Lewis J. Kaplan, M.D., the newly elected president of the Society of Critical Care of Medicine, is guiding efforts to prepare surgeons, anesthesiologists, and physicians of other disciplines to help care for critically ill or injured patients if and when demand for intensive care services for COVID-19 cases exceeds local capacity. The organization’s 16,000 members — who include physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses, pharmacists, and respiratory therapists among other professionals — are also spreading the word about the organization’s free training materials for frontline providers. The Commonwealth Fund asked Kaplan, a general, trauma, and critical care surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, how we can better prepare for surges in coronavirus cases.

Commonwealth Fund: You’ve heard from a wide range of specialists, from plastic surgeons to ophthalmologists, who are willing to step in to help treat patients suffering from complications of COVID-19. Is it possible to ballpark the number of additional hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) staff we might need to meet demand in different locations?

Kaplan: It’s a very complicated calculus, because so much depends on local circumstances. If you looked at New York, or New Orleans, or Philadelphia, or Atlanta, you would have very different estimates for each. The key metric is how many people need mechanical ventilation. To know that you need to know: How old is the population? Do they routinely use health care? Are you located near a quaternary care center, where there is an enormous transplantation population, or a grouping of patients with cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease? Is there a big indigent population that has lacked access to preventive care? It’s all those things plus individual genetics. The number of hospital ventilators also dictates the number of staff.

Commonwealth Fund: What is your view of the adequacy of the nation’s supply of ventilators?

Kaplan: Some hospitals are seriously stressed and some are not. We are working hard to locate additional ones that are not in use in ambulatory surgery centers, medical schools, and even veterinary clinics and large animal labs. We have a lot of ventilators for anesthesia in the U.S. — some 70,000 — and anesthesiologists and nurse anesthetists who can operate them.

Commonwealth Fund: How might health system and government leaders organize the inventory and distribution of ventilators and other crucial ICU equipment to ensure it reaches communities that are short?

Our free trainings won’t make a clinician into an intensivist, but it can help bridge the gap between their current knowledge base and what they may need right away to save someone’s life.

Kaplan: I was on a call with the White House recently where we discussed creating a national dashboard, so that we would know, in one hospital or in one city, how many beds there are, how many are occupied, and how many have patients on invasive ventilation and noninvasive ventilation. If you had those numbers, the computing power of the National Laboratories could take that, assess region by region what has been happening, and then interface that with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response and the national health care disaster preparedness plan. Some of this information is now collected by FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] and some by CMS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services], but it’s not quite there the way we need it.

Commonwealth Fund: Assuming we can get ventilators to the places that need them, what sort of training do non–critical care specialists need to step in and what is the society offering them?

Kaplan: We are taking a two-pronged approach to education. The ICU professionals need highly technical information about diagnosis and the approaches used in different countries and for different types of patients. We’re also providing information on getting non-ICU staff up to speed on using ventilators and managing large populations of patients in disaster scenarios. Whether you come frontloaded with experience in pulmonary disease management or chronic kidney disease, everyone has something to bring, whether it is a cognitive skill set, a hand–eye coordination physical skill set, or just the capacity to lead. I want people who are willing to take care of patients. And that is everyone in medicine; that’s why we went into it.

