Abstract

- Issue: The U.S. primary health care system does not effectively meet women’s needs as they age and transition through stages of life.

- Goal: Describe gaps and barriers in women’s primary health care and propose a framework for transforming the system so that it can meet the needs of women of all ages, races/ethnicities, and socioeconomic backgrounds throughout their lives.

- Methods: Literature review, expert interviews, and an all-day expert convening with innovators, primary care providers, advocates, policymakers, and payers.

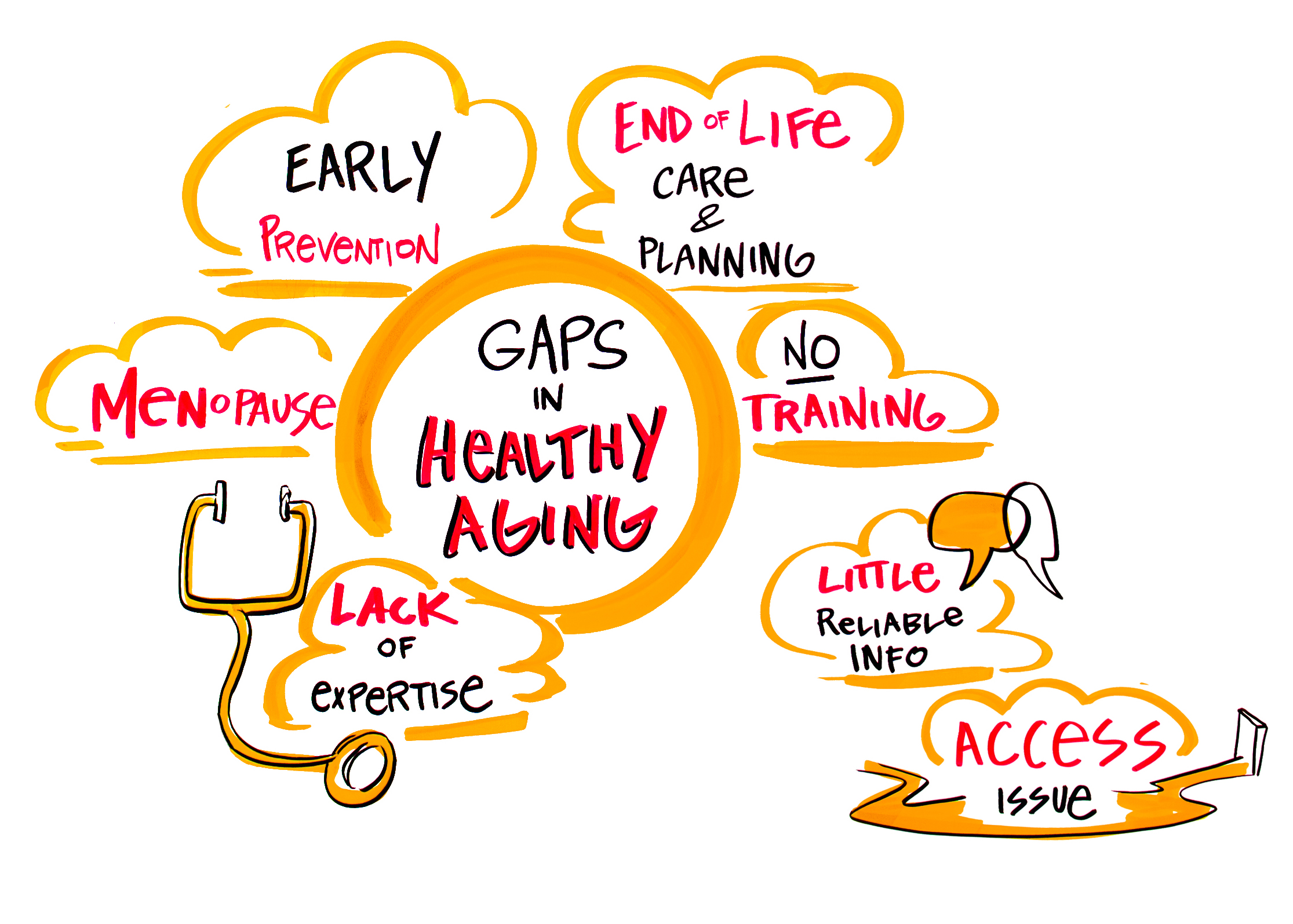

- Findings: Major gaps and barriers inhibit the primary health care system from meeting the physical, behavioral, and social needs of women across the life course, including: gaps in medical training; barriers to utilization and delivery, including biases, time constraints, lack of focus on social factors, and competing professional and personal obligations; access barriers related to language, culture, and lack of a regular source of primary care; underrepresentation of women in health care leadership and policymaking; and the politicization of women’s health issues.

- Conclusion: We propose a framework for transforming primary health care for women of all ages and at all stages of life that provides comprehensive care, delivers sex-specific, sex-aware, and gender-sensitive care, and adeptly manages and coordinates care for an array of health experiences.

Introduction

Recently, the vital role that primary health care plays in the U.S. health system has received renewed attention. Primary health care is associated with positive health outcomes; regions that have more primary health care providers are associated with lower rates of hospitalization, cancer mortality, heart disease, and stroke. Experts estimate that 130,000 U.S. deaths per year could be saved by improving primary health care access.1 A comprehensive primary health care system delivers accessible and high-quality services that are prevention-focused, integrated with behavioral health care and social services, equitable, and effective.

Primary health care plays an essential role in responding to women’s unique health needs through advanced age and in bridging care during life transitions, from puberty and reproduction to menopause. Achieving the vision of comprehensive primary health care for women is critical to improving health outcomes, bending the cost curve, and promoting health equity.

While women often require care from cardiologists, neurologists, obstetricians and gynecologists (ob/gyns), and other specialists who address particular conditions, these providers may not have the expertise or bandwidth to comprehensively address women’s broad and intersecting health needs across the life course. Therefore, as women age and experience natural life transitions, such as menopause, they require the care and attention of a primary health care provider who can monitor their evolving needs, make connections across specialty services, and understand emerging patterns that may indicate future health risks.2

