The number of Americans struggling with mental health issues has increased significantly since the outbreak of COVID-19. Fears about the virus and concerns about the future, as well as job loss, economic insecurity, and social isolation, are contributing to depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues. In a survey conducted in April, 13.4 percent of adults 18 and older reported symptoms of serious psychological distress, compared with 3.9 percent in April 2018. Deaths from suicide and alcohol or drug misuse are also projected to increase by an additional 75,000 before the economy recovers from COVID-19.

States face a major challenge to ensure that mental health needs are being met — both for people whose care was disrupted and for people with new mental and behavioral health needs brought on by the pandemic. While no state has yet provided a comprehensive response, all have implemented measures to address the issue, providing a wealth of ideas and promising practices. These strategies largely fall into five categories: telemental health, licensure and scope of practice, insurance changes, establishment of new services, and visibility and durability of efforts.

Strategy 1: Expanding Access to Telemental Health Services

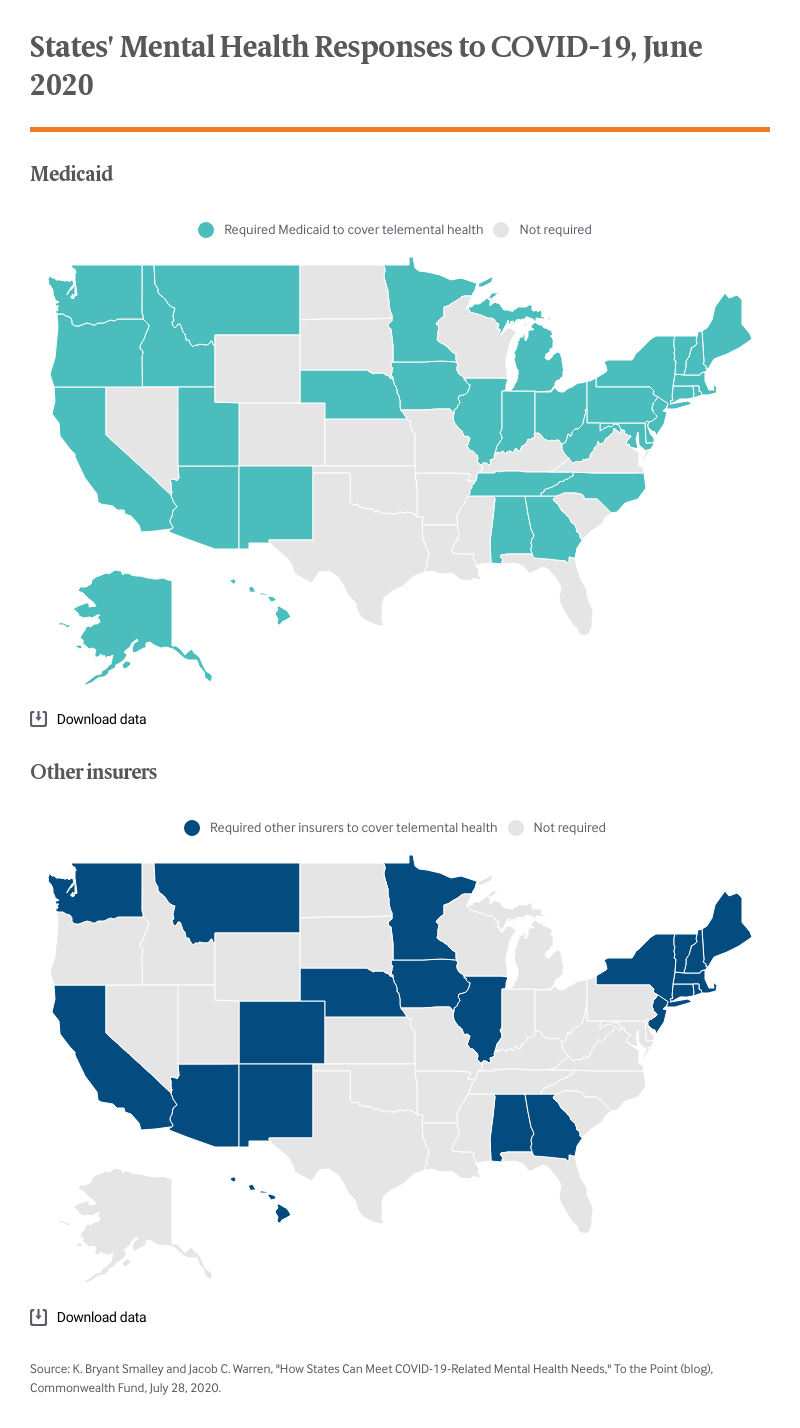

The most widely used strategy has been telehealth, a critical avenue for addressing mental and behavioral health needs during the pandemic. Thirty-three states directly or implicitly required Medicaid plans to cover telemental health services through emergency orders. States that did not require coverage were predominantly those that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act: 10 of the 14 nonexpansion states did not require Medicaid to cover telemental health services.

While requiring Medicaid to cover telemental health assists individuals in the safety net, it leaves out people covered by private insurance; many such insurers do not cover telemental health services and, to date, only 21 states have required private insurers to do so. While all 36 Blue Cross and Blue Shield insurers expanded telehealth coverage at the beginning of the pandemic, they did so in a time-limited fashion. It is unclear if such coverage will continue throughout and after the pandemic. The availability of coverage is even less clear among self-insured employer plans. While high-deductible self-insured plans have been allowed to offer telehealth services without a deductible through 2021 due to the pandemic, guidance from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Health and Human Services Office of Civil Rights does not apply to self-insured plans.

In addition to insurance changes, many states used emergency orders to reduce barriers to telehealth treatment of behavioral health problems. For example, Arkansas suspended its prohibition of telephone-based mental health treatment; Alaska specifically allowed for remote examination, diagnosis, and treatment of opioid use disorder; and Maryland implemented coverage for behavioral health encounters that do not involve live interaction (for example, via email).

