The goal of universal coverage depends on moderating health care costs, which will require overcoming the unjustified variation and inflationary rise in the prices of care, including drug prices. To gain insight into these challenges — and opportunities — it may be instructive to look at pharmaceutical assessment and pricing in Germany. Germany’s health insurance system shares many characteristics with that of the United States, yet the country has lower drug prices, as well as prices that are more directly linked to clinical benefit.

Prices for new drugs are established in Germany through collective negotiations between a single buyer (the umbrella organization representing the insurers, also known as the Sickness Funds) and a single seller, the drug maker. Given this bilateral monopoly, one might predict gridlock, with insurers insisting that high prices threaten the solvency of the system and manufacturers insisting that low prices threaten innovation.

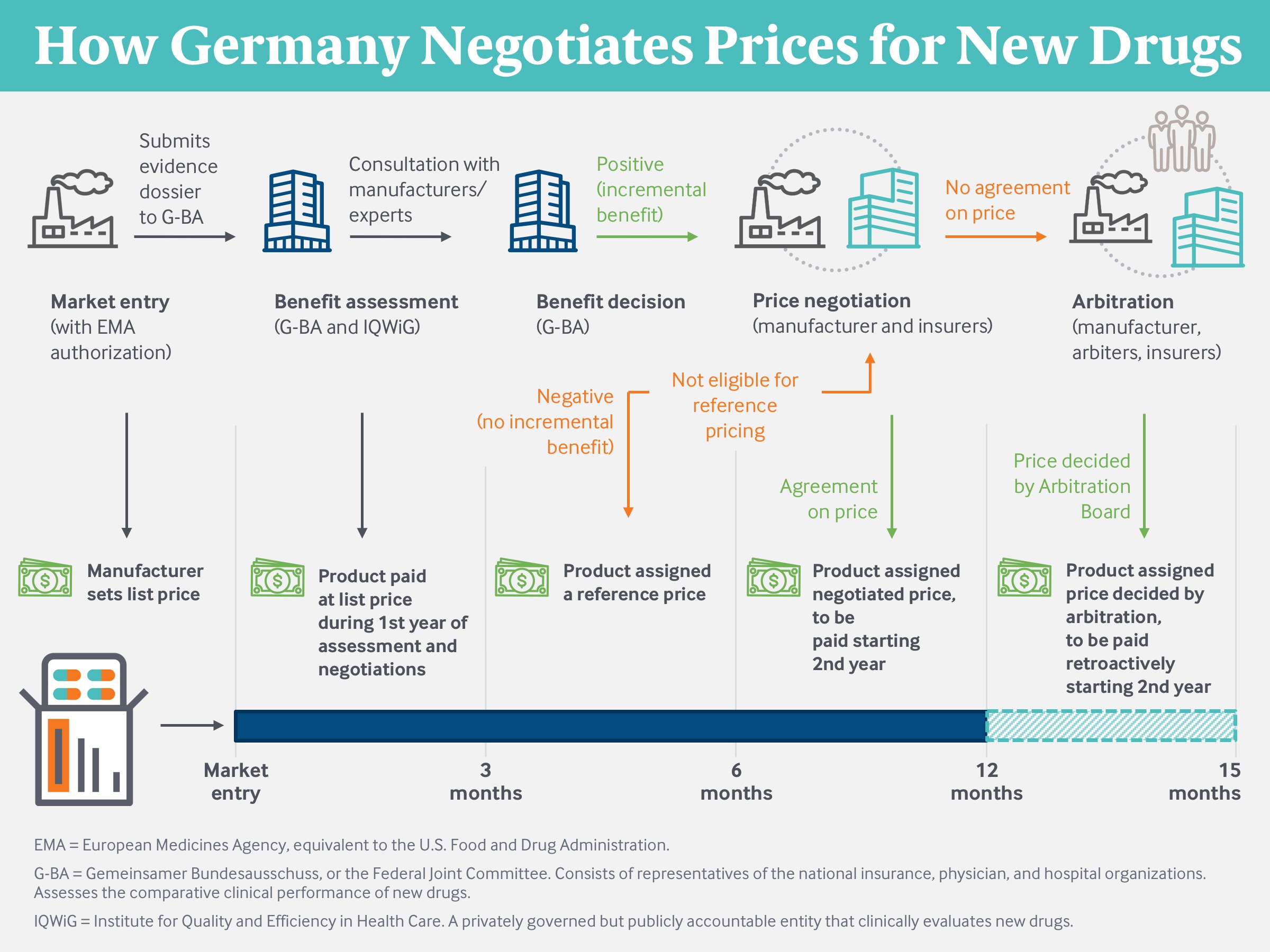

However, both sides are under strong public and political pressure to come to an agreement. If none can be negotiated, the drug’s price is established by an arbitration panel with representatives from each side plus an appointed chair. The manufacturer can refuse the arbitrators’ price and withdraw its product, but then forgoes all sales in the continent’s largest market and knows it will enter price negotiations for its next drug with a reputation for being uncooperative.

From 2011, when this price structure was established, to mid-March 2019, the German pharmaceutical system has conducted assessments and pricing for 230 drugs. Of these, 35 drugs had a price set by arbitration and 28 were withdrawn from the market by their manufacturers.

Manufacturers can withdraw their product from the German market if the resulting price is so low as to undermine prices that can be charged elsewhere. In practice, manufacturers continue to see the German market as important and financially attractive and have not withdrawn any drugs that were shown to offer incremental clinical benefit over their closest comparators.

A unique feature of the German system is that the final negotiated and arbitrated prices are not confidential. Numerous other nations reference the final German prices when administering or negotiating their own rates. The Trump administration has proposed an analogous system of international reference pricing to cap rates paid for physician-administered drugs under Medicare Part B.

Generic drugs and biosimilars are assumed, by definition, not to offer incremental benefits over comparator products. In most cases, they are assigned to therapeutic classes subject to reference pricing, along with new drugs found not to offer incremental benefit. Some Sickness Funds negotiate supplemental rebates for generics and biosimilars as a condition for favorable treatment in their utilization management programs.

Source: Modified from Techniker Krankenkasse (2019).

