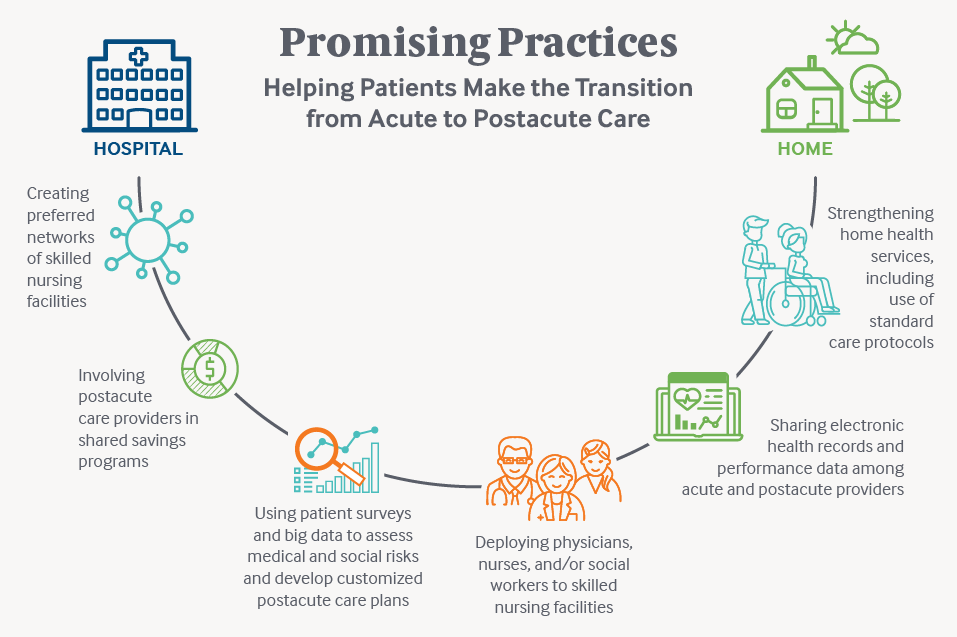

While many U.S. hospitals have concentrated on improving care transitions from hospital to home, far fewer have focused on the transition from hospitals to postacute care settings, including skilled nursing facilities. Increased awareness of variations in spending on postacute care and avoidable complications after hospital discharge — together with value-based payment arrangements — have prompted some physician groups, health systems, health plans, and postacute care providers to collaborate. Among their methods: assessing patients’ risk and identifying the most appropriate setting for them to recover and offering education to help patients regain their functionality and stay well. Better data about what works best for different patients and more aligned financial incentives among acute and postacute care providers could further these efforts.

By Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein

The Institute of Medicine’s 2013 study of Medicare spending upended a common assumption about the biggest drivers of regional variation: it was not hospital use that accounted for the largest the differences in spending across regions, but what happened after patients emerged from hospitals and began making use of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and home health care. The report also traced the dramatic rise in spending on SNF use and other types of postacute care, which more than doubled from 2001 to 2011, making it the fastest-growing sector of health care.1

The rise in the use of postacute care can be traced to Medicare’s decision in the 1980s to stop paying hospitals on a fee-for-service basis and instead make payments based on patients’ diagnoses, not how long they stay. This, together with the increased prevalence of capitated payments under managed care in the 1990s, led hospitals to reduce lengths of stay. Both factors fueled demand for postacute care providers — which include skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), home health agencies, inpatient and outpatient rehab facilities, and long-term hospitals — to help patients recover after surgery or acute illness and return home.2 Demand for postacute care also increased as a function of the aging of the U.S. population and the increasing prevalence of chronic and disabling conditions, which complicate recovery.3 About two of five Medicare beneficiaries end up needing some form of postacute care after a hospitalization.4

In recent years, the introduction of penalties for hospital readmissions as well as the creation of Medicare’s bundled payment program and other accountable care arrangements have encouraged providers to pay more attention to what happens across the full continuum of care.6 To date, the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement program — which encourages providers to integrate care across settings by creating single payments for episodes such as a total joint replacement or treatment for complications of heart failure — has reduced Medicare costs by 4.5 percent (for episodes including the hospitalization and postacute services up to 90 days after discharge) and 7.1 percent (for episodes involving 90 days of postacute care). An evaluation concluded that most savings were achieved by sending more patients home instead of to SNFs and inpatient rehab facilities, and by reducing lengths of stay in SNFs.7

Providers have begun to realize the importance of postacute care. If you have a stroke, so much of how you are going to do will depend on the care you receive after the inpatient setting. Even hip and knee replacements — so much of restoration of function depends on your experience in postacute care.

