TRANSFORMING CARE

How Health Care Organizations Are Preparing for Climate Shocks and Protecting Vulnerable Patients

Cars submerged in Orlando, Florida, following Hurricane Ian on October 1, 2022. As climate change contributes to stronger weather events in Florida and across the U.S., health care organizations are taking steps to become more resilient. Photo: Bryan R. Smith/AFP via Getty Images

Cars submerged in Orlando, Florida, following Hurricane Ian on October 1, 2022. As climate change contributes to stronger weather events in Florida and across the U.S., health care organizations are taking steps to become more resilient. Photo: Bryan R. Smith/AFP via Getty Images

-

Health care organizations on the front lines of extreme weather events are working to become more climate resilient and protect vulnerable patients.

-

Hospitals and clinics are assessing the potential impacts of climate change in their communities, shoring up their infrastructures, and putting plans in place to help patients most at risk.

-

Health care organizations on the front lines of extreme weather events are working to become more climate resilient and protect vulnerable patients.

-

Hospitals and clinics are assessing the potential impacts of climate change in their communities, shoring up their infrastructures, and putting plans in place to help patients most at risk.

As Hurricane Ian barreled toward Florida last month, the state’s federally qualified health centers prepared by testing satellite phones so they could keep in touch with emergency officials during the storm and by readying to deploy generators, tents, and wash stations to help people after it passed. Experience shows that people aren’t vulnerable just to flooding and strong winds during hurricanes but also to the longer-term disruptions they bring. A multidecade study found a 33 percent higher death rate after major hurricanes in the United States due to injuries, infectious and parasitic diseases, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and fallout from neuropsychiatric conditions like anxiety and depression.

As a changing climate contributes to stronger hurricanes, wildfires, heat waves, and other extreme events, hospitals and clinics are increasingly finding themselves on the front lines. Not only must they shore up their infrastructures to withstand climate shocks, they also must help patients whose health and safety are affected. In this issue of Transforming Care, we profile health care organizations that are taking steps to become more climate resilient and protect vulnerable patients, including those who are elderly, have chronic conditions, or lack social supports.

Shoring Up the Safety Net

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and free clinics, which care for more than 30 million low-income Americans, are an obvious place to start when developing systems to support patients most at risk during climate disasters. Yet, not all institutions have resources and knowhow to prepare for climate change, and much of the money devoted to resiliency in health care has gone to hospitals as part of emergency preparedness funding. To rebalance the scales, the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, together with Americares — a nonprofit that provides medicines, supplies, and training to health centers around the country — are creating a toolkit to help safety-net clinics prepare for climate shocks and protect patients from harm. “These clinics have gotten the least amount of attention and the least amount of investment in preparedness but see the patients who are most vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis,” says Kristin Stevens, M.S., Americares’ director of climate and disaster resilience.

The Climate Resilience for Frontline Clinics Toolkit is funded by the biotechnology firm Biogen and is being developed in consultation with staff from nine clinics in four states that experienced major climate events: heat waves, floods, hurricanes, and wildfires. It also draws on findings from a survey of some 450 clinicians and administrators at safety-net clinics in 47 states about their climate change experiences. In addition to educating clinicians and patients about the health effects of climate events, the toolkit offers operational guidance for providers and health system administrators to ensure they can maintain access to care during and after these events.

Staff from the San José Clinic, which operates two charitable clinics for uninsured patients in and around Houston, Texas, shared their experiences responding to heat waves and hurricanes. Run largely by volunteer clinicians, the clinic serves roughly 4,000 patients each year. Chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension are so common that the average patient receives 10 to 12 different medications per year.

When Hurricane Harvey struck in the summer of 2017, the clinic had enough warning to give patients extended supplies of medication, including insulin stored in coolers in case power went out. “We knew if they had to go to Walgreens or CVS or anywhere else, there was no way they’d be able to afford the medications,” says Adlia Ebeid, Pharm.D., chief clinical officer.