In the first of two reports, we examine the array of care gaps and structural barriers that inhibit primary health care in the United States from meeting the needs of women of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds. Our findings are based on a review of academic literature, interviews with experts, and an all-day meeting between primary health care innovators and industry leaders. In the second report, we explore existing and emerging care models, technology-enabled solutions, and business approaches that have the potential to close the gaps and barriers in primary health care for women within the next decade.

Why Good Primary Health Care Is So Important for Women

By promoting primary health care for women, we help promote the health and economic well-being of the population as a whole. Studies show that, when a mother dies, her children and her community of family and friends experience a decline in health, nutrition, education, and economic outcomes; they also face a financial loss that may take generations to overcome.3 Given that the rate of maternal mortality is two to three times higher among Black mothers than white mothers, this impact is amplified in communities of color.4

Women also play an indispensable role in the labor force. They make up nearly 60 percent of U.S. workers5 and represent 65 percent of the unpaid workforce of informal caregivers for children, elderly relatives, and family members with disabilities.6 During the COVID-19 pandemic, health care organizations have depended heavily on women, who account for nearly four in five essential health care workers.7 Good primary health care for women is not only vital for promoting economic stability but also critical to limiting costs across the health care system: 90 percent of national health care expenditures are attributed to treating chronic and mental health conditions, both of which significantly impact adult women.8

However, it is clear from our research that the U.S. primary health care system for women is inadequate. Health status indicators show that women in the U.S. have worse outcomes than women in other high-income countries. For example, the U.S. maternal mortality rate is higher than the rate in any other high-income country and continues to rise.9

Staggering disparities persist across women of different socioeconomic, racial, and educational backgrounds. People of color are less likely to receive preventive health services irrespective of income, neighborhood, comorbid illness, or insurance type, and often receive lower-quality care.10 Income inequality also has a profound impact on health; women in the top 1 percent of the income distribution have a life expectancy that is 10 years longer than that of women in the bottom 1 percent, a difference that equates to the health impact of a lifetime of smoking.11 It is paramount for an effective primary health care system to incorporate strategies of caring for low-income populations and address racial/ethnic disparities.

