During February’s State of the Union address, President Trump touted his administration’s efforts to expand access to short-term health plans that do not comply with any of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) consumer protections. Short-term plans are often cheaper than ACA-compliant plans because they can deny coverage to people with preexisting health conditions, impose higher cost-sharing, and exclude entire categories of services. Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which amends Medicaid to create a state option for providing COVID-19 testing and related visits for the uninsured, Congress defined people with short-term plans as being among the uninsured.

Advocates of short-term plans argue that they provide sufficient coverage for catastrophic medical situations, such as COVID-19. But while recent federal guidance requires private health insurers to cover COVID-19 testing and cost-sharing for related services, this requirement does not extend to short-term plans, which claim to be covering some costs but not all.

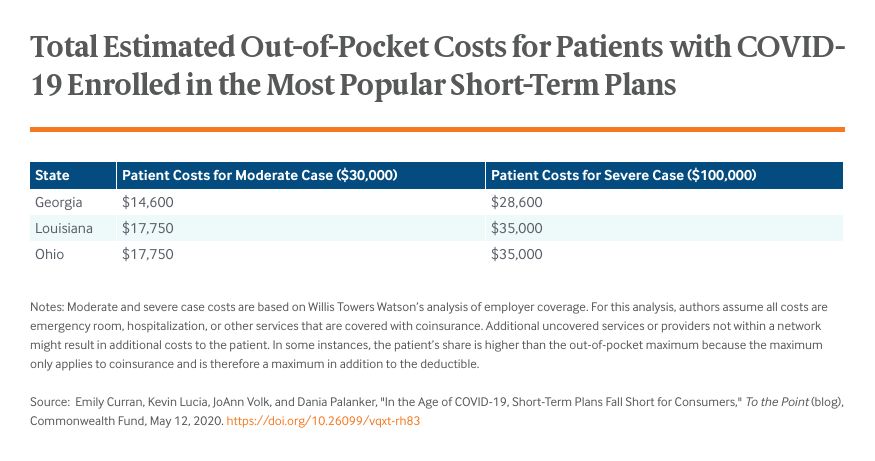

We reviewed plan brochures for 12 short-term plans currently being sold in Georgia, Louisiana, and Ohio and found that people enrolled in them have less financial protection if they need treatment for COVID-19 than people enrolled in ACA plans.

People in Short-Term Plans Likely to Face Coverage Gaps, High Out-of-Pocket Costs, and Nonrenewal

Risks of Coverage Gaps and High Cost-Sharing for Medically Necessary Care

Short-term plans often have major coverage gaps that would extend to COVID-19-related services. Of the 12 short-term plans reviewed, 11 excluded nearly all coverage of prescription drugs, with some providing limited coverage of inpatient prescriptions. At least one plan in every state excluded preventive care like immunizations and most noted that any form of experimental treatment would not be covered, which could include drugs like hydroxychloroquine and remdesivir that are not yet approved or for routine use in treating patients with COVID-19.

Even when services are covered, short-term plans often impose high cost-sharing. Nine of the 12 plans had deductibles of $10,000 to $12,500. COVID-19 patients who require treatment need to pay these amounts before any coverage begins, except in rare instances where some cost-sharing for COVID-19 testing and treatment may be waived. These patients also may be required to meet separate deductibles specific to ER treatment, which we observed in 10 plans. One plan in Louisiana requires consumers who need ER care to first meet a $500 ER deductible, then the plan’s $12,500 deductible, then 30 percent coinsurance. Half the plans set their out-of-pocket maximum at $20,000 or more for a six-month period. Since the deductible does not count as part of the maximum, consumers may be left with $30,000 or more in bills for covered in-network services in the worst situations.

Coverage Denied Because of Preexisting Conditions

Every plan reviewed had a policy stating that there is no coverage of services related to preexisting conditions. This was often broadly defined to include a condition that was not necessarily diagnosed but produced symptoms that would have caused an “ordinarily prudent layperson” to seek medical advice or treatment. Therefore, although this strain of COVID-19 is novel it is likely to be considered a preexisting condition if a consumer was infected prior to purchasing the short-term plan.

Risk of Balance Billing

Experts suggest the risk of receiving an unexpected medical bill from an out-of-network provider during an emergency or hospital stay is greater under short-term plans because most do not have an established network of contracting providers. Short-term plans often pay what they deem “reasonable and customary,” even though it can be thousands of dollars less than the actual bill and provide enrollees no protection above that amount. Providers who charge more than the short-term plan’s set rate will bill the patient for additional payment, leaving them with even higher medical bills.

Deceptive Short-Term Marketing Persists Even During COVID-19 Crisis

Consumers may not understand the limitations of these policies because of deceptive marketing. In one study, consumers shopping online for comprehensive coverage were directed to short-term plan websites, which often failed to provide sufficient information on exclusions, including those for preventive health care like vaccines. State regulators have warned consumers of deceptive marketing after seeing an increase in robocalls selling non-ACA-compliant plans over the phone without explaining policy limits. Even in a global pandemic, concerns about aggressive and deceptive marketing persist: researchers recently found that brokers selling short-term policies provided false and misleading information about coverage for COVID-19.

Looking Forward

As consumers seek health coverage during the coronavirus pandemic, policymakers should consider whether short-term plans will meet their needs. Our review of current short-term plans shows that their limitations could be especially problematic for people who become ill and need care for COVID-19. Twelve state-based marketplaces have already announced they will offer a special enrollment period for residents to access ACA-compliant coverage, although the Trump administration has not granted consumers a similar opportunity on the federal marketplace. States, which have broad authority to regulate short-term products, can prohibit the marketing of such policies during the crisis or require them to cover testing and treatment of COVID-19 without cost-sharing. At a minimum, regulators should ensure that short-term plan insurers do not use deceptive marketing tactics to target the newly uninsured.