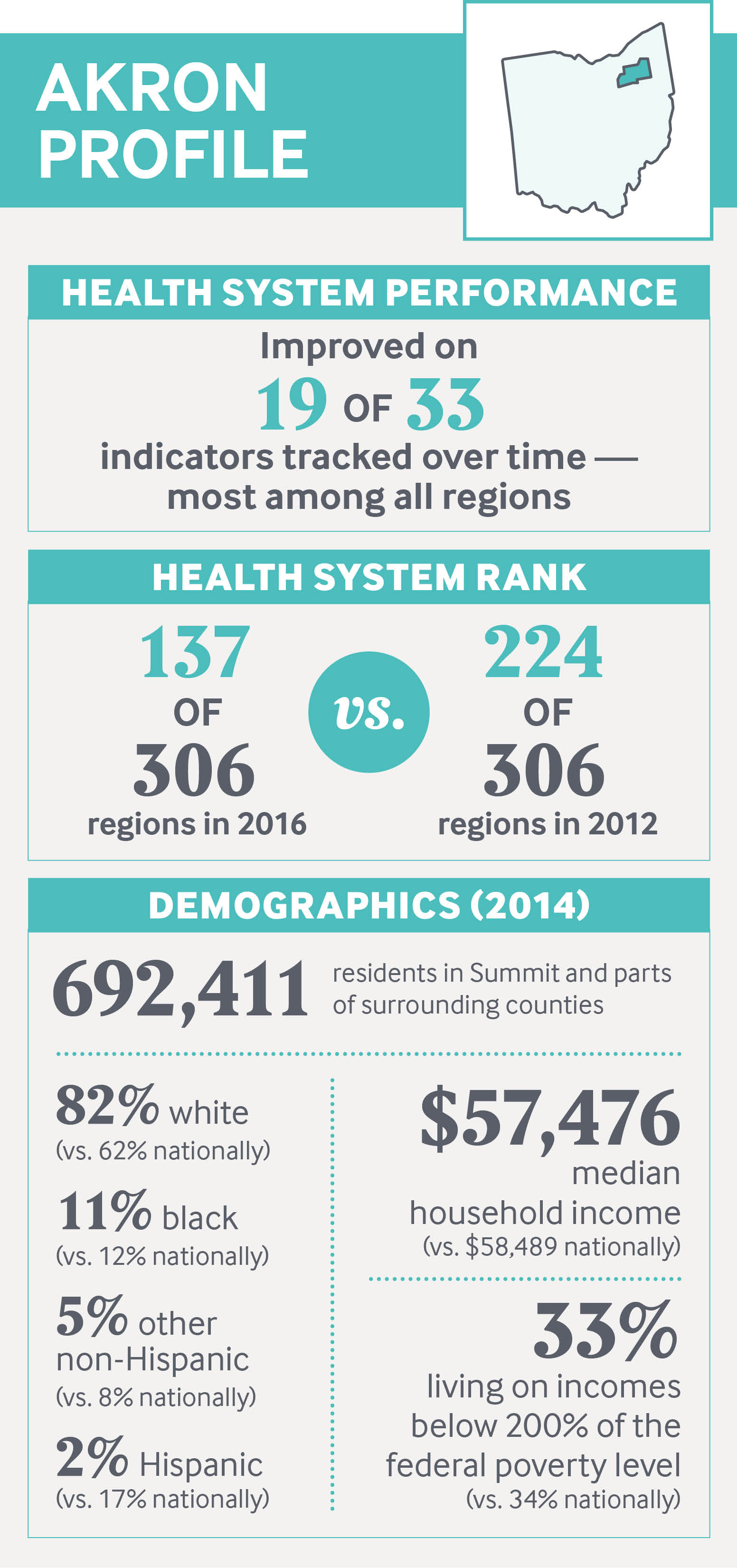

The Northeast Ohio region centered on the city of Akron and Summit County as well as parts of nearby counties stands out, along with Stockton, Calif., for having improved on more performance measures (19 of 33) than any other region on the Commonwealth Fund’s Scorecard on Local Health System Performance, 2016 Edition. The region has made notable progress expanding access to care. Health systems also have strengthened primary care and improved care transitions, which may explain reductions in potentially avoidable hospitalizations and unplanned readmissions. Collaboration across health and social service sectors is a hallmark of the region, exemplified by use of a shared set of measures assessing residents’ quality of life. But to address deep-seated problems, such as the high black infant mortality rate, leaders say the region also will need to make specific commitments and potentially reallocate resources to see improvement.

