By Anna H. Glenngård, Lund University School of Economics and Management

Sweden’s universal health system is nationally regulated and locally administered. The Ministry of Health and Social Affairs sets overall health policy, the regions finance and deliver health care services, and the municipalities are responsible for the elderly and disabled. Funding comes primarily from regional- and municipal-level taxes. Grants are also provided by the central government. Enrollment is automatic. Covered services include inpatient, outpatient, dental, mental health, and long-term care, as well as prescription drugs. Regions set provider fees at all levels of care, as well as copayment rates for services such as primary care visits and hospitalizations. Dental and pharmaceutical benefits are determined nationally and are subsidized. Approximately 13 percent of employed residents have private supplemental coverage, mostly for improved access to private specialists.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

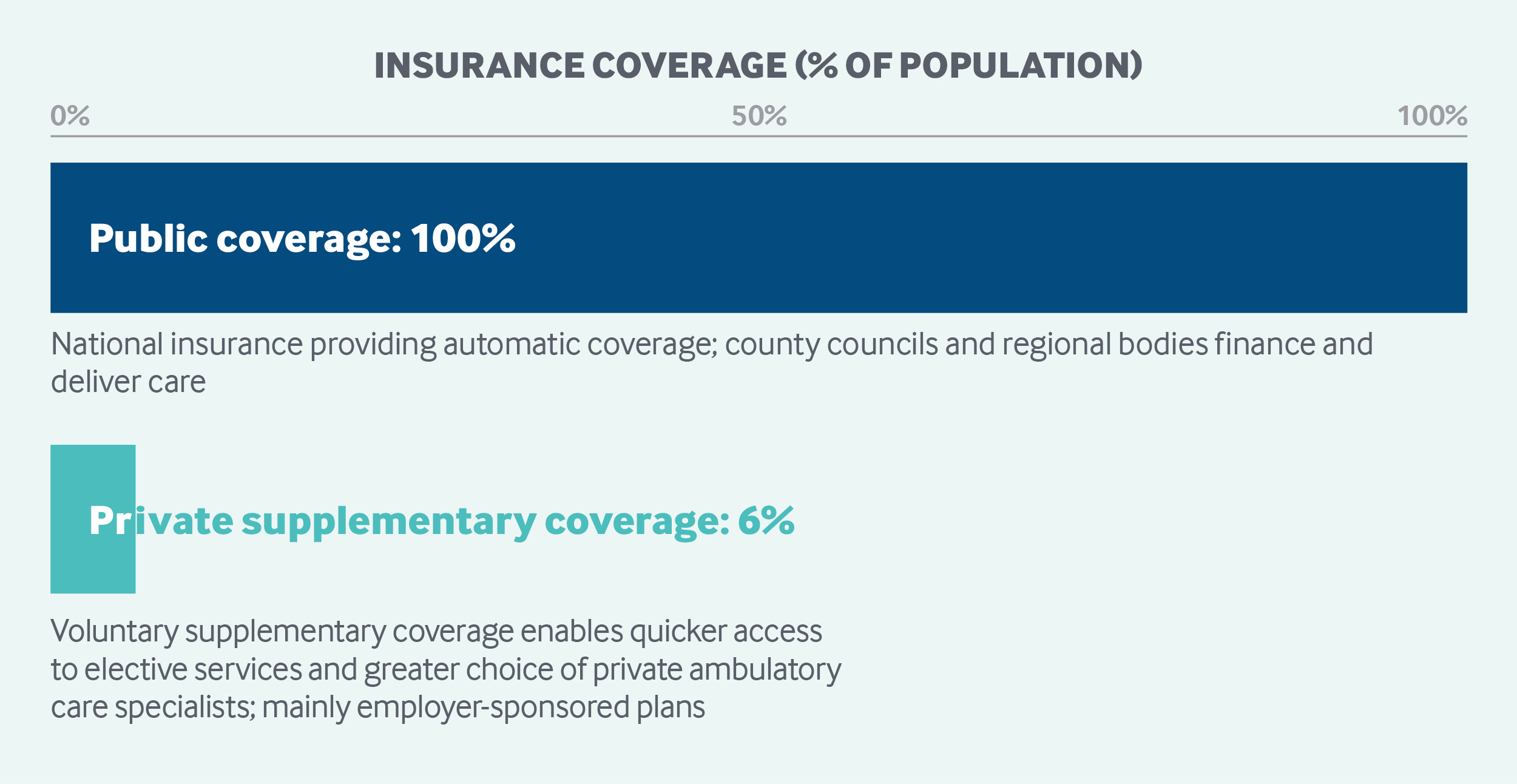

The Health and Medical Services Act states that Sweden’s health system must cover all legal residents.1 Coverage is universal and automatic. Emergency coverage is provided to all patients from the European Union, European Economic Area countries, and nine other countries with which Sweden has bilateral agreements. Asylum-seeking and undocumented children have the right to health care services, as do children who are permanent residents. Adult asylum-seekers and undocumented adults have the right to receive care that cannot be deferred, such as maternity care.

Three basic principles apply to all health care in Sweden:

- Human dignity: All human beings have an equal entitlement to dignity and have the same rights regardless of their status in the community.

- Need and solidarity: Those in greatest need take precedence in being treated.

- Cost-effectiveness: When a choice has to be made, there should be a reasonable balance between costs and benefits, with costs measured in relation to improvement in health and quality of life.