A range of factors contributes to the underperformance of the primary health care system for women. One barrier is the historic “siloing” of reproductive health and maternal health from other key clinical and nonclinical services that are critical to women’s whole health.

Another challenge is the insufficient attention across medical specialties given to sex differences in disease progression and treatment. For example, cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death among women, often presents and progresses differently in women than it does in men.

Similarly, studies have demonstrated notable sex differences in the prevalence of neurological conditions between women and men. Adjusting for age, women are twice as likely to develop multiple sclerosis and two to three times as likely to experience migraines.12 As women have a longer life expectancy than men, they are more likely to experience age-related morbidities, disability, and dementia. For example, as women age, they are twice as likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and are more likely than men to experience strokes that are associated with worse outcomes.13 Despite these differences, commonly used treatment approaches were developed predominantly through research on men and are not as successful when administered to women.14

Gaps and Barriers in Women’s Primary Care

The current primary health care system in the U.S. could be much more responsive to the needs of all individuals, regardless of their sex and gender. But women experience unique challenges when seeking primary health care. Our research identified three categories of gaps and barriers in primary health care (Exhibit 1). In the Appendix, we describe these gaps and barriers in detail and highlight those that are specific to or disproportionately affect women.

A Framework for Transforming Primary Care for Women

The following framework was developed based on findings from the literature review, stakeholder interviews, and convening of experts. It describes a primary health care model for delivering comprehensive, high-quality primary health care that is enhanced for women at all ages and stages of life (Exhibit 2). The model incorporates three types of health care services: those applicable to men and women, those unique to women, and those that women typically experience at different life stages.

Foundational Elements Applicable to Men and Women

Certain characteristics are essential for any comprehensive primary health care system, regardless of its intended patient base. A comprehensive primary health care system must be:

- Accessible, affordable, and accountable to create entry points outside the traditional health system and encourage better consumer engagement.

- Highly integrated across physical health, behavioral health, and social services to serve patients’ needs holistically in a coordinated manner.

- Multidisciplinary, team-based, and highly coordinated with specialty care resources to improve access to and coordination with specialty care when needed and prevent avoidable utilization.

- Prevention-focused and proactive to prevent disease or delay its onset and progression.

- Equitable, culturally competent, and community-driven to respond to patients’ needs and preferences, promote engagement with the health care system, and eliminate disparities.

- Evidence-based so that treatment approaches are tailored at the individual level.

- Enhanced by performance data and seamless technology integration to improve digital access, coordinate care across the care team, and better equip clinicians and patients to make informed decisions.

- Appropriately financed and incentivized to ensure that multidisciplinary primary health care providers — including those who coordinate the provision of social services — are able to meet patients’ needs in a manner that promotes high-value care.

Primary Health Care Domains Unique to Women

The criteria listed above can help primary health care systems optimally serve women of all ages and at all stages of life and deliver care in a manner that accounts for sex- and gender-specific distinctions. Three critical domains include:15

- Sex-specific care: Care related to health needs that are unique to women, such as pregnancy and menopause.

- Sex-aware care: Care for conditions that are diagnosed or treated differently in women as compared to men, such as heart disease and neurodegenerative diseases.

- Gender-sensitive care: Care provided in ways that are inclusive of gender-specific preferences, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA) health needs.

Health Experiences Unique to Women by Life Stage

Primary health care providers should develop sustained relationships with patients across stages of life so they can address or facilitate care for the vast majority of personal health care needs.16 To fulfill this role, primary health care teams, through technology and team-based care, must be organized and equipped to address diverse physical health, behavioral health, and social service needs.17 Based on the specific health experience, primary health care teams may either assume primary or shared responsibility for delivering care:

- Primary responsibility: A broad range of health conditions can be diagnosed and managed cost effectively at the primary health care level, such as prevention and ongoing chronic disease management.