Background

With just under 200,000 residents, the Northeastern Ohio city of Akron in Summit County is often described as a big small town. Civic and business leaders say they see familiar faces as they move between workplaces or committees and prize residents’ warmth and lack of pretension, which some attribute to the city’s blue-collar roots. Once known as the “Rubber Capitol of the World,” Akron had a thriving rubber industry for much of the 20th century. In 1950 it produced one of every three tires on American roads, but during the late twentieth century it lost many manufacturing jobs and with them roughly a third of its population.1 Since then, “meds and eds” have anchored the economy, with Summa Health, Akron General, and the Akron Children’s health systems and the University of Akron all major employers. In recent years the region has had some success in repurposing its industrial equipment and workforce into polymer and other advanced manufacturing, thus staking its future on the strongest parts of its past.2

Akron’s residential neighborhoods still have strong ethnic identities (including the rubber company–built Firestone Park and Goodyear Heights). A highway running through downtown also has reinforced neighborhood boundaries and in some cases created pockets of poverty and isolation. Despite these divisions, leaders say residents have shown a willingness to help one another. “What we have here is a rich mix of individuals and businesses and government that come together to solve community problems,” says Donna Skoda, health commissioner of Summit County Public Health.

This case study is part of a series exploring the factors that may contribute to improved regional health system performance. It describes initiatives led by the public health department, local government, and other partners to promote healthy behaviors and build a healthier environment, as well as those led by health systems and other providers to improve services, particularly for those most at risk. Akron’s progress is noteworthy; while its poverty rate is not as high as other regions examined in our series, it nonetheless faces pressing health problems common to other “rust belt” cities, including high rates of obesity and other chronic conditions, a persistently high infant mortality rate among African Americans, and an epidemic of opioid addiction.3

