Ingrid Sperre Saunes, Senior Adviser, Norwegian Institute of Public Health

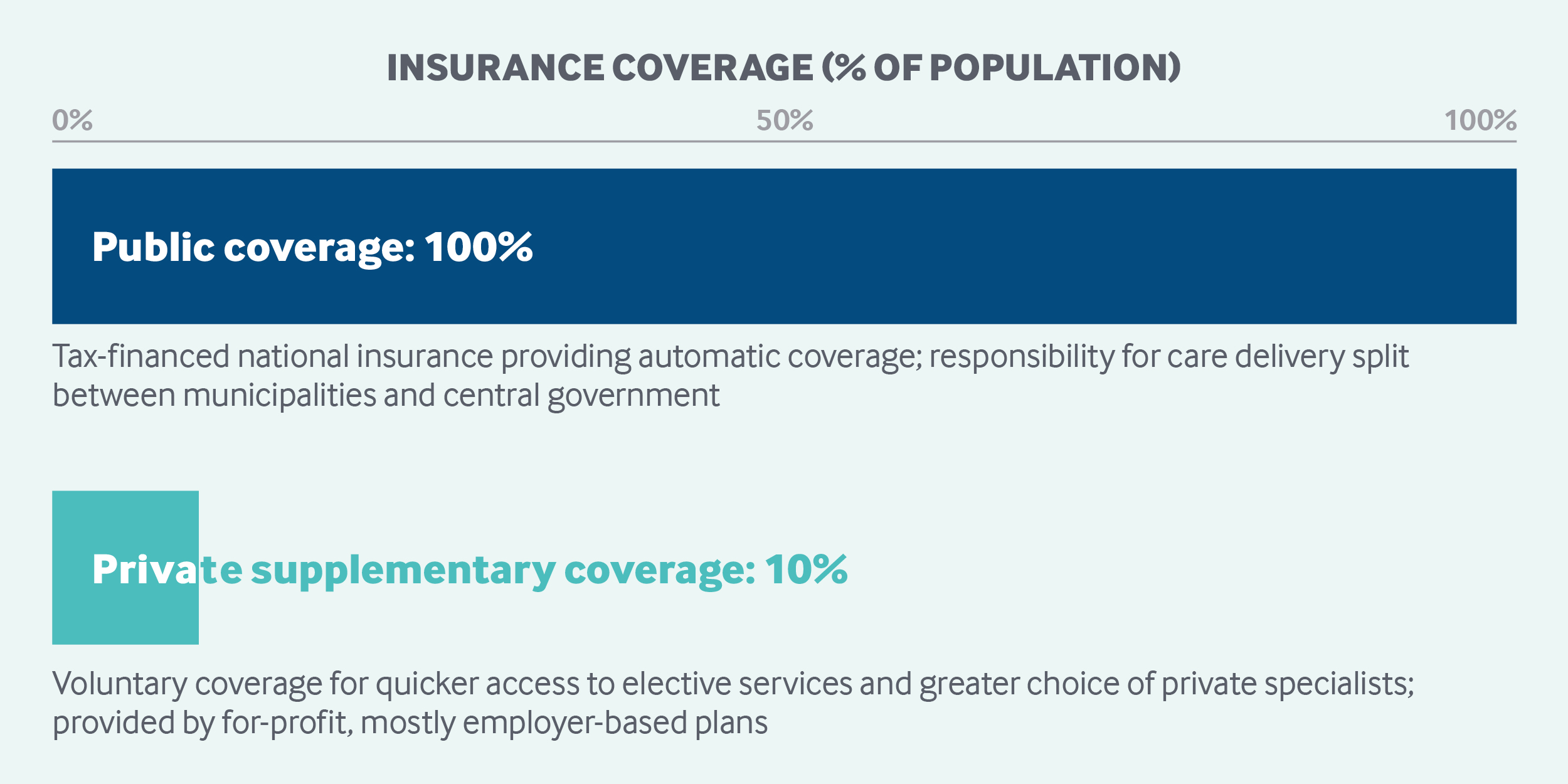

Norway has universal health coverage, funded primarily by general taxes and by payroll contributions shared by employers and employees. Enrollment is automatic. Services covered include primary, ambulatory, mental health, and hospital care, as well as select outpatient prescription drugs. Patients make copayments for some services and products, with caps on out-of-pocket contributions for most services. Municipalities organize primary health care, while the national government is responsible for specialty care, including hospital services, through the state-owned regional health authorities. About 10 percent of the population has private insurance, mainly to gain quicker access to and greater choice of private providers.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