The outcome seems positive from the perspective of German purchasers. Drug prices in Germany tend to be at the high end of the range for European nations but substantially below U.S. levels. This difference isn’t solely because of the centralized assessment and negotiation structure, since even prior to 2011 manufacturers were required by regulation to offer rebates off list prices. Prior to 2011, all drugs faced the same mandated percentage rebate. Now discounts are large for drugs that offer little or no incremental benefit but small for drugs where the Federal Joint Committee (GBA) find a meaningful contribution to patients’ health.

This process is widely accepted both politically and socially and is largely free of the vitriol so prevalent in the U.S. drug-price debate. Sickness Funds are not accused of “rationing,” or denying coverage for important treatments. Pharmaceutical firms are not accused of “gouging,” or charging more than the health care system can afford to pay. There seems to be consensus that drug prices must be high enough to finance innovation but low enough to sustain affordability, and that prices for innovative drugs should be higher than those for less innovative products.

Could the U.S. incorporate some of these processes without violating deeply embedded institutional and cultural tenets? To do so would require the U.S. to assess the incremental clinical benefits of new drugs and use that information to negotiate prices.

Assess the incremental clinical benefit offered by each new drug in comparison to alternative treatments.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers currently conduct clinical efficacy studies for the Food and Drug Administration and the equivalent agency in Europe, and comparative effectiveness studies for the GBA. U.S. payers rely on FDA-mandated studies for clinical effectiveness but conduct their own back-of-the-envelope economic assessments when deciding whether and how to include a drug on their formularies. They should follow standardized methods established by a credible third party; open their processes to input from patients, physicians, and other stakeholders; and be transparent with the results.

Use these clinical assessments to negotiate drug prices.

The private Institute for Clinical and Economic Review performs clinical assessments on a voluntary basis. These assessments are used by some payers and manufacturers in price discussions. Many U.S. insurers and pharmacy benefit managers have enrollments comparable to the entire population of European nations. They already have sufficient scale to negotiate in a meaningful way for prices that are aligned with clinical value.

Success for a drug-purchasing system would include three features: a transparent and evidence-based approach to evaluating the clinical value of each new treatment; an affordable set of prices linked to clinical value; and a recognition by both buyers and sellers that the process is fair, financially sustainable, and supportive of continued investments in pharmaceutical innovation. The German system seems to be achieving all three, and could have important lessons for the United States.