- Shared responsibility: Conditions that cannot be adequately addressed at the primary health care level are managed by specialty, ancillary, and social service providers — including nurses, ob/gyns, and community health workers — with care coordination support from the primary health care system.

Conclusion

The primary health care system is particularly well positioned to play a vital and unique role in addressing women’s diverse physical health, behavioral health, and social needs across the life course. However, major care gaps and structural barriers inhibit the primary health care system in its current form from meeting women’s needs. To optimally serve women of all ages and at all stages of life, the primary health care system must be comprehensive, prepared to deliver sex-specific, sex-aware, and gender-sensitive care, and adept at both managing and coordinating care for an array of health experiences.

In the second of our two reports, we contemplate the concrete steps that policymakers, payers, entrepreneurs, clinical leaders, and investors can take to materially enhance primary health care for women in the next 10 years.

Appendix. Gaps and Barriers in Women’s Primary Health Care

Gaps in Training

Inadequacy of medical education and training addressing gender. Most primary health care training programs do not equip providers to address women’s unique needs. Less than 30 percent of medical schools incorporate gender-specific topics in their curriculum and only 9 percent of medical schools offer women’s health courses or electives.18 Across medical specialties, there is poor awareness of the sex differences in disease progression and treatment and a lack of awareness of pivotal health experiences that women encounter. For example, despite the far-reaching impact menopause has on women’s health, providers are largely ill-equipped to initiate important conversations around this transition with patients.19

Medical training also insufficiently prepares providers to deliver care that recognizes an array of experiences and life paths. For example, though nearly 80 percent of physicians believe addressing social needs is as important as medical care, most do not feel prepared to address them; correspondingly, studies suggest that providers often avoid asking about social issues.20

Did You Know? More than 70 percent of primary health care providers report not feeling well-informed on LGBTQIA health needs and clinical management of LGBTQIA care, and almost 80 percent of primary health care providers are unsure of how and where to refer patients with LGBTQIA-specific needs.21 Many providers assume heterosexuality when interacting with patients, which can cause patient discomfort and deter open communication between patients and providers.22

Barriers to Primary Health Care Utilization

Inconsistent or no regular source of primary health care. Nearly 20 percent of adult women report not having a primary health care provider. This rate is higher among some racial/ethnic minorities, including Hispanic (33%) and American Indian/Alaska Native (26%) women.23

Twenty percent of women consider their ob/gyn to be their primary health care provider, a perception that is more common among women who are pregnant, have newborns, and do not have a chronic condition.24 A recent survey of women between the ages of 18 and 44 found that the majority of respondents were not only more likely to be satisfied with care from their ob/gyn than from their primary health care provider but also were more likely to be open and honest with their ob/gyn than with their primary health care provider.25 This is problematic given that many ob/gyns do not consider themselves primary health care providers and do not offer comprehensive primary health care services.26

Did You Know? Only 20 percent of ob/gyn residencies offer training on menopause, and 80 percent of medical residents report feeling “barely comfortable” discussing or treating menopause.27

Underutilization of primary health care. Recent data indicate that the trend of underutilization of primary health care is worsening. This decline is attributed to a number of factors, including rising out-of-pocket costs, decreased real or perceived needs, and increasing use of some alternative sources of care, such as urgent care clinics.28

Pandemics and other public health emergencies can further exacerbate underutilization. For example, as a result of social distancing orders and other aspects of the response to the COVID-19 outbreak, ambulatory practice visits sharply fell by nearly 60 percent.29

Did You Know? Between 2008 and 2016, primary health care utilization among adults under age 65 dropped by 25 percent; this decline was particularly marked for lower income and younger adults.30

Shortage of primary health care providers. Another major factor is the growing shortage of health care providers to serve a rapidly aging population. The U.S. is expected to see a shortage of up to 50,000 primary health care providers by 2032, with rural areas facing the greatest shortages.31 Though retail health clinics, such as those operated by Walmart and CVS, have the potential to help mitigate these shortages, practice-related regulations and licensing policies may limit their reach in some states.32