With the rise of postacute care, there have also been avoidable complications after discharge and unplanned readmissions to the hospital. About one of three Medicare beneficiaries experiences some kind of harmful event in an inpatient rehab facility or SNF (e.g., medication errors or preventable infections), and one of five postacute patients winds up back at hospital within 30 days.8 “We have to do better for patients,” says Raedean VanDenover, who directs accountable care contracting and care coordination at UnityPoint Health’s Des Moines hospital. “It is defeating for patients to feel like they’re in this vicious cycle of being admitted to the hospital then to a SNF, then back to the hospital and back to the SNF. People feel like they are never going to make it back home.”

This issue of Transforming Care looks at efforts led by physician groups, health systems, health plans, and postacute care providers to assist patients in their recovery, improve care, and achieve savings. Their methods include using data to assess patients’ risk and identify the most appropriate setting for them to recover, increasing collaboration among hospitals and postacute care providers, and offering education to patients to help them regain their functionality and stay well.

Promising Approaches

Brooks Rehabilitation

Brooks Rehabilitation in Jacksonville, Florida, offers a continuum of postacute care resources to help its patients, many recovering from strokes, brain or spinal cord injuries, or organ transplants, across their trajectory of recovery. In addition to its 160-bed rehab hospital, Brooks owns skilled nursing facilities devoted to rehab (i.e., with few long-term residents) as well as outpatient therapy and home health care agencies. It was an early participant in the Bundled Payment for Care Improvement program; since 2013, it has delivered some 5,000 postacute episodes of care for hip/knee replacements or revisions, hip/pelvic fractures, heart failure, or spinal surgery.

Over these five years, Brooks clinicians adopted several strategies to orchestrate patients’ recovery, including use of a decision support tool to help them identify the most appropriate setting for each patient. Care navigators offer patients education to help them achieve their goals and support during transitions, and may visit them once they return home. They also use the Patient Activation Measure and other patient surveys to identify those who may need extra help, perhaps because they lack social supports or motivation. “Patients who are more engaged in their recovery are less likely to be readmitted,” says Doug Baer, Brooks’ CEO.9

Physicians provide daily clinical oversight at each of the postacute care settings and use a care management system called “Care Compass” to monitor patients’ functional status, vital signs, risks, and predicted use and length of stay in different care settings. In addition to sharing written summaries, clinicians make “virtual handoffs” via a videoconferencing system to introduce patients to their clinicians in the next care setting and help alert them to any special needs so they can prepare for patients’ arrival.

Such approaches led to improved patient outcomes. Hospital readmissions fell across all diagnoses, but particularly among heart failure patients (rates fell from 34.5 percent from 2009–12 to 17.8 percent in 2017). Brooks also tracked patients’ recovery across care settings, a task complicated by the fact that each postacute care facility must report different types of quality measures to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).10 To streamline measurement, Brooks asked patients to name three types of functional activities they’d like to work on (e.g., grocery shopping, getting in and out of the tub, meal preparation, or driving), and then used the Patient-Specific Function Scale to measure progress toward achieving them on a scale of 1 to 10. The results show that on average Brooks’ patients surpassed the threshold level (a score of 2.7 or more) for achieving a large change in functional improvement over the past four years.

As of June 2017, Brooks had saved Medicare $19 million (a 26 percent reduction) and shared in $12 million in savings after expenses.11 Baer attributes the savings to a combination of strategies, chief among them finding the most appropriate first setting of care and coordinating care to improve outcomes and reduce readmissions.

Suburban Health Organization

Suburban Health is what’s known as a “strategic regional health care organization,” similar to a management services organization. It provides contracting services and promotes shared learning among a group of 10 rural hospitals (including two critical access hospitals) in the Indianapolis area that have joined forces to create four accountable care organizations with Medicare and commercial payers.