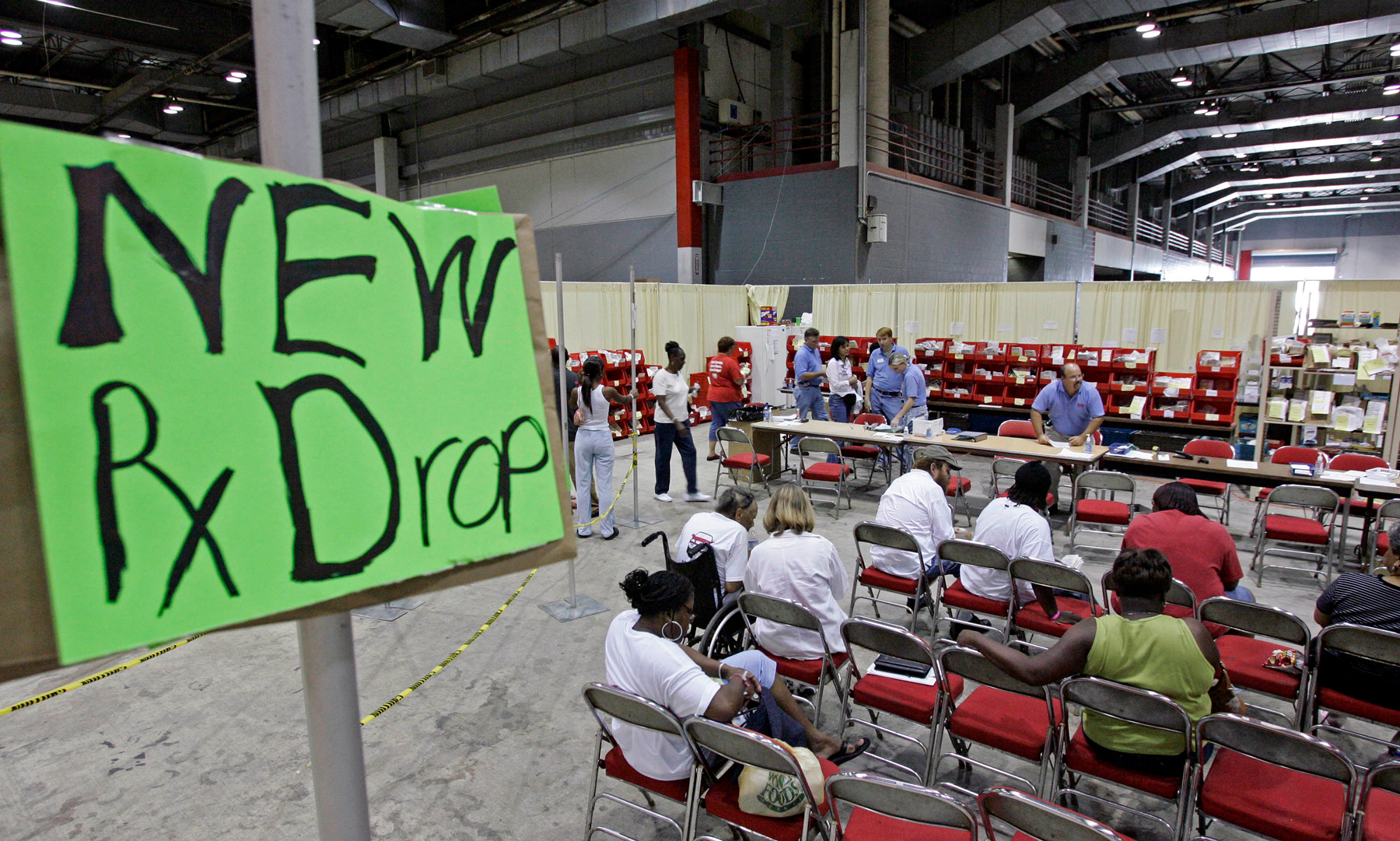

What the clinic was not prepared for were the supply chain disruptions that followed when FEMA required FedEx and other carriers to pause deliveries to all but authorized recipients. “The CEO of Dispensary of Hope, a charity that donates medicine, ended up driving to Houston in the middle of the night to deliver a truck full of supplies,” Ebeid says. Once restocked, clinic staff helped to fill treatment gaps by serving people who weren’t regular patients — supplying psychiatric medications to people sheltering in the convention center and filling prescriptions for those who had insurance but whose pharmacies had flooded.