Norway has universal health and social insurance coverage, known as the National Insurance Scheme (NIS), or Folketrygd. It is currently regulated by the 1997 National Insurance Act and the 1999 Patient Rights Act.

The establishment of universal coverage has a long history in Norway. Political and social movements began advocating for universal social and health care insurance around 1900. The Act of Health Insurance, covering employees as well as their families, came into force in 1909. Membership was mandatory for low-income employees; others could opt in. The coverage was twofold: health care and guaranteed basic income in case of income loss due to ill health. In 1956, the system was converted into a universal and mandatory right for all citizens.

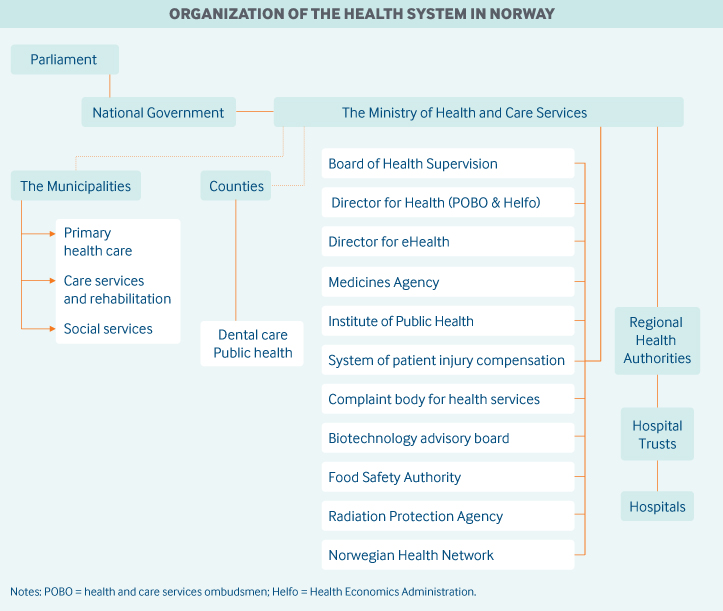

Role of government: The national government is responsible for providing health care in accordance with the goal of equal access to care regardless of social or economic status or geographical location.1 It is also responsible for regulating, funding, and overseeing the provision of care. However, responsibility for the administration of care is shared with the municipalities, through the municipal councils.

Primary, preventive, and nursing care are organized locally. In addition, the municipalities, often in cooperation with the counties, decide on public health initiatives or campaigns to promote healthy lifestyles and reduce social health disparities. All municipalities must statutorily guarantee access to publicly funded physiotherapy services.

Municipalities are also responsible for providing long-term care, which is not included in universal health insurance.

The national government is responsible for hospital and specialty care, which are handled at a local level through four Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) The RHAs have the overall responsibility for implementing national health policy through planning, organizing, managing, and coordinating activities with the hospital and pharmacy trusts in their region.

The following agencies have important roles in Norway’s health care system.

- The National Board of Health Supervision is the central supervisory authority over health care.

- The Ministry of Health and Care Services translates political decisions into practice through legislation, economic measures, and documents that instruct underlying agencies.

- The Directorate of Health is responsible for implementing national health policy through targeted activities across services, sectors, and administrative levels, including the development of national clinical guidelines and licensing of health personnel.

- The Norwegian Health Economics Administration (Helfo) is responsible for making direct payments to providers and setting reimbursement levels.

- The Health and Social Services Ombudsmen in each county acts as a patient advocacy agency, assisting patients and clients to get the help or treatment they need.