While there are hundreds of SNFs in the region, each hospital in the coalition chooses four or five to be in a preferred network — a growing trend among hospitals and their postacute care providers. Until recently, most hospital discharge planners believed that patient-choice regulations prevented them from offering any guidance to patients about which postacute care facility they may want to choose, and most typically offered only a list. But guidance from CMS published last year clarified that “choice” can include information about the quality of different facilities — and in fact as a condition of participation hospitals are obliged to use quality information available about different facilities (e.g., Nursing Home Compare’s Star Ratings system). (To learn more about the potential benefits and risks of preferred SNF networks, see Q&A with Vince Mor, Ph.D., and Rob Mechanic, M.B.A., whose qualitative research includes studies of postacute care quality and efficiency.)12

Suburban hospitals’ approach in selecting preferred facilities was to build on existing relationships and then let partners know their expectations in terms of sharing performance data (including measures of hospital readmissions, length of stay, and emergency department utilization) and ensuring good communication.13 Many of the hospitals hired coordinators, either nurses or social workers, to visit patients at network SNFs to ensure a safe transition of care and make sure they had the ACO’s preferred home health care and other resources ready for their return home.

Improving communication between hospital and SNF clinicians has been a priority. Suburban encourages hospital staff to reach out to SNFs to answer questions about nutritional and medication recommendations, for example, and make sure staff there receive wound care orders or hard copies of prescriptions for narcotics, the lack of which can delay treatment.

Suburban also has encouraged clinicians at the preferred SNFs to dictate a discharge summary for patients’ ambulatory care providers, not a standard practice in the industry. “Patients today are often sicker and more complicated,” says Craig Wilson, M.D., Suburban’s chief medical officer. “That heightened communication provider to provider, during what is pretty important transition in care, deserves more attention.”

The coalition hospitals have seen a 25 percent decline in SNF use and similar decline in SNF length of stay over the past two years. Of all Suburban’s strategies, Wilson believes transparent data sharing between hospitals and SNFs has had the greatest impact. Hospitals have used a portion of the shared savings they’ve earned from ACO contracts to fund an incentive program for physicians that rewards their efforts to achieve population health goals.

The Suburban coalition is pursuing additional approaches to avoid SNF use for less complicated patients, in part by improving home health care through the introduction of standardized disease pathways, starting with congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Atrius Health

Atrius Health, a multispecialty practice with 600 employed physicians in Eastern Massachusetts, has focused on postacute care for the past decade as it has taken on increasing financial risk under commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid contracts.

In 2012, Atrius established a preferred network of SNFs using several criteria: performance measures (including average length of stay, hospital readmissions, number of falls and urinary tract infections, medication reconciliation practices, and others); willingness to collaborate on performance measurement and improvement efforts; and the quality of documentation at discharge. The resulting network — which is designed to encourage tighter links between the hospitals Atrius physicians refer patients to and its preferred SNFs — has 16 SNFs in its top tier and 20 in the next. At top-tier facilities, Atrius physicians or nurse practitioners visit to check on patients. “Having your own clinicians at the SNFs who are aligned with your goals and documenting in your own EMR —you can’t beat that,” says Eliza Shulman, D.O., Atrius’ senior chief innovation engineer. “It consistently delivers higher patient satisfaction and better outcomes, and lower total medical expense.” In facilities where Atrius clinicians do not visit patients, nurse care managers provide attending physicians with information about patient’s prior test results and baseline health status.

Over the past five years Atrius patients have had on average a two-day reduction in length of stay in SNFs and a 2 percent drop in the hospital readmission rate. SNFs are eager to participate in Atrius’ network, Shulman says, because they are likely to make up in patient volume what they may lose through shorter lengths of stay.14

Like Suburban and other providers, Atrius has begun focusing on ways to avoid SNF and hospital stays altogether, which accords with many patients’ preferences. Eighty percent of its total joint replacement patients go directly home after surgery, compared with about 40 percent nationally in 2014, and it’s piloting a program where it will help patients diagnosed with conditions like pneumonia by offering them all needed medical care as well as services like meal delivery at home.15

UnityPoint Health

In 2015, UnityPoint Health’s Raedean VanDenover turned to math teachers, who spent a summer at the Des Moines hospital to gain insight into “real-world” uses for math, to help her figure out which of the region’s 54 SNFs were the best performers. “The second day of crunching the data they came back and said ‘Do you to need to know which ones have a swimming pool or tennis court?’” she recalled. “I said, ‘No, these patients are pretty sick.’” The teachers came up with an index of SNFs, giving the highest rankings to those with the lowest readmission rates, shortest lengths of stay, and lowest total costs per stay.