The excessive heat of recent years presents a different set of challenges. “We have patients whose only means of air conditioning is their car,” Ebeid says. Many work outdoors in construction or landscaping and are reluctant to take breaks to eat or hydrate. If given the choice between taking an antibiotic that makes them sensitive to sunlight and working, many will forgo the medication, she says. “We are learning to ask more important questions about their living conditions because even at room temperature, some medications can end up being compromised,” she says. Clinic staff encouraged the toolkit developers to create a standardized set of questions that could be embedded into electronic medical record systems to assess such risks.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, clinic staff realized that families who may have been undocumented weren’t seeking help for fear of being deported. To help them, staff began going door to door to visit patients, wearing white coats to engender trust. “We found people standing in knee-high water in their houses,” Ebeid says. Clinicians offered tetanus shots and asthma inhalers to people in homes where mold was becoming problematic and ultimately established a second free clinic in Rosenberg, Texas, a town on the outskirts of Houston where outreach workers saw the greatest need.

Staff from the Community Care Clinic of Dare, a free clinic in Nags Head on the Outer Banks islands off North Carolina, also contributed to the toolkit by sharing their experiences helping uninsured patients cope with heat, many of whom worked in maintenance or other jobs related to tourism. Alex Hodges, D.N.P., F.N.P.-C., one of the clinic’s nurse practitioners, gives patients toolkit materials to explain how their medication regimens for diabetes and hypertension may be affecting them on extremely hot days.

“One of the largest things I’ve seen this summer is dehydration,” says Hodges. “I’ve had to adjust patients’ blood pressure medications because diuretics make them urinate more and they’re already dehydrated because they're sweating, working outside.”

Some patients’ situations are more perilous because they’re unable to cool down at night; some are homeless or crowded into substandard housing with other families. “One patient came to see me whose landlord controlled the AC and he had it set at 80,” she says. “Then the power got turned off, then the water got turned off. The patient continued to take his insulin, continued to take his blood pressure medicine. But he wasn't hydrating. And he continued to do some yard work to earn some money so that he could go to the grocery store. He ended up going to the hospital to have IV fluids.”

Learning From Hurricanes Katrina and Ida

CrescentCare, an FQHC in New Orleans that treats 13,500 patients annually, developed new practices for managing climate disasters after two hurricanes — Katrina and Ida — severely disrupted operations and displaced staff and patients to neighboring states. Noel Twilbeck, Crescent Care’s CEO, spent the immediate aftermath of Katrina in Houston, where he sheltered in an aunt’s house along with 26 other people, six dogs, and an iguana. A skeleton crew of staff, working from different cities, sought ways to get medication to patients who were covered by Louisiana’s AIDS Drug Assistance Program but had relocated to Mississippi or Texas. Emergency grants from pharmaceutical companies enabled the clinic to keep its doors open while it wasn’t earning money from providing services. In 2013, the clinic became an FQHC, putting it on stronger financial footing.

In 2021, Hurricane Ida left some residents of New Orleans without power and fresh food for weeks. Well in advance of that storm, CrescentCare staff began strategizing ways to ensure that vulnerable patients could maintain contact with their providers during disruptions. They distributed donated smartphones and remote monitoring tools to more than 500 patients. This year, the FQHC also received grant funding from Direct Relief — a California-based humanitarian aid organization — to establish itself as a “community lighthouse,” a safe place where residents can charge phones and cool off. The city aims to have as many as 100 such hubs in churches and other faith-based organizations; CrescentCare’s will be the first located in a commercial site. Leaders plan to use the space to provide basic health services, store medications in climate-controlled conditions, and partner with community-based organizations that can provide services like harm reduction programs or food distribution during emergencies.

“Nobody really knows how to respond in a disaster like the people who live there,” says Joe Hui, the FQHC’s director of communications. “Having this power to protect ourselves and care for ourselves and our neighbors is a big shift from past disasters,” he says. The FQHC also hopes to establish health teams at local churches that can canvass neighborhoods and identify people at particular risk during power outages, such as those dependent on medical devices.