- The eHealth Directorate is responsible for leading the development and application of health information technology and providing information about the performance of health services.

- The Norwegian Medicines Agency (Statens legemiddelverk, or NOMA) safeguards public and animal health by ensuring the efficacy, quality, and safety of medicines and by administering and enforcing medical device regulations.

- The Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) conducts research and surveillance related to the population’s health, including disease prevalence and infection control.

Role of public health insurance: Health expenditures represented 10.5 percent of GDP in 2016, or NOK 68,065 (USD 6,647) per person,2 according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Public sources account for most health expenditures in Norway, at 85 percent.

Health coverage is automatic for all residents and has two main funding sources: the general tax system and household out-of-pocket payments. The split between public and private funding has been stable for the past 20 years. Public sources consist of transfers from national and municipal taxes, representing 76 percent, and contributions from state and payroll taxes, representing 11 percent. Taxation rates are set in the national budget. In 2018, the employee rate was 8.2 percent and the employer rate varied between 5.1 percent and 14.1 percent.3

Government funding for municipalities is generally not earmarked, and budgets are set locally by the municipality councils. The main sources of income for municipalities are taxes (55%) and block grants from the government (45%). Fifty-two percent of municipal budgets is devoted to health care and social services.

The NIS accounted for 35 percent of the national budget in 2015, or NOK 420 billion (USD 41.2 billion). The distribution of funding was 31 percent from enrollees, 41 percent from employers, and 28 percent from the state and others.4

In addition to health coverage, the NIS finances public retirement funds, sick leave payments, and additional health costs for some patient groups.

Through common agreements, European Union (EU) residents have the same access to health services in Norway as in their home country. Visitors from most other countries are charged in full. Undocumented adult immigrants have access only to emergency acute care, while undocumented children receive the same care as citizens.

Role of private health insurance: For-profit insurers offer quicker access to outpatient services and greater choice of private providers. Private insurance policies cover fewer than 5 percent of elective services; it does not cover acute-care services. In 2016, about 10 percent of the population (500,000) had some private insurance. About 90 percent of these policies are paid for by an employer.5 Revenue from private voluntary health insurance remains negligible.

Services covered: Parliament determines what is covered, although there is no defined benefit package except for new and costly treatments and technologies.

In practice, national health care covers the following:

- primary and ambulatory care

- hospital care

- mental health treatment

- rehabilitation

- outpatient prescription drugs, if included on the national formulary

- preventive services

- maternity care from a midwife at a Maternity and Child Health Care Centre or from a general practitioner (GP)

- home-based care and palliative care

- medical equipment on a needs basis

- dental care for children up to age 18, people with chronic diseases, nursing home residents, and other prioritized groups, as well as partial dental coverage for young adults ages 19 and 20 and dental braces for children.

Regular glasses and contact lenses are not covered unless the vision is very limited. Cosmetic surgery is not covered.

Again, long-term care is not a part of universal health insurance and is covered by the municipalities and patient copayments (see “ Long-term care and social supports,” below).