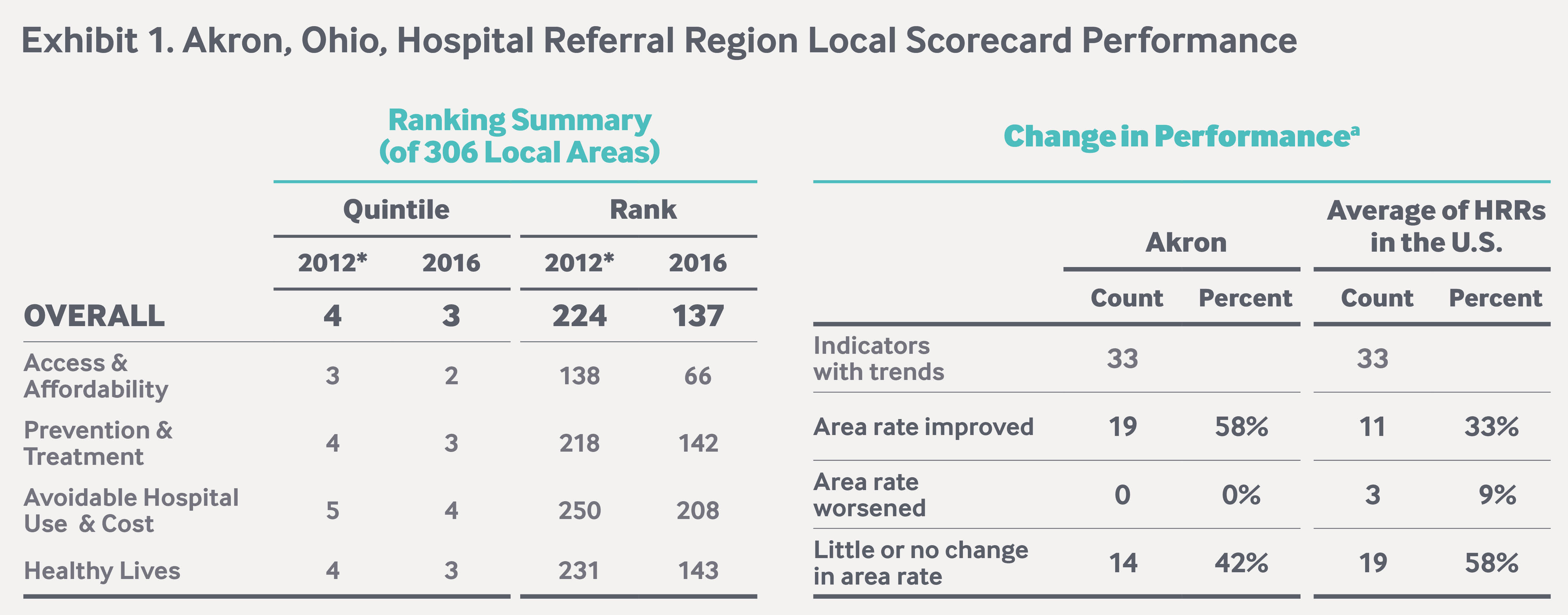

Health System Performance in Akron

Akron is one of 306 hospital referral regions, or regional markets for health care, in the United States. The area includes the city of Akron and surrounding Summit County as well as parts of nearby counties. On the Commonwealth Fund’s Scorecard on Local Health System Performance, 2016 Edition, the region, along with Stockton, Calif., stands out for having improved on more performance measures (19 of 33) than any other region (Exhibit 1). In comparing the performance of U.S. hospital referral regions, the Scorecard found wide variation on indicators of health care access, quality, avoidable hospital use, costs, and outcomes.

Data: D. C. Radley, D. McCarthy, and S. L. Hayes, Rising to the Challenge: The Commonwealth Fund Scorecard on Local Health System Performance, 2016 Edition, The Commonwealth Fund, July 2016.

Expanding Access and Improving Care

The Akron region has made significant progress expanding access to care, thanks to efforts by local health systems to enroll residents in Ohio’s expanded Medicaid program or in subsidized coverage through the federal health insurance marketplace. The Scorecard found that from 2012 to 2014, the uninsured rate among working-age adults dropped from 16 percent to 10 percent, compared with national figures of 21 percent and 16 percent, respectively. Perhaps as a result of expanded coverage, more adults said they actually sought out services, and more received recommended vaccinations.

Akron also has made progress in reducing unplanned hospital readmissions after years of effort to promote safe transitions between hospitals and community settings, led by Direction Home of Akron and Canton, the Area Agency on Aging (AAA). Since 1998, the AAA has embedded field coaches (either social workers or nurses) in local hospitals. The coaches talk with seniors soon after they’re admitted about their needs for rehabilitative services and other supports after discharge, such as home-delivered meals or transportation. The coaches focus in particular on addressing the “social determinants that may have caused people to go the hospital in the first place,” says Abigail Morgan, senior vice president of planning and quality improvement at Direction Home of Akron and Canton.

We have purposefully worked to develop relationships with all regional hospitals, even having their folks on our board so we can understand each other.Susan SigmonSenior Vice President, Managed Long-Term Care, Direction Home of Akron and Canton

The AAA was one of the first groups selected by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to lead a Community-Based Care Transitions program, an Affordable Care Act demonstration designed to encourage hospitals and community organizations to work together to reduce readmissions among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries through better discharge planning and other efforts. Together, the 10 participating hospitals reduced 30-day hospital readmissions from 19.6 percent in 2010 to 11.7 percent in September 2016 (compared with a national rate of 15.6 percent for the period July 2014 through June 2015).4

Area hospitals also are leading efforts to promote safe care transitions. Akron General, for instance, has reduced readmissions among patients recovering from total joint replacements by more closely collaborating with skilled nursing facilities and allowing community providers to use a HIPAA-compliant platform to securely text pictures of patients’ incisions to surgeons, who can help ensure they’re healing well. Hospital staff also have begun notifying primary care providers when their patients are discharged so that they can follow up with them by phone or in person.