While New Orleans’ network of “community lighthouses” are still in development, there are some 160 “community resilience” hubs in operation or development across the U.S. Rather than serving strictly as emergency shelters where people can sit out storms and power outages, the hubs aim to strengthen neighborhoods by offering job training, child care, recreational activities, and other resources. Kristin Baja, M.A., M.S., director of direct support and innovation at the Urban Sustainability Directors Network, helped establish the first community resilience hubs in the U.S. — in Baltimore in 2014 — after hearing from residents that they wouldn’t trust nor use a government-run shelter. Her organization fosters the development of hubs by promoting partnerships between community-based organizations and local governments. “There’s a huge opportunity for us to bring health and health care into [sites] that are community designed and community trusted,” she says.

Staff at the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) — created in January 2021 by President Biden and tasked with protecting people from the health effects of climate change, particularly those most at risk — have taken a keen interest in this model. They’re exploring whether resilience hubs could fill day-to-day needs in communities for food banks, legal aid, or clinical care, then scale up services to respond to hurricanes, heat waves, or other events.

Making Climate Part of Risk Assessments

While some safety-net clinics are working on the ground to protect patients in their communities from climate shocks, a few health systems have begun thinking broadly about how climate change will affect patients. One is Providence, a Renton, Washington–based health system with 51 hospitals in seven states that has been cited as a leader in efforts to reduce its climate footprint. (Providence was also the subject of a recent New York Times investigation showing it had systematically and incorrectly billed low-income patients who were entitled to free care; it has since begun reaching out to these patients to offer refunds and notes it has reviewed its collection practices.) Staff at Providence have spent the last 18 months assessing environmental hazards that affect patients in different markets, including poor air quality and proximity to freeways, industrial sites, and sources of toxic waste.

The assessment also tracked regional changes in climate that can affect patients. “In some areas, we are looking at sea level rise and in other parts of the country, fires and wildfire smoke,” says Elizabeth Schenk, Ph.D., R.N., F.A.A.N., Providence’s executive director of environmental stewardship.

To help clinicians respond, health system leaders developed a dashboard in 2021 to identify patients most at risk during extreme weather events, including those with serious mental illnesses, dementia, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma as well as those who depend on oxygen, dialysis, or ventilators to survive. The dashboard is linked with Providence’s care management and care coordination platform and draws data from electronic medical records, allowing care managers and health system administrators to filter results by region, zip code, demographic characteristics, and diagnoses. “By overlaying weather, climate, and air quality data, we can see who stands out at risk,” Schenk says. The health system used the dashboard in the Pacific Northwest to identify which patients were most at risk from heat waves and provided them with information about cooling centers. Providence’s community health investment team has begun to use the information to target upstream investments in things like increasing tree canopies and improving cooling and air filtration in homes, she says.

Foregrounding Health Equity

Impoverished communities — already burdened by environmental pollutants such as poor air quality and lead paint in homes — also face higher risks from climate change. These areas, which are disproportionately communities of color, have experienced decades of disinvestment and harmful social policies including redlining and eviction practices that make it difficult to build wealth, a protective buffer in heat waves and other emergencies.

In Rhode Island, the state has encouraged community-based organizations to partner with health care providers and residents to tackle social and environmental issues that affect health, including climate change. It has established 15 “health equity zones” that enable communities of different sizes to set priorities, using public and private funding to launch new initiatives.

The West Elmwood 02907 Health Equity Zone is named after the zip code encompassing some of the poorest neighborhoods in Providence. About 60 percent of residents are Latino and 18 percent are Black; two-fifths are immigrants to the U.S. The health equity zone’s leaders have partnered with the American Lung Association, Brown University, and Rhode Island’s health department to monitor particulate matter in the air and ozone and mitigate the effects of climate change by reducing heat islands and increasing the tree canopy. The focus on air quality is part of the health equity zone’s broader effort to improve asthma management among the neighborhood’s children, who have significantly higher rates of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations relative to kids living with asthma in wealthier parts of the city.

ONE Neighborhood Builders, a convening agency for another health equity zone, Central Providence Opportunities, joined with the Woonasquatucket River Watershed Council to create a film to help neighborhood residents prepare for floods and other extreme climate events. Surveys had found that many residents were concerned about flooding; many recalled the “100-year flood” in 2010 that destroyed homes and other infrastructure in Providence and across the state. Among other steps, the film advises residents to create emergency plans and sign up for the Code Red app to stay informed during emergencies.

