Abstract

- Issue: State legislators continue to pursue reforms aimed at reducing health care costs. But the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) threatens enforcement of state laws that impact employer-sponsored health insurance, especially the self-funded plans that comprise 64 percent of employer-sponsored coverage. ERISA preempts state laws directly targeting these plans and stretches into topics with only a tangential relationship to employer insurance. Preemption dilutes states’ ability to collect data, control prices, and protect consumers.

- Goals: Identify types of health care cost reforms states have pursued since 2019 and assess the ERISA preemption implications for those state reforms.

- Methods: Survey state health bills relating to health care costs passed from 2019 to June 2021, identify common provisions, and analyze the ERISA preemption implications for those provisions.

- Key Findings and Conclusions: States recently passed an array of reforms, mostly targeting prescription drug costs, provider reimbursement, consumer protection, data collection on health care spending, and insurance coverage. Many of these reforms are fully enforceable, but ERISA preemption threatens some popular measures as applied to employers’ self-funded plans. While recent Supreme Court precedents limit ERISA preemption’s application, the law still poses an obstacle to state cost-control reforms — whether ambitious or modest.

Introduction

States have an especially keen interest in reducing the burden of health care costs. State governments pay a large portion of these costs through public programs and as an employer responsible for state employees’ health care needs. Unlike the federal government, many states are bound by law to balance their budgets and, therefore, must divert funds from other priorities when health care costs increase.1 Federal law impacts states’ capacity to enforce these urgently needed health reforms in several ways:

- Federal programs may fund state health care reform efforts, such as in the Medicaid program and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) state insurance exchanges.

- Federal law may create minimum standards and protections to which state law may add, such as the ACA’s requirement that insurers cover a set of essential health benefits.

- Federal law preempts the enforcement of state law to the extent that the two conflict, usually instances where a state law would permit less protective regulation than federal law requires.

In health reform, states also must contend with a federal hurdle in the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA).2 ERISA preempts state laws that directly regulate employers’ health benefit choices, and it preempts some state laws that only indirectly relate to those choices, too. An employer’s choice of how to fund health benefits is particularly relevant to the strength of ERISA preemption. Under fully insured employer-sponsored plans, the insurer sets the benefits and takes on most of the financial risk. Employers that choose a self-funded approach assume most of the financial risk and have more flexibility to design employee benefits. While states may regulate insurers that sell group plans to employers, ERISA preempts states from enforcing insurance regulations on self-funded employer-sponsored health plans.

For example, ERISA would preempt a state law directing employers to offer health benefits for infertility treatment. However, a state law requiring that health insurance cover infertility treatment would be enforceable on insurers selling group plans. So, if an employer chose to offer a fully insured plan, the carrier selling that plan would have to cover the infertility treatment. But if the employer chose instead to self-fund its plan, ERISA would preempt enforcement of the state law and the employer would not have to cover infertility treatment in its plan.

In contrast to many other preemptive federal laws, ERISA creates relatively little federal regulation for employer-sponsored insurance,3 leaving a void of preemption in which state law is unenforceable and federal law is nonexistent. The breadth and indeterminacy of the statute’s preemption language make it easier for employers and other entities to mount litigation challenging the enforcement of state law. That litigation consumes state governments’ time and resources in defending their laws, even if they ultimately prevail.

Because employer-sponsored health insurance provides coverage for nearly half of all people in the U.S., ERISA’s preemption of state law that relates to employer-sponsored insurance puts a major obstacle in the path of state health reform.4

The Supreme Court’s interpretation of ERISA has left states a few narrow avenues. States may not enforce laws that reference or “act immediately and exclusively upon” employer-sponsored plans, nor may state law have too direct a connection with those plans by intruding on “central matters of plan administration,” such as recordkeeping and claim processing.