UnityPoint Health, which derives 20 percent of its revenue from accountable care contracts, used this index and other criteria to create a preferred network of 16 facilities. Social workers, directors of nursing, and other staff from preferred SNFs come together with hospital staff each month to discuss shared problems and brainstorm solutions. A discussion of managing heart failure through diet, for example, encountered resistance from SNF staff who wanted to preserve patient choice. But over time all agreed to offer less salty foods, and to educate patients about why. “They are making the connection that what we do together changes outcomes for both of us but more importantly for patients,” VanDenover says.

The current average length of stay for patients cared for at the preferred SNFs is 19 days, down from 23.6 days in 2015. The readmission rate has edged up slightly (from 12.2% in 2015 to 14.3% in 2017). VanDenover believes the uptick reflects an increase in the medical complexity of patients being discharged to SNFs, as more patients with hip and knee replacements are discharged home.

Deb Jamison, R.N., Pivotal Health Care’s director of clinical services (which operates three preferred-network SNFs in the region) says closer collaboration with UnityPoint Health has meant they now get better documentation of patients’ needs on transfer, particularly because the hospital gave them read-only, HIPAA-compliant access to patients’ electronic medical records.

This year, Pivotal and most of the other preferred SNFs entered into an accountable care arrangement with UnityPoint Health under which the SNFs earn shared savings, based on achieving benchmark performance on measures of both quality and utilization.16 Participating facilities also must use some type of electronic health record system and have a registered nurse on site for 16 hours a day (most SNF nurses are licensed practical nurses) so that SNFs can serve more clinically complex patients. Pivotal joined UnityPoint Health’s ACO prior to this latter requirement. It hopes to achieve this standard, but has struggled due to a shortage of nurses in the area, Jamison says.

Using Big Data to Inform Decision Making: naviHealth’s Approach

Brentwood, Tennessee–based naviHealth was founded in 2012 to manage care transitions on behalf of health systems and plans interested in improving postacute care. Clients tend to start by trying to develop standard approaches for care following joint replacement procedures, for which there is tremendous variation in postacute use.17 At one hospital, for example, one surgeon sent 70 percent of his patients to an inpatient rehab facility, while another sent most patients directly home, with similar outcomes and a sixfold difference in price, says Carter Paine, naviHealth’s chief operating officer.

To help clients figure out what types of postacute care may be needed for different patients, naviHealth uses risk-assessment and decision support software. Patients are assessed before surgery or at the time of hospital admission, then regularly after, taking into account their diagnoses and comorbidities, as well as their cognitive and ambulatory impairments, ability to complete activities of daily living, and living situation. The software then combs through its database on the health experiences of 3 million patients (de-identified) to find those in similar situations and identify which rehabilitation regimen worked best for them.

Paine says that most of naviHealth’s clients involved in the bundled payment program have been able to save an average of 8 percent on postacute care, mostly from reducing length of stay in SNFs or directing patients to the most appropriate care setting. Their Medicare Advantage clients, which wield more direct control over usage than do providers, tend to save more than 15 percent on postacute spending.

MVP Health Care, a nonprofit health plan serving Medicare Advantage members and others in New York and Vermont, is leveraging naviHealth’s analytic capabilities to identify opportunities for improvement, such as cases when hospitals may too precipitously discharge patients, or cases when patients would be better off with home health care than going to a SNF.

Policy Implications

The experiences of hospitals and postacute providers indicate there is ample opportunity for closer collaborations to improve postacute care outcomes. To build on the progress made, experts say, we’ll need better ways to assess the quality and efficiency of postacute care, as well as more closely aligned reimbursement approaches.