Building Medical Homes

Despite this success in reducing readmissions, Scorecard data suggest Akron has work to do to reduce the number of people hospitalized in the first place. The region has relatively high rates of admissions among Medicare beneficiaries for conditions that can often be managed in ambulatory care settings, though there was some progress from 2012 to 2014. To strengthen the capacity of primary care providers to manage patients’ conditions, Akron’s health systems have been promoting patient-centered medical homes.5

For example, Summa Health, which serves 22,000 beneficiaries through a Medicare Shared Savings accountable care organization (ACO) and another 68,000 through other value-based contracts, has given grants and other support to its primary care clinics to help them expand access to care and build teams that can proactively manage care for their sickest patients. Forty-seven of the health system’s 85 affiliated clinics have earned the highest level of medical home recognition from the National Committee for Quality Assurance. Nearly all (94 percent) had earned incentive payments for use of electronic health records by 2015, and most employ nurse care managers to help patients manage their chronic conditions.6 Summa also funds an after-hours nurse triage line, so patients have options other than the emergency department when problems occur. These and other changes have been associated with fewer unplanned hospitalizations among Medicare ACO beneficiaries, as well as improvement on measures of primary and preventive care.7 The ACO has earned shared savings from Medicare for three years in a row — the only one of Ohio’s 11 ACOs to achieve this.8

Summa’s shift to population health management began a decade ago, when it started building its shared electronic health record, and is still ongoing, says Mark Terpylak, D.O., president of NewHealth Collaborative, Summa’s ACO. “This is a long runway: there are a lot of bricks to be laid, a lot of culture change that has to occur,” he says.

Collaboration Across Sectors to Reach Vulnerable Populations

Akron’s ability to convene community leaders from across sectors is partly a function of its small size and the sense of accountability this engenders. The region also has been blessed with leaders who’ve worked to unite people, including the recently deceased County Executive Russ Pry, who brought county agencies and city government together to tackle shared problems.

One example of the way the community has rallied around a cause is its work to reduce infant mortality. Starting in 2006, several public agencies “put every extra penny we ever had in this county to buy cribs,” says Skoda. Summit County now has very few infant deaths from cosleeping, though infant mortality rates are still high among African Americans, prompting further efforts as described below.

Several partners launched another collaborative effort to find creative approaches to help bring people out of poverty. Prompted by a local minister who saw the day-to-day struggles of the working poor, the partners secured United Way and state funding to offer free “Getting Ahead” workshops, which provide training in financial literacy and other life skills. The program has thus far been delivered to some 250 residents, including low-wage workers seeking guidance on how to earn promotions and develop their careers.

The public health department has been a leader in these and other cross-sector efforts to help vulnerable populations — a shift from its past role of offering services to one resident at a time. “We failed miserably with efforts like nutritional counseling,” says Skoda. “That 20 minutes of counseling doesn’t do a bit of good if people can’t buy fruits and vegetables.” Instead, in recent years the public health department has partnered with local government, schools, and others to create urban gardens and food hubs to bring more healthy eating options into urban neighborhoods. The partners also helped to create walking and biking paths to encourage exercise and use of nearby Cuyahoga National Park.

As Akron works to dismantle 30 acres of highway and redevelop the Ohio and Erie Canal towpath that runs through economically and racially diverse neighborhoods, a new vision of the downtown area is taking shape. To capitalize on this opportunity, the public health department is pushing city and county planners to consider the health impacts of their transportation and development plans through adoption of a “Health in All Policies” charter.