But state laws that have only indirect economic effects on employer-sponsored plans avoid preemption. The U.S. Supreme Court’s December 2020 opinion in Rutledge v. PCMA further clarified that state laws that “merely” affect or regulate health care costs are not preempted even though they may alter the incentives and decisions facing employer-sponsored plans.5 The state law in Rutledge required pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to reimburse pharmacies for covered drugs at or above their acquisition cost. The Court held that this regulation applied to PBMs as contractors for employer-sponsored plans does not “directly regulate health benefit plans at all.” The incidental costs of compliance that PBMs might pass along to employer plans, according to the Court, are merely an “indirect economic influence” on health plans that do not trigger ERISA preemption.

This issue brief surveys state legislation influencing health care costs over the past three years and assesses the threat that ERISA preemption poses for the enforcement of these reforms.

Key Findings

States have passed a wide variety of laws aimed at health care costs. Many are designed to have some impact on the commercial group market for health insurance and, therefore, carry at least some potential for ERISA preemption.

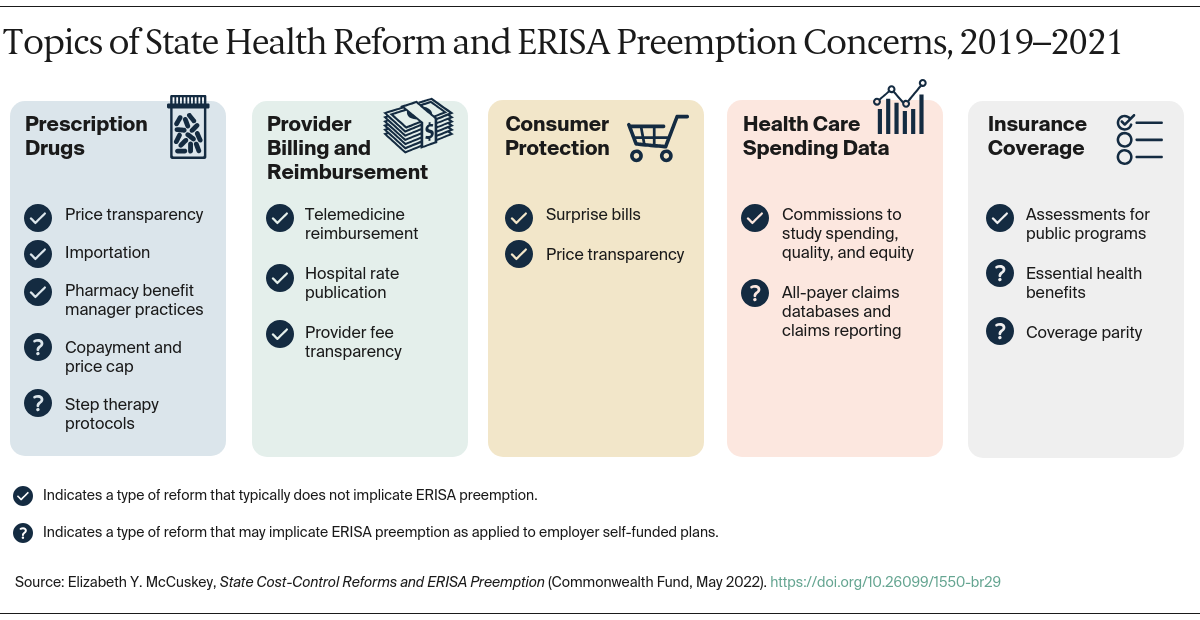

We examined a sample of more than 300 state health reform bills passed between January 1, 2019, and August 1, 2021, for their ERISA preemption potential.6 Most state legislative efforts during this period fall into one or more general categories of reform: prescription drugs, provider reimbursement, consumer protection, data collection on health care spending, and insurance coverage.

The majority of these efforts exist outside the reach of ERISA preemption because they regulate providers, manufacturers, and patients — rather than payers — and because they tend to enact modest incremental changes, such as transparency of cost information. The threat of ERISA preemption litigation, however, lingers even for relatively modest state laws, as well as for the few more ambitious and transformative efforts.