes is publicly disclosed. Also publicly reported are performance data on primary health organizations, including screening rates for chronic disease. Data on individual doctors’ performance, however, are not routinely made available. As noted above, primary health organizations and GPs receive performance payments for achieving various targets. There are currently no publicly available data on nursing home or home care agency performance.

District health boards and individual GP clinics and networks run various chronic disease management programs. There are national registries for some diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

Since 2014, public hospitals have been required to conduct patient experience surveys of randomly selected patients. The Health Quality and Safety Commission publishes the findings.

Certification by the Ministry of Health is mandatory for hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted-living facilities. All practicing health professionals must be certified annually by the relevant registration authority (e.g., for doctors, the Medical Council of New Zealand), which has ongoing responsibility for ensuring professional standards and providing accreditation. Registration authorities supervise individual professionals where appropriate.

The Ministry of Health is also working on quality improvement in district health boards. Most boards have implemented clinical governance, which means that management and health professionals have assumed joint accountability for quality, patient safety, and financial performance.7

The Health Quality and Safety Commission aims to increase the focus on quality and to coordinate district health board activities, such as those aimed at improving the patient journey, managing medications more safely, reducing rates of health care–associated infection, and standardizing national incident reporting. Other initiatives include the following:

- The ongoing development of the Atlas of Healthcare Variation, an online tool aimed at highlighting variations in the provision and use of services by geographic area.

- A series of standard quality and safety indicators for district health boards based on routinely collected data.

- A program for consumer involvement in service design.

- Advice for district health boards on how to prepare annual “Quality Accounts,” required since 2012–2013; these Quality Accounts report on how a district health board approaches quality improvement, including descriptions of key initiatives and their results.

- A national patient safety campaign launched in 2013, called “Open for Better Care,” which is focused on reducing harm associated with falls, surgery, health care–associated infections, and medications. Since 2015, the campaign has collated routine data in an annual report aimed at providing a window on the quality of New Zealand health care.8

Lastly, New Zealand is a partner in the global Choosing Wisely initiative, aimed at reducing low-value and potentially harmful care.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

Health disparities are a concern in New Zealand. Maori and Pacific Island people have shorter life expectancies than other New Zealanders (by seven and five years, respectively) and experience greater difficulty in gaining access to health services. Reducing disparities is a policy priority. Data describing disparities are routinely collected and publicly reported at both the national and the district level.9 A full range of data are collected and reported, including socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and proximity to services.

The post-2008 government has focused on specific initiatives such as “Whānau Ora,” a policy designed to integrate health and social services. The aim has been to develop coordinated, multiagency approaches to service provision and to foster joint responsibility for outcomes. The government now requires district health boards to report on Māori health plans in their statutory reporting, and to consult with Māori on their annual plans.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

District-level alliances (partnerships between district health boards and primary health organizations) are driving stronger health system integration, although performance varies across regions. The alliances have multiple cross-sector members including, but not limited to, primary care, pharmacies, ambulance services, district nursing, allied health, local government, and Maori providers. District alliances are developing services based on locality-specific needs. Some alliances have begun to form partnerships with local social agencies.10

The primary care sector is exploring how to best improve and enhance primary care to meet future demand. The “health care home” model is being implemented in several districts, with support and resourcing shared between district health boards and primary health organizations.

While district health boards are held accountable for driving integration through their annual plans, variability still exists. There is an ongoing effort to drive improvement by other means, including new funding models and contracting for outcomes. For instance, four system-level performance measures were implemented in 2016. The success of these measures is dependent on the contributions of individual providers or organizations.

What is the status of electronic health records?

The ability to access and share accurate clinical information is central to the New Zealand Health Strategy, which provides high-level direction for the country’s health system.11

In 2015, the Ministry of Health announced, and has responsibility for, the Digital Health Work Programme 2020. The program aims to ensure appropriate access to health and wellness information facilitated by a single electronic health record. The electronic record will collect and present existing core health information in a single view, accessible by consumers and clinicians. Data will also be able to be shared with social-sector professionals.