Language, culture, and trust. Language and cultural barriers, mistrust, and perceptions that health care providers are not listening to patients’ concerns can deter primary health care utilization and engagement. Multiple studies have shown that higher levels of perceived discrimination and lower levels of trust in the health care system among women from underrepresented communities are associated with lower utilization of preventative and routine services.33

Professional/personal barriers to seeking primary health care. Women are more likely than men to delay self-care as a result of their professional and personal obligations. Caregiving, in particular, has a profound impact on women’s ability to attend to their own health. 60 percent of unpaid, informal caregivers in the U.S. are women.34 Frontline and essential workers battling the COVID-19 outbreak are not only more likely to be women and people of color but also more likely to live at or below the federal poverty line and have children at home, which creates additional and novel burdens with respect to caregiving.35

While caregiving is a challenge across the age continuum, the physical, emotional, and financial burden imposed by this role becomes particularly pronounced when middle-aged caregivers enter the “sandwich generation,” a period during which they may assume simultaneous caregiving responsibilities for young children and aging parents. The burden of this dual role compels the majority of working caregivers to adjust their careers to accommodate caregiving duties and can inhibit them from attending to their own health and well-being.36 For women who balance several roles at home and at work, finding time to go to a primary health care visit during business hours can be a challenge.

Barriers to Delivering Comprehensive Primary Health Care

Time constraints. On average, primary health care visits last 11 to 15 minutes, which is woefully insufficient to gain a holistic understanding of a patient’s medical and social needs, build a relationship of trust to encourage open dialogue, and effectively monitor the specialty, ancillary, and social services that a given patient may be receiving. Shorter visits are incentivized by the typical primary health care reimbursement model, which rewards the number of visits conducted rather than the types of services delivered.

Sex- and gender-based bias. Frequently, women’s concerns are dismissed or perceived as being less severe than men’s. Negative encounters with the health system — from inconvenience to disrespect and abuse — have been shown to suppress a willingness to seek care in the future.37 Notably, clinicians respond differently to women’s reports of pain or discomfort than men’s and observe different treatment practices, such as prescribing sedatives to women and narcotics for men.38 Women are more likely than men to receive referrals to psychologists to address nondescript symptoms and are less likely than men to receive pain medication or interventions. Women who present with heart attack symptoms are often sent home with a diagnosis of stress or panic disorder rather than being given the full cardiovascular diagnostic workup that is more consistently offered to men.39

Did You Know? More than 80 percent of women with chronic pain report experiencing some form of gender discrimination from their health care providers, who may attribute their symptoms to ephemeral diagnoses like “stress” when, in fact, more serious medical conditions exist; moreover, women reporting pain are more likely than men to be prescribed sedatives rather than pain medication.40

Racial/ethnic disparities. Troubling racial/ethnic disparities exist in health outcomes for women of color, including the following:

- Though the rate of breast cancer is similar among Black and white women, the rate of breast cancer mortality is 40 percent higher among Black women. Breast cancer is also more likely to be detected at an earlier stage in white women.41 Latinas are less likely than non-Latinas to receive preventative care, such as regular mammograms and pap tests.42

- The rate of maternal mortality among Black women in the U.S. is two to three times greater than that of white women.43

- Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to lack a usual source of care when sick other than the emergency department, signaling a major gap in access to primary health care.44

- Primary health care practices that serve minority communities tend to be poorly resourced, underfunded, and responsible for serving more medically needy patients compared to clinics that mostly serve white patients.45

- Racial bias has been well documented among all types of health care providers and specialties and is most frequently associated with negative patient-provider interactions.46

- During pregnancy, Black women are less likely to feel that they were encouraged to make their own decisions and more likely to feel pressured into receiving medical interventions.47

Economic inequity. Income inequality and insurance coverage also have a profound impact on health. Women in the top 1 percent of the income distribution have a life expectancy that is 10 years longer than that of women in the bottom 1 percent.48 The rate of screenings, such as mammograms, colon cancer screenings, and Pap tests are lower among uninsured women.49 In states that did not expand Medicaid and have a larger uninsured population, preventable diseases like cervical cancer are more common. For example, in Alabama, which did not expand Medicaid, women who develop cervical cancer have a higher mortality rate than women in other states, in part because women without insurance coverage do not have access to early screenings and care is delayed until the onset of more serious symptoms.50