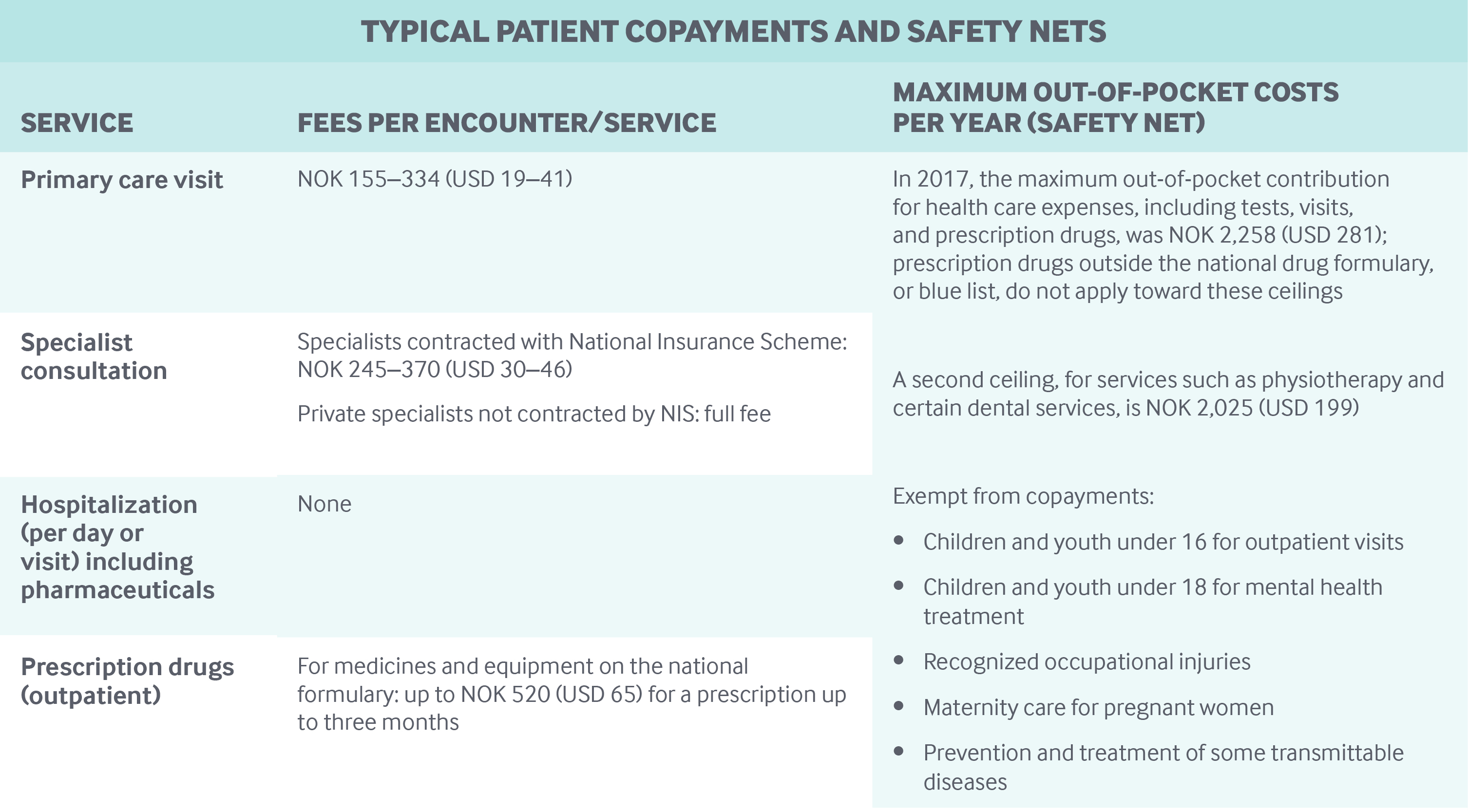

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: Out-of-pocket payments account for the biggest part of private revenues and made up approximately 14.3 percent of health expenditures in 2015. Patients owe copayments for most types of outpatient care (see table).

Safety nets: The major safety-net mechanisms are annual caps, set by Parliament, for out-of-pocket expenditures, above which all user fees are waived (see table).

Other safety net mechanisms include the following.

- Residents eligible for minimum retirement or disability pensions, which amount to about NOK 167,169 (USD 16,389) per year, receive free essential drugs and nursing care.

- Individuals with certain communicable diseases, including HIV/AIDS, and patients with work-related injuries receive free medical treatment for their conditions.

- Taxpayers with high health expenses, above NOK 9,180 (USD 900), due to permanent illness receive a tax deduction.

- Patients who regularly incur additional expenses because of permanent illness, injury, or disability may apply for an additional cash transfer known as basic benefits (NOK 678–3,383 [USD 66–332] per month).