Using Data to Improve

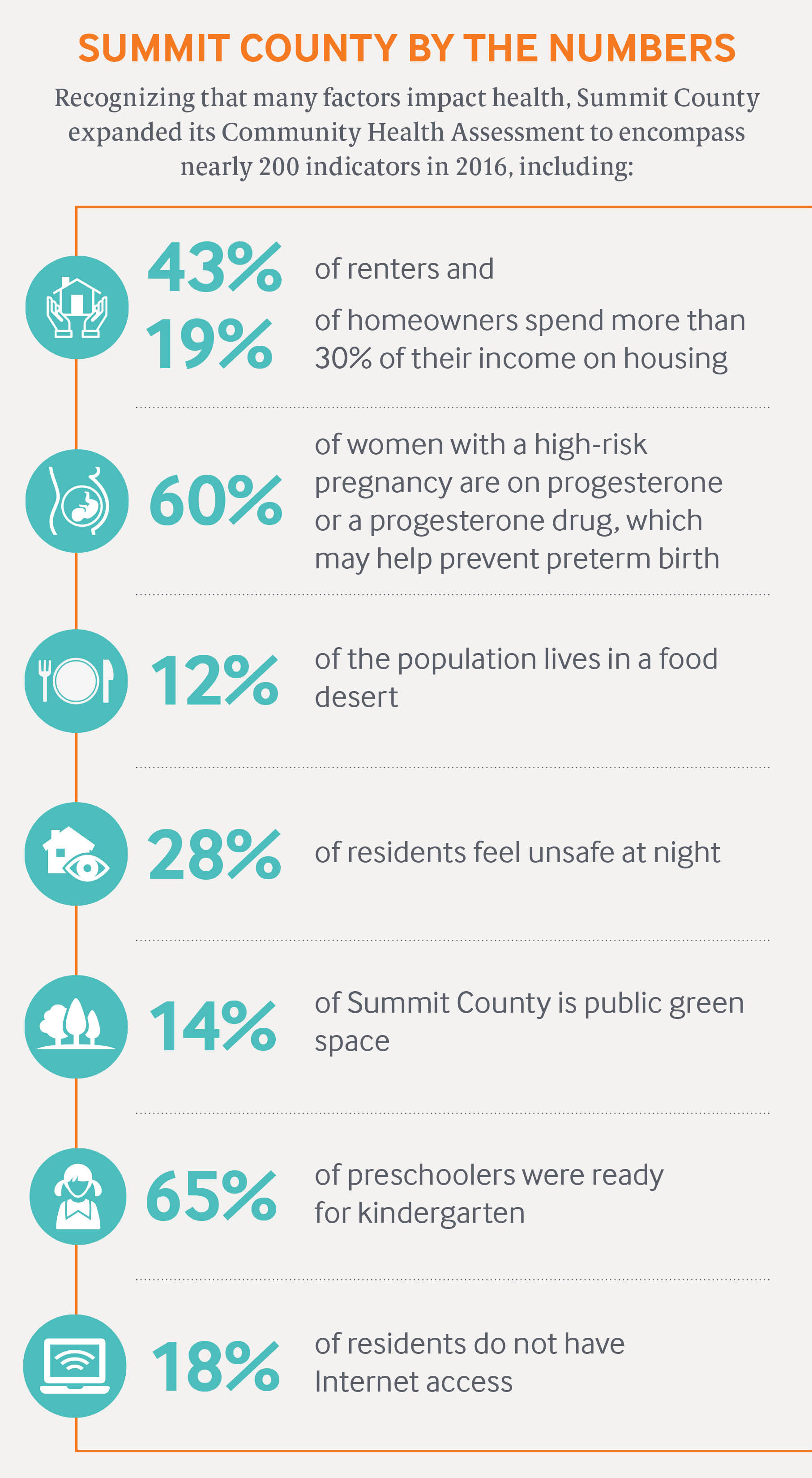

One of the threads running through such efforts is leaders’ willingness to be guided by data. This approach dates back to at least 2003, when the former Summit County Executive convinced leaders from the health, housing, transit, aging, and other social service agencies to pool their efforts to improve residents’ quality of life, relying on a shared set of indicators to measure progress. All parties to this cross-sector effort, now known as Summit 2020, must explain how their funds are being used to make progress on 17 indicators, which focus on morbidity and mortality as well as socioeconomic factors such as educational attainment, affordability of housing, and instances of violence, abuse, or neglect that can have an outsize impact on health.

Prior to having the software, if we wanted obesity rates, we either had to use a survey or driver’s license data. And how honest are people on their driver's license?Cory KendrickDirector of Population Health, Summit County Public Health

And for the most recent community health assessment, partners added several measures assessing residents’ social and economic well-being and examining how the built environment affects health — expanding from 29 indicators in 2011 to nearly 200 measures in 2016. Some new measures target identified problems. For example, in response to evidence that prematurity contributes to infant mortality in the region, a measure was added to track the number of women with high-risk pregnancies who receive progesterone, which can prevent preterm birth.

To inform this and other work, Summit County Public Health invested in the Explorys analytics platform, which enables it to gather and aggregate clinical data from area health systems in near–real time.

Summit County’s Alcohol, Drug Addiction, and Mental Health Services (ADM) Board, which funds some 25 behavioral health agencies, also has used data to improve services. In response to the region’s spiraling opioid abuse epidemic, ADM Board leaders created a dashboard to track opiate dispensing, wait times for addiction treatment, overdoses, and other key measures. This dashboard has enabled the board to be nimble in its responses. For example, when data showed that many overdose victims had never been in treatment, the ADM Board provided funding for a staff member from a local detox center to be on call 24/7, so that when an overdose victim arrives at a local emergency department the staffer can rush over to try instill hope and engage him or her in treatment. It also helped to create an ambulatory detox center for teens — one of the only such facilities in the nation — in response to evidence that addicts were increasingly younger and may do better in treatment settings with their peers.