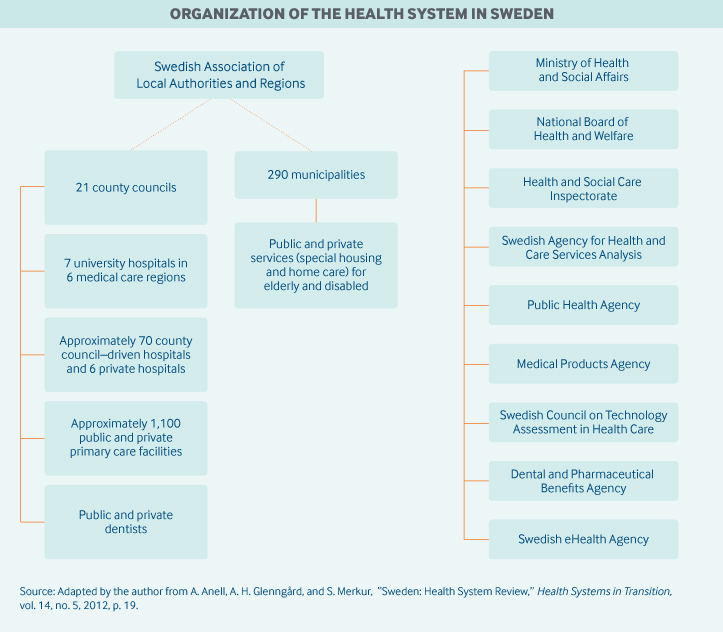

Role of government: All three levels of Swedish government are involved in the health care system.

- At the national level, the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs is responsible for overall health care policy and regulation and sets budgets for government agencies and grants to regions, working in concert with eight national government agencies.

- At the regional level, 21 regional bodies are responsible for financing and delivering health services to residents.

- At the local level, 290 municipalities are responsible for care of the elderly and the disabled, including long-term care.

The local and regional authorities are guided by local priorities and national regulation in their decisions. Nationally, they are represented by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR).

Eight independent government agencies are directly involved in medical care and public health:

- The National Board of Health and Welfare supervises and licenses all health care personnel, disseminates information, develops norms and standards for medical care (e.g., national guidelines for specific therapeutic areas), and, through data collection and analysis, ensures that those norms and standards are met. The agency also maintains health data registries and official statistics.

- The Swedish eHealth Agency promotes information-sharing among health and social care professionals and decision-makers. It stores and transfers electronic prescriptions issued in Sweden and is responsible for transferring electronic prescriptions abroad. The agency is also responsible for statistics on drugs and pharmaceutical sales.

- The Health and Social Care Inspectorate is responsible for supervising health care, social services, and activities concerning support and services for people with disabilities. It is also responsible for issuing permits in those areas.

- The Swedish Agency for Health and Care Services Analysis analyzes and evaluates health policy and the availability of health care information to citizens and patients.