Regional Responses

When it comes to preparing for climate shocks, health care organizations need to work together. Federal funding through the Hospital Preparedness Program, launched after 9/11, supports the creation of regional health care coalitions. There are over 300 such coalitions across the country; most involve hospitals, public health agencies, and emergency service providers but they are increasingly involving long-term care facilities, clinics, home health agencies, and other providers. “Particularly for climate-related issues, it’s really important to have community-based organizations involved,” along with pharmacists, dialysis centers, addiction clinics, and other providers says Eric Toner, M.D., senior scholar with the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

One of the most robust health care coalitions is the Northwest Healthcare Response Network, formed in 2005 as a collaboration between the Seattle & King County Public Health Department and local hospitals. It has since expanded to include most hospitals in western Washington State, as well as medical groups and long-term care facilities. During the pandemic, the coalition helped establish the Washington Medical Coordination Center to balance each hospitals’ load of COVID-19 patients.

The heat dome of 2021 in the Pacific Northwest strained health care providers’ capacity — as large numbers of patients turned up at EDs and hospitals struggled to cool buildings. “Some of our medical equipment — including imaging and radiation systems — isn’t set up to accommodate the degree of heat we received,” says Onora Lien, M.A., the coalition’s executive director. During the less severe heat waves of 2022, hospitals were more prepared with new cooling systems as well as more body bags, which are filled with ice water and used to cool patients experiencing heat stroke. The coalition also worked with public health departments to share information with long-term care facilities on strategies for keeping elderly residents cool.

Collaboration has enabled hospitals to identify shared challenges, including finding ways to discharge patients who are ready to leave their facilities but don’t have safe places to recuperate. “I can’t underscore enough the fundamental risk that poses to overall resiliency and readiness for anything. If we don’t address this, we are failing ourselves and the assumption that we can be resilient to anything,” Lien says.

Lessons

Though the effects of a changing climate are very much upon us, efforts to build more resilient health care organizations are still nascent. Experts in emergency preparedness as well as people with on-the-ground experiences offered the following guidance to health system leaders and policymakers.

Be adaptable.

The type and impact of climate-related events differ by region, and they are likely to evolve in ways that can be hard to predict. Heat may be the only exception. “We know when it’s happening, we know what negative health effects it can have, and we should be able to prevent them,” says John Balbus, M.D., M.P.H., interim director of the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. Preparing for other climate disasters requires a nimbler approach. “We tend to overspecialize in trying to predict what the next emergency is going to be and tailor capacity when what we really need to build are more flexible systems that are able to respond quickly to a variety of challenges,” says James Lawler, M.D., M.P.H., director of international programs and innovation at the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Global Center for Health Security.

Indeed, CrescentCare, the FQHC in New Orleans, found that many of Hurricane Katrina’s lessons weren’t applicable to Hurricane Ida because technology had evolved and the points of failure were very different (e.g., a lack of cell service during Katrina versus a lack of diesel fuel during Ida). In the absence of predictability, collaboration and strong social ties become more important.

Health systems also should develop contingency plans for staff, who may face gut-wrenching choices during a climate emergency as occurred in Boulder, Colorado, last year when a rapidly moving fire took out homes of medical staff. “How do you choose between going to help patients in the clinic or hospital where you work and going to protect your home, where you’ve got family and pets?” asks Aaron Bernstein, M.D., M.P.H., who co-leads Climate MD at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health. During Katrina, a full third of CrescentCare’s staff suffered significant damage to their homes or lost them entirely, and clinic staff spent much of their time trying to meet basic needs for food, gas, and electricity in the aftermath of both Katrina and Ida.

Use funding and policy to promote collaboration among health care organizations and direct resources to safety-net facilities.

One model for promoting collaboration across regions is the disaster resource hospital. Often an academic medical center, the hospital serves as a hub for coordinating public health and health system responses to emergencies. The federal government is funding pilots of the model, which are now underway in Atlanta, Boston, Denver, and Omaha. Updating guidelines for regional coalitions established through the Hospital Preparedness Program to include clearer expectations for collaboration among competing institutions could also help, Toner says. “The CMS preparedness rule, which outlines provider requirements, also needs to be updated, strengthened, and tied to CMS reimbursement,” he says.