Inadequate clinical guidelines. Evidence-based guidelines have historically not accounted fully for sex differences in disease progression, in part due to the underrepresentation of women in clinical trials.51 Evidence-based guidelines are particularly inadequate for vulnerable populations, such as women with disabilities. For instance, despite pervasive misperceptions among providers, women with disabilities are equally likely to be sexually active as their peers without disabilities. However, women with disabilities are less likely to be offered information by providers on contraception and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention and are less likely to receive screenings for sexual violence or reproductive cancers.52

Inadequate focus on addressing social determinants of health. Social determinants of health play a particularly salient role in predicting women’s health outcomes. Of the many factors that predict mortality and morbidity, approximately 40 percent are socioeconomic and include education, employment, safety, and income.53 Having at least one unmet social need is associated with increased rates of depression, diabetes, hypertension, emergency department overuse, and clinic “no-shows.”54

The ways in which nonmedical factors impact women’s health can vary by age. For example:

- Factors like financial stability, housing security, nutrition, and exposure to domestic violence during a woman’s reproductive years significantly affect her ability to have a pregnancy free of complications.55

- In the U.S., Black and Hispanic families have a median wealth that is about one-tenth of white families. Disparities in wealth persist regardless of education, marital status, age, or income. Many long-standing factors drive these differences, including systematic labor and mortgage market discrimination.56

- Over one quarter of women ages 65 to 74 and over half of women ages 85 and older live alone.57 As the elderly population continues to rapidly grow, the demand for critical social supports (such as transportation or personal care), as well as interventions to mitigate social isolation, are increasing, yet they are rarely attended to in the primary health care system.58 These needs are likely to be experienced more acutely by older women than older men as women have longer life expectancies.

To address patients’ needs holistically, the primary health care system must address social needs that can serve as barriers to health. While significant new funding and energy is being dedicated to this area, more attention must be focused on developing models that address social determinants of health through community partnerships and integration with primary health care.

Lack of integrated care teams. Primary health care providers are well suited to effectively coordinate care across specialty, ancillary, and social services throughout a woman’s life. Primary health care providers should proactively conduct timely conversations prior to key life transitions and provide warm handoffs to other providers such as ob/gyns, behavioral health specialists, medical specialists, geriatricians, and others across the life course. One of the main factors that inhibits the current primary health care system from serving this role is that integrated, multidisciplinary primary health care teams — typically including physicians, nurse practitioners and/or physician assistants, behavioral health specialists, care coordinators, and social service providers — have not been widely adopted. Practices that have implemented integrated primary health care teams have not done so in a standardized fashion.

Confidentiality and stigma. Confidentiality persists as a major concern that deters women across ages from seeking health care services.

Did You Know? Thirteen percent of sexually experienced adolescents on a parent’s health insurance plan reported not seeking sexual and reproductive health care because of concerns that their parent might learn that they sought care.59 This is particularly significant given that 50 percent of new STIs and over 20 percent of new HIV diagnoses are reported among adolescents and young adults.60

Among adult women, confidentiality is of particular concern in the context of behavioral health. Women ages 18 to 44 are more likely than men to develop a mental illness and are twice as likely as men to develop an anxiety disorder.61 In recent years, the number of women with opioid use disorder at labor and delivery quadrupled.62

However, despite the high prevalence of mental health conditions among women, harmful stigmas endure in the community and in the workplace that discourage women from openly seeking behavioral health services or requesting time off from work for behavioral health appointments.63 Interestingly, when women do seek help for behavioral health needs, they are more likely than men to confide in their primary health care providers as opposed to behavioral health specialists.64

