During the most recent open enrollment period, the ARPA’s subsidy expansion made marketplace coverage more affordable than ever. To learn more about the outreach strategies deployed to ensure consumers took advantage of more generous financial assistance, we surveyed the 21 state-operated ACA marketplaces. Seventeen SBMs responded to our survey.

Key Findings

Outreach strategies of SBMs during this historic enrollment period underscore the importance of adequately funding enrollment assistance and marketing campaigns, providing enough time to enroll in coverage, and using targeted communications as well as broader messaging to reach the uninsured. In addition to investing more in outreach, marketplace survey respondents cited these other actions as effective in encouraging enrollment: extension of the enrollment period, promotion of more-affordable plans, data-driven campaigns, culturally and linguistically appropriate outreach, and coordination with health care providers and other state services.

Most Marketplaces Increased Investments in Advertising and Enrollment Assistance

Following the Trump administration’s significant cuts to the federal marketplace outreach budget, the Biden administration increased funding for FFM marketing and navigator grants.14 Most SBMs in our survey also increased funding for efforts to broadcast the annual enrollment opportunity and help consumers sign up for coverage.

Of the 17 SBMs that responded to our survey, more than half increased their budget for enrollment assisters, who provide one-on-one help to consumers during the sign-up process. A majority of SBM respondents also increased their advertising budget for activities including television, radio, print ads, and other efforts to promote enrollment.15

Several SBMs noted that funding from federal grants supported successful enrollment efforts. This includes modernization grants authorized under the ARPA, which allocated $20 million in funding for SBMs to modernize or update “any system, program, or technology.”16 New York, for example, indicated their modernization grant funded advertising and translations of ARPA-specific messaging, illustrating the importance of federal funding to enrollment efforts even in state-operated marketplaces.

Marketplaces Gave Consumers More Time to Enroll in Coverage

In addition to increasing funding for marketing and enrollment assistance, all SBMs extended the annual open enrollment period beyond 45 days,17 a policy associated with better enrollment outcomes.18 All but one SBM extended the enrollment period into the beginning of the plan year,19 allowing consumers who are automatically renewed into coverage to return to the marketplace after receiving their January bill — which may be higher than they anticipated because of annual premium changes — and enroll in a more-affordable plan.

Respondents that launched new SBMs just before open enrollment credited their extended enrollment window with encouraging coverage take-up. Maine’s new SBM saw a nearly 14 percent increase in new enrollees,20 with many of those consumers signing up during the extended enrollment period. In Oregon, a state operating an SBM that uses the federal marketplace platform HealthCare.gov, consumers shopping for marketplace plans the previous year only had until December 15 to sign up for coverage. In its survey response, the marketplace noted that this year, the Biden administration’s decision to extend the enrollment period on the federal platform until January 15 “contributed significantly” to increased plan selections.21

Affordability Messaging Encouraged Enrollment

Most survey respondents providing information on successful outreach strategies indicated that their messaging around the ARPA’s premium subsidy expansion and more-affordable plan options encouraged enrollment. Colorado, which saw a nearly 21 percent increase in new enrollees compared with the last open enrollment period,22 noted that the savings prompted consumers to “take a second look” after previously determining that they could not afford coverage. Similarly, Vermont, a marketplace that also saw an increase in new enrollees,23 communicated that “if health insurance seemed expensive in the past, it’s time to look again.” Maryland, which had nearly 50 percent more new enrollees this year,24 underscored the success of working with social media influencers to reach consumers who were newly eligible for subsidies under the ARPA and young adults who qualified for additional, state-funded subsidies.

Marketplaces Used Data to Reach the Uninsured

SBM survey respondents also highlighted the use of uninsured data as a successful strategy for enrolling people in need of coverage. Rhode Island, for example, created an on-the-ground “street team” to distribute door hangers, flyers, brochures, and posters in zip codes likely to have uninsured residents based on state-procured data. Washington also identified geographic areas with high uninsured rates and customized advertising based on information about population demographics and preferred media channels. New York targeted outreach toward industries with higher concentrations of uninsured workers and those presumed to be hit hard by the pandemic, including the service industry, small businesses, and self-employed individuals.

Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Outreach Promoted Awareness and Take-Up of Subsidized Coverage

Language barriers are associated with lack of insurance and challenges with the sign-up process.25 SBMs attributed their enrollment successes, in part, to ongoing efforts to mitigate these barriers and help historically underserved populations access coverage. Rhode Island, which noted an increase in enrollees who self-identified as Hispanic, distributed all outreach and communication materials in both English and Spanish (including those for door-to-door outreach and a media campaign) and posted flyers and posters at Spanish-speaking religious congregations. Nevada reported that Spanish-language campaigns outperformed English-language campaigns on almost every paid media platform.

Marketplaces also offered and promoted linguistically appropriate enrollment assistance. The District of Columbia, for example, provided interpreters during a biweekly initiative to give consumers virtual, one-on-one enrollment assistance. Minnesota placed translated advertisements in publications serving Hmong, Somali, and Spanish speakers that emphasized how the marketplace assister network could help consumers in their preferred language.

Culturally appropriate outreach is key to addressing current gaps in knowledge of health insurance eligibility.26 And here, too, SBMs continued their efforts to reach underserved populations. Oregon described the success of video content created for outreach to the state’s Latino/Hispanic population. Nevada also emphasized the importance of authenticity in outreach to Latino/Hispanic consumers, indicating that community partnerships and radio broadcasts contributed to greater outreach impact in these communities. Colorado, which targeted outreach toward LGBTQ, Latino/Hispanic, Black, and rural communities, created representative content and invested in assistance resources to serve these populations.