- Individuals whose functional capacity is significantly and permanently (i.e., for more than two years) impaired owing to injury, bodily defect, or other health issues are entitled to receive financial support for assistive devices, such as wheelchairs, under NIS.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Medical education programs are offered at four public universities. The yearly educational capacity is set at 600 students, and the tuition fees are about NOK 1,200 (USD 118).

In 2015, 38 percent of physicians were trained outside Norway; however, nearly 50 percent of foreign-trained doctors are Norwegian-born. Many Norwegian students choose to study in EU countries and return to Norway to practice medicine.

Statistics Norway and the Directorate of Health have a shared responsibility for monitoring the health care workforce in Norway. Municipalities are primarily responsible for ensuring GP supply, but may apply to the Directorate of Health for extra funding to ensure an adequate supply of physicians. Funding may support the establishment of new practices and facilitate continuing medical education or other skill-building.

Primary care: The municipalities are responsible for providing primary care to their populations. Registered residents have the right to go to a GP of their choosing, assuming the physician has capacity to take on additional patients. The average patient panel size for a GP was 1,120 in 2016.6

Municipalities contract with individual GPs, who are mostly self-employed; only 6 percent are salaried municipal employees. Average annual earnings are NOK 804,000 (USD 78,824).7 GP practices typically comprise one to six physicians and employ nurses, lab technicians, and secretaries. GP networks that enable sharing of resources are not common.

GPs function as gatekeepers. A GP referral is required for coverage of specialist treatment.

GPs receive 35 percent of their income from the municipalities, 35 percent on a fee-for-service basis from the central government through Helfo, and 30 percent from out-of-pocket payments from patients. GP financing is determined nationally through negotiations between the Norwegian Medical Association and the central government (represented by the Ministry of Health and Care Services, Ministry of Finance, and Directorate of Health), as well as representatives from the RHAs and the Association of Municipalities. The fee-for-service scheme also includes specific, relatively small fees available for: medication reconciliation, care coordination, and the development of care plans for patients with complex needs.

Outpatient specialist care: Public hospitals and self-employed specialists provide specialty care. There are 2.8 specialists in hospitals or ambulatory care for every practicing primary care physician.8

Hospital-based specialists are salaried; the average salary for hospital specialists is an estimated NOK 1,032,000 (USD 101,176). Private-practice specialists may or may not contract with an RHA to be reimbursed under the NIS. RHA-contracted specialists are paid annual lump sums, based on the type of practice and number of patients, which account for 35 percent of their reimbursement. These specialists also receive fee-for-service payments (35% of payment) and copayments (30% of payment).

The annual lump sum and the out-of-pocket fees are set by the central government, and the fee-for-service payment scheme is negotiated between the government and the Norwegian Medical Association. The Ministry of Health and Care Services sets the RHAs’ budgets and issues an annual document instructing the RHAs on health care goals and priorities. Specialists with an RHA contract can charge patients only the nationally set out-of-pocket fee.

GPs and specialists who do not receive public financing are neither regulated nor subject to the out-of-pocket expenditure caps.

In principle, patients can choose their own specialists; in practice, however, specialist availability varies by geographic location. In densely populated areas, private multidisciplinary physician clinics have emerged in the last few years and seem to be increasing in number. Hospital-employed specialists cannot see private patients at the hospital, but may practice privately after hours.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Patients make copayments directly to care providers during their visits. The process is fully electronic and automated, alerting the patient and provider if the annual safety net ceiling has been reached.

After-hours care: The municipalities are responsible for arranging after-hours emergency primary care. Contracts with GPs include a requirement to provide after-hours emergency services on rotation. The municipalities pay the GPs a fee and provide offices, equipment, and assistance. Additional payments are provided through the national fee-for-service system and out-of-pocket payments from patients.

Some cities have walk-in centers where nurses triage patients and answer calls, with several physicians seeing patients throughout the day and night. In smaller municipalities, patients call an after-hours phone number and speak with a nurse, who calls the GP if the patient needs to be seen either at home or at the center. In larger cities, there are a few private after-hours clinics where patients pay in full. A national medical helpline guides patients on where to seek assistance.