Strategy 2: Relaxing Licensure Requirements and Expanding Scope of Practice

A frequently cited barrier to expanding mental health services is restrictive, state-based licensing requirements and scope of practice regulations. As with physician licensure, psychologists and other therapists typically must establish licensure in each state where they would like to practice. Similarly, many states do not include certain licensures (such as licensed professional counselors) within their reimbursement policies or do not allow certain encounters (e.g., medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder) to take place via telehealth.

Several states targeted these barriers in their responses. West Virginia removed the requirement that people receive counseling to receive opioid use disorder medications and Nebraska issued an executive order expediting licensure for mental health providers.

Strategy 3: Modifying Insurance Law and Coverage

States also took actions to leverage insurance law to expand access. For instance, Florida amended its state employee health plans to cover telemental health services, New Jersey directed managed care providers to reimburse providers for telemental health, and Rhode Island eliminated copayments for telephone-based services. Such changes can have an immediate impact on large segments of the population.

Strategy 4: Establishing New Services or Expanding Support for Existing Services

Several states established COVID-19 mental health hotlines for specific groups, including frontline workers (Nevada), mental health professionals and essential workers (Oregon), and the general public (Texas). Other examples of new or expanded support include Wisconsin establishing an outreach and substance use disorder recovery program for homeless veterans and Minnesota creating telehealth alternatives to replace school-based mental health services for children and their families.

Strategy 5: Enhancing Visibility and Durability of Services

States’ efforts not only raise awareness of available mental health services, but also seek to eliminate the divide that often occurs between physical and mental health services. The governor of Missouri held a press conference focused on the importance of mental health during the pandemic, Michigan created a racial disparities task force that included a charge to remove barriers to accessing mental health care, and California created extensive pandemic guidance for behavioral health programs.

Where to Go from Here

States have engaged in remarkable levels of innovation during the pandemic to ensure residents’ mental health needs are met. State policymakers have an opportunity to continue such innovation by learning from their peer states. But states can also take steps to protect the advances made over the past several months. If innovations put in place are not codified in some way, they will expire with their associated emergency declarations. Utah has been leading the way, indicating that some emergency actions, such as coverage for telephone-based mental health services, will be permanent. Following Utah’s lead will ensure people have access to needed mental health services.