- The Public Health Agency provides the national government, government agencies, municipalities, and regions with evidence-based knowledge regarding infectious-disease control and public health.

- The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care promotes the use of cost-effective health care technologies. The council reviews and evaluates new treatments from medical, economic, ethical, and social points of view.

- The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency is the principal agency for assessing pharmaceuticals. Since 2002, it has had a mandate to decide whether particular drugs and medical devices should be included in the National Drug Benefit Scheme; prescription drugs and medical devices are priced, in part, on the basis of their value. The agency’s mandate also includes dental care.

- The Medical Products Agency is the Swedish national authority responsible for the regulation and surveillance of the development, manufacture, and sale of drugs and other medicinal products.

Role of public health insurance: Health expenditures accounted for 10.9 percent of GDP in 2016. About 84 percent of this spending was publicly financed, with regions’ expenditures amounting to almost 57 percent, municipalities’ up to 25 percent, and the central government’s to almost 2 percent.2 In 2016, 88 percent of regions’ total spending was on health care.3 The regions and the municipalities levy proportional income taxes on their populations to help cover health care services. In 2016, 70 percent of the regions’ total revenues came from local taxes and 16 percent from subsidies and national government grants, which are financed by national income taxes and indirect taxes. General government grants are designed to redistribute resources among municipalities and regions based on need. Targeted government grants finance specific initiatives, such as reducing wait times.

Role of private health insurance: Private health insurance, in the form of supplementary coverage, accounts for less than 1 percent of health expenditures. It is purchased mainly by employers and is used primarily to guarantee quick access to an ambulatory care specialist and to avoid wait lists for elective treatment. In 2017, 633,000 individuals had private insurance, representing roughly 13 percent of all employed individuals ages 16 to 64 years.4

Services covered: There is no defined benefit package. Because the responsibility for organizing and financing health care rests with the regions and municipalities, services vary to some extent throughout the country. Broadly, however, the publicly financed health system covers the following:

- Public health and preventive services

- Primary care, including maternity care

- Inpatient and outpatient specialized care

- Emergency care

- Inpatient and outpatient prescription drugs

- Mental health care

- Rehabilitation services, including physical therapy

- Disability support services, including durable medical equipment such as wheelchairs and hearing aids

- Patient transport support services

- Home care and long-term care, including nursing home care and hospice care

- Dental care and optometry for children and young people

- Adult dental care with limited subsidies.

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: In 2016, about 16 percent of all health expenditures were private; of these, 92 percent were out of pocket.5 Most out-of-pocket spending is for drugs and dental care.6