Information about after-hours visits is not consistently shared with patients’ regular GPs.

Hospitals: Acute-care hospital services are the responsibility of the RHAs. Most hospital care is provided through Norway’s 20 public hospital trusts, which are state-owned and -governed as publicly owned corporations. In 2017, the public hospital trusts had 11,000 beds and accounted for 94 percent of all hospital stays, with 760,000 overnight stays.

Not-for-profit private hospitals, which can have tender agreements with RHAs, accounted for 5 percent of overnight hospital stays in 2017. The for-profit hospital sector, which is small, covered 6.5 percent of daytime stays, mostly outpatient surgeries.9 For-profit hospitals do not offer acute care or a full range of services. Some services in private hospitals may receive public funding, but the proportion varies, from almost none to 85 percent. Public funding of hospital care averages 85 percent.

Patients need a referral to acute-care services from a GP. However, in specific cases (e.g., accidents, suspected heart attack), patients can be taken directly to the hospital via ambulance. Patients are free to choose a hospital for elective services, but not for emergency care. All municipalities must provide intermediate-care units for patients who need pre- or post-hospital services for a limited time (<72 hours).

The RHAs are free to decide how hospitals are paid, and all four have chosen a diagnosis-related group (DRG) funding mechanism. Most services, including hospital administration, are included in DRG payments. One exception is somatic services, which are financed in part (50%) by block grants. Financing of hospital-initiated pharmaceutical care is the responsibility of the RHAs.

All hospital personnel are salaried, including doctors.

Mental health care: Mental health care is provided in municipalities by GPs, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and social care workers. Many municipalities have multidisciplinary mental health outreach teams.

Psychological care for children under the age of 18 is fully covered. Preventive services for mental health are directed toward children and adolescents through the school system.

For specialized care, GPs may refer patients either to private psychologists and psychiatrists or to community mental health centers, which provide acute-care services (inpatient, outpatient, and day care) and rehabilitation services while also supervising and supporting primary care. These centers are dispersed throughout the country and often include psychiatric outreach teams.

More advanced specialized services are provided in the inpatient psychiatric wards of general hospitals or in mental health hospitals. Hospital inpatient treatment is provided free of charge, and outpatient services are subject to the same cost-sharing as other ambulatory visits. Psychiatric services in hospitals and community mental health centers are funded in full (100%) by block grants through the RHAs.

Private mental hospitals account for about 12 percent of mental health care, including services for eating disorders, nursing home care for older psychiatric patients, and some psychiatrist and psychologist outpatient practices, mostly contracted by the RHAs. The role of private treatment centers for addiction (mainly to drugs and alcohol) is prominent and funded mostly through contracts with RHAs. In general, treatment for drug dependence is delivered by specialized treatment units, while GPs are involved in opioid substitution treatment.10

Long-term care and social supports: The municipalities are responsible for providing long-term care and may contract with private providers.

The majority of long-term care recipients (70%) receive care at home, while 10 percent live in sheltered or assisted housing facilities, which are independent housing arrangements in between home and institutional care. About 20 percent of recipients live in an institution or a home with personnel available 24 hours a day.11 Twenty-five percent of patients with extensive needs for assistance live in their own home.

Most nursing homes are owned and funded by municipalities; only 10 percent of all long-term care beds are in private nursing homes.12 Very few patients pay individually for full-time private nursing home care.

Service eligibility is needs-based, determined by municipal criteria in cooperation with GPs. Home-based and institutional care for older or disabled people requires means-testing; cost-sharing is high, up to 85 percent of personal income.

End-of-life care for terminal patients is often provided in specific wards within dedicated nursing homes. There are few designated hospice facilities.

There is a system in place for informal caregivers to apply for financial support from the municipalities. In 2017, 10,099 caregivers were granted such support,13 averaging around 10 hours per week. In addition, caregivers may be entitled to pension credits.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

The National Board of Health Supervision audits the different areas of the health system, both systematically across the nation and at individual organizations and professional practices. An alert system ensures that hospitals inform the board of serious adverse events, and the board may then decide to investigate particular incidents. The board can issue fines to institutions and warnings to health personnel and can revoke health care professionals’ authorization to practice in cases of misconduct. Local audits are performed by the county governors.