Coordination with Other State Services and Health Care Providers

SBMs also encouraged enrollment by partnering with other state programs and agencies, as well as health care providers, to reach residents who are more likely to be uninsured. Maine, for example, worked with the state labor department to provide information to consumers applying for unemployment insurance. In Virginia, which saw an almost 18 percent increase in overall plan selections,27 navigators reached new marketplace customers through referrals from social services and health departments.

Respondents also described successful outreach efforts in health care settings, including advertising at pharmacies, health clinics, hospitals, and COVID-19 vaccination and testing sites.

Discussion

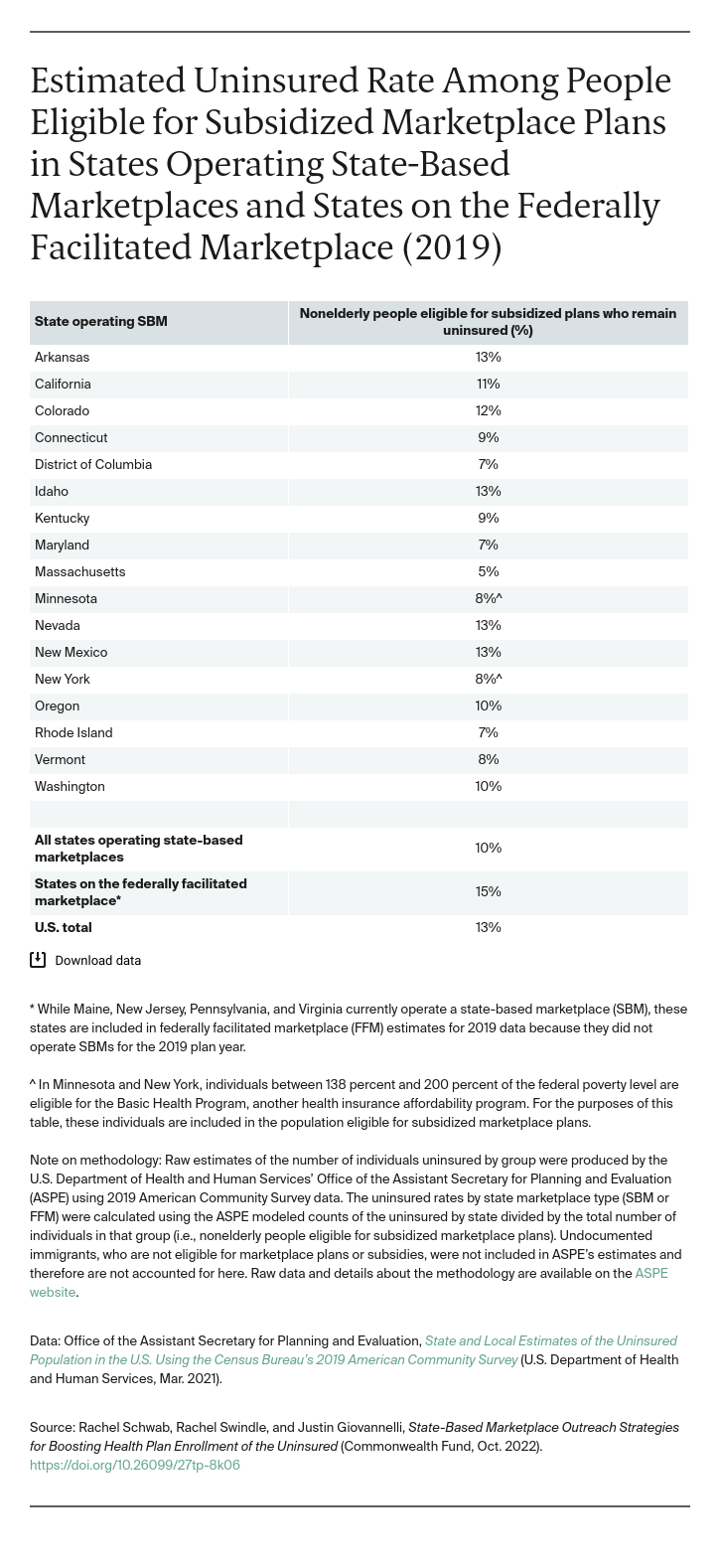

Extension of the ARPA’s subsidy enhancements through the Inflation Reduction Act28 — under which an estimated half of nonelderly uninsured people are eligible for either subsidized marketplace plans or employer coverage — will allow marketplaces to sustain and build on recent coverage gains.29 But expanded subsidies have not eliminated the perception that health insurance is too expensive: some uninsured consumers may still be deterred from visiting the marketplaces in the first place, even if they now qualify for free or low-cost plans. Difficulty with the sign-up process also reduces coverage take-up. Consequently, the historic enrollment seen this year likely would not have been possible without robust and innovative advertising campaigns and the availability of enrollment assistance.

Marketplaces are bracing for an influx of new enrollees at the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), when Medicaid redeterminations recommence and millions of current Medicaid beneficiaries lose coverage.30 In addition to protecting and extending coverage gains of the ARPA’s subsidy expansion in future open enrollment periods, lessons learned during the marketplaces’ most successful enrollment season provide insight on how to improve take-up among newly marketplace-eligible consumers. Partnerships and data-driven initiatives can help marketplaces identify and reach people who have recently lost or will lose Medicaid. Broadcasting the availability of more-affordable plans may draw more people to marketplaces, including those who previously found coverage out of reach and former Medicaid beneficiaries who are unfamiliar with the marketplace. Enrollment assistance and advertisements reflecting the linguistic and cultural diversity of marketplace-eligible consumers better convey the message that free and low-cost coverage is available. Finally, greater funding for outreach efforts and extended enrollment windows, such as longer special enrollment periods for those losing Medicaid coverage at the end of the PHE, may increase the impact of outreach and improve coverage take-up.