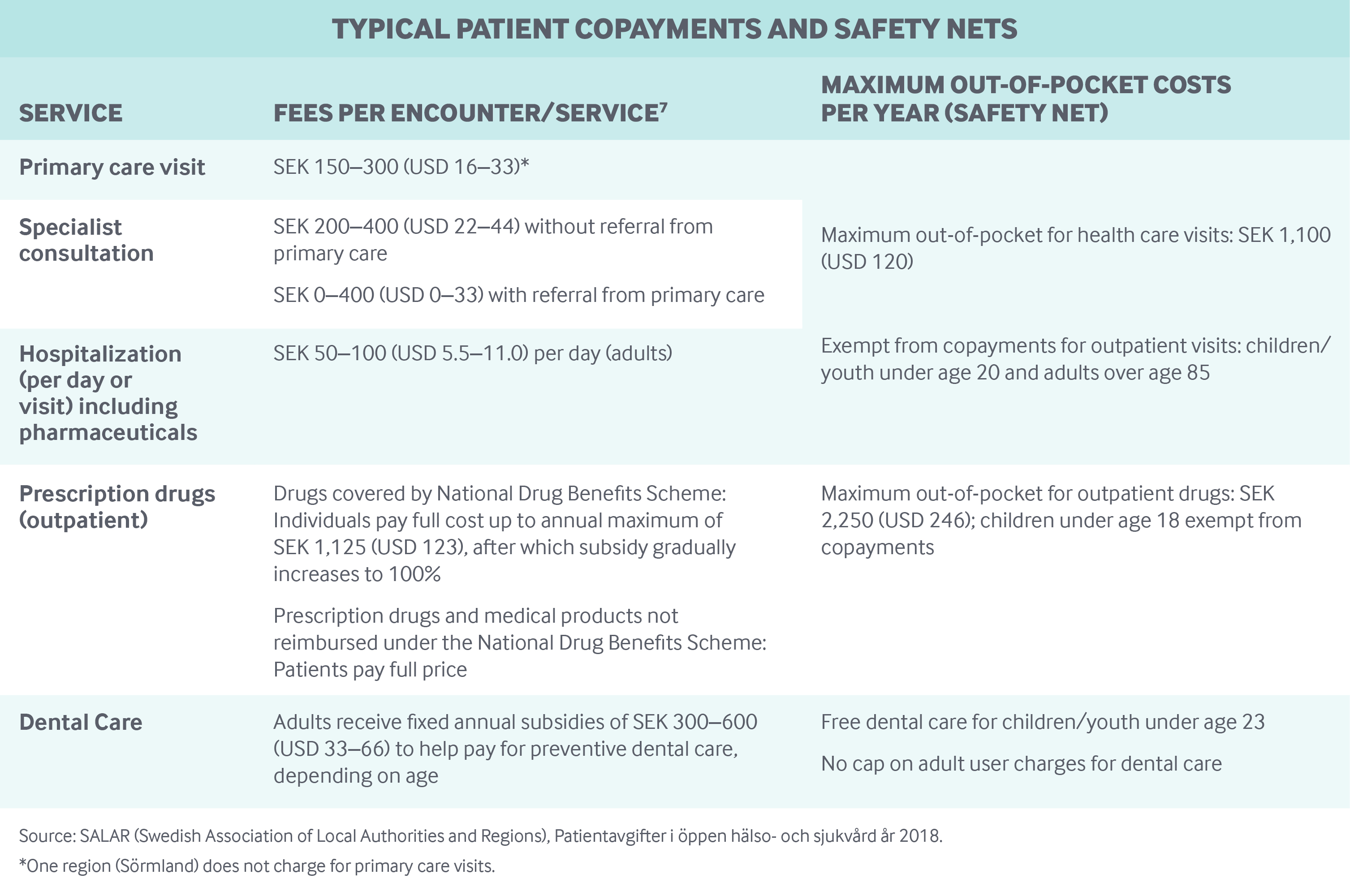

The regions set copayment rates for outpatient visits and hospital stays, leading to some variation across the country (see table below). However, pharmaceutical and dental benefits are determined by the national government and apply to all residents.

Safety nets: In general, all social groups are entitled to the same benefits. Ceilings on out-of-pocket spending (see table below) apply to everyone, and the overall cap on user charges is not adjusted for income. Some targeted groups, such as children, adolescents, and the elderly, are exempt from user charges. In addition, preventive services, such as maternity care, immunizations, and cancer screenings, do not have copayments.

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: Medical schools are public, and there is no tuition fee for medical education; however, the number of students accepted each year is limited.

Primary care: Primary care accounts for about 17 percent of all health expenditures,8 and about 16 percent of all physicians work in this setting.9

There are about 1,200 primary care practices; 60 percent are owned by regions and the remainder are privately owned. Regions control the establishment of new private practices by regulating clinic hours, clinical competencies, and other organizational aspects and by regulating financial conditions for accreditation and payment. The right to establish a practice and be publicly reimbursed applies to all public and private providers fulfilling the conditions for accreditation.

Team-based primary care, comprising GPs, nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, and psychologists, is the main form of practice. There are an average of four to five GPs in a primary care practice.

District nurses, employed by municipalities, coordinate care for patients with chronic illness or complex needs, especially the elderly; they have limited prescribing authority. These nurses also participate in home care and regularly make home visits.

All provider fees at all levels of care are set by regions. Providers cannot bill above the fee schedule.

Primary care centers (public and private) are paid through a combination of payments:

- Fixed capitation for registered individuals (accounting for 60%–95% of total payment)

- Fee-for-service (accounting for 5%–38% of payment)

- Performance-related bonuses (0%–3% of payments) for achieving quality targets related to patient satisfaction, care coordination, compliance with evidence-based guidelines, and other metrics.