Accountability systems are changing. In 2017, regulation for “internal control for health services” was replaced with regulation for “leadership and quality improvement in the health services.” The change requires hospitals to undertake quality and safety improvement activities as well as to measure, and assume accountability for, performance.

National evidence-based guidelines, patient pathways, and bundles of care exist for several conditions, including stroke and cancer. Patient pathways are also being developed for mental health and addiction treatment. A five-year national safety program aims to improve patient safety, and a national reporting and learning system for adverse events in hospitals has been established.

Norway has 54 national clinical registries and 17 national health registries. Clinical registries, which are initiated by individuals, hospitals, or educational institutions, provide information for assessing the effects of treatments, including sometimes at the hospital ward level. They are used for quality assurance, research, and improvement activities. The national, statutory registries cover the entire population and, unlike the clinical registries, do not require patient consent (some are based on anonymous data). Since 2018, these registries and other health-related databases are the responsibility of the eHealth Directorate.

The Directorate of Health oversees a national program tracking health care quality indicators.14 The program includes results from national patient experience surveys, as well as such quality indicators as survival rates, infection rates, and wait times. No information is gathered or disseminated regarding the results or quality of individual health care professionals’ performance. Indicators for nursing homes are scarce and incomplete.

The Directorate of Health is also responsible for the licensing and authorizing of health care professionals. There is no system for reevaluation or reauthorization. The authority issues certificates of specialization to medical doctors in accordance with specific and transparent requirements. Only the specialization of GPs requires recertification.

RHAs, hospitals, municipal providers, and private practitioners are themselves responsible for ensuring the quality of their services. There is no requirement for accreditation or reaccreditation, although some hospitals or hospital departments are accredited.

A five-year developmental program for quality-based financing of RHAs, based on performance and improvement, ran from 2013 to 2017. This program measured 32 indicators, with patient experience constituting about 30 percent of metrics. Quality-based performance payments account for only about 0.5 percent of the RHAs’ budgets. A 2015 evaluation did not identify any disadvantages of this quality-based financing scheme, but did identify several areas for improvement.15 In 2016, the government decided to continue with quality-based financing at the current level.

The NIPH uses the Norwegian Prescription Database to produce annual reports on prescribing trends, giving national health authorities a statistical base for planning and monitoring drug prescriptions and use.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

The Patient and User Rights Act ensures that all inhabitants have equal access to quality health care.

A national 2013–2017 strategy, Equality and Equity in Health Care – Good Health for All, targeted social determinants of health. The emphasis has now shifted to individual health-related behaviors, rather than social determinants of health.16

The NIPH publishes data on social inequality and health. Information on disparities in outcomes and access to care is available through registries, and has been studied at the national and the regional level. Income disparities seem to be larger than educational disparities.17 The largest differences in life expectancy (nine years) are found among districts in Oslo.

Recent demographic studies of mortality differences between immigrant and Norwegian populations reveal no disadvantage for immigrants. Disparities between the indigenous people of northern Europe, the Sami, and Norwegian populations are studied through the SAMINOR population-based study.18 So far, there is little evidence for health disparities between the two.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

The 2012 care coordination reform emphasized the municipalities’ responsibility for 24-hour care and postdischarge care. In addition, the reform stipulated individual treatment plans for patients with chronic diseases. Hospitals and municipalities must establish formal agreements on the care of patients with complex needs.19

What is the status of electronic health records?

The eHealth Directorate is responsible for the national strategy for health information technology. The National Health Network, a state enterprise, provides efficient and secure electronic exchange of patient information between all relevant parties within the health and social services sector. It provides secure telecommunication for GPs, hospitals, nursing homes, pharmacists, dentists, and others.