Still, some health care institutions have much greater capacity to invest in climate preparedness than others, and targeted efforts may be needed to support safety-net clinics and hospitals. Communities where residents have worse access to health care on a day-to-day basis also bear disproportionate impacts during health emergencies, says Lawler, who leads Omaha’s pilot of the disaster resource hospital.

Integrate plans for climate resiliency into all facets of health care delivery.

Given that it does not have congressionally appropriated funding to launch its own initiatives, the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity is leveraging existing authorities and programs in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to increase support for populations who suffer the most serious health effects of climate change. There are many levers to pull without changing regulation. The low-income home energy assistance program can provide funding to cover air conditioning in addition to covering heating costs; FQHCs can hire community health workers to educate patients about the health risks of heat; and provider visits including annual wellness visits can be used to assess risk. Existing tools, such as community health needs assessments, can be used to identify residents’ climate-related risks and target investments in resiliency. For example, CMS recently granted Oregon a Medicaid waiver to allow coverage of medically necessary air conditioners, heaters, humidifiers, air filtration devices, generators, and refrigeration units when certain requirements are met. “We’re just scratching the surface of what’s possible,” says Arsenio Mataka, J.D., HHS’s senior advisor on Climate Change and Health Equity.

Adverse Events Among Hospitalized Patients Declined Over the Past Decade

A new study takes a high-level look at patient safety in hospitals over the past decade. According to a review of Medicare data from 2010 to 2019, the rate of adverse events — problems such as hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, and drug interactions — decreased significantly among patients admitted for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, pneumonia, and major surgical procedures. After adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, researchers also detected a significant decrease in the rates of adverse events among patients hospitalized for all other conditions. Noel Eldridge et al., “Trends in Adverse Event Rates in Hospitalized Patients, 2010-2019,” Journal of the American Medical Association 328, no. 3 (July 2022):173–83.

Case Management to Address Social Needs Reduce ED and Hospital Use

A large, randomized trial in Contra Costa County, California, tested whether case management to address unmet social needs — including food insecurity and unemployment — could reduce emergency department (ED) and hospital use among Medicaid beneficiaries at high risk of avoidable utilization. After one year, ED use among the intervention group decreased by 4 percent and hospitalizations decreased by 11 percent. While the results are promising, the authors conclude that the savings may not fully cover the program costs and efforts are needed to engage more people in case management services; only 40 percent of the intervention group elected to participate in the case management program. Daniel M. Brown et al., “Effect of Social Needs Case Management on Hospital Use Among Adult Medicaid Beneficiaries,” Annals of Internal Medicine 178, no. 8 (August 2022):1109–17.

Can States Go It Alone to Reform Health Care?

This study assesses the progress states made in implementing health reforms through the State Innovation Model (SIM), which was run by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation between 2013 and 2019. Detailed case studies of SIMs in Arkansas, Connecticut, New York, Oregon, Tennessee, and Washington found that states that made the most progress had prior successful health reforms and sustained stakeholder, bureaucratic, and political support. The author suggests that, beyond funding, states with less health reform experience could benefit from technical assistance and advice from the federal government. Anne-Marie Boxall, “What Does the State Innovation Model Experiment Tell Us About States’ Capacity to Implement Complex Health Reforms?” The Milbank Quarterly 100, no. 2 (June 2022):525–61.

Insurance Status, Language, and Neighborhood Social Vulnerability May Impede Access to COVID Treatment

This study sought to explore whether a patient’s race or ethnicity mediated their access to monoclonal antibody infusions to treat COVID-19. Among a random sample of high-risk adults with COVID-19 who were referred for monoclonal antibody therapy, there was no significant difference in racial composition between patients who declined (n = 25) and accepted (n = 378) treatment. However, only 44.6 percent of Hispanic/Latino patients and 31.0 percent of Black patients received treatment compared to 64.1 percent of white patients. Using spatial and multivariable analyses that adjusted for age, race, insurance status, non-English primary language, county Social Vulnerability Index, illness severity, and total number of comorbidities, the authors found race was not a statistically significant factor in receiving treatment. Instead, they found patients who were uninsured or whose primary language was not English were less likely to receive treatment, as were those living in socially vulnerable communities. En-Ling Wu et al., “Disparities in COVID-19 Monoclonal Antibody Delivery: A Retrospective Cohort Study,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 37, no. 10 (August 2022):2505–13.

