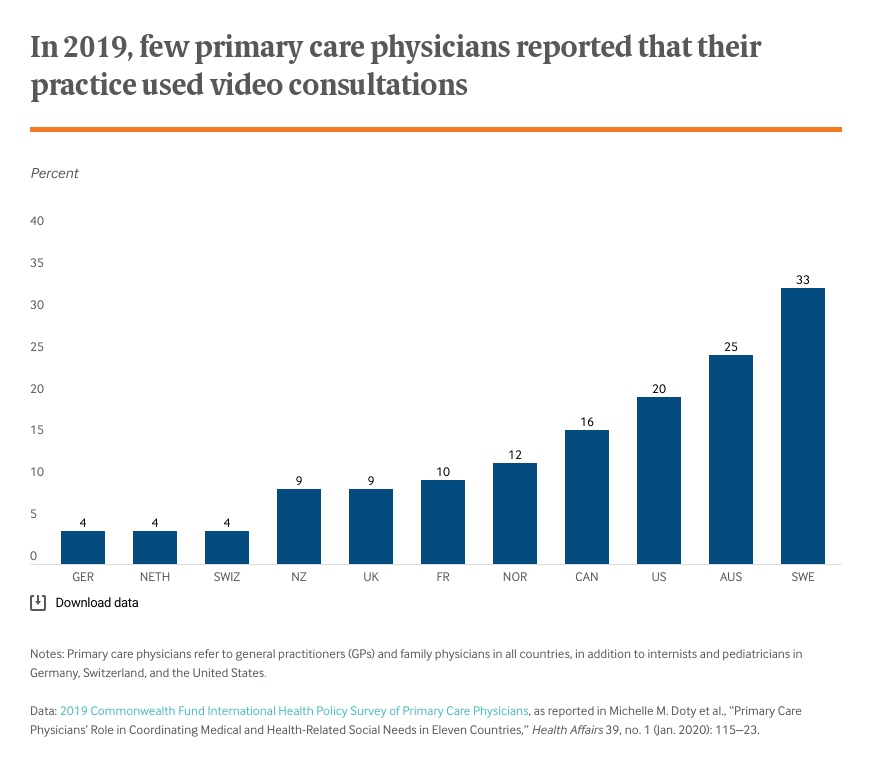

Telemedicine use has expanded dramatically in many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling providers to safely triage and treat patients with milder cases of the disease, as well as patients with chronic medical or behavioral health needs. Before the pandemic, many primary care providers reported never conducting a video consultation, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s 2019 International Health Policy Survey.

To understand how telemedicine use varies across countries and what its future may hold, we turned to Tiago Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi, Ph.D., a health policy analyst at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Oliveira Hashiguchi, who studies digital transformation in health care, authored an OECD study on telemedicine published in January, just as the novel coronavirus began making headlines worldwide.

Commonwealth Fund: Just to get us started on the same page, how do you define telemedicine?

Oliveira Hashiguchi: That’s an important question. There is no single widely used definition of telemedicine. We define telemedicine as the use of information and communication technology — including computers, communications equipment, and software — to deliver clinical care at a distance.

Commonwealth Fund: Okay, so what are the top takeaways from your study of what’s driving telemedicine use in OECD countries and the impact it’s had so far?

Oliveira Hashiguchi: We found that most OECD countries had some form of telemedicine in place before the COVID-19 pandemic. But policies varied widely in terms of the types of telemedicine allowed, the funding and payment approach, eligibility for participation of health care workers and patients, and the integration with traditional face-to-face services.

We found this variation most pronounced in the types of services delivered via telemedicine and their format — whether services are provided in real time, asynchronously, or through telemonitoring — with provider payment and patient cost the major drivers of use. If reimbursement for telemedicine services is limited to specific uses, such as telestroke in Slovenia or cardiac rehabilitation in Poland, we can expect that only those services will be provided, and at relatively small scale.

One exception is teleradiology [the electronic transmission of radiological images for interpretation and consultation]. Before COVID-19, teleradiology was already well established at the national level in most OECD countries. Most other telemedicine programs are smaller-scale and tend to focus on a specific specialty, health problem, or patient population.

Commonwealth Fund: What can you tell us about the characteristics of countries that have been able to use telemedicine most effectively during the pandemic?

Oliveira Hashiguchi: Our COVID‑19 OECD Health System Response Tracker offers some good illustrations. Some countries acted quickly to scale up telemedicine use by passing new legislation, as in Peru and Costa Rica, by expanding insurance benefits to include telemedicine, like in Estonia and Belgium, or by allowing new services including eprescribing and electronic sick leave certificates. Other countries lifted requirements, such as a mandatory face-to-face encounter prior to being seen virtually.

While these changes have led to significant increases in the number of telemedicine services provided, structural barriers to wider use are harder to tackle in a short time frame. These include problems of interoperability, lack of technology infrastructure, limited digital health literacy among patients and providers, and connectivity issues, among others.

Countries that started tackling these challenges before the pandemic were naturally better positioned to quickly scale up use during the crisis. South Korea, for example, had relatively limited use of telemedicine before the pandemic but was able to rapidly expand services because internet access and broadband use are nearly universal.

Commonwealth Fund: Have you seen new uses of telemedicine that you would not have anticipated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Oliveira Hashiguchi: I have not yet seen new, unanticipated uses of telemedicine. But the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly brought about significant developments in existing applications, as well as in use of telehealth or employing technology for purposes other than providing direct clinical care. These include the use of artificial intelligence to handle hundreds of simultaneous requests for information in multiple languages; larger academic medical centers providing real-time emergency support to community hospitals; use of robots to minimize physical contact in hospital wards; and use of remote monitoring tools such as wearables to collect timely data from COVID-19 patients.

Recent months have unequivocally demonstrated that many telemedicine services are not only feasible but can be quickly implemented and scaled. At the same time, this crisis illustrates the limits of remote care. A large share of medical services, including surgical follow-up and imaging in prenatal care, can’t be done in virtual fashion. I expect with time, especially with younger digital natives coming of age, many health care services will be virtualized, but there will always be a need for face-to-face care.

Commonwealth Fund: You note that in exploring the use of telemedicine, providers often hit a wall of regulatory uncertainty, patchy financing, and vague governance. What guidance would you give policymakers about promoting the appropriate use of telemedicine going forward?

Oliveira Hashiguchi: Some barriers to wider use have already been targeted in policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, including creating new payment schemes for telemedicine services and lifting some regulatory restrictions. Going forward, policymakers in local and central governments could focus on clarifying medical liability and jurisdiction, such as by harmonizing licensure requirements across jurisdictions and providing guidance to physicians on conducting teleconsultations. They also could invest in infrastructure and connectivity, particularly in rural areas; promote digital health literacy and awareness of digital risks to providers and patients; and experiment with regulatory models that support innovation, like the Sandbox in Singapore.

Policymakers also can promote a transition to learning health care systems in which evidence is both developed and applied as a natural product of the care process. Policymakers in countries where telemedicine services are most advanced enable the spread of best practices through knowledge aggregation, transfer, and dissemination. We also see that successful telemedicine interventions tend to emerge from health care providers seeking to improve care locally. But for local innovations to spread, it’s necessary for countries to identify and disseminate best practices that are also aligned with national priorities.

The views expressed here are those of Tiago Cravo Oliveira Hashiguchi and do not necessarily represent the views of any OECD country.