Public and private physicians (including GPs and hospital specialists), nurses, and other categories of health care staff at all levels of care are predominantly salaried employees. Primary care physicians in the centers are paid a salary, determined at the regional level or by private providers. There is a general shortage of physicians in primary care, especially in more remote locations. This leads to higher salaries in such areas to attract physicians.

While there is no formal gatekeeping function, general practitioners (GPs) or district nurses are usually the first point of contact for patients. People can choose to register with any public or private provider accredited by the local region; most individuals register with a practice instead of with a physician. Registration is not required to visit a practice. In primary care, there is competition among providers (public and private) to register patients, although providers cannot compete through pricing because the regions set fees.

There is no regulation prohibiting physicians (including specialists) and other staff who work in public hospitals or primary care practices from also seeing private patients outside the public hospital or primary care practice. Employers of health care professionals, however, may establish such rules for their employees.

Outpatient specialist care: Outpatient specialist care is provided at university and regional hospitals and in private clinics. In both cases, specialists are salaried employees (of hospitals and clinics). Patients are free to choose a specialist.

Public and private specialists are paid through a combination of global budgets and per-case payments based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), which are determined at the regional level. Price or volume ceilings and quality-related bonuses may also apply.

The average monthly salary for a physician specialist (including general medicine specialists working in primary care) was SEK 77,900 (USD 8,532) in 2018.10 Regions set fee schedules, while salaries are determined by the regions and by private clinics in their role as employers.

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Patients normally pay out-of-pocket fees up front for primary care and other outpatient visits, including specialty physician visits. In most cases, it is also possible for patients to pay later.

After-hours care: Primary care providers are required to provide after-hours care. Often, three to five primary care practices located close to each other collaborate to provide after-hours arrangements. Through their websites and phone services, providers advise registered patients where to go for care. Regions and regional bodies also provide information on how and where to seek care through their websites and a national phone line, with medical staff available all day to give treatment advice.

Staff providing primary care services after hours normally include GPs and nurses. The same patient copayments apply as during regular hours.

In addition, to reduce emergency care use at hospitals, urgent care centers in some areas are typically open 8 a.m. to 10 p.m.

Hospitals: There are seven university hospitals, all public, and about 70 public community hospitals owned by the regions. There are also six private hospitals, of which three are not-for-profit. Private hospitals include emergency, orthopedic, and surgery centers. All hospital staff are salaried employees.

Acute-care hospitals (seven university hospitals and two-thirds of the 70 region hospitals) provide full emergency services. Swedish counties are each grouped into six health care regions to facilitate cooperation among providers and to maintain a high level of advanced medical care. Highly specialized care, often requiring the most advanced technical equipment, is concentrated in university hospitals to ensure high quality and greater efficiency and to create opportunities for development and research.

A mix of global budgets, DRGs, and/or performance-based methods is used to reimburse hospitals. The use of global budgets, set by regions, is most common. When DRGs are used, they constitute less than half of total payments. Performance-based payments related to meeting quality targets constitute less than 5 percent of total payments. Payments are traditionally based on historical (full) costs.

Mental health care: Mental health care is an integrated part of the health care system and is subject to the same legislation and user fees as other health care services. Specialized inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, including that related to substance use disorders, is available to adults, children, and adolescents.

People with minor mental health problems are usually attended to in primary care settings, either by a GP or by a psychologist or psychotherapist. Patients with severe mental health problems are referred to specialized psychiatric care in hospitals.

Long-term care and social supports: Responsibility for the financing and organization of long-term care for the elderly and for the support of people with disabilities lies with the municipalities (financed through taxation). However, the regions are responsible for patients’ routine health care. Older adults and disabled people incur a separate maximum copayment for services commissioned by the municipalities, which was SEK 1,772 (USD 194) per month in 2016.

The Social Services Act specifies that adults at all later stages of life have the right to receive public services and assistance, such as home care aids, home care, and meal deliveries. Eligibility for services and assistance is based on need, which is determined by care managers from the municipality together with the client and often a relative. Means-testing does not play a role.