Current levels of interoperability between health information systems are limited. However, the structured electronic transfer of information is increasing. Primary care is most advanced. Across the country, primary care providers can transfer patients’ records securely between practices, send electronic referrals, and receive electronic hospital discharge summaries. In one of New Zealand’s four regions, providers in community, hospital, and specialist settings can also access a shared view of clinical information. The other three regions are working on enabling information-sharing in these settings. Implementation of electronic prescribing is under way in primary care and in hospitals. The use of telehealth to deliver services remotely is also increasing.

A recent survey found that 509 of 992 general practices have implemented provider portals, giving after-hours facilities and some hospital emergency departments access to primary care information.12 The Health Information Standards Organisation promotes the development and use of standards to ensure interoperability between systems, and a national standard for clinical terminology (the Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine — Clinical Terms) has been endorsed. Every person who uses health and disability support services has a unique national health number, facilitating the process of building interoperable systems.

Over half of primary care practices have implemented a patient access portal, and approximately 473,000 patients have registered. The portal gives patients access to their medical records and test results and allows them to book appointments with GPs, order prescription refills, and email a GP. The portal supports the New Zealand Health Strategy’s goals of moving services closer to home and enabling health care consumers to actively manage their own health and engage more conveniently with the health system.

How are costs contained?

The financial sustainability of publicly funded health care is a top government priority. To support this goal, government has implemented a range of measures, including four-year planning within district health boards to align expenditures with priorities and improve regional collaboration to drive efficiencies. All new proposals must demonstrate their fit with the four-year plan and the strategic direction of the health sector.

Cost control in district health boards is closely monitored by the Ministry of Health. In the early 2000s, the adoption of new service delivery models and other efforts to improve efficiencies helped to decrease district health board deficits. However, budgets have been under constant pressure: a growing population characterized by increasing numbers of older and higher-acuity patients has led to rising deficits since 2015. Because public hospitals are essentially free of charge and funding allocations are fixed, there is no mechanism to shift increasing costs to patients or generate additional income.

The Pharmaceutical Management Agency, which is New Zealand’s centralized drug purchasing entity, considers cost and savings as one criterion for including a drug on the national formulary. (Other factors are health benefit, need, and suitability.) The agency also uses mechanisms such as reference pricing to set prices for publicly subsidized drugs dispensed through community pharmacies and hospitals.13 When patients prefer an unsubsidized drug, they must pay the full cost. Such strategies have helped drive down pharmaceutical costs and kept New Zealand’s drug expenditures per capita among the lowest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).14

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

The updated New Zealand Health Strategy, launched in 2016, consists of two parts: the Future Direction15 and the Roadmap of Actions 2016.16 The former lays out some of the challenges and opportunities the health system faces and describes the desired future, including the underpinning culture and values. In addition, it identifies five strategic themes for driving change:

- improving patient literacy and empowerment

- emphasizing prevention, early intervention, and community care

- improving system performance

- delivering integrated and collaborative health care delivery

- pursuing technological innovation.

The Roadmap of Actions 2016 identifies 27 action areas to implement by 2021. These actions, organized under the five themes listed above, will ultimately contribute to the stated goal that “all New Zealanders live well, stay well, get well, in a system that is people-powered, provides services closer to home, is designed for value and high performance, and works as one team.”17

The 2017 election produced a new coalition government, introducing some new priorities. These include the following:

- a renewed focus on reducing inequalities

- reducing care access barriers and unmet needs

- improving primary care

- the launch of an inquiry into mental health and addictions.

The new government has also pledged an additional NZD 8.0 billion (USD 5.4 billion) in health funding over the next four years. In May 2018, the new government announced a wide-ranging review of the health system. Recommendations on how to improve the system’s structure are due by early 2020. Particular attention is being given to primary and community care and the capacity to deliver on equity-related goals.

The author would like to acknowledge the New Zealand Ministry of Health for its comments and for providing updated information for this profile.