Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, musing about the Court possibly overruling Roe v. Wade, asked, “If people actually believe that it’s all political, how will we survive? How will the Court survive?” Recent cases brought by Republican state attorneys general before Republican-appointed judges who have temporarily blocked vaccine mandates raise the same question.

Federal COVID-19 Vaccine Mandates

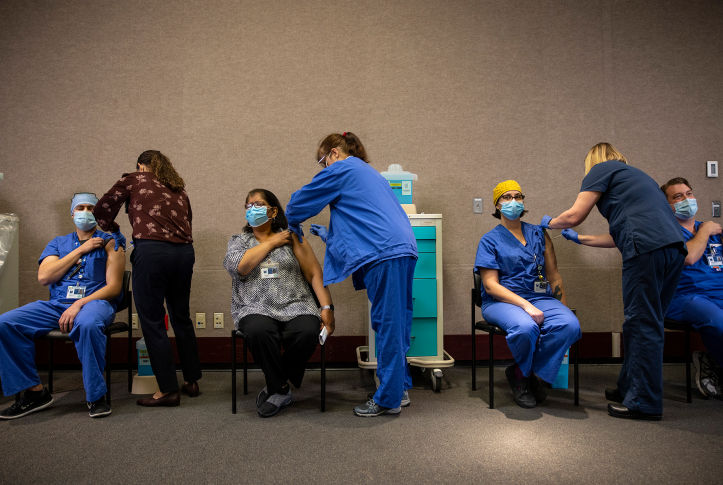

As COVID-19 infections increased this fall, the federal government issued several vaccination mandates. This is not surprising: vaccines are proving effective in protecting workforces and others from the worst effects of COVID-19.

Federal executive orders or emergency regulations require people to be vaccinated if they are employed by the federal government (including members of the armed services), federal contractors and subcontractors, health care providers and suppliers in the Medicare and Medicaid programs, and employers of 100 or more workers. These requirements are subject to medical and religious exceptions; some mandates allow alternatives to vaccines, like testing. Dozens of lawsuits in multiple courts have been filed challenging the mandates. The employer mandate has already been blocked temporarily, as has the federal contractor mandate.

Medicare and Medicaid Facility Mandate

Perhaps most concerning is the fate of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) vaccine mandate, which applies to 15 types of providers and suppliers that participate in Medicare and Medicaid. These include hospitals, nursing homes, home health providers, hospices, rural health clinics, and community health centers. CMS orders facilities to “require vaccination for all staff that interact with other staff, patients, residents, clients . . . in any location.” “Staff” includes employees, as well as students, residents, volunteers, and contractors. There is no testing alternative to vaccines for health workers because of the grave risks posed to a vulnerable patient population.

Nursing homes (where a third of COVID-19 deaths occurred in the pandemic’s first year) have been a special focus of concern, but other vulnerabilities exist: maternity wards, newborn intensive care units, or health center waiting rooms filled with older patients with diabetes or heart failure. Despite vaccinations’ role in reducing the risk of transmission, severe illness, and death, 22 state attorneys general filed federal cases in Missouri, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas, challenging the mandate. A Florida judge refused to block the mandate — a decision left in place by an appellate court panel (of Democratic-appointed judges). But a Missouri court has preliminarily blocked the mandate in 10 states and a Louisiana court blocked the mandate in the rest of the country.

Both the Missouri and Louisiana courts rely on assertions that CMS failed to follow federal administrative procedures. They question whether CMS had “good cause” for promulgating rules without giving interested parties notice and an opportunity to comment. They also question whether the rule is “arbitrary and capricious.” The questions raised include: Why was the rule needed now, and not months ago? Why has CMS changed its course from relying on persuasion and education to imposing a mandate? While a nursing home mandate may be warranted, must the mandate extend to other health care facilities? These are questions to which CMS responded in the rulemaking record, but the courts mostly rejected this evidence, relying instead largely on its own reasoning.

In reaching these decisions, the courts entertained questionable assertions, like the idea that natural immunity from surviving an infection may be as efficacious as a vaccine in preventing infection or that vaccines are not effective in preventing disease transmission. The courts relied heavily on affidavits from people who claim they will quit if they must be vaccinated or facilities that say they will have to close if the mandate is enforced. However, in facilities that have required vaccinations, few workers have quit. The courts largely ignored or discounted the extensive fact-finding in the 56,000 words of the CMS regulatory preface, which is supported by a brief filed by physician organizations. The courts gave virtually no weight to evidence that vaccines save lives and prevent hospitalizations.

The courts also questioned the legal authority of CMS to adopt the rule. CMS has general statutory authority to adopt rules “necessary to the efficient administration” of Medicare and Medicaid, and for most facilities, it has a responsibility to protect the “health and safety” of patients and residents. CMS imposed the vaccine mandate on many facilities by adding to infection-control standards it has enforced for decades, in most instances without more specific statutory authorization. But the courts held that Congress had not specifically authorized a vaccine mandate. Because the rule affects 10.3 million employees (although most are already vaccinated) and will cost $1.38 billion to implement (a tiny fraction of Medicare and Medicaid expenditures), the courts held that it was of “vast economic and political significance” and needed specific congressional authorization.

Indeed, the courts said that the lack of clear delegation of authority to CMS raises questions as to whether CMS has exercised legislative authority that the Constitution reserves for Congress itself. They also asserted that the Constitution leaves the power to regulate public health, in this case including vaccination requirements, to the states, not the federal government, and suggested that CMS may be unconstitutionally dictating “private medical decisions.”

Will Science or Politics Prevail?

CMS has appealed both the Missouri and Louisiana orders and asked the appellate courts to allow the mandate to go into effect. It seems likely that the Supreme Court will determine whether the mandate survives.

Vaccine mandates have become intensely political. The ability of CMS to protect Medicare and Medicaid patients from a serious, often fatal, disease and the efficacy of vaccines for protecting patients and staff in health care facilities should not be controversial. It is a sad commentary on the American judiciary that federal courts have blocked the implementation of vaccine mandates nationwide for what often appear to be political rather than scientific or legal understandings of the issues involved.