End-of-life care is also included, either in the individual’s home or in a nursing home or hospice. The Health and Medical Services Act and the Social Services Act regulate how the regions and the municipalities manage palliative care. The organization and quality of palliative care vary widely both between and within regions. Palliative-care units are located in hospitals and hospices. An alternative to palliative care in a hospital or hospice is advanced palliative home care.

There are both public and private nursing homes and home care providers. About 24 percent of all nursing home and 18 percent of all home care was privately provided in 2017,11 although the percentage varies significantly among municipalities. Payment to private providers is usually contract-based, following a public tendering process.

In general, Sweden aims to have individuals stay in ordinary housing rather than in nursing homes. National policy promotes home assistance and home care over institutionalized care, with older people entitled to live in their homes for as long as possible. Municipalities can also reimburse informal caregivers, either directly (relative-care benefits) or by employing the informal caregiver (relative-care employment). Among adults with long-term care needs in 2017, 72 percent had their needs met through home care and 28 percent in institutions.12

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

Regions are responsible for ensuring that health care providers deliver services of high quality and adhere to national therapeutic guidelines. Providers are evaluated for meeting quality targets associated with a pay-for-performance scheme or accreditation requirements. They are also assessed based on information from patient registries and national quality registries, patient satisfaction surveys, and dialogue meetings between providers and regions.

Concern for patient safety has increased during the past decade. Patient safety indicators are compared regionally by SALAR, and the results are publicly disseminated in many cases. Eight priority target areas for preventing adverse events have been specified13:

- Health care–associated urinary tract infections

- Central line infections

- Surgical site infections

- Falls and fall injuries

- Pressure ulcers

- Malnutrition

- Medication errors in health care transitions

- Drug-related complications.

Disease management programs, developed at the regional level, also encompass quality and patient safety targets and strategies.

To reduce unnecessary variation in clinical practice, there has been a trend toward development of regional guidelines. For example, the National Cancer Strategy was established in 2009, and six Regional Cancer Centers (RCCs) were formed in 2011. The RCCs’ role is to contribute to more equitable, safe, and effective cancer care through regional and national collaboration.

More than 100 national quality registries are used for monitoring and evaluating quality among providers and for assessing treatment options and clinical practice. Registries store individualized data on diagnosis, treatment, and treatment outcomes in inpatient and outpatient care (including primary care) and nursing homes. The registries are funded by the central government and by the regions, are managed by specialist organizations, and are monitored annually by an executive committee.

Since 2006, the government has published annual performance comparisons and rankings of the regions’ health care services, using data from the national quality registers, the National Health Care Barometer Survey, the National Waiting Time Survey, and the National Patient Surveys. Performance comparisons for specialty care, primary care, nursing homes, and home care are publicly released. The 2015 publication included 350 indicators organized into various categories, such as prevention, patient satisfaction, wait times, trust, access, surgical treatment, and drug treatment. In addition, some 100 indicators for hospitals are tracked, but without rankings. Statistics on patient experience and wait times in primary care are also made available online by SALAR ( www.skl.se) to help guide people in their choice of provider.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

Sweden ranks in the top three among 11 high-income countries on measures related to health care equity.14 The Health and Medical Services Act emphasizes equal access to services according to need and a vision of equal health for all, and the level of unmet need is very low in Sweden.15 Disparities in access and health outcomes are measured primarily with regard to gender, income, and education by the National Board of Health and Welfare and the Public Health Agency.

Disparity-reduction approaches include programs to support behavioral changes and outpatient preventive programs targeting vulnerable groups. To prevent primary care providers from avoiding patients who have extensive needs, most regions allocate funds based on a formula that accounts for both overall illness (based on adjusted clinical groups) and registered individuals’ socioeconomic conditions (measured through the Care Need Index).

Another health care disparity issue relates to unwarranted regional variation in wait times and access to different services. One way in which such inequalities are addressed is through evidence-based clinical guidelines and performance indicators set by the government, sometimes accompanied by targeted grants. Moreover, in 2005 (regulated in the Health and Medical Services Act since 2010 and the Patients Act since 2015), Sweden introduced a wait-time guarantee—the 0–7–90–90 rule—to improve and ensure equal access to services across the country:

- 0: zero delay, or instant contact with the health system for advice

- 7: seeing a general practitioner within seven days

- 90: seeing a specialist within 90 days

- 90: waiting no more than 90 days to receive treatment after being diagnosed.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

The Swedish health system is highly integrated. The dividing of regional responsibility (for medical treatment) and municipal responsibility (for nursing and rehabilitation) requires coordination. Efforts to improve collaboration and develop more integrated and accessible services are supported by targeted government grants. Since 2015, the targeted grants have focused on care coordination; they support action plans for improving coordination and collaboration at the regional level.