Home Visits from Nurses Did Not Improve Birth Outcomes Among Medicaid Beneficiaries

A randomized clinical trial tested whether nurse home visits could improve maternal birth outcomes among Medicaid-eligible pregnant people in South Carolina. Nurses offered education and assessments and helped pregnant people set goals during the visits, which began during the prenatal period (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) and continued for two years postpartum. The study found outcomes for the intervention group were not significantly better for any of the maternal and newborn measures. The incidence of adverse birth outcomes was 26.9 percent in the intervention group and 26.1 percent in the control group. The authors note that assessing the effect of the program on other important measures, including child development and maternal life course, would require longer assessment periods. Margaret A. McConnell et al., “Effect of an Intensive Nurse Home Visiting Program on Adverse Birth Outcomes in a Medicaid-Eligible Population: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of the American Medical Association 328, no. 1 (July 2022):27–37.

Missed Opportunities to Head Off ED Visits, Hospitalizations

Using records from a large midwestern health system, researchers found a significant percentage of patients with ED visits or hospitalizations for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions had received outpatient care in the preceding weeks and months. The study, which analyzed data from 2012 to 2014, found that among patients seen in the ED for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, 11.9 percent, 16.3 percent, and 21.67 percent received outpatient care in the 14, 30, and 60 days prior, respectively. Of those hospitalized for such conditions, 29.1 percent, 39.9 percent, and 53 percent received outpatient care in the 14, 30, and 60 days prior, respectively. The researchers suggest that these findings point to ample opportunities to intervene. Sharmistra Dev et al., “Quantifying Ambulatory Care Use Preceding Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations for Ambulatory Care Sensitive Conditions,” American Journal of Medical Quality 37, no. 4 (July/August 2022):285–89.

Becoming Trustworthy Health Care Organizations: A Conceptual Model

Rather than focusing on whether patients trust their health care providers and the health system, the authors suggest flipping the script to improve the trustworthiness of health care organizations and systems. They suggest developing and publicly reporting measures to enable patients, particularly from historically marginalized groups, to assess the trustworthiness of their providers could promote health equity. Andrew Anderson and Derek M. Griffith, “Measuring the Trustworthiness of Health Care Organizations and Systems,” The Milbank Quarterly 100, no. 2 (June 2022):345–64.

New Approach to Assessing the Quality of Diabetes Care Needed

The authors of this Health Affairs analysis argue that while more and more measures have been created in recent decades to measure the quality of diabetes care, there have not been measurable improvements in care quality or treatment outcomes. To focus on what matters and incentivize improvement, they argue for a new approach: the adoption of new measures across six domains of quality, with top-line measures used for reporting and reimbursement and others used for evaluation. David H. Jiang et al., “Modernizing Diabetes Care Quality Measures” Health Affairs 41, no. 7 (July 2022):955–62.

More Than Half of Mental Health Providers in Oregon Medicaid Managed Care Networks Not Actually Providing Care to Medicaid Beneficiaries

A new study evaluated whether mental health care providers listed in Oregon Medicaid’s managed care organization (MCO) directories are actually providing care to beneficiaries. Overall, 58.2 percent of network directory listings were “phantom” providers who did not see Medicaid patients, including 67.4 percent of mental health prescribers, 59.0 percent of mental health non-prescribers, and 54.0 percent of primary care providers. Jane M. Zhu et al., “Phantom Networks: Discrepancies Between Reported And Realized Mental Health Care Access In Oregon Medicaid,” Health Affairs 41, no. 7 (July 2022):1013–22.