Undersupply of women’s health specialists. Women’s health specialists include primary health care providers with women’s health training, ob/gyns, and medical specialists with women’s health training, including oncologists, cardiologists, psychiatrists, and neurologists. There is great demand for and low supply of key women’s health specialty services. For example, despite the prevalence of behavioral health conditions among women and the fact that the physiological changes associated with pregnancy can significantly impact mental health, some states have as few as one certified, practicing perinatal psychiatrist in residence. Similarly, although an average of 27 million women experience menopause each year,65 studies show that medical residents and practitioners have significant knowledge gaps that inhibit their ability to address menopausal symptoms.66 Though a menopause certification is available to close those knowledge gaps, fewer than 1,000 providers practicing in the U.S. have undergone this special training and are menopause-certified. This paucity of specialists makes it even more crucial that primary health care providers are equipped to offer baseline care for women.

Lack of racial/ethnic diversity among women’s health specialists. Only 5 percent of physicians across medical specialties identify as Black or African American.67 Black women make up just 3 percent of all medical providers.68 Among medical specialties, ob/gyn has the highest number of women and women of color (61.9 percent women and 8 percent Black women).69

Of the members of the American College of Nurse-Midwives, only 7 percent identify as people of color. However, the specialty is becoming more diverse. In 2014, 14.5 percent of nurse-midwives undergoing certification for the first time identified as people of color and 10.3 percent of midwifery students identified as Black.70

Lack of comprehensive primary health care and digital innovations. Although a wave of novel care models and digital solutions have emerged in recent years that have the potential to address discrete gaps in today’s primary health care system for women, no single innovation or validated combination of innovations comprehensively addresses women’s physical health, behavioral health, and social needs. Emerging innovations that could materially improve access to care, such as telehealth/telemedicine technologies, have not been uniformly adopted by primary health care practices and cater largely to commercially insured populations in their present form.

One much needed digital innovation is integrated and longitudinal electronic health records (EHRs). Effective longitudinal EHRs present a comprehensive snapshot of each patient’s medical and social needs, and can facilitate early diagnosis, reduce errors, and support better patient outcomes.71 However, there is significant room for improvement to ensure that EHRs effectively advance health care delivery. A recent study revealed that some primary health care physicians spend more time documenting in their EHRs than providing clinical care.72 Forty percent of primary health care providers feel that EHRs present more challenges than benefits, and nearly 60 percent feel that significant improvements are required to derive clinical value from EHRs.73 According to primary health care providers, some of the key improvements that must be made to EHRs over the next decade include improving interoperability, enhancing predictive analytics, integrating financial information and data on social determinants of health, and enabling patients to access and share their own records.74

Did You Know? As of May 7, 2020, all states plus Washington, D.C., have issued guidance to expand the use of telemedicine in their Medicaid programs during the COVID-19 pandemic.75

Underrepresentation in Health System Leadership and Policymaking

Lack of gender and racial/ethnic diversity across industry leadership and academia. Though the presence of women in leadership and decision-making roles across the health care industry is slowly increasing, women are still significantly unrepresented as compared with men. As of 2018, only 4 percent of CEOs and 21 percent of board members of Fortune 500 health care companies were women.76 Hospital leadership in 2019 demonstrated slightly better gender diversity, with women assuming approximately 37 percent of leadership roles;77 however, only 16 percent of deans and department chairs at academic medical centers are women.78

Inadequate gender diversity in both the health care industry and academia is further compounded by limited racial/ethnic diversity. In 2015, 91 percent of all hospital CEOs were white.79 Nationwide, over 60 percent of full-time medical faculty are white, 20 percent are Asian American, 5 percent are Hispanic, and less than 4 percent are Black.80 Across medical school faculty, the proportion of female faculty members decreases as the faculty rank increases in seniority; this is particularly pronounced among non-white women.81

While several female-focused and female-led companies recently launched, new primary health care startups tend to have largely male leadership. Notably, in 2019, only 12 percent of partners at venture funds active in digital health were women. Improving gender diversity is inherently beneficial to health care businesses; one study demonstrated that diverse management teams are more innovative and generate 19 percent higher financial returns.82 As new primary health care models emerge and seek venture capital support, it will be critical to promote gender diversity among investors to ensure that investments are directed towards women’s health-focused companies. Male venture partners tend to back women’s health companies very infrequently and often overlook the issue of gender diversity when evaluating potential investments.