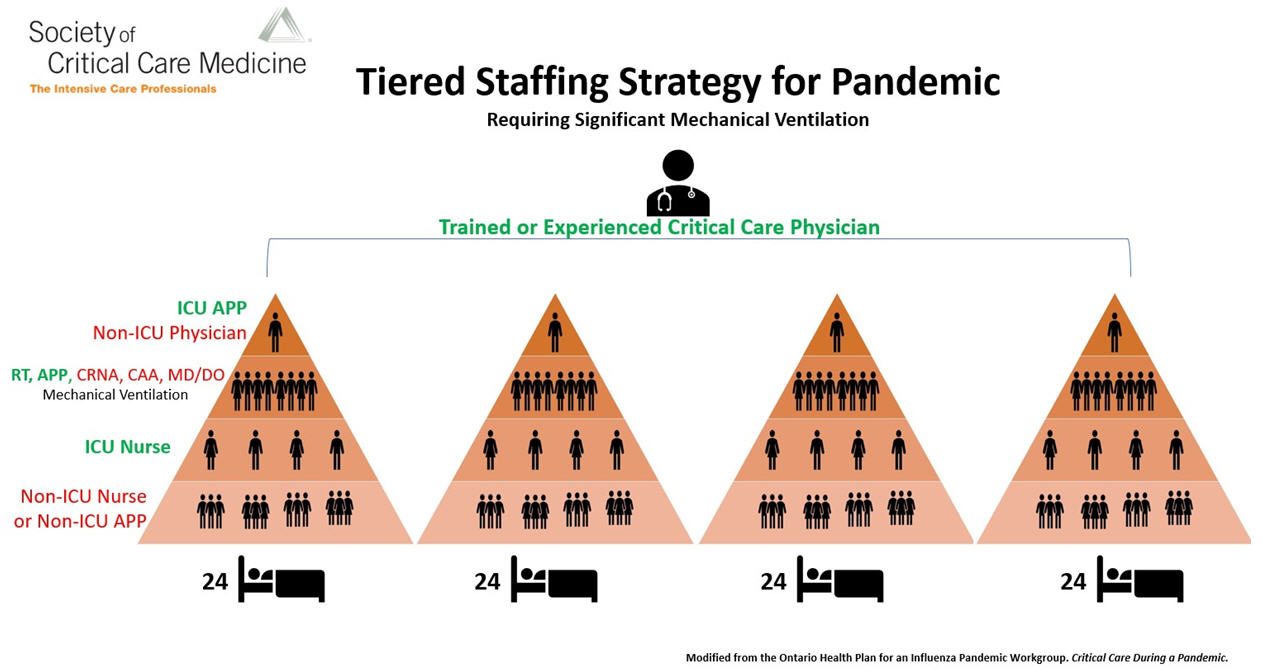

Note: In the crisis model presented here, a physician who is trained or experienced in critical care and who regularly manages ICU patients, oversees the care of four groups of 24 patients each. A non-ICU physician (eg, anesthesiologist, pulmonologist, hospitalist), who ideally has some ICU training but who does not regularly perform ICU care, is inserted at the top of each triangle. This non-ICU physician extends the trained or experienced critical care physician’s knowledge, while working alongside APPs who regularly care for ICU patients. Similarly, to augment the ability to mechanically ventilate more patients, experienced ICU respiratory therapists and APPs are amplified by adding clinicians such as physicians (either MD or DO), nurse-anesthetists, and certified anesthesiologist assistants who are experienced in managing patients' ventilation needs.

Commonwealth Fund: Of the changes being made by health system leaders as well as state and federal policymakers in response to the pandemic, which do you think are here to stay?

Kaplan: I think we will all have more stock of things — not just ventilators but also personal protective equipment. I think you’re going to find protocol-sharing across health systems to a much greater extent than before. But what I really hope happens is that there is intense federal activity around information-sharing about how to manage infectious diseases in major metropolitan areas. If you think about what they did in China, it was remarkable.

Commonwealth Fund: Building a hospital in 10 days?

Kaplan: Yes, that, but they also did something else: they took clinical staff and supplies and devices and moved them where they needed to go. I think we’re going to need a variation of this in every large city in this country. I envision taking a giant abandoned building and having the Army Corps of Engineers make it structurally sound, pipe it, and wire it in a modular fashion, so that in the case of something like this that building becomes the infectious disease facility. It could be filled in a modular fashion with contributions from the major medical institutions. That way, hospitals can continue to see patients without disrupting their operations.

That kind of novel thinking is a very different way to prepare for these kinds of things. We’ve never had to do that before, but now we have been caught, and we won’t let ourselves get caught like that again.

Have you changed the way you work in response to COVID-19? We’re interested in hearing from you; contact Martha or Sarah.