Continuity of Primary Care Offers Great Value, Study Finds

Researchers sought to measure the value of Medicare beneficiaries having continuous care with the same primary care physician and within the same practice. The study found that for every 0.1 increase in physician continuity (using an index ranging from 0 to 1), there was a $151 decrease in spending per beneficiary per year. For every 0.1 increase in practice continuity, there was $282 less spending per beneficiary per year. Both physician- and practice-level continuity were associated with lower probabilities of hospitalization, ED visits, admissions for ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, and hospital readmissions. Zhou Yang et al., “Physician- Versus Practice-level Primary Care Continuity and Association with Outcomes in Medicare Beneficiaries,” Health Services Research 57, no. 4 (August 2022):914–29.

Will REACH ACO Model Promote Health Equity?

A commentary in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests most value-based payment programs led by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have not measurably improved quality nor reduced expenditures, and some programs have even been regressive — transferring resources away from safety-net hospitals and potentially widening inequities in care. By more frequently penalizing institutions with high proportions of Black patients, some programs have also perpetuated structural racism. To try to build equity into payment models, CMS recently announced the Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Accountable Care Organization (ACO) model, which includes a higher benchmark for ACOs caring for socioeconomically disadvantaged patients. The model also requires ACOs to develop and implement health equity plans and collect patient-reported data on demographics and social determinants of health. The authors say it will be important to evaluate whether the benchmark adjustment is adequate and to see how widely this model is taken up. Suhas Gondi, Karen Joynt Maddox, and Rishi K. Wadhera, “REACHing” for Equity — Moving from Regressive toward Progressive Value-Based Payment,” New England Journal of Medicine, 387, no. 2 (July 2022):97–9.

Examining How Neighborhood Characteristics Relate to Pediatric Asthma Morbidity

This study looked at how characteristics of children’s neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. — including census-level measures of educational attainment, vacant housing, violent crime, limited English proficiency, and families living in poverty — relate to pediatric asthma morbidity. It looked at at-risk rates (ARRs), a measure of how many children with asthma within a specific geographic area had ED visits or hospitalizations. During the study period, 4,321 children had 7,515 encounters for asthma and 1,182 children had 1,588 hospitalizations. In adjusted analyses, decreased educational attainment was significantly associated with ARRs of ED visits and hospitalizations. Violent crime was significantly associated with ARRs for ED visits. The researchers conclude that place-based interventions focused on the social determinants of health may be an opportunity to reduce pediatric asthma morbidity. Jordan Tyris et al., “Social Determinants of Health and At-Risk Rates for Pediatric Asthma Morbidity,” Pediatrics (2022) 150 (2):e2021055570.

Special thanks to Editorial Advisory Board member Allison Hamblin for her help with this issue.

Jean Accius, Ph.D., senior vice president, AARP

Anne-Marie J. Audet, M.D., M.Sc., senior medical officer, The Quality Institute, United Hospital Fund

Eric Coleman, M.D., M.P.H., director, Care Transitions Program

Marshall Chin, M.D., M.P.H., professor of healthcare ethics, University of Chicago

Timothy Ferris, M.D., M.P.H., National Director of Transformation, NHS England

Don Goldmann, M.D., chief medical and scientific officer, Institute for Healthcare Improvement

Laura Gottlieb, M.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of family and community medicine, University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

Carole Roan Gresenz, Ph.D., senior economist, RAND Corp.

Allison Hamblin, M.S.P.H., president and chief executive officer, Center for Health Care Strategies

Thomas Hartman, vice president, IPRO

Sinsi Hernández-Cancio, J.D., vice president for health justice, National Partnership for Women & Families

Clemens Hong, M.D., M.P.H., medical director of community health improvement, Los Angeles County Department of Health Services

Kathleen Nolan, M.P.H., regional vice president, Health Management Associates

Harold Pincus, M.D., professor of psychiatry, Columbia University

Chris Queram, M.A., president and CEO, Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality

Sara Rosenbaum, J.D., professor of health policy, George Washington University

Michael Rothman, Dr.P.H., executive director, Center for Care Innovations

Mark A. Zezza, Ph.D., director of policy and research, New York State Health Foundation

Publication Details

Date

Citation

Martha Hostetter and Sarah Klein, How Health Care Organizations Are Preparing for Climate Shocks and Protecting Vulnerable Patients (Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 20, 2022). https://doi.org/10.26099/486j-w130

Area of Focus