Standardized Assessment Needed

There have been qualitative studies of how hospitals are collaborating with postacute care providers, but not rigorous evaluations. “We need to compare data from all of us who are testing models,” says Brooks Rehab’s Baer. “What are the best practices? Who is achieving what and how are they doing it? Lack of that type of feedback in the bundled payment program has been disappointing.” (Many postacute care providers are also disappointed that the next iteration of the bundled payment program, launching in October, does not include a track just for postacute care episodes, as the program had previously done.18)

In particular, better evidence is needed about ways to manage care for the rising number of patients with multiple chronic conditions. Improving transitions for those with common surgeries like joint replacements is low-hanging fruit, naviHealth’s Paine says, since changing surgeons’ rehab recommendations is relatively easy when compared with orchestrating pathways for medically complex patients. But meaningful change will only happen when health systems focus on improving postacute care for a range of conditions. “If you do just one procedure or condition, you are not really affecting the discharge planner functions,” he says. “But as you take on more everyone is on the same page in terms of incentives, data, and learning. This includes case management staff in the hospital. They have to buy in or it’s not going to work.”

The Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014 may help generate evidence about what processes promote patients’ smooth and sustained recovery.19 It created standardized measures across postacute care settings that focus on improvements or deteriorations in patients’ physical and cognitive function, skin integrity, incidence of falls, transfer of health information, resource use, and readmission rates. Starting this year, providers will receive confidential reports on their performance, and next year the data will be made public.20

Aligning Financial Incentives

Another hurdle to coordinating postacute care is that each setting has different accreditation and staffing requirements — and different Medicare payment and regulations. “You can see the complexity and cost built into this system,” says Richard Kathrins, Ph.D., chair of the American Medical Rehabilitation Provider Association (AMRPA), which represents more than 600 rehab hospitals in the U.S. “We could eliminate those siloes and move the patient seamlessly between and among levels of care the way the patient moves in the acute-care hospitals if we didn’t have to have separate and disparate requirements.”

A proposal to pilot a single prospective payment across postacute providers was put forth by the AMRPA and included in the Affordable Care Act, but it did not move forward. But experts say the IMPACT Act’s creation of standardized measures lays the groundwork for eventual creation of a unified payment system.21 “That direction is where things are headed — it will reduce variation enormously,” says Carol Raphael, a senior advisor at Manatt Health Solutions.

In particular, holding SNFs financially accountable for outcomes may encourage them to invest in higher-skilled workforce and other tools, including telehealth, that could improve care and avoid return trips to the hospital. The incentives must be carefully designed to ensure providers don’t avoid patients with complex needs, including those with dementia and other comorbid conditions.

In the meantime, the bundled payment program demonstrates the potential of aligning incentives across providers — discouraging overuse and offering greater flexibility to deploy resources to accommodate patients’ goals and needs. “An aide may be more effective than a home health agency, for example,” says MVP Health Care’s chief medical officer, Elizabeth Malko, M.D. “I’ve deployed community health workers to help coordinate the medical and social needs of high-risk patients during their recovery.”

Ultimately, the experts say, most of the savings will come from sending more patients directly home from the hospital, and giving their health plans and providers the flexibility to provide appropriate services there. “This is one of the times where what people want is aligned with payers’ interest,” Raphael says.

Notes

1 The Institute of Medicine found that postacute care accounted for 73 percent of the geographic variation in Medicare spending per beneficiary, despite accounting for only 20 percent of total Medicare spending. Institute of Medicine, Variation in Health Care Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography, National Academies Press, 2013. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/18393/variation-in-health-care-spending-target-decision-making-not-geography. Also see MedPac (2013 June), A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program. Available at http://67.59.137.244/documents/Jun13DataBookEntireReport.pdf.

2 See for example R. Burke, E. A. Whitfield, D. Hittle et al., “Hospital Readmission from Post-Acute Care Facilities: Risk Factors, Timing, and Outcomes,” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, March 1, 2016 17(3):249–55. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4847128/

3 C. Raphael, S. Anthony, and A. Fiori, “Reinventing Long-Term Care and Post-Acute Care: Integrating into a New Healthcare System,” Presentation (Manatt Health Solutions, n.d.).

4 In 2015, about 43 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in the fee-for-service program were discharged to postacute care providers, according to MedPAC. See Medicare Patient Advisory Committee, A Data Book: Health Care Spending and the Medicare Program (MedPAC, June 2017).

5 L. M. Keohane, S. Freed, D. Stevenson et al., Postacute Care Spending Trends During the Medicare Spending Slowdown (The Commonwealth Fund, forthcoming).