All residents have a unique personal identification number, used in primary care and for hospital medical records. Virtually all GPs use electronic health records and transmit prescriptions electronically to pharmacies. Electronic communication systems are used for referrals, for communication with laboratories and radiology services, and for sick leave. Most GPs receive their patients’ hospital discharge letters electronically. Some GP and specialist outpatient offices have electronic booking, while most hospitals do not.

There is also a secure website for accessing patients’ core medical records. To gain access, health professionals must identify themselves, and their activity is logged.20 All adult patients have online access to their core medical records, which include an overview of prescribed medicines. (A separate website for information about prescriptions only is also available.) Patients can request access to their complete medical record.

After-hours emergency care is organized within the same patient record network as primary care, and primary care providers can access information regarding emergency visits. All hospitals use electronic records.

How are costs contained?

The central government sets an overall health budget annually, and the municipalities and RHAs are responsible for maintaining their budgets. About 10 percent of the RHAs’ operating expenses go to buy health services from private providers. Private providers are contracted through tender agreements, for which price of service is one of several criteria.

The RHAs have established a common procurement trust to negotiate volume-based discounts on supplies and drugs and to support environmentally friendly procurement practices. The trust has been especially effective in negotiating drug purchases.

The Norwegian Medicines Agency (NOMA) determines which medications to reimburse for outpatients. For new drugs, the agency determines whether a prescription drug should be covered by evaluating its cost-effectiveness in comparison with that of existing treatments. The agency decides the maximum price of drugs. NOMA’s drug-pricing scheme encourages the use of generic drugs and uses cost-effectiveness as a reimbursement criterion for drugs.

Health technology assessments (HTAs) are used systematically to inform decision-making regarding the adoption of new technologies. The system has two levels: Decisions at the national level are made jointly by the four RHAs and based on HTAs, while decisions at the local hospital level are based on mini-HTAs performed in each hospital. The level of assessment depends on the type of technology and its intended area of use. Certain technologies, such as drugs, are always assessed at a national level. The System for the Introduction of New Health Technologies also addresses cost-effectiveness, as does the national eHealth strategy.

Measures taken to reduce low-value care include clinical guidelines and a surgical atlas that tracks variation in the frequency of some procedures (www.helseatlas.no). Patient out-of-pocket-payments are another measure to contain costs.

An OECD analysis of health spending in Norway suggested that high staffing levels and high salaries could partly explain the higher health care prices in Norway.21 That perspective is also prominent in a report issued by the Directorate of Health.22 However, Norway’s wage negotiation model, which involves tripartite bargaining, has been successful in keeping costs at bay in recent years.23

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

In 2016, the government published a strategy for an “age-friendly society.” The goal is active, healthy aging through participation in and contribution to society. The government is also rolling out several other strategies through 2022, including a youth mental health and well-being program, an antibiotic-resistance initiative, and a mental health program aimed at adults.

The National Health Data Program, launched in 2018, aims to make health data available for government agencies, researchers, managers, health professionals, and residents.24

In 2017, municipalities and GPs were invited to participate in a primary care pilot project, which promotes the use of interdisciplinary teams as a primary tool for change. GPs are now responsible for the teams, under the leadership of each municipality. The project began in spring 2018 and will run until April 2021. The pilot includes testing of two new payment models: a fee-based model, similar to the existing funding model for GPs, and an operating grant based on the number and demographic characteristics of a GP’s patients. GPs also receive pay-for-performance bonuses and out-of-pocket payments.

In 2018, the government also introduced activity-based funding for specialized mental health services in combination with block grant financing.

In addition, a commission has been appointed to give advice on a new financing model for specialty care. The commission must consider the RHAs’ responsibilities for providing specialist care for the population, conducting research, and educating health personnel. The commission’s findings were set to be published in late 2019.

The government has started a process to decriminalize drug use as well as possession of minor quantities of drugs. The aim is to transfer the societal responsibility for handling minor drug offenses from the jurisdictional sector to the health care sector.

The author would like to acknowledge Anne Karin Lindahl, David Squires, and Ånen Ringard as contributing authors to earlier versions of this profile.