At the provider level, performance-related payment is commonly linked to quality targets related to care coordination and compliance with evidence-based clinical guidelines, particularly for care provided to elderly patients with multiple diagnoses.

In addition, since the 1990s, policies have focused on shifting inpatient care to outpatient and primary care settings and on concentrating highly specialized care in academic medical centers.

What is the status of electronic health records?

In 2016, the government developed a vision of Sweden as a world leader in e-health by 2025. The strategy involves four overarching tactics:

- coordination and communication among health care stakeholders

- development of common concepts in the field

- implementation of standards for health information exchange

- creation of national drug lists that assist health care professionals in efforts to improve patient safety.

High-quality information technology systems are deployed in hospitals and primary care practices, and adoption rates are high in these settings as well. However, the types of systems used vary by care setting and by region.

Patients age 16 and older can increasingly access their electronic medical records to view personal health data, read physician’ notes, schedule appointments, and refill prescriptions. According to the Swedish eHealth Agency, 99 percent of all Swedish prescriptions were e-prescriptions in 2017.

To access their records, patients log in using a personal identification number (the same 10-digit number used for accessing all public services) and a personal electronic encryption code called BankID. The level of information available to patients varies to some extent across regions.

How are costs contained?

Regions and municipalities are required by law to set and balance annual budgets for their activities and to consider the cost-effectiveness of different treatment alternatives when organizing care. For prescription drugs, the central government and the regions form agreements, lasting a period of years, on the subsidy levels paid by the government to the councils.

The central government’s Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency also employs value-based pricing for prescription drugs, determining reimbursement based on an assessment of health needs and cost-effectiveness. Some regions also use value-based pricing models for specialized care, such as knee replacements.

Because regions and municipalities own or finance most health care providers, they can undertake a variety of cost-control measures. For example, contracts between regions and private specialists are usually based on a tendering process in which costs constitute one of the variables used to evaluate providers. The funding of health services through global budgets, volume caps, capitation formulas, and contracts also contributes to cost control, as providers retain responsibility for meeting costs with funds received through those prospective payment mechanisms. In several counties, providers are also financially responsible for prescription costs.

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

Important policy areas that have been under scrutiny at both the local and the national level during the past few years include the quality and equity of care, wait times, coordination of care for the elderly, and investment in e-health.

The 2015 Patient Act sought to strengthen the rights of patients and encourage shared decision-making. It clarifies and expands providers’ responsibilities in conveying information to patients, guarantees patients the right to a second opinion, and ensures choice of provider in outpatient specialty care. It also strengthens the wait-time guarantee by clarifying patients’ right to seek care in any region.

Accurate reporting and monitoring to measure quality, equity, and efficiency remain important challenges in Swedish primary care and are a concern for policymakers. A new quality register for primary care was set up in 2017, coordinated by SALAR.

To improve the continuity and coordination of care, in 2014 the government launched a four-year national initiative for people with chronic diseases. Its three areas of focus are patient-centered care, evidence-based care, and prevention and early detection of disease. Regional implementation of various initiatives began in 2017–2018, among them, a team-based care program for frail elderly patients.

In the area of specialized care, there have been recent efforts to foster greater equity. The government has committed to providing SEK 500 million (USD 55 million) per year from 2015 to 2018 to reduce wait times in cancer care and to reduce regional disparities. The initiative has led to the development of standardized care processes and reduced wait times in some cancer areas, but not in all regions. The learnings from this work are being applied in additional areas in 2018.

General discussions about how governance, including reimbursement systems, can promote innovation and trust are also taking place. The government aims to promote governance models that put greater trust in public-sector professionals to provide high-quality care to citizens. In part, this approach may be a response to pushback on past reforms aimed at increasing competition and the monitoring of providers based on performance indicators.