6 A study of a cohort of accountable care organizations engaged in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) found participation in the MSSP was associated with significant reductions in postacute care spending without deterioration in readmission or mortality rates. See J. M. McWilliams, L. G. Gilstrap, D. G. Stevenson et al., “Changes in Postacute Care in the Medicare Shared Savings Program,” JAMA Internal Medicine, April 1, 2017 177(4):518–26.

7 L. Dummit, G. Marrufo, J. Marshall et al., CMS Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative Models 2-4: Year 3 Evaluation and Monitoring Annual Report (Lewin Group, Oct. 2017).

8 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Inspector General, Adverse Events in Skilled Nursing Facilities: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries (DHHS OIG, Feb. 2014). See also A. N. Fleischman, M. S. Austin, J. J. Purtill et al., “Patients Living Alone Can Be Safely Discharged Directly Home After Total Joint Arthroplasty: A Prospective Cohort Study,” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, Jan. 2018 100(2):99–106; and R. E. Burke, E. A. Whitfield, D. Hittle et al., “Hospital Readmission from Post-Acute Care Facilities: Risk Factors, Timing, and Outcomes,” Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine, March 1, 2016 17(3):249–55.

9 A 2014 study of adults discharged from a safety-net hospital found those with lower levels of patient activation had a higher rate of readmissions within 30 days. S. E. Mitchell, P. M. Gardiner, E. Sadikova et al., “Patient Activation and 30-Day Post-Discharge Hospital Utilization,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Feb. 2014 29(2):349–55.

10 For example, inpatient rehab facilities must use the IRF-Patient Assessment Instrument, SNFs must use the Minimum Data Set, and home health providers use the Outcome and Assessment Information Set.

11 Savings based on reductions from historical spending for similar types of patients. Brooks’ $12 million in shared savings was based on 20 percent savings, which is the cap that Medicare places on shared savings.

12 D. A. Tyler, E. A. Gadbois, J. P. McHugh et al., “Patients Are Not Given Quality-of-Care Data About Skilled Nursing Facilities When Discharged from Hospitals,” Health Affairs, Aug. 2017 36(8):1385–91; and E. A. Gadbois, D. A. Tyler, and V. Mor, “Selecting a Skilled Nursing Facility for Postacute Care: Individual and Family Perspectives,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Nov. 2017 65(11):2459–65.

13 Suburban also monitors resource utilization group (RUG) rates, which are used by SNFs to estimate the intensity of services a patient will require. Its goal is to ensure efficiency gains achieved by shortened lengths of stay are not accompanied by higher risk ratings, which would increase payment and offset these gains.

14 The traditional Medicare program pays SNFs per day by type of treatment provided, with higher payments for more intensive rehabilitation services. Generally, rehab patients are much more lucrative to SNFs than are long-stay residents, whose long-term care is often paid for by Medicaid.

15 For more on Atrius’ hospital at home program, which is a partnership with Medically Home, see https://www.atriushealth.org/news-media/2017-releases/medically-home-group-launches-the-future-of-medical-care. For information on the percent of patients visiting institutional postacute settings after total joint replacement surgery, see T. D. Tarity and M. M. Swall, “Current Trends in Discharge Disposition and Post-Discharge Care After Total Joint Arthroscopy,” Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, Sept. 2017 10(3)397–403.

16 UnityPoint also retains 3 percent of the facilities’ Medicare billings as a quality withhold. The facilities earn back those funds based on performance on a variety of process and utilization metrics (e.g., rates of influenza vaccination, average length of stay, and unplanned 30-day readmissions).

17 See, for example, Institute of Medicine, Variation in Health Care Spending: Target Decision Making, Not Geography, Report brief (National Academies Press, July 2013).

18 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, BPCI Advanced (CMS, n.d.).

19 See Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, IMPACT Act of 2014 Data Standardization & Cross Setting Measures (CMS, n.d.).

20 American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living, Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act of 2014 (AHCA & NCAL, n.d.).

21 For more on the Continuing Care Hospital pilot, see American Medical Rehabilitation Providers Association, The Continuing Care Hospital Pilot: Recommendations for Implementation (AMRPA, Aug. 2011).