Engaging Residents

Akron’s leaders also are working to engage residents in health improvement efforts. Akron’s mayor, Daniel Horrigan, has been using his office to rally people around the issue of health equity — an unusual topic for a mayor to champion.9 His initial focus is on securing a communitywide commitment to reduce the infant mortality rate among African American babies, which in 2015 was 14 per 1,000, compared with 5.7 per 1,000 among Hispanics and whites.10 While overall infant mortality rates have improved in recent years, black infant mortality rates remain the same as they were 100 years ago. Black babies are also more likely to be born prematurely, a leading cause of mortality: in 2015, 19 percent were born before 37 weeks gestation, compared with 12 percent of Hispanic and white babies.11

The Mayor’s Office and its partners have been engaging black residents and community leaders to brainstorm solutions. “We have to create momentum on the demand side,” says James Hardy, Akron’s deputy mayor for administration and chief of staff. “We have to have the community conversation about why this is important.” At a 2016 Health Equity Summit, 100 participants — including representatives from city, county, and state government, health providers, health plans, public health, local and national nonprofits, the housing and transit authorities, NAACP, universities, a church-led dads’ group, and several women who had been teenage mothers — came together to discuss the causes of black infant mortality and how they can work together to address them. Through discussion and real-time polling, the group identified first steps, including direct outreach and a public health campaign to educate pregnant women in high-risk neighborhoods about good prenatal care. “The data point to social factors that impact premature birth,” says Horrigan. “Physicians alone can’t fix this; we need every sector to get behind this issue. But somebody has to take the lead.”

Photos courtesy of City of Akron Mayor’s Office, Daniel Horrigan, Mayor.

Moving from Collaboration to Coordination

To make further progress in improving residents’ health, Akron’s leaders may need to more closely coordinate efforts across sectors, leaders say. “Collaboration and coordination are two different things,” says Hardy. Developing partnerships and good working relationships is a necessary foundation, he says, but coordination would entail specific commitments and if necessary reallocation of resources to address deep-seated problems that have multiple causes. This call for coordination — echoed by others — stems from recognition of mutual dependence; for example, Akron’s EMS handles drug overdoses but Summit County is charged with preventing them. And yet it can be challenging to coordinate efforts when money and jobs are at stake. “We have to move beyond the, ‘Okay yes we’re willing to sit at the table’ to ‘What are the action steps that we can hold ourselves accountable to? What can we measure to move that needle?’” says Terry Albanese, assistant to the mayor for education, health, and families.

Akron’s troubled “Accountable Care Community” (ACC) offers a cautionary tale of the difficulty of coordination, particularly in a region with fiercely competitive health systems. Formed in 2011 among local health systems, universities, and the public health department with a mission to reduce chronic disease, the group claimed some progress in an early diabetes management program. But the partnership faltered after a few years following the loss of a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), lack of cooperation among the competitive health systems, and some participants’ desire to focus on potentially income-generating biotech rather than population health.

Skoda says she and other community leaders learned something from this experience: “The legacy of the Accountable Care Community has been to sell the community on the CDC’s health impact pyramid — showing that you get the most bang for your buck in addressing socioeconomic factors and building environments that enable healthy decision-making.”

Lessons

Perseverance and humility can be important ingredients in the success of improvement efforts. Akron’s leaders have launched several different efforts to improve residents’ health, and not all have been successful. But leaders appear willing to learn from unsuccessful efforts and persevere — traits that research has demonstrated are characteristic of organizations that succeed.12

Counties can serve as a locus for change. Summit County’s public health department has served as a convener of health care providers, health plans, nonprofits, and others in efforts to improve residents’ health. It also has used these partnerships to inject considerations of health into discussions of the city’s built environment, education, transportation, and other issues. And county leaders have shown a willingness to use data to promote accountability and improve services.

State and federal policy and programs can play an important role supporting local health system improvements. The Akron region leveraged the state’s Medicaid expansion and use of the federal health insurance marketplace to dramatically expand access to care. Providers also have participated in state and federal efforts to improve care, gaining both financial support and guidance for their efforts.