Politicization of Women’s Health

Women’s reproductive health across the life course is highly politicized. The harmful stigmas that result can deter women’s willingness to seek health care on a regular basis, discourage open dialogue between women and their physical and behavioral health care providers, and profoundly impact long-term health and well-being.

The impact of politicization is most acutely felt by lower-income women, who disproportionately rely on publicly funded health care coverage and, therefore, have fewer options for receiving comprehensive women’s health services.83 For example, enrollment in Texas’ family planning program decreased by 25 percent after the state prohibited the participation of providers who offer comprehensive reproductive health services, including birth control and abortion, in the program. This decrease in access to comprehensive reproductive health care was associated with a 26 percent increase in the birth rate among Medicaid enrollees and a spike in the number of teen pregnancies.84

Did You Know? Eighteen states impose abortion-related restrictions on the allocation of public funds for health care. Nine states restrict federal Title X family planning funds from being used to reimburse providers who perform abortions and/or offer counseling on reproductive health. Fifteen states prohibit state funds from financing providers who perform abortions and/or offer counseling on reproductive health, and 12 states restrict public funding for STI testing and treatment as well as sex education.85 In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, state officials in at least nine states have classified abortions as elective procedures and have taken measures to stop performing these interventions during the public health emergency, despite the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidance that abortions are essential and time-sensitive.86

How We Conducted This Study

Manatt Health reviewed current academic literature on primary health care and conducted interviews with 15 multidisciplinary industry leaders and subject matter experts representing innovators, payers, health systems, and academia. Learnings from this preliminary investigation informed a robust, all-day meeting in December 2019 that the Commonwealth Fund convened with 17 innovators and national experts on opportunities to transform primary health care for women. The convening participants were selected for their deep expertise, the breadth of organizations they represent across the health care industry, and their professional and personal perspectives on primary health care for women. See the Acknowledgments for a complete list of individuals who contributed to this work.

Acknowledgments

The Commonwealth Fund

- Yaphet Getachew, Program Associate

- Corinne Lewis, Senior Research Associate

- Eric Schneider, Senior Vice President for Policy and Research

Convening Participants

- Adimika Arthur, HealthTech for Medicaid

- Sydney Etheredge, Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Seth Feuerstein, Yale School of Medicine

- Ann Garnier, Lisa Health

- Margaret Laws, HopeLab

- Debra Ness, National Partnership for Women and Families

- Neil Patel, Iora Health

- Ileana L. Piña, Wayne State University/American Heart Association

- Christine Ritchie, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Evan Schnur, Walmart

- Lisa Simpson, AcademyHealth

- Leah Sparks, Wildflower Health

- Emily Stewart, Community Catalyst

- Deneen Vojta, UnitedHealth Group

- Jane Weldon, CommonSpirit Health

Stakeholder Interview Participants

- Molly Coye, Executive in Residence, AVIA

- Joia Crear Perry, National Birth Equity Collaborative

- Susan Edgman-Levitan, Executive Director, John D. Stoeckle Center for Primary Care Innovation, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Mary Langowski, Founder and CEO, Rising Tide

- Emily Maxson, Chief Medical Officer, Aledade, Inc.

- Sharon Vitti, Senior Vice President and Executive Director, CVS Health/MinuteClinic

- Jeanette Waxmonsky, Vice President Integrated Care, Product Development at New Directions Behavioral Health

- Elizabeth Yano, Director, VA Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy

Manatt Health Subject Matter Experts

- Jocelyn Guyer, Managing Director, Manatt Health

- Brenda Pawlak, Managing Director, Manatt Health

- Carol Raphael, Senior Advisor, Manatt Health

- Edith Coakley Stowe, Director, Manatt Health

- Sharon Woda, Managing Director, Manatt Health

Graphic Recording

- Sasha Brito, ImageThink